The Fusion of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian Thought in the Republican Party of the 1920S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Handbook

FACULTY HANDBOOK N E W Y O R K U N I V E R S I T Y A private University in the Public Service ARCHIVED PUBLISHED BY NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Issued April 2012 Table of Contents Introduction LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT ETHICAL COMMITMENT FOREWORD The University HISTORY AND TRADITIONS OF NEW YORK UNIVERSITY A Brief History of New York University University Traditions ORGANIZATION AND ADMINISTRATION The University Charter The Board of Trustees University Officers The University Senate University Councils and Commissions Organization of Schools, Colleges, and Departments LIBRARIES A Brief History Library Facilities and Services New York University Press UNIVERSITY RELATIONS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE FOR UNIVERSITY DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNI RELATIONS University Development Alumni Relations The Faculty ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND TENURE Title I: Statement in Regard to Academic Freedom and Tenure Title II: Appointment and Notification of Appointment Title III: Rules Regulating Proceedings to Terminate for Cause the Service of a Tenured Member of the Teaching Staff, Pursuant to Title I, Section VI, of the Statement in Regard to Academic Freedom and Tenure Title IV: General Disciplinary Regulations Applicable to Both Tenured and Non-Tenured Faculty Members OTHER FACULTY POLICIES Faculty Membership and Meetings Faculty Titles Responsibilities of the Faculty Member Compensation Sabbatical Leave Leave of Absence (paid and unpaid) Faculty Grievance Procedures Retirement University Benefits Legal Matters SELECTED UNIVERSITY RESOURCES FOR FACULTY Office of Faculty Resources -

~, Tt'tll\ E . a .. L Worilbl)Oc

"THE JOURNAL.OF ~, tt'tll\e ... A.. L WORilbl)oc ~.l)u AND Ok1 ERATORSJ.ljiru OFFICIAL PUBLICATION _.. INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF ElECTRICAL WORKER$--.- _ ~ -~- -' (:\ /~ //1 \"- II .0;,)[1 I October, 1920 !11AXADYI AFFILIATED WITH THE . AMERICAN 'FEDERATION OF LABOR IN ALL ITS D E PA R T M E.N T S II atLL II DEVOTED TO THE CAUSE OF ORGANIZED LABOR \ II 302~ "OUR FIXTURES ARE LIGHTING HOMES FROM COAST TO COAST" We have a dealer's proposition that will interest you. Our prices are low and quality of the best. Catalogue No. 18 free .ERIE FIXTURE SUPPLY CO. 359 West 18th St.. Erie. Pa. Blake Insulated Staples BLAKE 6 "3 . 4 Si;oel l Signal & Mfg. Co. n:t,· BOSTON :.: MASS. Pat. Nov. 1900 BLAKE TUBE FLUX Pat. July 1906 Tf T Convenient to carry and to use. Will not collect dust and dirt nor K'et on tools in kit. You can get the solder ina' Dux: just where YOD want it and in just tho desired Quantity. Named shoes are frequently made in non-union factories DO NOT BUY ANY SHOE No matter what its name, uniess it bears a plain and readable iinpression of the UNION STAMP All shoes without the UNION STAMP are always Non-Union Do not accept any excuse for absence of the UNION STAMP BOOT AND SHOE WORKERS' UNION II 246 Summer Street, Boston. Mass- I UCollis Lovely, General Pres. Charles L. Baine, General Sec.-Treall. , When 'writing mention The Journal of Electrical Workers and Operators. The Journal of Electrical Workers and Operators OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE International Brotherhood of Electrical Workera Affiliated with the American Federation of Labor and all Its DOepartments. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

Campaign and Transition Collection: 1928

HERBERT HOOVER PAPERS CAMPAIGN LITERATURE SERIES, 1925-1928 16 linear feet (31 manuscript boxes and 7 card boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library 151 Campaign Literature – General 152-156 Campaign Literature by Title 157-162 Press Releases Arranged Chronologically 163-164 Campaign Literature by Publisher 165-180 Press Releases Arranged by Subject 181-188 National Who’s Who Poll Box Contents 151 Campaign Literature – General California Elephant Campaign Feature Service Campaign Series 1928 (numerical index) Cartoons (2 folders, includes Satterfield) Clipsheets Editorial Digest Editorials Form Letters Highlights on Hoover Booklets Massachusetts Elephant Political Advertisements Political Features – NY State Republican Editorial Committee Posters Editorial Committee Progressive Magazine 1928 Republic Bulletin Republican Feature Service Republican National Committee Press Division pamphlets by Arch Kirchoffer Series. Previously Marked Women's Page Service Unpublished 152 Campaign Literature – Alphabetical by Title Abstract of Address by Robert L. Owen (oversize, brittle) Achievements and Public Services of Herbert Hoover Address of Acceptance by Charles Curtis Address of Acceptance by Herbert Hoover Address of John H. Bartlett (Herbert Hoover and the American Home), Oct 2, 1928 Address of Charles D., Dawes, Oct 22, 1928 Address by Simeon D. Fess, Dec 6, 1927 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Boston, Massachusetts, Oct 15, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Elizabethton, Tennessee. Oct 6, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – New York, New York, Oct 22, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Newark, New Jersey, Sep 17, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – St. Louis, Missouri, Nov 2, 1928 Address of W. M. Jardine, Oct. 4, 1928 Address of John L. McNabb, June 14, 1928 Address of U. -

