Kathleen Johnson's Interview with Glenn Rupp of Ohio, 4-27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Roosevelt and the Supreme Court Bill of 1937

President Roosevelt and the Supreme Court bill of 1937 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hoffman, Ralph Nicholas, 1930- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 09:02:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319079 PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT AND THE SUPREME COURT BILL OF 1937 by Ralph Nicholas Hoffman, Jr. A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of History and Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1954 This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the Library to be made avail able to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without spec ial permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other in stances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: TABLE.' OF.GOWTENTS Chapter / . Page Ic PHEYIOUS CHALLENGES TO THE JODlClMXo , V . -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

Ch 15 the NEW DEAL

Ch 15 THE NEW DEAL AMERICA GETS BACK TO WORK SECTION 1: A NEW DEAL FIGHTS THE DEPRESSION I. Americans Get a New Deal A. The 1932 presidential election show Americans ready for change 1. Republicans re- nominated Hoover despite his low approval rating 2. The Democrats nominated Franklin D Roosevelt Election of 1932 Roosevelt Hoover ROOSEVELT WINS OVERWHELMING VICTORY a. Democrat Roosevelt, known as FDR, was a 2- term governor of NY b. reform-minded; projects friendliness, confidence B. Democrats overwhelmingly win presidency, Senate, House • Greatest Democratic victory in 80 years FDR easily won the 1932 election Election of 1932 Roosevelt’s Strengths • http://www.history.com/topics/1930s/videos #franklin-roosevelts-easy-charm C. Roosevelt’s Background 1. Distant cousin of Theodore Roosevelt. Came from a wealthy New York family. 2. Wife Eleanor was a niece of Theodore Roosevelt. • Charming, persuasive. • ServeD as secretary of the navy anD New York governor. Franklin and Eleanor Franklin as a young man 3. Polio a. In 1921 Roosevelt caught polio, a crippling disease with no cure. b. Legs were paralyzed and he wore steel braces and a wheelchair later in life. Roosevelt in a wheelchair D. Inauguration (March 4, 1933) 20th Amendment =January 20, ratified Jan 23, 1933 1. Between the election and his inauguration, the Depression worsened. 2. High unemployment, more bank failures. Roosevelt Inaugural speech Roosevelt Inaugural speech "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself. Nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance." The New Deal • http://www.history.com/topics/1930s/videos #the-new-deal-how-does-it-affect-us-today E. -

"The New Deal of War"

"The New Deal of War" By Torbjlarn SirevAg University of Oslo Half a year beforeJapanese pilots bombed the United States into World War 11, in a June 1941 edition of Coronet magazine, a little known author added his voice to that of other critics of the policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt. There were basically only two New Deals, John Pritchard here retorted to those who were debating the many twists and turns of the administration's policies. As he saw it, there had been a visionary and planning-oriented first stage-a "New Deal I" -from 1933 to the Nazi push into Holland in May 1940. Roughly at that time, however, the first stage had given way to a far more hardnosed phase which he labeled "New Deal I1- the New Deal of War." If Pritchard's phrase was new, the notion behind it was not. But his was and remains the most poignant expression of an attitude that for all its impact has never been fully understood. How can it be that even if a clear majority of the American people favored all steps short of war in the months immediately before Pearl Harbor the President hesitated to take the lead ?And how can it be explaineed that Washington remained in a state of political turmoil during most of the military emergency when other nations at this crucial moment set aside politics in a show of real national unity? In both situations, the corrosive influence of the "New Deal of War" idea remains crucial. In retrospect, this idea served the function as a bridge uniting the peacetime and wartime opposition against Roosevelt. -

CDIR-2018-10-29-VA.Pdf

276 Congressional Directory VIRGINIA VIRGINIA (Population 2010, 8,001,024) SENATORS MARK R. WARNER, Democrat, of Alexandria, VA; born in Indianapolis, IN, December 15, 1954; son of Robert and Marge Warner of Vernon, CT; education: B.A., political science, George Washington University, 1977; J.D., Harvard Law School, 1980; professional: Governor, Commonwealth of Virginia, 2002–06; chairman of the National Governor’s Association, 2004– 05; religion: Presbyterian; wife: Lisa Collis; children: Madison, Gillian, and Eliza; committees: Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Budget; Finance; Rules and Administration; Select Com- mittee on Intelligence; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2008; reelected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2014. Office Listings http://warner.senate.gov 475 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–2023 Chief of Staff.—Mike Harney. Legislative Director.—Elizabeth Falcone. Communications Director.—Rachel Cohen. Press Secretary.—Nelly Decker. Scheduler.—Andrea Friedhoff. 8000 Towers Crescent Drive, Suite 200, Vienna, VA 22182 ................................................... (703) 442–0670 FAX: 442–0408 180 West Main Street, Abingdon, VA 24210 ............................................................................ (276) 628–8158 FAX: 628–1036 101 West Main Street, Suite 7771, Norfolk, VA 23510 ........................................................... (757) 441–3079 FAX: 441–6250 919 East Main Street, Richmond, VA 23219 ........................................................................... -

