99 Getting Acquainted with the Pipils from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CEM ANAHUAC CONQUERORS Guillermo Marín

THE CEM ANAHUAC CONQUERORS Guillermo Marín Dedicated to the professor and friend Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, who illuminated me in the darkest nights. Tiger that eats in the bowels of the heart, stain its jaws the bloody night, and grows; and diminished grows old he who waits, while far away shines an irremediable fire. Rubén Bonifaz Nuño. Summary: The Cem Ānáhuac conquest has been going on for five centuries in a permanent struggle, sometimes violent and explosive, and most of the time via an underground resistance. The military conquest began by Nahua peoples of the Highlands as Spanish allies in 1521. At the fall of Tenochtitlan by Ixtlilxóchitl, the Spanish advance, throughout the territory, was made up by a small group of Spaniards and a large army composed of Nahua troops. The idea that at the fall of Tenochtitlan the entire Cem Anahuac fell is false. During the 16th century the military force and strategies were a combination of the Anahuaca and European knowledge, because both, during the Viceroyalty and in the Mexican Republic, anahuacas rebellions have been constant and bloody, the conquest has not concluded, the struggle continues. During the Spanish colony and the two centuries of Creole neo-colonialism, the troop of all armies were and continues to be, essentially composed of anahuacas. 1. The warrior and the Toltecáyotl Flowered Battle. Many peoples of the different ancient cultures and civilizations used the "Warrior" figure metaphorically. The human being who fights against the worst enemy: that dark being that dwells in the personal depths. A fight against weaknesses, errors and personal flaws, as the Jihad in the Islam religion. -

Ancient Tollan: the Sacred Precinct

100 RES 38 AUTUMN 2000 Figure 12. Upper section of Pillar 3: Personage with attributes of Tezcatlipoca. Photograph: Humberto Hiera. Ancient Toi Ian The sacred precinct ALBAGUADALUPE MASTACHE and ROBERTH. COBEAN Tula, along with Teotihuacan and Tenochtitlan, was to level the area for the plaza and to construct platforms one most of the important cities inMexico's Central that functioned as bases for buildings. Highlands. During Tula's apogee between a.d. 900-1150, It is evident that at Tula the placement of the area the city covered nearly 16 square kilometers. Its of monumental center is strategic, not only because it over an influence extended much of Central Mexico along occupies easily defended place but also because of its with other regions of Mesoamerica, including areas of central setting at a dominant point that had great visual the Baj?o, the Huasteca, the Gulf Coast, the Yucatan impact, being visible to inhabitants in every part of the city peninsula, and such distant places as the Soconusco, on and within view of many rural sites. Lefebvre observes that the Pacific Coast of Chiapas and Guatemala, and El a city's habitational zone ismade on a human scale, a Salvador. From cultural and ethnic perspective, Tula whereas the monumental zone has a superhuman scale, a constituted synthesis of principally two different which goes beyond human beings?overwhelming them, traditions: the preceding urban culture from Teotihuacan dazzling them. The monumental buildings' scale is the in the Basin of Mexico, and another tradition from the scale of divinity, of a divine ruler, of abstract institutions northern Mesoamerican periphery, especially the Baj?o that dominate human society (Lefebvre 1982:84). -