Antitrust Status of Farmer Cooperatives

USDA Antitrust Status of Farmer Cooperatives: United States Department of Agriculture The Story of the Capper- Rural Business- Volstead Act Cooperative Service Cooperative Information Report 59 Abstract The Capper-Volstead Act provides a limited exemption from antitrust liability for agricultural producers who market the products they produce on a cooperative basis. Without Capper-Volstead, farmers who agree among themselves on the pric es they'll accept for their products and other terms of trade would risk being held in violation of antitrust law. Even with the exemption, agricultural producers are not free to unduly enhance the prices they charge, consolidate with or collaborate in anticompetitive conduct with nonproducers, or engage in conduct with no legitimate business purpose that is intended to reduce competition. Keywords: cooperative, antitrust, Capper-Volstead Act, law ________________________________________ Antitrust Status of Farmer Cooperatives: The Story of the Capper-Volstead Act Donald A. Frederick Program Leader Law, Policy & Governance Rural Business-Cooperative Service U.S. Department of Agriculture Cooperative Information Report 59 September 2002 RBS publications and information are available on the Internet. The RBS w eb site is: http://www.rurdev.usda.gov/rbs Preface Antitrust law poses a special challenge to agricultural marketing associations. Certain conduct by independent business people-- agreeing on prices, terms of sale, and whom to sell to--violates the Sherman Act and other antitrust statutes. And these are the very types of collaborative activities that agricultural producers conduct through their marketing cooperatives. Since 1922, the Capper-Volstead Act has provided a limited antitrust exemption for agricultural marketing associations. Producers, through qualifying associations, can agree on prices and other terms of sale, select the extent of their joint marketing activity, agree on common marketing practices with other cooperatives, and achieve substantial market share and influence. -

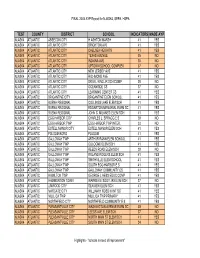

AYP 2003 Final Overall List

FINAL 2003 AYP Report for NJASK4, GEPA, HSPA TEST COUNTY DISTRICT SCHOOL INDICATORSMADE AYP NJASK4 ATLANTIC ABSECON CITY H ASHTON MARSH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY BRIGHTON AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY CHELSEA HEIGHTS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY TEXAS AVENUE 35 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY INDIANA AVE 35 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY UPTOWN SCHOOL COMPLEX 37 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY NEW JERSEY AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY RICHMOND AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY DR M L KING JR SCH COMP 38 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY OCEANSIDE CS 37 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY LEARNING CENTER CS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BRIGANTINE CITY BRIGANTINE ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL COLLINGS LAKE ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL EDGARTON MEMORIAL ELEM SC 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL JOHN C. MILANESI ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC EGG HARBOR CITY CHARLES L. SPRAGG E S 39 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC EGG HARBOR TWP EGG HARBOR TWP INTER. 33 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ESTELL MANOR CITY ESTELL MANOR ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC FOLSOM BORO FOLSOM 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP ARTHUR RANN ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP COLOGNE ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP REEDS ROAD ELEM SCH 39 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP ROLAND ROGERS ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP SMITHVILLE ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP SOUTH EGG HARBOR E S 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP. GALLOWAY COMMUNITY CS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State (#1-24)

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 9,10,13 Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams 14 William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson 18 Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe 5 John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams 12,13 John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren 7 Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison 21 Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk 6 Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor 15 Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce 1 John Jay 15 James Buchanan 19 William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson 7, 8 John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant 11 James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield 3 James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland 20,21,23James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison 10 John Calhoun 18 Elihu Washburne 1 Thomas Jefferson 22/24 Thomas Bayard 4 James Monroe 23 John Foster 2 John Marshall 16,17 William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 32 Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley 28 William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt 40 Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft 30 Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding 34 John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge 42 Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover 25 John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

"The New Deal of War"