Shoals Black History Educator Resource Packet

Shoals Black History Educator Resource Packet Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area Table of Contents Page 3: Introduction Page 4: Background Page 5: School Page 9: Religion Page 13: Work/Business Page 17: Community Page 18: Politics Page 25: People Page 29: Sports and Recreation Page 33: Music Page 37: Word Bank 2 Introduction This packet is the result of the Shoals Black History Project, a col- laborative effort between Project Say Something, the Florence- Lauderdale Public Library, and the University of North Alabama’s Pub- lic History Program. The Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area funded the project through their Community Grants Program. In the autumn of 2017, Project Say Something, in conjunction with the Florence- Lauderdale Public Library and students in the Public History program at UNA, hosted three history digitization events. At these events, com- munity members brought photographs, pamphlets, newspaper articles, documents, yearbooks, and other historical artifacts that were scanned and added to the public library’s online database. Volunteers also rec- orded oral histories at these events, and these recordings, along with typed transcripts, were added to the library’s database as well. This da- tabase can be accessed at: shoalsblackhistory.omeka.net. This effort seeks to incorporate African American history and life into the narrative of the Shoals area. In order for this history to be shared, it must first be gathered and organized; it can then be contextu- alized within national and regional trends and transformed into educa- tional resources that make sense of our common heritage and help us to better understand our present moment. -

Nicole Ives-Allison Phd Thesis

P STONES AND PROVOS: GROUP VIOLENCE IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND CHICAGO Nicole Dorothea Ives-Allison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/6925 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence P Stones and Provos: Group Violence in Northern Ireland and Chicago Nicole Dorothea Ives-Allison This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 20 February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Nicole Dorothea Ives-Allison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 83, 278 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2011 and as a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (International Relations) in May, 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2011 and 2014 (If you received assistance in writing from anyone other than your supervisor/s): I, Nicole Dorothea Ives-Allison, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of spelling and grammar, which was provided by Laurel Anne Ives-Allison. -

The Journey of FDR's Public Image As the Democratic Dictator

Northwest Passages Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 4 April 2014 The ourJ ney of FDR's Public Image as the Democratic Dictator Andrew Otton University of Portland Follow this and additional works at: http://pilotscholars.up.edu/nwpassages Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Otton, Andrew (2014) "The ourJ ney of FDR's Public Image as the Democratic Dictator," Northwest Passages: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: http://pilotscholars.up.edu/nwpassages/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Pilot Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwest Passages by an authorized administrator of Pilot Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Otton: The Journey of FDR's Public Image as the Democratic Dictator THE JOURNEY OF FDR’S PUBLIC IMAGE AS THE DEMOCRATIC DICTATOR n BY ANDREW W. OTTON ranklin Delano Roosevelt’s (FDR) public image rose in his first Fterm, fell in his second, and rebounded in his third. The essen- tial focus of this paper is to examine how FDR portrayed himself to the public, as well as explain the tumultuous nature of his image over his three terms. This is significant, as other scholarship has overlooked this important part, leaving the understanding of FDR lacking. Other scholarship focuses mostly on policy and politics when concerned with FDR’s speeches, specifically the fireside chats, and the potential societal, economic, cultural, etc. impact the speech might have had. Davis Houck is a good exception to that. He has a discussion of FDR trying to insert the traits of a dictator into his pub- lic image, which one will discuss later.1 Even when looking at rhetoricians, many spend their time discussing the particular way FDR used language to be effectively persuasive. -

