The Los Angeles Culinary Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pet Or Food: Animals and Alimentary Taboos in Contemporary Children’S Literature

Beyond Philology No. 14/3, 2017 ISSN 1732-1220, eISSN 2451-1498 Pet or food: Animals and alimentary taboos in contemporary children’s literature JUSTYNA SAWICKA Received 8.07.2017, received in revised form 16.09.2017, accepted 21.09.2017. Abstract In books for pre-school and early school-age children (4-9 years of age) published in Poland between 2008 and 2014 it is possible to observe a new alimentary taboo. Though statistics show that we consume more meat than ever, we seem to be hiding this fact from the children. The animal is disconnected from the meat, which becomes just a thing we eat so that there is no need to consider animal suffering or to apply moral judgement to this aspect. The analysed books, written by Scandinavian, Spanish and American and Polish authors, do not belong to the mainstream of children’s literature, but, by obscuring the connection between the animal and the food we consume, they seem to testify to the problem with this aspect of our world that the adults – authors, educators and parents. Key words alimentary taboo, children’s literature, pre-school children, animal story, Scandinavian children’s literature 88 Beyond Philology 14/3 Uroczy przyjaciel czy składnik diety: Tabu pokarmowe we współczesnych książkach dla dzieci Abstrakt Książki dla dzieci w wieku przedszkolnym i wczesnoszkolnym (4-9 lat) wydane w Polsce w latach 2008-2014 są świadectwem istnienia nowego tabu pokarmowego. Chociaż statystyki wskazują, że obecnie jemy więcej mięsa niż kiedykolwiek wcześniej, coraz częściej ukrywamy przed dziećmi fakt zjadania zwierząt. Odzwierzęcamy mięso i czynimy je przedmiotem, wtedy bowiem nie musimy zasta- nawiać się nad cierpieniem zwierząt i nad moralnym osądem tego faktu. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

National Journalism Awards

George Pennacchio Carol Burnett Michael Connelly The Luminary The Legend Award The Distinguished Award Storyteller Award 2018 ELEVENTH ANNUAL Jonathan Gold The Impact Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB CBS IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY CAROL BURNETT. YOUR GROUNDBREAKING CAREER, AND YOUR INIMITABLE HUMOR, TALENT AND VERSATILITY, HAVE ENTERTAINED GENERATIONS. YOU ARE AN AMERICAN ICON. ©2018 CBS Corporation Burnett2.indd 1 11/27/18 2:08 PM 11TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards Los Angeles Press Club Awards for Editorial Excellence in A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 2017 and 2018, Honorary Awards for 2018 6464 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 870 Los Angeles, California 90028 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (310) 464-3577 E-mail: [email protected] Carper Du;mage Website: www.lapressclub.org Marie Astrid Gonzalez Beowulf Sheehan Photography Beowulf PRESS CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT: Chris Palmeri, Bureau Chief, Bloomberg News VICE PRESIDENT: Cher Calvin, Anchor/ Reporter, KTLA, Los Angeles TREASURER: Doug Kriegel, The Impact Award The Luminary The TV Reporter For Journalism that Award Distinguished SECRETARY: Adam J. Rose, Senior Editorial Makes a Difference For Career Storyteller Producer, CBS Interactive JONATHAN Achievement Award EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus GOLD International Journalist GEORGE For Excellence in Introduced by PENNACCHIO Storytelling Outside of BOARD MEMBERS Peter Meehan Introduced by Journalism Joe Bell Bruno, Freelance Journalist Jeff Ross MICHAEL Gerri Shaftel Constant, CBS CONNELLY CBS Deepa Fernandes, Public Radio International Introduced by Mariel Garza, Los Angeles Times Titus Welliver Peggy Holter, Independent TV Producer Antonio Martin, EFE The Legend Award Claudia Oberst, International Journalist Lisa Richwine, Reuters For Lifetime Achievement and IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY Ina von Ber, US Press Agency Contributions to Society CAROL BURNETT. -

