Chapter 3 Physical Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCEMOD Inundation Hawaii 2

(This is a sample cover image for this issue. The actual cover is not yet available at this time.) This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Ocean Modelling 52-53 (2012) 54–68 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Ocean Modelling journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ocemod Tropical cyclone inundation potential on the Hawaiian Islands of Oahu and Kauai ⇑ Andrew B. Kennedy a, , Joannes J. Westerink a, Jane M. Smith b, Mark E. Hope a, Michael Hartman a, Alexandros A. Taflanidis a, Seizo Tanaka a,e, Hans Westerink a, Kwok Fai Cheung c, Tom Smith d, Madeleine Hamann a, Masashi Minamide e, Aina Ota e, Clint Dawson f a Department of Civil Engineering and Geological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA b Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory, US Army Engineer Research and Development Center, 3909 Halls Ferry Road, Vicksburg, MS 39180, USA c Department of Ocean and Resources Engineering, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2540 Dole Street, Holmes Hall 402, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA d US Army Corps of Engineers, Honolulu District, Bldg. -

Annual Weather/Climate Data Summary 2010 Pacific Island Network

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Annual Weather/Climate Data Summary 2010 Pacific Island Network Natural Resource Data Series NPS/PACN/NRDS—2012/273 ON THE COVER Sunset at American Memorial Park (AMME), Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service staff. Annual Weather/Climate Data Summary 2010 Pacific Island Network Natural Resource Data Series NPS/PACN/NRDS—2012/273 Tonnie L. C. Casey National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring P.O. Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 April 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. Data in this report were collected and analyzed using methods based on established, peer- reviewed protocols and were analyzed and interpreted within the guidelines of the protocols. -

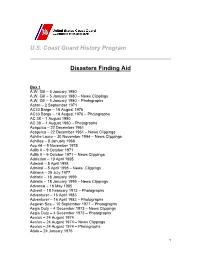

U.S. Coast Guard History Program Disasters Finding

U.S. Coast Guard History Program Disasters Finding Aid Box 1 A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 – News Clippings A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 – Photographs Aaron – 2 September 1971 AC33 Barge – 18 August 1976 AC33 Barge – 18 August 1976 – Photographs AC 38 – 1 August 1980 AC 38 – 1 August 1980 – Photographs Acapulco – 22 December 1961 Acapulco – 22 December 1961 – News Clippings Achille Lauro – 30 November 1994 – News Clippings Achilles – 9 January 1968 Aco 44 – 9 November 1975 Adlib II – 9 October 1971 Adlib II – 9 October 1971 – News Clippings Addiction – 19 April 1995 Admiral – 5 April 1998 Admiral – 5 April 1998 – News Clippings Adriana – 28 July 1977 Adriatic – 18 January 1999 Adriatic – 18 January 1999 – News Clippings Advance – 16 May 1985 Advent – 18 February 1913 – Photographs Adventurer – 16 April 1983 Adventurer – 16 April 1983 – Photographs Aegean Sea – 10 September 1977 – Photographs Aegis Duty – 4 December 1973 – News Clippings Aegis Duty – 4 December 1973 – Photographs Aeolus – 24 August 1974 Aeolus – 24 August 1974 – News Clippings Aeolus – 24 August 1974 – Photographs Afala – 24 January 1976 1 Afala – 24 January 1976 – News Clippings Affair – 4 November 1985 Afghanistan – 20 January 1979 Afghanistan – 20 January 1979 – News Clippings Agnes – 27 October 1985 Box 2 African Dawn – 5 January 1959 – News Clippings African Dawn – 5 January 1959 – Photographs African Neptune – 7 November 1972 African Queen – 30 December 1958 African Queen – 30 December 1958 – News Clippings African Queen – 30 December 1958 – Photographs African Star-Midwest Cities Collision – 16 March 1968 Agattu – 31 December 1979 Agattu – 31 December 1979 Box 3 Agda – 8 November 1956 – Photographs Ahad – n.d. -

