REPORT NO ABSTRACT Needs More Effectively and Economically. The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FORT BENNING SPONSORSHIP and ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES 1 Let Us Show You How to Reach America’S Finest

OCTOBER 2019 FORT BENNING SPONSORSHIP AND ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES 1 Let us show you how to reach America’s finest. The U.S. Army, Fort Benning Family and MWR Marketing team can help you secure a measurable return on investment and influential access to well- educated, diverse and financially stable consumers. Be part of something with value, purpose and reward. Align yourselves with something more. Make a meaningful difference. This is your opportunity to do well for those who have done so much. U.S. Army Family and MWR plans, produces, promotes and manages world-class programs for those who serve, including a host of recreation, sports, entertainment, travel and leisure activities. When you join our ranks and reach these coveted target markets with the U.S. Army, Fort Benning, you’ll also directly support exceptional programs for military members and their families. Thousands of military S ervice Members, Retirees and their Families count on our programs to boost their quality of life throughout Fort Benning and the surrounding military community. Here’s how you can help… 2 It’s one thing to plot a course. It’s another to navigate it. Nobody knows how to immerse your brand within the Fort Benning market better than our team. This is our terrain, and our audiences value authenticity and credibility of the brands that partner with us. Our mission is to help your brand develop meaningful and long-lasting relationships with the military consumer market. C reate awareness and visibility through customized marketing opportunities across multiple platforms: • Event sponsorships, Mobile Tour and Turn-key Event Access • Digital advertising (video screens, billboards and websites) • Online P romotions • Pass-through Rights with Military R etail Outlets (the E xchange/DeCA) • R egional, National and Global media exposure 3 2 So you want to reach your target? You’ve come to the right place. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

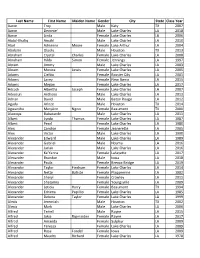

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

BAC Grad List

Last Name First Name Maiden Name Gender City State Class Year Aaron Troy Male Katy TX 2007 Aaron Devonte' Male Lake Charles LA 2018 Aaron Linda Female Lake Charles LA 2006 Abdul-Khaliq Amahl Male Lake Charles LA 2010 Abel Adrienne Moore Female Lake Arthur LA 2004 Abolarin Olaolu Male Houston TX 2013 Abraham Crystal Charles Female Lake Charles LA 2008 Abraham Hilda Simon Female Jennings LA 1997 Abram Jimmy Male Lake Charles LA 2003 Abram Monica Lewis Female Lake Charles LA 2005 Adams Cieltia Female Bossier City LA 2001 Adams Lacey Female New Iberia LA 2015 Adams Megan Female Lake Charles LA 2017 Adcock Albertha Joseph Female Lake Charles LA 2007 Adeosun Anthony Male Lake Charles LA 2013 Adrian David Male Baton Rouge LA 2012 Agada Arinze Male Houston TX 2014 Agwanihu MaryAnn Ngozi Female Beaumont TX 2000 Alawoya Babatunde Male Lake Charles LA 2011 Albert Lynda Thomas Female Lake Charles LA 1987 Albert Pearl Female Lake Charles LA 1980 Alex Candice Female Jeanerette LA 2005 Alex Victor Male Lake Charles LA 1990 Alexander Edward Male Lake Charles LA 1989 Alexander Gabriel Male Houma LA 2016 Alexander Jarian Male Lake Charles LA 2016 Alexander Ka'Yanna Female Lafayette LA 2017 Alexander Brandon Male Iowa LA 2018 Alexander Paula Female Breaux Bridge LA 2019 Alexander Taylor Finchum Female Lake Charles LA 2014 Alexander Nette Batiste Female Plaquemine LA 1992 Alexander Sheryl Female Crowley LA 2011 Alexander Shatamia Female Youngsville LA 2009 Alexander Leticia Harry Female Beaumont TX 1994 Alexander Edriena Papillio Female Lake Charles LA 1985 -

