Final Deposit Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV Movies and Series

TV movies and series 2006 Catalan Films & TV Televisió de Catalunya (TVC) Mestre Nicolau, 23, entresol Carrer de la TV3 s/n 08021 Barcelona 08970 Sant Joan Despí (Barcelona) Spain Tel.: + 34 935 524 940 Phone: + 34 935 674 967 Fax: + 34 935 524 953 Fax: + 34 934 731 563 E-mail: [email protected] Director: Àngela Bosch www.tvcatalunya.com Coordinators: Contact: Oriol Baquer Carme Puig - Int’l Department Mònica García - Marketing and Communication David Matamoros - Market Research and Coproductions Carme Romero - Administration Cata Massana - Assistant Director Printed by Ingoprint Dipòsit legal: TV MOVIES 18/9/06 10:12 Página 3 > GENERAL INDEX 3 > INTRODUCTION 4 > TV MOVIES AND SERIES 6 > IN DEVELOPMENT 60 > PRODUCTION & SALES COMPANIES 80 TV MOVIES 18/9/06 10:12 Página 4 THE PRODUCTION OF TV MOVIES HAS PROVED TO BE A FERTILE BREEDING GROUND FOR NEW TALENT, IN WHICH SCRIPTWRITERS, ACTORS, DIRECTORS AND PRO- DUCERS ALIKE PUT THEIR CREATIVE STRENGTHS TO THE TEST IN A GENRE CHARACTERIZED BY ITS IMMEDIACY AND FLEXIBILITY. The most remarkable aspect of TV movies is that they have embraced almost the full gambit of the- mes, though they have perhaps found their greatest area of growth in biopics and news or fact- based stories. This is the legacy the Catalan film and television industry took up very few years ago, and it has since gone on to create a burgeoning portfolio of TV movie titles. Over 50 titles have been broadcast in dedicated slots on Televisió de Catalunya, some involving new approaches to co-production. This catalogue brings together the most recent crop, conceived with a view to accessing all possible sales channels: theatrical release, theme channels, satellite, etc. -

STRENGTHENING PARENT and CHILD INTERACTIONS (13-18 Years)

STRENGTHENING PARENT AND CHILD INTERACTIONS (13-18 years) A Blue Dot indicates agencies that are a member of the Maternal Mental Health Collaborative and/or have attended the Postpartum Support International training. Being a parent can be very rewarding, but it can also be very challenging. Because your child is always growing, the information you need to know about parenting and child development changes constantly, too. Learning what behaviors are appropriate for your child’s age and how to handle them can help you better respond to your child. “WHERE CAN I LEARN MORE ABOUT MY CHILD’S DEVELOPMENT?” If you are concerned about your child’s development or need more help, contact your child’s pediatrician, teacher, or school counselor. EMPOWERINGPARENTS.COM Articles from the experts at Empowering Parents to help you manage your teen’s behavior more effectively. Is your adolescent breaking curfew, behaving defiantly or engaging in risky behavior? We offer concrete help for teen behavior problems. www.empoweringparents.com AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS Adolescence can be a rough time for parents. At times, your teen may be a source of frustration and exasperation, not to mention financial stress. But these years also bring many, many moments of joy, pride, laughter and closeness. Find information about privacy, stress, mental health, and other health-related topics. www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/teen INFOABOUTKIDS.ORG This website has links to well-established, trustworthy websites with common parenting concerns related to your child’s body, mind, emotions, and relationships. infoaboutkids.org AHA! PARENTING Provides lots of great, useful advice on how to handle parenting challenges at all ages. -

L'influence De La Culture Catholique Sur Les Œuvres D'alfred Hitchcock Et De Pedro Almodóvar