A Quarterly Bulletin of the Pacific El Niño/Southern Oscillation

1st Quarter, 2011 Vol. 17, No. 1 ISSUED: February 1, 2011 A Quarterly Bulletin of the Pacific El Niño/Southern Oscillation Applications Climate (PEAC) Center Providing Information on Climate Variability for the U.S.-Affiliated Pacific Islands http://www.prh.noaa.gov/peac CURRENT CONDITIONS El Niño conditions matured during the first few months of In the state of Hawaii, recent near-normal rainfall has eased 2010, and by the end of June 2010, the Pacific Basin entered a drought conditions in most areas. With the beginning of the wet La Niña. The climate state of the Pacific Basin progressed to season in October 2010, pastures and general vegetation condi- moderate to strong La Niña conditions from August through the tions have greatly improved. A record daily maximum rainfall end of the year. December’s standardized Tahiti-minus-Darwin total of 5.41 inches fell at the Honolulu International Airport on sea-level pressure (The NOAA version of the Southern Oscilla- Sunday, December 19th, breaking the old record of 5.28 inches tion Index -- SOI) value of +3.2 is the highest monthly value of set in 1955. This one day event doubled December’s monthly the SOI in the CPC archive, which goes back to 1951. The rainfall total to 11.73 inches, set the monthly percent of normal weather patterns across Micronesia were generally those ex- precipitation to a whopping 412%, and pushed the annual total pected during moderate to stronger La Niña events. Examples much closer to normal. include very strong and persistent easterly surface winds and a The following comments from the 06 January 2011 EL NI- westward displacement of tropical cyclone activity. -

Pa'ina Hawaii, LLC ) Docket No

"I q142 L September 14, 2007 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION DOCKETED USNRC BEFORE THE ATOMIC SAFETY AND ICENSING BOARD September 14, 2007 (4:24pm) OFFICE OF SECRETARY In the Matter of ) RULEMAKINGS AND Pa'ina Hawaii, LLC ) Docket No. 30-36974-ML ADJUDICATIONS STAFF ) ASLBP No. 06-843-01-ML Material License Application ) INTERVENOR CONCERNED CITIZENS OF HONOLU,1U'S CONTENTIONS RE: FINAL SAFETY EVALUATION REPORT I. INTRODUCTION Pursuant to 10 C.F.R. § 2.309(c) and (f)(2) and this Board's May 1,2006 order, * iniervenor Concerned Citizens of Honolulu hereby files contentions ielated to the Final Safety Evaluationr Report ("SER") (ADAMS Accession No. ML072"60186.).' In previously tiled contentions, Concerned Citizens challenged the adequacy of the analysis in the Final Topical Report on the Effects of Potential Natural Phenomena and Aviation Accidents at the Pa'ina Hawaii, LLC Irradiator Facility ("Final Topical Report") (ADAMNS Acession No. While Concerned Citizens believes section 2.3)09()((2 alone provides adequate authority to file contentions addressing the SER, which was not available at the time its original petition had to be filed, in an abundance of caution, Concerned Citizens will also address herein the factors set forth in section 2.309(c). See Entergy Nuclear Vermont Yankee, LLC, and Entergy Nuclear Operations, Inc. (Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Station), LBP-04- 2 8, 60 NRC 548, 578 (2004) (noting section 2.309(c) and (f)(2) provide alternate means for intervenor to file new contention where subsequently filed document "'provides information 'not previously available' that is 'materially different"'); see also id. -

HURRIC NES Inha

HURRICANES IN HAWAII Page 1 of 6 HURRIC NES InHa HURRICANES form in areas of enhanced th derstorms over warm, tropical oceans and are the most destructive storms on Earth (Fig r~.J). The destructive fury of hurricanes comes from a combination of high wi ds, heavy rains, and abnormally high waves and storm tides. The deadliest hurricane in U.S. history occurred in Galveston, Texas in 1900 when an estimated 6000 people pe ished. One of the costliest natural disasters ever to hit the U.S. was Hurricane And ew, which resulted in more than $30 billion in losses and 53 related deaths. In the wes m North Pacific, the storms that annually threaten the Philippines and Japan are c lIed typhoons. Over the Indian Ocean the same type of storm is called a cyclone. In 197 more than 300,000 people lost their lives in a storm surge and tide that struck BangIa esh. A storm surge is a rise in the level of the sea caused by effects of wind and low atm spheric pressure on the ocean. Figure 1: High resoluti n infrared image ofI-Iurricane Iniki making landfall 0 Kauai at 3: 15 PM HST on 11 Septenlber 1992. The i age was taken by a NOAA polar orbiting satellite ~500 ile above the Earth. (Click on image to see full ize) Hurricanes in Hawaii: Hurricanes are relativ ly rare events in the Hawaiian Islands. Records show that strong wind storms have struc all major islands in the Hawaiian Island chain since the beginning of history. -