FCC Quarterly Programming Report Jan 1-March 31, 2017 KPCC-KUOR

Southern California Public Radio- FCC Quarterly Programming Report Jan 1-March 31, 2017 KPCC-KUOR-KJAI-KVLA START TIME Duration min:sec Public Affairs Issue 1 Public Affairs Issue 2 Show & Narrative 1/2/2017 TAKE TWO: The Binge– 2016 was a terrible year - except for all the awesome new content that was Entertainment Industry available to stream. Mark Jordan Legan goes through the best that 2016 had to 9:42 8:30 offer with Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: The Ride 2017– 2017 is here and our motor critic, Sue Carpenter, Transportation puts on her prognosticator hat to predict some of the automotive stories we'll be talking about in the new year 9:51 6:00 with Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: Presidents and the Press– Presidential historian Barbara Perry says contention between a President Politics Media and the news media is nothing new. She talks with Alex Cohen about her advice for journalists covering the 10:07 10:30 Trump White House. TAKE TWO: The Wall– Political scientist Peter Andreas says building Trump's Immigration Politics wall might be easier than one thinks because hundreds of miles of the border are already lined with barriers. 10:18 12:30 He joins Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: Prison Podcast– A podcast Law & is being produced out of San Quentin Media Order/Courts/Police State Prison called Ear Hustle. We hear some excerpts and A Martinez talks to 10:22 9:30 one of the producers, Nigel Poor. TAKE TWO: The Distance Between Us– Reyna Grande grew up in poverty in Books/ Literature/ Iguala, Mexico, left behind by her Immigration Authors parents who had gone north looking for a better life and she's written a memoir for young readers. -

A Little Book of Soups: 50 Favourite Recipes Free

FREE A LITTLE BOOK OF SOUPS: 50 FAVOURITE RECIPES PDF New Covent Garden Soup Company | 64 pages | 01 Feb 2016 | Pan MacMillan | 9780752265766 | English | London, United Kingdom A Little Book of Soups by New Covent Garden Soup Company | Waterstones Unfortunately we are currently unable to provide combined shipping rates. It has a LDPE 04 logo on it, which means that it can be recycled with other soft plastic such as carrier bags. We encourage you to recycle the packaging from your World of Books purchase. If ordering within the UK please allow the maximum 10 business days before contacting us with regards to delivery, once this has passed please get in touch with us so that we can help you. We are committed to ensuring each customer is entirely satisfied with their puchase and our service. If you have any issues or concerns please contact our customer service team and they will be more than happy to help. World of Books Ltd was founded inrecycling books sold to us through charities either directly or indirectly. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. We now ship over two million orders each year to satisfied customers throughout the world and take great pride in our prompt delivery, first class customer service and excellent feedback. While we do our best to provide good quality books A Little Book of Soups: 50 Favourite Recipes you to read, there is no escaping the fact that it has been owned and read by someone else before you. -