Perfil Departamental De El Quiché

Código PR-GI- 006 Versión 01 Perfil Departamental El Quiché Fecha de Emisión 24/03/17 Página 1 de 27 ESCUDO Y BANDERA MUNICIPAL DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE EL QUICHE Departamento de El Quiché Código PR-GI-006 Versión 01 Perfil Departamental Fecha de El Quiché Emisión 24/03/17 Página 2 de 27 1. Localización El departamento de El Quiché se encuentra situado en la región VII o región sur-occidente, la cabecera departamental es Santa Cruz del Quiché, limita al norte con México; al sur con los departamentos de Chimaltenango y Sololá; al este con los departamentos de Alta Verapaz y Baja Verapaz; y al oeste con los departamentos de Totonicapán y Huehuetenango. Se ubica en la latitud 15° 02' 12" y longitud 91° 07' 00", y cuenta con una extensión territorial de 8,378 kilómetros cuadrados, 15.33% de Valle, 84.67% de Montaña más de 17 nacimientos abastecen de agua para servicio domiciliar. Por la configuración geográfica que es bastante variada, sus alturas oscilan entre los 2,310 y 1,196 metros sobre el nivel del mar, por consiguiente los climas son muy variables, en los que predomina el frío y el templado. 2. Geografía El departamento de El Quiché está bañado por muchos ríos. Entre los principales sobresalen el río Chino o río Negro (que recorre los municipios de Sacapulas, Cunén, San Andrés Sajcabajá, Uspantán y Canillá, y posee la represa hidroeléctrica Chixoy); el río Blanco y el Pajarito (en Sacapulas); el río Azul y el río Los Encuentros (en Uspantán); el río Sibacá y el Cacabaj (en Chinique); y el río Grande o Motagua en Chiché. -

Highland Mexico Post Classic Aztec C. Andean South America Social Sciences Department HOLIDAY PARTY!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

WEEK OF THE DEAD December 1, 2014 XI Civilization D. New World b. Mesoamerica II: Highland Mexico Post Classic Aztec c. Andean South America Social Sciences Department HOLIDAY PARTY!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! This Friday, December 5 6:30 Home of Professor Harold Kerbo 2325 Tierra Drive, Los Osos Potluck!!!! Sign-Up in Department Office Building 47 Room 13d Major Prehistoric Civilizations 3600 B.C. 2000 B.C. 2500 B.C. 1500 B.C. ? Sub Saharan Africa A.D. 1000 3000 B.C. Years Isthmus Yucatan Valley of A.D./B.C. Mexico 1600 1500 + + 1400 + AZTEC 1300 + + 1200 POSTCLASSIC MAYA 1100 + + 1000 TOLTEC 900 + 800 + 700 + + 600 CLASSIC + MAYA 500 + + 400 + + 300 + + 200 + TEOTIHUACAN 100 A.D. + + 0 + + 100 B.C. + + 200 + + 300 + 400 PRE-CLASSIC MAYA 500 + + 600 + + 700 + + 800 + + 900 + + 1000 OLMEC + 1100 + + 1200 + + 1300 + + 1400 + + 1500 + + 1600 Olmec Culture Area (Isthmus of Tehuantepec) La Venta San Lorenzo Formative Culture: The Olmec (1500-500 B.C.) El Mirador Late Pre-Classic 200 B.C. – A.D. 250 El Mirador Pre-Classic Mayan City 300 B.C. to A.D. 250 Cultural Collapse and Abandonment A.D. 250 Tikal: Classic Maya City A.D. 250-850 CHICHEN ITZA Post Classic Maya 2. Mesoamerica II: Highland Mexico i. Teotihuacan: The Classic Period in Highland, Mexico Olmec Teotihuacan: City of the Gods Citadel and Temple of Quetzalcoatl Pyramid of the Sun Avenue of the Dead Pyramid of the Moon Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacan No ball courts documented at Teotihuacan Not popular in areas influenced by Teo • Associated with obsidian source • No true writing • True metallurgy by A.D. -

Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press

UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Title Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America: An Annotated Bibliography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68r4t3dq ISBN 978-1-938770-25-8 Publication Date 1979 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are within the manuscript. Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America: An Annotated Bibliography Second, Revised Edition Matthias Strecker MONOGRAPHX Institute of Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America: An Annotated Bibliography Second, Revised Edition Matthias Strecker MONOGRAPHX Institute of Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles ' eBook ISBN: 978-1-938770-25-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE By Brian D. Dillon . 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vi INTRODUCTION . 1 PART I: BIBLIOGRAPHY IN GEOGRAPHICAL ORDER 7 Tabasco and Chiapas . 9 Peninsula of Yucatan: C ampeche, Yucatan, Quintana Roo, Belize 11 Guatemala 13 El Salvador 15 Honduras 17 Nicaragua 19 Costa Rica 21 Panama 23 PART II: BIBLIOGRAPHY BY AUTHOR 25 NOTES 81 PREFACE Brian D. Dillon Matthias Strecker's Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America: An Annotated Bibliography originally appeared as a small edition in 1979 and quickly went out of print. Because of the volume of requests for additional copies and the influx of new or overlooked citations received since the first printing, production of a second , revised edition became necessary. More than half a hundred new ref erences in Spanish, English, German and French have been incorporated into this new edition and help Strecker's work to maintain its position as the most comprehen sive listing of rock art studies undertaken in Central America. -

Memorias De Piedra Verde: Miradas Simbólicas De Las Reliquias Toltecas

Memorias de piedra verde: miradas simbólicas de las reliquias toltecas Stephen Castillo Bernal* Museo Nacional de Antropología, INAH RESUMEN: Las placas de piedra verde son características del periodo Epiclásico (650-900 d.C.), en ellas se encuentran plasmadas las memorias de los guerreros, dignatarios y sacerdotes. Me- diante este texto se realiza un análisis simbólico y contextual de diversas placas recuperadas en los sitios de Xochicalco (650-900 d.C.) y de Tula (900-1200 d.C.), fundamentado en los significados simbólicos y anímicos que los toltecas le asignaron a esta clase de objetos. Al abrigo de la teoría del ritual de Victor Turner [1980, 1988], se avanza en una interpretación alterna de estos objetos, pues se ha asumido que ellos aluden a sacerdotes en estado de trance. Se postula también que los sujetos son representaciones de muertos, depositados como reliquias cargadas de meta-mensajes de tiempos pasados y que aparecen en contextos posteriores, como Tula o Tenochtitlan. PALABRAS CLAVE: Toltecas, piedra verde, reliquias, ancestros, muerte. Memories of green stone: A symbolic look at some Toltec relics ABSTRACT: Green stone slabs are characteristic of the Epiclassic period (650-900 A.D.). On them, warriors, dignitaries and priests were embodied. This paper provides a symbolic and contextual analysis of several of the said plates —in this case— recovered at the sites of Xochicalco (650-900 AD) and Tula (900-1200 AD), focusing specifically on the symbolic and emotional meanings that the Toltecs assigned to this class of object. From the ritual theory of Victor Turner [1980, 1988], an alternative interpretation of these objects is proposed, since it has been assumed that they allude to priests in a state of trance. -

Cultura No 8.Pdf

C U-L REVISTA BIMESTRAL DEL MINISTERIO DE CULTURA MINISTRO: DOCTOR REYNALDO GALINDO POHL SUB-SECRETARIO: DOCTOR ROBERTO MASFERRER DIRECTOR: SECRETARIO DE REDACCION: MANUEL ANDINO JUAN ANTONIO AYALA MARZO - ABRIL DEPARTAM~NTO&~ITORIAL DEL MINISTEROaE CULTURA Pasaje Contreros Nos. 11 y 13. SAN SALVADOR. EL SALVADOR. C. A. Impreso en los Talleres del DEPARTAMENTOED~TORIAL DEL MINISTERIOb~ CULTURA San Salvador, El Salvador, C. A. 1956 ' INDICE PAGINA Con un Novelista Insigne ........................................... Hugo Lindo. Entre la Selva de Neon .............................................. Alfonso Orantes. La Novela Social Nortearnericaria Reflejada en John Steinbeck ............. Rlario Hernhdez A. John Steinbeck y su Tecnica Literaria .................................. Juan Antonio Ayala. Francisco Morazan, Trinidad Cabanas y Gerardo Barrios .................. J. Ricardo Duenas V. S. El Hombre y el Tiempo .............................................. Salvador Canas. Dos Pasos Hacia Alfredo Espino ...................................... Cristobal Humberto Ibarra. Estampas de Meanguera del Golfo ................................... F. Raul Elas Reyes. PAGINA Peripecias de la Cultura en Centro'america .............................. Rafael Heliodoro. Valle. Breve Ensayo en Torno a la Consideracion del Tiempo y el Paisaje para la 'Auscultacion de la Poesia ......................................... Rolando Velasquez. Petronio, Personaje Inolvidable y Singular ............... Gustavo Pineda. Reportaje Sobre el Primer Congreso Pedagogico -