L’influence de la culture catholique sur les œuvres d’Alfred Hitchcock et de Pedro Almodóvar Merve Sehirli Nasir To cite this version: Merve Sehirli Nasir. L’influence de la culture catholique sur les œuvres d’Alfred Hitchcock etde Pedro Almodóvar. Art et histoire de l’art. Université Jean Moulin (Lyon III), 2020. Français. NNT : 2020LYSE3011. tel-03146845v2 HAL Id: tel-03146845 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03146845v2 Submitted on 12 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N°d’ordre NNT : 2020LYSE3011 THÈSE de DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE LYON opérée au sein de L’Université Jean Moulin Lyon 3 Ecole Doctorale N° 484 Lettres, Langues, Linguistique et Arts Discipline de doctorat : Arts, cultures médiatiques et communication Soutenue publiquement le 18/02/2020, par : Merve SEHIRLI NASIR L'influence de la culture catholique sur les œuvres d'Alfred Hitchcock et de Pedro Almodóvar Devant le jury composé de : BARNIER Martin Professeur des universités, Université Lumière - Lyon 2, Président LE CORFF Isabelle Professeure des universités, -

Sculpting Women from Pygmalion to Vertigo to the Skin I Live In

1 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Quarterly Review of Film and Video Sculpting Women from Pygmalion to Vertigo to The Skin I Live in They would be displeased to have anybody call them docile, yet in a way they are . They submit themselves to manly behavior with all its risks and cruelties, its complicated burdens and deliberate frauds. Its rules, which in some cases you benefited from, as a woman, and then some that you didn’t. -“Too Much Happiness”, Alice Munro (294) One day I'll grow up, I'll be a beautiful woman. One day I'll grow up, I'll be a beautiful girl. But for today I am a child, for today I am a boy. -“For Today I Am a Boy”, Antony and the Johnsons The two images below (Figure 1) are from key moments in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and Pedro Almodóvar’s La piel que habito (The Skin I Live in, 2011). It is possible that there is a conscious citation here on the part of Almodóvar, but in any case the parallels are striking, and they reveal a great deal about gender as it is constructed in the mid- 20th century and the early 21st. Both shots show a woman gazed at from behind, as she herself is gazing at artwork that is especially significant for her sense of self. In the larger context of the films, both women are haunted by idealized images of femininity, which are necessary to prop up the crumbling masculinity of men who want to reshape their clothes, hair and bodies. -

PRESS RELEASE 06 Feb 2017 SPANISH & LATIN AMERICAN

HOME is a trading name of Greater Manchester Arts Ltd a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales No: 1681278 Registered office 2 Tony Wilson Place Manchester M15 4FN. Charity No: 514719 PRESS RELEASE 06 Feb 2017 Image credits: Sol Picó, One-Hit Wonders ; La Movida /Alejandría Cinque; Cien años de perdón (To Steal from a Thief) SPANISH & LATIN AMERICAN FESTIVAL ¡VIVA! RETURNS TO HOME WITH INTERNATIONAL FILM & THEATRE PREMIERES AND PIONEERING NEW GROUP EXHIBITION LA MOVIDA Fri 31 Mar – Mon 17 Apr 2017 • The popular festival returns with a venue-wide, 18-day celebration of Spanish and Latin American culture • ¡Viva! 2017 commemorates the 40th anniversary of the abolition of censorship in Spain, investigating the transition to democracy era (La Transición) • 29 films and 15 UK Premieres from new and established directors from 10 different countries including Spain, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela • Five international theatre productions including three UK Premieres and a World Premiere from Sol Picó, Agrupación Señor Serrano, Emma Frankland and Barcelona playwright Josep Maria Miró Coromina • HOME, CBRE, First Street and partners present three weekends of live music, dancing and performances, spilling out from HOME into Tony Wilson Place, featuring party nights, DJs plus Spanish-inspired cuisine & drinks • New group show La Movida , a pioneering contemporary exhibition exploring the artistic and socio-cultural movement of post-Franco Spain with new commissions by Luis -

Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel Huber David Jaramillo Gil The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3862 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] QUEER BAROQUE: SARDUY, PERLONGHER, LEMEBEL by HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL All Rights Reserved ii Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Carlos Riobó Chair of Examining Committee Date Carlos Riobó Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Paul Julian Smith Magdalena Perkowska THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil Advisor: Carlos Riobó Abstract: This dissertation analyzes the ways in which queer and trans people have been understood through verbal and visual baroque forms of representation in the social and cultural imaginary of Latin America, despite the various structural forces that have attempted to make them invisible and exclude them from the national narrative. -

Understanding the Market for Gender Confirmation Surgery in the Adult Transgender Community in the United States