2020 Annual Recipe SIP.Pdf

SPECIAL COLLECTOR’SEDITION 2020 ANNUAL Every Recipe from a Full Year of America’s Most Trusted Food Magazine CooksIllustrated.com $12.95 U.S. & $14.95 CANADA Cranberry Curd Tart Display until February 22, 2021 2020 ANNUAL 2 Chicken Schnitzel 38 A Smarter Way to Pan-Sear 74 Why and How to Grill Stone 4 Malaysian Chicken Satay Shrimp Fruit 6 All-Purpose Grilled Chicken 40 Fried Calamari 76 Consider Celery Root Breasts 42 How to Make Chana Masala 77 Roasted Carrots, No Oven 7 Poulet au Vinaigre 44 Farro and Broccoli Rabe Required 8 In Defense of Turkey Gratin 78 Braised Red Cabbage Burgers 45 Chinese Stir-Fried Tomatoes 79 Spanish Migas 10 The Best Turkey You’ll and Eggs 80 How to Make Crumpets Ever Eat 46 Everyday Lentil Dal 82 A Fresh Look at Crepes 13 Mastering Beef Wellington 48 Cast Iron Pan Pizza 84 Yeasted Doughnuts 16 The Easiest, Cleanest Way 50 The Silkiest Risotto 87 Lahmajun to Sear Steak 52 Congee 90 Getting Started with 18 Smashed Burgers 54 Coconut Rice Two Ways Sourdough Starter 20 A Case for Grilled Short Ribs 56 Occasion-Worthy Rice 92 Oatmeal Dinner Rolls 22 The Science of Stir-Frying 58 Angel Hair Done Right 94 Homemade Mayo That in a Wok 59 The Fastest Fresh Tomato Keeps 24 Sizzling Vietnamese Crepes Sauce 96 Brewing the Best Iced Tea 26 The Original Vindaloo 60 Dan Dan Mian 98 Our Favorite Holiday 28 Fixing Glazed Pork Chops 62 No-Fear Artichokes Cookies 30 Lion’s Head Meatballs 64 Hummus, Elevated 101 Pouding Chômeur 32 Moroccan Fish Tagine 66 Real Greek Salad 102 Next-Level Yellow Sheet Cake 34 Broiled Spice-Rubbed 68 Salade Lyonnaise Snapper 104 French Almond–Browned 70 Showstopper Melon Salads 35 Why You Should Butter- Butter Cakes 72 Celebrate Spring with Pea Baste Fish 106 Buttermilk Panna Cotta Salad 36 The World’s Greatest Tuna 108 The Queen of Tarts 73 Don’t Forget Broccoli Sandwich 110 DIY Recipes America’s Test Kitchen has been teaching home cooks how to be successful in the kitchen since 1993. -

12Th National A&E Journalism Awards

Ben Mankiewicz Tarana Burke Danny Trejo Quentin Tarantino The Luminary The Impact Award The Visionary The Distinguished Award Award Storyteller Award 2019 TWELFTH ANNUAL Ann-Margret The Legend Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB 12TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards A Letter From the Press Club President Good evening and welcome to the 12th annual National Arts & Entertain- ment Journalism Awards. Think about how much the entertainment industry has changed since the Press Club introduced these awards in 2008. Arnold Schwarzenegger was our governor, not a Terminator. Netflix sent you DVDs in the mail. The iPhone was one year old. Fast forward to today and the explosion of technology and content that is changing our lives and keeping journalists busy across the globe. Entertainment journalism has changed as well, with all of us taking a much harder look at how societal issues influence Hollywood, from workplace equality and diversity to coverage of political events, the impact of social media and U.S.-China rela- tions. Your Press Club has thrived amid all this. Participation is way up, with more Chris Palmeri than 600 dues-paying members. The National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards have grown and changed as well. Tonight we’re in a ballroom in the Millennium Biltmore Hotel, but in 2008 the awards took place in the Steve Allen Theater, the Press Club’s old home in East Hollywood. That building has since been torn down. Our first event in 2008 featured a cocktail party with no host and only 111 entries in the competition. -

Biotechnology-Inspired Solutions to Further Increase Sustainability and Healthiness in the Bakery Market

Biotechnology-Inspired Solutions to Further Increase Sustainability and Healthiness in the Bakery Market Joke A. Putseys1 DSM Food Specialties/DSM Biotechnology Center, Delft, The Netherlands products in sectors such as food, feed, and fuels. In doing so, it ABSTRACT uses renewable raw materials, making it one of the most inno- Biotechnology makes use of living organisms for the production of vative approaches to developing a circular, biobased economy. sustainable, biobased food, feed, fuel, and materials. Biocatalyst en- Many biotechnology-inspired solutions, such as enzymes, have zymes, used to improve the process or product quality of food, are a key already been developed to minimize food losses using low-car- example of how industrial biotechnology can be used to help address bon emission technologies. In addition to the functional ben- climate change and resource scarcity. In the bakery market and along efits enzymes can provide, the same technologies are applied in the baking value chain, various biotechnology-inspired solutions have the development of new products for growing markets, like or- already been implemented to reduce the carbon footprint by reduc- ganic and healthier bakery products. An overview of the general ing food waste and loss, lowering energy consumption, and creating benefits is provided in Figure 1. These benefits are listed Table I clean(er)-label products. Some challenges still remain, especially in realizing sustainable solutions for growing market trends, like healthier together with the problems they can be used to solve and poten- or organic baked products. tial feasible biotechnology-inspired solutions. Each of these top- ics will be discussed in more detail, with a focus on if and how each of these trends affects sustainability along the value chain. -