1413 PPM Santa María Nebaj

1 2 Contenido Presentación ................................................................................................................. 5 Introducción .................................................................................................................. 7 Capítulo I. Marco legal e institucional ....................................................................... 10 1.1. Marco legal ............................................................................................................. 10 1.2. Marco de política pública ........................................................................................ 11 1.3. Marco institucional .................................................................................................. 12 Capítulo II. Marco de referencia ................................................................................. 13 2.1. Ubicación geográfica .............................................................................................. 13 2.2. Delimitación y división administrativa ...................................................................... 14 2.3. Proyección poblacional ........................................................................................... 15 2.4. Educación ............................................................................................................... 16 2.5. Salud ...................................................................................................................... 16 2.6. Sector seguridad y justicia ..................................................................................... -

The PARI Journal Vol. XIV, No. 2

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume XIV, No. 2, Fall 2013 Mesoamerican Lexical Calques in Ancient Maya Writing and Imagery In This Issue: CHRISTOPHE HELMKE University of Copenhagen Mesoamerican Lexical Calques Introduction ancient cultural interactions which might otherwise go undetected. in Ancient Maya The process of calquing is a fascinating What follows is a preliminary treat- Writing and Imagery aspect of linguistics since it attests to ment of a small sample of Mesoamerican contacts between differing languages by lexical calques as attested in the glyphic and manifests itself in a variety of guises. Christophe Helmke corpus of the ancient Maya. The present Calquing involves loaning or transferring PAGES 1-15 treatment is not intended to be exhaus- items of vocabulary and even phonetic tive; instead it provides an insight into • and syntactic traits from one language 1 the types, antiquity, and longevity of to another. Here I would like to explore The Further Mesoamerican calques in the hopes that lexical calques, which is to say the loaning Adventures of Merle this foray may stimulate additional and of vocabulary items, not as loanwords, (continued) more in-depth treatment in the future. but by means of translating their mean- by ing from one language to another. In this Merle Greene sense calques can be thought of as “loan Calques in Mesoamerica Robertson translations,” in which only the semantic Lexical calques have occupied a privileged PAGES 16-20 dimension is borrowed. Calques, unlike place in the definition of Mesoamerica as a loanwords, are not liable to direct phono- linguistic area (Campbell et al. -

"Comments on the Historicity of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and the Toltecs" by Michael E

31 COMMENTARY "Comments on the Historicity of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and the Toltecs" by Michael E. Smith University at Albany, State University of New York Can we believe Aztec historical accounts about Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and other Toltec phenomena? The fascinating and important recent exchange in the Nahua Newsletter between H. B. Nicholson and Michel Graulich focused on this question. Stimulated partly by this debate and partly by a recent invitation to contribute an essay to an edited volume on Tula and Chichén Itzá (Smith n.d.), I have taken a new look at Aztec and Maya native historical traditions within the context of comparative oral histories from around the world. This exercise suggests that conquest-period native historical accounts are unlikely to preserve reliable information about events from the Early Postclassic period. Surviving accounts of the Toltecs, the Itzas (prior to Mayapan), Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tula, and Chichén Itzá all belong more to the realm of myth than history. In the spirit of encouraging discussion and debate, I offer a summary here of my views on early Aztec native history; a more complete version of which, including discussion of the Maya Chilam Balam accounts, will be published in Smith (n.d.). I have long thought that Mesoamericanists have been far too credulous in their acceptance of native historical sources; this is an example of what historian David Fischer (1970:58-61) calls "the fallacy of misplaced literalism." Aztec native history was an oral genre that employed painted books as mnemonic devices to aid the historian or scribe in their recitation (Calnek 1978; Nicholson 1971). -