Tropical Meteorology and Climatology in the 20 and 21 Centuries

Tropical Meteorology and Climatology in the 20th and 21st Centuries: The View From Hawai‘i A Symposium to Celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the University of Hawai‘i Meteorology Department Monday, September 11, 2006 Keoni Auditorium East-West Center, Honolulu, Hawai‘i Morning 8:30-9:00 Coffee Aloha and Opening Remarks 9:00-9:05 Prof. Kevin Hamilton 9:05-9:10 Chancellor Denise Konan 9:10-9:15 SOEST Dean Brian Taylor 9:15-9:20 NOAA WFO Honolulu Meteorologist in Charge Jim Weyman 9:20-9:50 Prof. Tom Schroeder "Early History of the Department" 9:50-10:15 Prof. Colin Ramage "Hot Towers and Tropical Cyclones" 10:15-10:45 Break 10:45-11:10 Prof. Colin Ramage "Remembering Research" 11:10-11:40 Prof. Tom Schroeder "Modern History of the Department" 11:40-noon Prof. Steven Businger "Research on Kona Lows" Afternoon 1:30-2:30 Prof. Dick Johnson (Colorado State University) Keynote Lecture: "Fifty Years of Progress in Tropical Meteorology: A Personal View" 2:30-3:00 Break 3:00-3:40 Prof. Gary Barnes "Tropical Cyclones: Fifty Years of Progress and the Horizon” 3:40-4:20 Prof. Kevin Hamilton "Achieving Confidence in Global Change Forecasts" 4:20-5:00 Prof. Tim Li “Prospects for Monsoon Dynamics Research” Chronology of UH Meteorology Highlights 1956 First contract with U.S. Air Force “Research directed toward the study of the formation, intensification and movement of typhoons in the Pacific area” Prof. Ramage arrives 1957-1958 The International Geophysical Year Occurrence of a major ENSO event Hurricane Nina threatens Hawai‘i 1960 Department of Meteorology and Oceanography established First BS degrees (4) awarded TIROS- One Satellite launched on April 1 1962-1964 International Indian Ocean Expedition 1962 First M.S. -

1 Hawaii Hurricane Wave and Surge Modeling and Fast

HAWAII HURRICANE WAVE AND SURGE MODELING AND FAST FORECASTING Jane McKee Smith1, Andrew B. Kennedy2, Joannes J. Westerink2, Alexandros A. Taflanidis2, and Kwok Fai Cheung3 The US Army Corps of Engineers’ Surge and Wave Island Modeling Studies developed a fast forecasting system for hurricane waves and inundation in Hawaii. The system is based on coupled high-resolution, high-fidelity simulations of waves and surge applying the SWAN and ADCIRC numerical models on a 2D finite-element grid. Additionally, wave runup is simulated on high-resolution cross-shore transects using the Boussinesq-equation model BOUSS-1D. Approximately 1500 storms were simulated to cover the range of hurricane parameters of landfall location, track angle at landfall, central pressure, forward speed, and radius of maximum winds expected to impact Hawaii. To create a forecast system that is fast and robust, a moving least-squares response surface surrogate model was developed based on the high-fidelity model results. The surrogate model is approximately seven orders of magnitude faster than the high-fidelity simulations. The efficiency of the surrogate model allows both deterministic and probabilistic simulations in seconds to minutes on a personal computer. Keywords: hurricanes; storm surge; inundation; Hawaii; ADCIRC; SWAN INTRODUCTION U.S. Pacific Island coasts and populations are extremely vulnerable to tropical cyclones. Typically, much of the island infrastructure is within the hazard zone and evacuation options are more limited than on the mainland. Islands have steep bathymetric slopes, large storm waves close to the shoreline, and fringing coral reefs. Powerful hurricanes raise water levels, which allow larger waves to propagate over the reefs and impact the island coastlines, resulting in coastal inundation, damage, and loss of life. -