Chapter 6 the EARLY MODERN BRIGADE, 1958-1972 Pentomic

Chapter 6 THE EARLY MODERN BRIGADE, 1958-1972 Pentomic Era Following World War II, the US Army retained the organizational structures, with minor modifications, which had won that war. This organization—which did not include a maneuver unit called the brigade after the two brigades in the 1st Cavalry Division were eliminated in 1949—was also used to fight the Korean War in 1950-1953. Despite the success of the triangular infantry division in two wars, the Army radically changed the structure in 1958 by converting the infantry division to what became known as the Pentomic Division. Ostensively, the Pentomic structure was designed to allow infantry units to survive and fight on an atomic battlefield. Structurally it eliminated the regiment and battalion, replacing both with five self- contained “battlegroups,” each of which were larger than an old style battalion, but smaller than a regiment. A full colonel commanded the battlegroup and his captains commanded four, later five, subordinate rifle companies. The Pentomic Division structurally reflected that of the World War II European theater airborne divisions. This was no surprise since three European airborne commanders dominated the Army’s strategic thinking after the Korean War: Army Chief of Staff General Matthew Ridgway, Eighth Army commander General Maxwell Taylor, and VII Corps commander Lieutenant General James Gavin. Though theoretically triangular in design, the two airborne divisions Ridgway, Taylor, and Gavin commanded in the war, the 82d and 101st, fought as division task forces reinforced with additional parachute regiments and separate battalions. For most of the Northern European campaign, both divisions had two additional parachute regiments attached to them, giving them five subordinate regiments, each commanded by colonels. -

Fort Benning POST OVERVIEW

Fort Benning INTERSTATE POST OVERVIEW D A VICTOR D Y DRIVE O A VIC R TORY DRIV E O L R L I N H I D K R R H AR OW P A C H Y V M E A E R A 11800 M U D O L O W O L K N U T R O OA R S D S A T B P R A K G N E E D N E E A I T R T A C N Y 5631-8458 RO A R N F S E E D STE WETHERBY B IN R McGRAW CU T L FIELD O T VILLAGE T R E A E E O R MCGRAW F D E 6000 NEIGHBORHOOD R T OM ST CENTER S TR R ET D KE OS E MORRIS R. A A R HEA O BR ST OW D R B MCBRIDE R H 11300 ELEMENTARY T R AT E A GR SCHOOL E STARBUCKS MA R MCGRAW CUSTER VILLAGE T CHILD DEVELOPMENT S COMMUNITY CUSTER CENTER (CDC) S IVE CENTER T R TERRACE D 11306 T NATIONAL U 10309- E AD B L INFANTRY 10546 D DRIVE RO N R R MUSEUM A DRIVE E D L TE K IG S S K R RA S CUSTER CU EE A C KE OI CR V E TERRAC PAT E 10601-10746 U RANGE L 10754-10968 AREA B-1 U G CUSTER O I B B TERRACE S D G BATTLE PARK O N N AAFES I FIEL ARADE P HOMES INC. -

Bayside Homes Go Solar

AAPGPublishedP in the interestG of the people of AberdeenNNEWS Proving Ground,E MarylandWS www.TeamAPG.com THURSDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2015 Vol. 59, No. 41 APG North gate times to change BBaysideayside homeshomes gogo solarsolar Oct. 30 By YVONNE JOHNSON APG News In response to a recent survey querying driv- er preference, the senior installation command- er has directed that a test of gate operating hours be conducted at the APG North (Aberdeen) entry points. Starting Oct. 30, and running through Nov. 30, the Maryland Boule- vard (MD Rt. 715) gate will open 5 a.m. to 7 p.m., Monday – Friday and close weekends and the Harford Boulevard (MD Rt. 22) gate will open 24 hours-a-day. New APG North gate APG Garrison Commander Col. James E. Davis, right; Scott Kotwas, Corvias Military Living business director, center; and Keisha schedule: Brown, Corvias program development analyst, watch workers install solar panels on a Bayside Village home, Oct. 7. APG is MD 715: 5 a.m. to 7 p.m., the first Corvias installation to receive cost-saving solar panels through the Department of Defense Privatized Housing Solar Monday thru Friday Challenge initiative. MD 22: 24 hours-a day According to Director of Emergency Services Chris APG first Corvias installation to receive solar panels Ferris, the survey results from post residents and Story and photos by power on 210 home in the APG Bayside term and do something good for the environ- YVONNE JOHNSON members of the communi- community. The panels are expected to gen- ment by reducing annual carbon emissions,” APG News ty were overwhelmingly in erate 1,487 megawatt hours of solar power said Scott Kotwas, business director for Cor- favor of the change. -

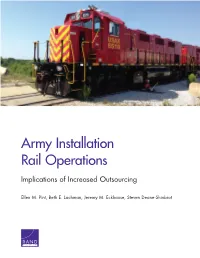

Army Installation Rail Operations: Implications of Increased Outsourcing

Army Installation Rail Operations Implications of Increased Outsourcing Ellen M. Pint, Beth E. Lachman, Jeremy M. Eckhause, Steven Deane-Shinbrot C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2009 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover photo of Fort Hood engine courtesy of Beth E. Lachman. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This document reports the results of a research project entitled Army Rail and Public-Private Partnerships. As part of this project, we compared the Army’s three business models for instal- lation rail operations: government owned, government operated (GOGO); government owned, contractor operated (GOCO); and privatized. -