Gaede to Be Law Alumni Association President

VOLUME 7 Contents 2 Editor's Column 3 Forum 4 Francois-Xavier Martin: Printer, Lawyer, Jurist/ Michael C. Chiorazzi 14 W7.ry the Candidates Still Use FDR as Their Measure/ William E. Leuchtenburg 25 Conference Report: Empirical Studies of Civil Procedure 27 About the School 28 A Perspective on Placement DEAN EDITOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Pamela B. Gann Evelyn M. Pursley Janse Conover Haywood NUMBER 1 35 The Docket 36 In the Public Interest 46 Alumna Profile: Pamela B. Gann 73 50 Book Review: 1999: Victory Without War by Richard M. Nixon '37 52 Specially Noted 56 Alumni Activities 64 Upcoming Events Duke Law Magazine is published under the auspices of the Office of the Dean, Duke University School of Law, Durham, North Carolina 27706 © Duke University 1989 BUSINESS MANAGER SUPPORT SERVICE PRODUCTION Mary Jane Flowers Evelyn Holt-Fuller Graphic Arts Services DUKE LAW MAGAZINE 12 Editor '5 Column The American legal world has pirical Studies of Civil Procedure article focuses on some our alumni changed greatly since the beginnings discusses the thought and efforts involved in such practice in a variety of our republic and continues to of some legal scholars who see em of ways and also reports on some change at a rapid rate. Though much pirical study as a method for effect law School programs designed to in the scene on our cover would ing possible changes in the legal encourage such interest. Our alum still be familiar in a modern law system. na proftle reports on our new dean, office (most lawyers I visit have The About the School section Pamela Gann '73. -

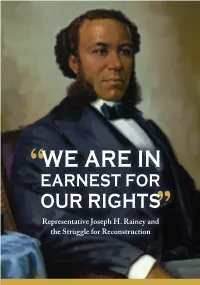

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

Exten,Sions O·F Remark.S Hon. Ralph Yarborough

February 16, 1970 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 3443 Aerographer James R. Dunlap George E. Meacham AMBASSADORS Joe E. McKinzie Morris E. Elsen Charles G. Morgan Jerome H. Holland, of Virginia, to be Am Clifford A. Froelich James D. Palmer bassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Photographer John W. Gebhart John W. Pounds, Jr. of the United States of America to Sweden. Kenneth R. Kimball William C. Griggs Ronald W. Robillard Robert Strausz-Hupe, of Pennsylvania, to Donald F. Sheehan Oran L. Houck Allen R. Shuff be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipo Joseph A. Hughes Kenneth M. St. Clair, tentiary of the United States of America to Civil Engineer Corps Paul B. Jacovelli Jr. Ceylon, and to serve concurrently and with Jerry G. Havner David H. Kellner Gerard R. Steiner out additional compensation as Ambassador Cecil W. Lovette, Jr. Marlene Marlitt Harold B. St. Peter Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Warrant Officer Edward G. Torres to be a *Michael T. Marsh Ronald J. Uzenoff United States of America to the Republic permanent chief warrant officer W-3 in the John A. Mattox Jerry E. Walton of Maldives. Joseph E. McClanahan Ervin B. Whitt, Jr. Navy in the classification of electrician, sub IN THE DIPLOMATIC AND FOREIGN SERVICE ject to the qualification therefor as provided James W. McHale William J . York Charles A. McPherronJohn A. Zetes The nominations beginning Keith E. Adam· by law. son, to be a Foreign Service information offi Warrant Officer Charles L. Boland, Jr., to •John A. Balikowski (civilian college gradu be a permanent chief warrant officer W-4 in ate) to be a permanent Lieutenant and a cer of class 1, and ending Harvey M. -

The Fusion of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian Thought in the Republican Party of the 1920S

© Copyright by Dan Ballentyne 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This work is dedicated to my grandfather, Raymond E. Hough, who support and nurturing from an early age made this work possible. Also to my wife, Patricia, whose love and support got me to the finish line. ii REPUBLICANISM RECAST: THE FUSION OF HAMILTONIAN AND JEFFERSONIAN THOUGHT IN THE REPUBLICAN PARTY OF THE 1920S BY Dan Ballentyne The current paradigm of dividing American political history into early and modern periods and organized based on "liberal" and "conservative" parties does not adequately explain the complexity of American politics and American political ideology. This structure has resulted of creating an artificial separation between the two periods and the reading backward of modern definitions of liberal and conservative back on the past. Doing so often results in obscuring means and ends as well as the true nature of political ideology in American history. Instead of two primary ideologies in American history, there are three: Hamiltonianism, Jeffersonianism, and Progressivism. The first two originated in the debates of the Early Republic and were the primary political division of the nineteenth century. Progressivism arose to deal with the new social problems resulting from industrialization and challenged the political and social order established resulting from the Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian debate. By 1920, Progressivism had become a major force in American politics, most recently in the Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson. In the light of this new political movement, that sought to use state power not to promote business, but to regulate it and provide social relief, conservative Hamiltonian Republicans increasingly began using Jeffersonian ideas and rhetoric in opposition to Progressive policy initiatives.