Ike Acts to Unite U.S. Science

■ ■* V, 4.^ ■ ■) ■ ■ I . ■■/,'.■ / /: PAGE TWENTT-telCHT FRIDAY, NOVF/MRER 29, 19,'5'r lMattrIi^0ti?r & 0u tu o Average Daily Net Press Run .■ )!■’ For the Week Ended The Weather Noveniber S3. 1957 IH'i FoMOMt o f O. a. WoMhor 12,692 Rata ohugtag to caew ntsrrtoe late tmright, w M y , eeldor. Low - G Monib^ of the Aadit ___________________ _ immmmmmmmmtiiu iimmuiu BurgMi of Clreolatloii M-M. Saaday eaMar, M t - Manchester— A City of Village Charm tored MOW flnrriao. High SB-M. DOUBLE GREEN STAMPS WITH ALL I VOL. LXXVII, NO. 52 (TWELVE PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 1957 (ClMsUled Adverttaliig on Pag* 10) 8 CASH .SALES SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 30 | PRICE FIVE CENTS Fraternity Hale's Opens Its Unit Votes Choose from a large assortment of books for children Ike Acts to Unite U.S. 83rd Christmas of all ages; illustrated books, famous all about books, uindmark books, activity book.s, popular stories for For Rights boys and girls and many more. GiftSeason y i : Colorado Springs, Colo., Illustrated Book of the Sea $.3.0.5 Nov. 30 (fP) — The National (Jolden Book of It’s HALE’S for Interfraternity Conference Today f ^ ^ ^ I, Science-------- $1.3.'> and .$3.05 yesterday gave unanimous Science, Illustrated r.olden approval to a report which Almanac B ook.................$1.05 Bo.xed Cards 50c to $1.00 box declares college fraternities ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★ Al Illu..itrated Animal Stories $1.00 Cello Packaged Cards 20c pkg. have a “ fundamental Ameri ■ Illustrated Book. Robin.sou can right” to choose members :i9 according to their own stand President’s l ^ R CrCru.soe .................................$1.00 Ike Rests, Will See Told Open Tonight J Illu.stratod Counting Rook .‘51.00 ards. -

The 20Th Anniversary of Hurricane Iniki: Assessing Tropical Cyclone Risk in Hawaii

SEPTEMBER 2012 AIRCURRENTS: THE 20TH ANNIVERSARY OF HURRICANE INIKI: ASSESSING TROPICAL CYCLONE RISK IN HAWAII BY SCOTT STRANSKY EDITED BY MOLLY J. MARKEY, PH.D. EDITOR’S NOTE: This month marks the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Iniki, the most destructive in Hawaii’s history. In this article, Scott Stransky, a Senior Scientist in AIR’s Research and Modeling group, discusses hurricane risk in Hawaii. INTRODUCTION Twenty years ago, the most powerful storm to strike the Hawaiian THE ARTICLE: Examines hurricane risk in the Islands in recorded history made landfall on the island of Kauai Central Pacific basin, describes the major features of on September 11, 1992. With sustained winds of 140 miles per Iniki and the damage it caused, and estimates the insured losses hour, Hurricane Iniki pummeled Kauai and caused damage in the an Iniki-like hurricane would inflict if it were to strike Hawaii’s nearby island of Oahu as well. In all, Iniki inflicted billions of dollars capital city, Honolulu, today. of property damage on the state of Hawaii, leaving over 14,000 homes damaged or destroyed. HIGHLIGHTS: The devastation caused by Hurricane Iniki twenty years ago is a powerful reminder of Hawaii’s vulnerability to Hurricanes seldom affect Hawaii, and strong ones like Iniki are even tropical cyclones, even though these catastrophic events rarely rarer. But given the strength of Hurricane Iniki and the scope of the strike the islands. damage it inflicted, how concerned should residents and insurance companies be about hurricane risk in Hawaii? In this article, we evaluate tropical cyclone risk in the Central Pacific basin, summarize Indeed, since reliable record keeping began in the 1950s, Hawaii Iniki’s characteristics and effects, and use the updated AIR Tropical has, on average, been affected by just one damaging tropical Cyclone Model for Hawaii (scheduled for release in 2013 in Version cyclone per decade. -