America's Army

America’s Army 3 FAQ Updated: 5/13/2016 Table of Contents GAMEPLAY .............................................................................................................................................. 1 SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS ..................................................................................................................... 16 STEAM .................................................................................................................................................... 18 SERVERS ................................................................................................................................................. 23 PUNKBUSTER ........................................................................................................................................ 27 AMERICA’S ARMY 3.2 TRANSITION ...................................................................................................... 29 AMERICA’S ARMY 3.2 TRANSITION: DEPLOY CLIENT ....................................................................... 31 AMERICA’S ARMY 3.2 TRANSITION: GENERAL ................................................................................... 31 AMERICA’S ARMY 3.2 TRANSITION: WEB SITES ................................................................................. 32 AMERICA’S ARMY 3.2 TRANSITION: AA2 ............................................................................................. 32 AMERICA’S ARMY 3.2 TRANSITION: INSTALL / UNINSTALL ............................................................ -

The NCO Corps: the Strength of America's Army

Fiscal Year 2009 United States Army Annual Financial Statement The NCO Corps: The Strength of America’s Army 2009 Capital Fund General Fund and Working a A Soldier verifies cable connections and safety wires are all secure on the Land-Based Phalanx Weapon System gun cradle at Fort Sill, OK. Since 1775, the Army has set apart its NCOs from other enlisted Soldiers by distinctive insignia of grade. With more than 200 years of service, the U.S. Army’s Noncommissioned Officer (NCO) Corps has distinguished itself as the worlds most accomplished group of military professionals. Historical and daily accounts of life as an NCO are exemplified by acts of courage, and a dedication and a willingness to do whatever it takes to complete the mission. NCOs have been celebrated for decorated service in military events ranging from Valley Forge to Gettysburg, to charges on Omaha Beach and battles along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, to current conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. In recognition of their commitment to service and willingness to make great sacrifices on behalf of our nation, the Secretary of the Army established 2009 as the Year of the NCO. ON THE COVER: A Soldier demonstrates to an Iraqi child how to properly take a knee during Operation Warhorse Scimitar in west Mosul. The child was running up and down this alley way giving high fives to Soldiers. *Unless otherwise noted, all photos on the cover and inside pages are courtesy of the U.S. Army. (www.army.mil) FY 2009 Contents Message from the Secretary of the Army iii Message from the Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army (Financial Management and Comptroller) v Management’s Discussion & Analysis 1 General Fund – Principal Financial Statements, Notes, Supplementary Information and Auditor’s Report 27 Working Capital Fund – Principal Financial Statements, Notes and Auditor’s Report 93 Our NCO Corps is unrivaled by any Army in the world, envied by our allies and feared by our enemies. -

6/14/75 - Army Bicentennial, Fort Benning, Georgia” of the President’S Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 10, folder “6/14/75 - Army Bicentennial, Fort Benning, Georgia” of the President’s Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 10 of President's Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE PHESIDE!iT HAS SEEN dr?6 PRES IDENT'S REMARKS AT ARMY BICENTENNIAL DELEGATIONS • SECRETARY CALLAWAY • DISTINGUISHED GUESTS • LADIES AND GENTLEMEN 1 I - I - IT IS A GREAT HONOR ro BE HERE IN FORT BENNING, liTHE HOME OF THE INFANTRY ,ll AND TO JOIN WITH THE CI Tl ZENS OF COWMBUS AND PHENIX CITY AS WELL, TO MAKE THIS A REAL TR I-COMMUNITY CELEBRATION. YOU HAVE MADE COMING FROM THE BANKS OF THE POTOMAC TO THE VALLEY OF THE CHATTAHOOCHIE (CHAT-A-HOO-CHEE) A VERY MEMORABLE EXPERIENCE. ~-2- YOU KNOW, ONE OF THINGS I HAVE ALWAYS ADMIRED 4 ABOUT OUR MEN IN UNIFORM IS THEIR EVER-PRESENT SENSE OF HUMOR. -

Visit to Fort Benning” of the James M

The original documents are located in Box 47, folder “1975/06/14 - Visit to Fort Benning” of the James M. Cannon Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 47 of the James M. Cannon Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WAShiNGTON IT TO FORT BENNING • COLUMBUS, I -Departure: 7:55 A.M. From: Terry O'Donn;J<o~ BACKGROUND .. FORT BENNING The 20uth Anniversary Ceremony of the U.S. Army and the Infantry will be held at Fort Benning, Columbus, Georgia, Saturday, June 14, 1975. Fort Benning encompasses some 182,000 acres and is situated partly in Alabama and partly in Georgia on both sides of the Chattahoochee River. The "Home of the Infantry" as Fort Benning is called was namec after "'R .,.; cr r. "'""' ,., 1 l-f on .. ,r T ~ . .. ~ the Army George C. Marshall and Omar N. Bradley were one-time heads of the Infantry School at the Fort.