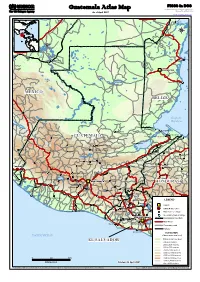

Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected] ((( Corozal Guatemala_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Balancan !! !! !! !! Tenosique Belize City !! BELMOPANBELMOPAN Stann Creek Town !! MEXICOMEXICO BELIZEBELIZE !! Golfo de Honduras San Juan ((( !! Lívingston !! El Achiotal !! Puerto Barrios GUATEMALAGUATEMALA Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla ((( ((( ((( Soloma ((( Cuyamel Cobán ((( El Estor ((( ((( Chajul ((( !! ((( San Pedro Carchá ((( Morales !! Motozintla Huehuetenango !! San Cristóbal Verapaz ((( Cunen ((( ((( !! Macuelizo ((( ((( Los Amates((( Petoa ((( Cubulco Salamá Trinidad ((( ((( !! Gualán ((( !! !! ((( !! ((( San Sebastián ((( San Jerónimo ((( Jesus Maria La Agua ((( !! Rabinal ((( Protección ((( Joyabaj TapachulaTapachula Totonicapán ((( Zacapa !! Naranjito ((( ((( !! Tapachula ((( ((( Santa Bárbara ((( Quezaltenango !! Dulce Nombre ((( !! San José Poaquil !! Chiquimula !! !! Sololá !! Santa Rosa !! Comalapa ((( Patzún !! Santiago Atitlán !! Tecun Uman !! Chimaltenango GUATEMALAGUATEMALA !! Jalapa HONDURASHONDURAS Mazatenango HONDURASHONDURAS Antigua ((( !! Esquipulas !! !! Retalhuleu ((( !! ((( Ciudad Vieja ((( Monjas Alotenango ((( Nueva Ocotepeque !! ((( Santa Catarina Mita Amatitlán ((( ((( Patulul ((( Ayarza Río Bravo ((( ((( Metapán !! !! Escuintla ((( !! ((( !! Jutiapa((( ((( !! Champerico ((( !! Cuilapa !! Asunción Mita ((( Yamarang Pueblo Nuevo Tiquisate ((( Erandique Yupiltepeque ((( ((( Atescatempa Nueva Concepción LEGEND -

Contemporary Art Music Compositions with Folkloric Elements of El Salvador

CONTEMPORARY ART MUSIC COMPOSITIONS WITH FOLKLORIC ELEMENTS OF EL SALVADOR RAUL PALOMO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST 2017 © RAUL PALOMO, 2017 Abstract There is a critical lack of ethnographic and ethnomusicological research that focuses in El Salvador’s indigenous (folkloric) music. Drawing on the historical studies and research of Santiago Ignacio Barberena and Dr. Jorge Lardé, as well as the ethnographic work of Maria de Baratta, I identify the elements of Cuzcatlán’s indigenous music and provide a brief overview of its history, rhythms, instruments, and forms. I then provide three original compositions that use the elements of Salvadoran folkloric music in a contemporary, art music settings. This work will be a reference source for future musicological research and compositional endeavors that might help keep an interest in Salvadoran folkloric music and create a renewed interest in its repertoire. ii Acknowledgements I have been infinitely blessed, in the pursuit of my dreams and music studies, to have been supported, guided, and advised by some of the most talented and heart-warming people. Their endless generosity, patience, and motivation ignited my volition and kept me from ever doubting myself and my goals. From the bottom of my heart, I would like to thank: • Chelsea Gassert, my other half, for her endless love and support. For always being there for me and pushing me to always work hard and keep moving forward with my chin held up high.