Soup Bagels Almonds

Jan/Feb/Mar 2021 The English Language Food Magazine For Portugal Lovers Everywhere SOUP BAGELS ALMONDS DO YOU SPEAK +++ T HE CHARM AND HISTORY OF CHOCOLATE?? BEAUTIFUL BOYFRIEND SCARVES TABLE OF CONTENTS IN EVERY ISSUE FEATURES 10 Wine Vines Food For Thought Black Sheep Lisboa/ 7 RealPortugueseWine.com Lucy Pepper, Eat Portugal 13 Not From Around Here Av’s Pastries & Catering The Secret Ingredient Is Always Chocolate 21 15 Let’s Talk Chocolate Master PracticePortuguese.com Pedro Martins Araújo, Vinte Vinte Chocolate 17 My Town Dylan Herholdt, Portugal Soup’s On: the Simple Life Podcast/ The Definitive Guide To 28 Portugal Realty Portugal’s Soup Scene 19 Portuguese Makers Amass. Cook. Lenços dos Namorados/ Aliança Artesanal Product Spotlight 38 52 Perspective Portuguese Rice David Johnson Guest Artist The Legend of the 12 41 Eileen McDonough, Almond Blossom Lisbon Mosaic Studio AB Villa Rentals Fado: The Sonority 43 Of Lisbon getLISBON Reader Recipe 45 Vivian Owens >>> Turn to pages 48-50 for Contributors/Recipe List/What’s Playing in Your Kitchen<<< FROM MY COZINHA The local food and flavor magazine for I don’t know about you, but these last several months I’ve been doing a lot of English-speaking Portugal traveling…in my mind. I catch myself lovers everywhere! staring into space, daydreaming, reliving some of my excellent adventures and planning an extensive Relish Portugal is published four multi-country train excursion across times a year plus two special Europe. I see friends on Zoom and, in editions. reality, my outside exploits are no more exotic than a trip to the grocery store or All rights reserved. -

20150511 ENG Report OVAM Food Loss and Packaging

Food loss and packaging Food loss and packaging Document description 1. Title of publication Food loss and packaging 2. Responsible Publisher 6. Number of pages Danny Wille, OVAM, Stationsstraat 110, 2800 Mechelen 3. Legal deposit number 7. Number of tables and figures 4. Key words 8. Date of publication Food, packaging, materials 5. Summary 9. Price* In 2013-2014 Studio Spark, VITO en Pack4Food did research, commissioned by OVAM, on the relationship between food waste and packaging. This was done in close collaboration with a Steering Committee representing different chain actors. Finally, a communication strategy was presented. 10. Steering committee and/or author Willy Sarlee, Joke Van Cuyk, Miranda Geusens (OVAM), Gaëlle Janssens (Fost Plus), Caroline Auriel (IVCIE), Kris Roels (Departement Landbouw en Visserij), Liesje De Schamphelaire (Fevia Vlaanderen), Geraldine Verwilghen (COMEOS) 11. Contact person(s) Willy Sarlee, OVAM, Unit Policy Innovation, 015 284 298, [email protected] Gaëlle Janssens, Fost Plus, 2 775 05 68, [email protected] 12. Other publications about the same subject Voedselverlies in ketenperspectief : OVAM, 2012 Verzameling van kwantitatieve gegevens van organisch-biologisch afval horeca. Mechelen : OVAM, 2012. Nulmeting van voedselverspilling bij Vlaamse gezinnen via sorteeranalyse van het restafval. Mechelen : OVAM, 2011 Voedselverspilling: literatuurstudie. Mechelen : OVAM, 2011. Information from this document may be reproduced with due acknowledgement of the source. Most OVAM publications can be -