Understanding the Market for Gender Confirmation Surgery in the Adult Transgender Community in the United States: Evolution of Treatment, Market Potential, and Unique Patient Characteristics The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Berhanu, Aaron Elias. 2016. Understanding the Market for Gender Confirmation Surgery in the Adult Transgender Community in the United States: Evolution of Treatment, Market Potential, and Unique Patient Characteristics. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Medical School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40620231 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Scholarly Report submitted in partial fulfillment of the MD Degree at Harvard Medical School Date: 1 March 2016 Student Name: Aaron Elias Berhanu, B.S. Scholarly Report Title: UNDERSTANDING THE MARKET FOR GENDER CONFIRMATION SURGERY IN THE ADULT TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY IN THE UNITED STATES: EVOLUTION OF TREATMENT, MARKET POTENTIAL, AND UNIQUE PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS Mentor Name and Affiliation: Richard Bartlett MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Harvard Medical School, Children’s Hospital of Boston Collaborators and Affiliations: None ! TITLE: Understanding the market for gender confirmation surgery in the adult transgender community in the United States: Evolution of treatment, market potential, and unique patient characteristics Aaron E Berhanu, Richard Bartlett Purpose: Estimate the size of the market for gender confirmation surgery and identify regions of the United States where the transgender population is underserved by surgical providers. -

Online Questionnaires

Online Questionnaires Re-thinking Transgenderism The Trans Research Review • Understanding online trans communities. • Comprehending present-day transvestism. • Inconsistent definitions of ‘transgenderism’ and the connected terms. • !Information regarding • Transphobia. • Family matters with trans people. • Employment issues concerning trans people. • Presentations of trans people within media. The Questionnaires • ‘Male-To-Female’ (‘MTF’) transsexual people [84 questions] ! • ‘MTF’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists [83 questions] ! • ‘Significant Others’ (Partners of trans people) [49 questions] ! • ‘Female To Male’ (‘FTM’) transsexual people [80 questions] ! • ‘FTM’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists [75 questions] ! • ‘Trans Admirers’ (Individuals attracted to trans people) • [50 questions] The Questionnaires 2nd Jan. 2007 to ~ 12th Dec. 2010 on the international Gender Society website and gained 390,227 inputs worldwide ‘Male-To-Female’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: Being 'In the closet' - transgendered only in private or Being 'Out of the closet' - transgendered in (some) public places 204 ‘Female-To-Male’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: Being 'In the closet' - transgendered only in private or Being 'Out of the closet' - transgendered in (some) public places 0.58 1 - Understanding online trans communities. Transgender Support/Help Websites ‘Male-To-Female’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: (679 responses) Always 41 Often 206 Sometimes 365 Never 67 0 100 200 300 400 1 - Understanding -

Safe Zone Training Special

Safe Zone Training School of Social Work Lunch & Learn Series Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. Interim Director - LGBTQ+ Center West Virginia University Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Outline • Policy • Gender 101: Basic definitions • Specific issues that affect the LGBTQ+ community • Institutional obstacles • Ways to assess your current work and organization • Inclusive language and solutions to positively impact your organizational climate • Learning to be a better ally and advocate Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Policy Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Gender 101: Basic Definitions Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Definitions • “LGBTQ+” is just a start. • Gender: humans have at least 5 chromosomal genders. Other genome and hormonal diversities mean there are many more possibilities for gender than two. Children begin to think about their gender identity around ages 2-4. • Cisgender people identify as the same gender attributed to them at birth. Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Definitions • Transgender may be an umbrella term to cover people whose gender identity does not match the sex assigned to them at birth. • Nonbinary people do not identify as male or female, finding the gender binary inadequate. • Intersex people are born with variations in gender beyond binary.1.7% of population. Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. WVU LGBTQ+ CENTER Legal recognition of non-binary gender Multiple countries legally recognize non-binary or third gender classifications. Argentina Austria Australia Canada Denmark Germany Iceland India The Netherlands Nepal New Zealand Pakistan Thailand United Kingdom United States Ellen Belchior Rodrigues, Ph.D. -