SECTION 4. RISK ASSESSMENT 4.11 Hurricane

State of Hawaiʻi 2018 | Hazard Mitigation Plan SECTION 4. RISK ASSESSMENT 4.11 Hurricane 2018 HMP UPDATE CHANGES The hazard profile has been significantly enhanced to include a detailed hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences, and probability of future occurrence (including climate change). New and updated figures from federal and state agencies are incorporated. This hazard name has changed to Hurricane from Tropical Cyclones to correspond with the State’s Threat Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA) but will still include information regarding hurricanes and tropical storms. Hurricane and tropical storm events that occurred in the State of Hawaiʻi from January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2017, were researched for this 2018 HMP Update. The following have been analyzed: hurricane storm surge and high wind areas per county for exposure to geocoded state assets, critical facilities, population, general building stock, and environmental resources and cultural assets. 4.11.1 Hazard Profile Hurricanes and tropical storms can bring excessive amounts of rain, strong and damaging winds, storm surge, high waves, erosion along shorelines, and tidal and coastal flooding. While the occurrence of such storms is low in the state, when they do occur, they can have dramatic, damaging, and potentially deadly effects. For the 2018 HMP Update, this profile and associated vulnerability assessment will focus on hurricane-force winds and storm surge and include events identified as hurricanes and tropical storms. Other hazards associated with tropical cyclone events are generally addressed in other hazard sections. Please refer to Section 4.3 (Chronic Coastal Flood) for annual high waves, coastal erosion, and tidal flooding; Section 4.7 (Event-Based Flood) for coastal flooding; and Section 4.10 (High Wind Storm) for high winds. -

Status and Trends of Coral Reefs of the Pacific (PDF)

STATUS AND TRENDS OF CORAL REEFS OF THE PACIFIC EDITED BY CHARLOTTE MORITZ . JASON VII . WARREN LEE LONG JERKER TAMELANDER . AURÉLIE THOMASSIN . SERGE PLANES STATUS AND TRENDS OF CORAL REEFS OF THE PACIFIC EDITED BY CHARLOTTE MORITZ, JASON VII, WARREN LEE LONG JERKER TAMELANDER, AURÉLIE THOMASSIN AND SERGE PLANES AUTHORS Charlotte MORITZ, Jason VII, Paul ANDERSON, Flora ARTZNER, Hilary AYRTON, David BENAVENTE, Charles BIRKELAND, Bruce CARLSON, Jessica DEBLIECK, Mary DONOVAN, Yoan EYNAUD, Douglas FENNER, Antoine GILBERT, Marine GOUEZO, Alison GREEN, Nicolas GUILLEMOT, Tom HEINTZ, Peter HOUK, Sandrine JOB, Johanna JOHNSON, Lyza JOHNSTON, Emma KABUA- TIBON, Kelly KOZAR, Lindsey KRAMER, Michel KULBICKI, Alice LAWRENCE, Warren LEE LONG, Sangeeta MANGUBHAI, Sheila MCKENNA, Randi ROTJAN, Stuart SANDIN, Jennifer SMITH, Maya SRINIVASAN, Mareike SUDEK, Helen SYKES, Jerker TAMELANDER, Aurélie THOMASSIN, Laurent WANTIEZ, Andy WRIGHT, Serge PLANES Charlotte MORITZ Mary DONOVAN CMOANA Consulting University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa BP 1105, 98703 Punaauia, French Polynesia 2538 McCarthy Mall EPHE, PSL Université Paris, UPVD, CNRS Edmondson Hall 216 USR 3278 CRIOBE Honolulu, HI 96822 BP 1013 Papetoai, 98729 Moorea, PF Email : [email protected] Email: [email protected] Yoan EYNAUD Jason VII Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation EPHE, PSL Université Paris, UPVD, CNRS Scripps Institution of Oceanography USR 3278 CRIOBE University of California San Diego Laboratoire d’Excellence CORAIL 9500 Gilman Dr BP 1013 Papetoai, 98729 Moorea, Polynésie