"The New Deal of War" By Torbjlarn SirevAg University of Oslo Half a year beforeJapanese pilots bombed the United States into World War 11, in a June 1941 edition of Coronet magazine, a little known author added his voice to that of other critics of the policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt. There were basically only two New Deals, John Pritchard here retorted to those who were debating the many twists and turns of the administration's policies. As he saw it, there had been a visionary and planning-oriented first stage-a "New Deal I" -from 1933 to the Nazi push into Holland in May 1940. Roughly at that time, however, the first stage had given way to a far more hardnosed phase which he labeled "New Deal I1- the New Deal of War." If Pritchard's phrase was new, the notion behind it was not. But his was and remains the most poignant expression of an attitude that for all its impact has never been fully understood. How can it be that even if a clear majority of the American people favored all steps short of war in the months immediately before Pearl Harbor the President hesitated to take the lead ?And how can it be explaineed that Washington remained in a state of political turmoil during most of the military emergency when other nations at this crucial moment set aside politics in a show of real national unity? In both situations, the corrosive influence of the "New Deal of War" idea remains crucial. In retrospect, this idea served the function as a bridge uniting the peacetime and wartime opposition against Roosevelt. -

Mrs. Frank Knox Dies;

STAR LEGAL NOTICES PERSONAL THE EVENING (CONTINUED) (CONTINUtO) Washington, D. C. B-11I*s* SEPTEMBER M. your TUESDAY HHK.OK U. BIMHCH. «**•»», PIANOH—Wc «tor« tnd tell Knox Dies; Avenue N.W.. If lnt«r,»tfd in tbD rnnv Mrs. Frank 1601 Connecticut oltno Washington 6. 0. C. plan, writ, P 0 »«3 Etlv«r ! STAR CLASSIFIED LEADS SDrly ,Md _ UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the District of Columbia. Hold- NEAL VALIANT DANCE CLUB. ** ing 05 yr Mtmbcrihip limited. Wkly. or- the ether Washington papers by • Probate Court.—No. <26. Secretary Administration—Tbii Is to Oive chestra. record dtnce oartlen; In- PAY LESS Widow of oi . Notice: That the subscribers. Klruc etc. Per info. ME. the of New York and the deilre, healthy Statu Columbia, reipectlveb ELDERLY WIDOW MIAMI. Fla., Sept. 23 <AP'. District oi white lady under 7(1, or marrlrd have obtained from the Probat# couple Flor- GET MORE! —Mrs. Annie Reid Knox. 82. MILLIONS LINES Court of the District of Columbia, to «hare her home In OF. ida Room and in re- | on estate board free letter* teitamentary the companlomhlp rea- widow of former Secretary of of AONEB THERESA MARTIN, turn lor and j Frank Knox, died ¦ late of the District of Columbia, eonabie service» around houee. | Always the Navy deceased All person* having Call DAUOHTER. OL. 5-740 U, [ ust • home in sub- against deceased are alter «p m. yesterday at her claim* the _ ~ hereby warned to exhibit t)»u »unje, urban Coral Gables. tk- with the vouchers thereof, leaelly ENVELOPES ADDRESSED Fat authenticated, to the subscribers Real iate,. -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

1 Minutes of the N/C-Faculty Senators Council

Full-Time Non-Tenure Track/Contract Faculty Senators Council 194 Mercer Street, Suite 401 New York, NY 10012 P: 212 998 2230 F: 212 995 4575 [email protected] MINUTES OF THE N/C-FACULTY SENATORS COUNCIL MEETING OF FEBRUARY 12, 2015 The New York University Full-Time Non-Tenure Track/Contract Track Faculty Senators Council (N/C-FSC) met at noon on Thursday, September 11, 2014 in in the Global Center for Academic & Spiritual Life at 238 Thompson Street, 5th Floor Grand Hall. In attendance were Senators Becker, Borowiec, Burt (by phone), Caprio, Carl, Carter, Cittadino, Elcott, Fefferman, Gurrin, Halpin, Killilea, Mauro, Mooney, Morton, Mowry, Rainey, Slater, Stehlik, Stewart, Williams, and Youngerman; Alternate Senators Bianco, Casey, Cummings (for Sacks), Derrington, Lee, Renzi, and White. APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA Upon a motion duly made and seconded, the meeting agenda was approved unanimously. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD DECEMBER 4, 2015 Upon a motion duly made and seconded, the minutes of the December 4, 2015 meeting were approved with one abstention. REPORT FROM THE CHAIRPERSON: ANN MARIE MAURO Security Advisory Committee Chairperson Mauro reported the council was asked to nominate four members to the Security Advisory Committee. The N/C-FSC nominated Martha Caprio, Ralph Cunningham, Peggy Morton, and Andrew Williams. The Committee has representative categories concerning membership based on gender, school, and affiliation. Senators Morton, Williams, and Alternate Senator Cunningham were selected to serve on the Committee. Health Realignment Plan Discussion with Special Guest: Dr. Bob Berne, Executive Vice President for Health See attached Document B: Steering Committee with Bob Berne 1/8/15 and Health Realignment Materials.