Introduction: Approaching Performance in Spanish Film

Introduction: approaching performance in Spanish film Dean Allbritton, Alejandro Melero and Tom Whittaker The importance of screen acting has often been overlooked in studies on Spanish film. While several critical works on Spanish cinema have centred on the cultural, social and industrial significance of stars, there has been relatively little critical scholarship on what stars are paid to do: act. This is perhaps surprising, given the central role that acting occupies within a film. In his essay ‘Why Study Film Acting?’, Paul McDonald argues that acting is not only crucial to understanding the affective charge of mov- ies, but integral to the study of film as a whole (2004: 40). Yet, despite its significance, performance remains one of the most elusive and difficult aspects of film analysis. One of the reasons for this, according to Pamela Robertson Wojcik, is its apparent transparency (2004: 1). A ‘good’ actor supposedly renders their performance ‘invisible’, thereby concealing the process of acting from the audience, and engaging us within the emo- tional universe of the character. To this effect, discussion on acting is all too frequently evaluative: we think in terms of how convincing or natu- ralistic a given performance is, or are invited to appreciate the actorly skills and techniques that are brought to bear on the film. Yet, when it comes to writing about performance academically, it can prove altogether more challenging. It requires us to single out and momentarily freeze the flow of specific moments of performance within a film, and to break them down to their tiniest details. We need to pay attention to what Paul McDonald has called the ‘micromeanings of the voice and body’ (2004: 40), intricately drawing out the ways in which gesture, body, facial expression and vocal delivery work together to cre- ate meaning. -

Spanish Videos Use the Find Function to Search This List

Spanish Videos Use the Find function to search this list Velázquez: The Nobleman of Painting 60 minutes, English. A compelling study of the Spanish artist and his relationship with King Philip IV, a patron of the arts who served as Velazquez’ sponsor. LLC Library – Call Number: SP 070 CALL NO. SP 070 Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness. LLC Library CALL NO. Look in German All About My Mother Director: Pedro Almodovar with Cecilia Roth, Penélope Cruz, Marisa Perdes, Candela Peña, Antonia San Juan. 1999, 102 minutes, Spanish with English subtitles. Pedro Almodovar delivers his finest film yet, a poignant masterpiece of unconditional love, survival and redemption. Manuela is the perfect mother. A hard-working nurse, she’s built a comfortable life for herself and her teenage son, an aspiring writer. But when tragedy strikes and her beloved only child is killed in a car accident, her world crumbles. The heartbroken woman learns her son’s final wish was to know of his father – the man she abandoned when she was pregnant 18 years earlier. Returning to Barcelona in search on him, Manuela overcomes her grief and becomes caregiver to a colorful extended family; a pregnant nun, a transvestite prostitute and two troubled actresses. With riveting performances, unforgettable characters and creative plot twists, this touching screwball melodrama is ‘an absolute stunner. -

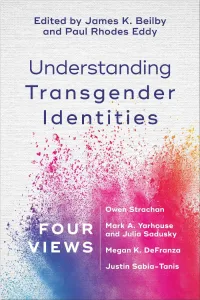

Understanding Transgender Identities

Understanding Transgender Identities FOUR VIEWS Edited by James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy K James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 3 9/11/19 8:21 AM Contents Acknowledgments ix Understanding Transgender Experiences and Identities: An Introduction Paul Rhodes Eddy and James K. Beilby 1 Transgender Experiences and Identities: A History 3 Transgender Experiences and Identities Today: Some Issues and Controversies 13 Transgender Experiences and Identities in Christian Perspective 44 Introducing Our Conversation 53 1. Transition or Transformation? A Moral- Theological Exploration of Christianity and Gender Dysphoria Owen Strachan 55 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 84 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 90 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 95 2. The Complexities of Gender Identity: Toward a More Nuanced Response to the Transgender Experience Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 101 Response by Owen Strachan 131 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 136 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 142 3. Good News for Gender Minorities Megan K. DeFranza 147 Response by Owen Strachan 179 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 184 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 190 vii James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 7 9/11/19 8:21 AM viii Contents 4. Holy Creation, Wholly Creative: God’s Intention for Gender Diversity Justin Sabia- Tanis 195 Response by Owen Strachan 223 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 228 Response by Megan K.