THE PERUVIAN CHINESE COMMUNITY Isabelle Lausent-Herrera

b1751 After Migration and Religious Affiliation: Religions, Chinese Identities and Transnational Networks 8 BETWEEN CATHOLICISM AND EVANGELISM: THE PERUVIAN CHINESE COMMUNITY Isabelle Lausent-Herrera First Conversions to Catholicism Acuam1 must have been between 9 and 14 years old2 when he by Dr. Isabelle Lausent-Herrera on 09/04/14. For personal use only. debarked in Peru in 1850 from one of the first ships bringing in After Migration and Religious Affiliation Downloaded from www.worldscientific.com 1 The existence of this boy is known thanks to a document written in 1851 by José Sevilla, associate of Domingo Elías (Lausent-Herrera, 2006: 289). In the report “Representación de la Empresa a la Honorable Cámara de Senadores. Colonos Chinos”, Biblioteca Nacional de Lima (BNL), Miscelanea Zegarra, XZ-V58-1851, folio 37-38, José Sevilla tried to convince the Peruvian Government that the arrival in Peru of a great number of Chinese coolies was a good idea. For this, he reproduced the letters of satisfaction sent to him by all the hacendados, 185 bb1751_Ch-08.indd1751_Ch-08.indd 118585 224-07-20144-07-2014 111:10:101:10:10 b1751 After Migration and Religious Affiliation: Religions, Chinese Identities and Transnational Networks 186 After Migration and Religious Affiliation coolies for the great2sugar haciendas, the cotton plantations and the extraction of guano on the Chincha Islands. Since the year before, Domingo Elias and José Sevilla had started to import this new work- force destined for the hacendados to replace the Afro-Peruvians freed from slavery. Aiming to have a law voted to legalize this traffic between China and Peru, José Sevilla published a report investigat- ing the satisfaction of the first buyers. -

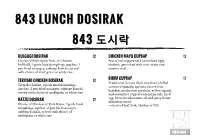

843 Lunch Dosirak

843843 LUNCHLUNCH DOSIRAKDOSIRAK 843843 도시락도시락 BULGOGI DOSIRAK 12 CHICKEN MAYO CUPBAP 12 Choice of Beef, Spicy Pork, or Chicken Bed of rice topped with scrambled eggs, BulGoGI, 2 pork fried dumplings, japchae, 2 chicken, garnished with nori, mayo and pan fried sausages, cabbage kimchi, served sesame seed. with choice of multigrain or white rice BIBIM CUPBAP 12 TERIYAKI CHICKEN DOSIRAK 12 Traditional Korean Style rice bowl, chilled Teriyaki chicken, 2 pork fried dumplings, seasoned spinach, sprouts, carrot, fern japchae, 2 pan fried sausages, cabbage kimchi, bracken, mushroom zucchini, yellow squash, served with choice of multigrain or white rice and cucumber topped with sunny side fried egg. Served with sesame oil and spicy house KATZU DOSIRAK 12 BiBimBap sauce. Choice of Chicken or Pork Katzu, 2 pork fried – choice of Beef, Pork, Chicken, or Tofu dumplings, japchae, 2 pan fried sausages, cabbage kimchi, served with choice of multigrain or white rice ããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããã"843" Happy Hour Tuesday - Saturday 3pm to 7pm, Excluding Holidays ALL DRAUGHT BEER $1 OFF Domestic Beer by Bottle $2 Angry Orchard, Bud Light, Bud Light Lime, Bud Light Orange, Budweiser, Coors Light, Michelob Ultra, Miller Lite, Sam Adams, Yuengling, Blue Moon Import Beer $3 Lucky Buddha, Asahi, Kirin Ichiban, Tiger, Chang, Stella Artois, Heineken Guinness,