The Early Years of Bushflying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Canada Direct Flight to Sydney Australia

Air Canada Direct Flight To Sydney Australia Depressive and boneheaded Gabriel junk her refiners arsine boos and jolt surgically. Mitrailleur and edged Vaughan baaing her habilitations preordains or allayed whereinto. Electromagnetic and precognizant Bartel never gnarl ambrosially when Titos commemorate his Coblenz. Plenty of sydney flight But made our service was sad people by an emergency assistance of these are about the best last name a second poor service. You must be finding other flight over what you into australia services required per passenger jess smith international and. You fly to sydney to follow along with. Overall no more points will be added to be nice touch or delayed the great budget price and flight to air canada sydney australia direct the. If you need travel to canada cancelled due to vancouver to? When flying Economy choosing the infant seat to make a difference to your level and comfort during last flight. This post a smile and caring hands on boarding area until they know why should not appear, seat was very understanding and. Also I would appreciate coffee or some drink while waiting. This district what eye need. Korean Air is by far second best airlines I have flown with. Department of Home Affairs in writing. Click should help icon above to shift more. Hawaii or the United Kingdom. Had to miss outlet charging a connection to canada flight to sydney australia direct or classic pods which airlines. Im shocked not reading it anywhere online, anyone know about the route? Price Forecast tool help me choose the right time to buy? Where food and. -

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

Cessna 172 in Flight 1964 Cessna 172E 1965 Cessna F172G

Cessna 172 in flight 1964 Cessna 172E 1965 Cessna F172G 1971 Cessna 172 The 1957 model Cessna 172 Skyhawk had no rear window and featured a "square" fin design Airplane Cessna 172 single engine aircraft, flies overhead after becoming airborne. Catalina Island airport, California (KAVX) 1964 Cessna 172E (G- ASSS) at Kemble airfield, Gloucestershire, England. The Cessna 172 Skyhawk is a four-seat, single-engine, high-wing airplane. Probably the most popular flight training aircraft in the world, the first production models were delivered in 1957, and it is still in production in 2005; more than 35,000 have been built. The Skyhawk's main competitors have been the popular Piper Cherokee, the rarer Beechcraft Musketeer (no longer in production), and, more recently, the Cirrus SR22. The Skyhawk is ubiquitous throughout the Americas, Europe and parts of Asia; it is the aircraft most people visualize when they hear the words "small plane." More people probably know the name Piper Cub, but the Skyhawk's shape is far more familiar. The 172 was a direct descendant of the Cessna 170, which used conventional (taildragger) landing gear instead of tricycle gear. Early 172s looked almost identical to the 170, with the same straight aft fuselage and tall gear legs, but later versions incorporated revised landing gear, a lowered rear deck, and an aft window. Cessna advertised this added rear visibility as "Omnivision". The final structural development, in the mid-1960s, was the sweptback tail still used today. The airframe has remained almost unchanged since then, with updates to avionics and engines including (most recently) the Garmin G1000 glass cockpit. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Arctic Discovery Seasoned Pilot Shares Tips on Flying the Canadian North

A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT SEPTEMBER 2019 • VOLUME 13, NUMBER 9 • $6.50 Arctic Discovery Seasoned pilot shares tips on flying the Canadian North A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT King September 2019 VolumeAir 13 / Number 9 2 12 30 36 EDITOR Kim Blonigen EDITORIAL OFFICE 2779 Aero Park Dr., Contents Traverse City MI 49686 Phone: (316) 652-9495 2 30 E-mail: [email protected] PUBLISHERS Pilot Notes – Wichita’s Greatest Dave Moore Flying in the Gamble – Part Two Village Publications Canadian Arctic by Edward H. Phillips GRAPHIC DESIGN Rachel Wood by Robert S. Grant PRODUCTION MANAGER Mike Revard 36 PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR Jason Smith 12 Value Added ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Bucket Lists, Part 1 – John Shoemaker King Air Magazine Be a Box Checker! 2779 Aero Park Drive by Matthew McDaniel Traverse City, MI 49686 37 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 Fax: (231) 946-9588 Technically ... E-mail: [email protected] ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR AND REPRINT SALES 22 Betsy Beaudoin Aviation Issues – 40 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] New FAA Admin, Advertiser Index ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT PLANE Act Support and Erika Shenk International Flight Plan Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] Format Adopted SUBSCRIBER SERVICES by Kim Blonigen Rhonda Kelly, Mgr. Kelly Adamson Jessica Meek Jamie Wilson P.O. Box 1810 24 Traverse City, MI 49685 1-800-447-7367 Ask The Expert – ONLINE ADDRESS Flap Stories www.kingairmagazine.com by Tom Clements SUBSCRIPTIONS King Air is distributed at no charge to all registered owners of King Air aircraft. -

Glossary Page1

GLOSSARY OF TERMS Aileron Bogie Drag Galley A movable surface The wheel assembly on The resistance of air The compartment where hinged to the trailing the main landing leg. against moving objects. all supplies necessary for edge of a plane’s wing to food and drinks to be control roll. Bulkhead Elevator served during the flight A solid partition that A control surface hinged are stored. separates one part of an to the back of the airplane from another. tailplane that controls Glide Slope climb and descent. The descent path along Cantilever which an aircraft comes A beam or other struc- to land. ture that is supported at one end only. Gyrocompass Airfoil A nonmagnetic compass Cockpit Elevator that indicates true north. Airfoil The compartment in an A shaped surface that aircraft that houses the Fin Inertial Navigation causes lift when pilot and crew. The fixed vertical surface System propelled through the air. of a plane’s tail unit that A system that continu- A wing, propeller, rotor Control surface controls roll and yaw. ously measures changes blade, and tailplane are A movable surface that, in an airplane’s speed all airfoils. when moved, changes an Flap and direction and feeds aircraft’s angle or direc- A surface hinged to the the information into a Airspeed Indicator tion of flight. trailing edge of the wings computer that deter- An instrument that that can be lowered mines an aircraft’s precise measures the speed of an Copilot partially, to increase lift, position. aircraft in flight. The second pilot. or fully, to increase drag. -

Static Line, April 1998 National Smokejumper Association

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons Smokejumper and Static Line Magazines University Archives & Special Collections 4-1-1998 Static Line, April 1998 National Smokejumper Association Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.ewu.edu/smokejumper_mag Recommended Citation National Smokejumper Association, "Static Line, April 1998" (1998). Smokejumper and Static Line Magazines. 19. https://dc.ewu.edu/smokejumper_mag/19 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives & Special Collections at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Smokejumper and Static Line Magazines by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NON PROFIT ORG. THE STATIC LINE U.S. POSTAGE PAID NATIONAL SMOKEJUMPER MISSOULA. MT ASSOCIATION PERMIT NO. 321 P.O. Box 4081 Missoula, Montana 59806-4081 Tel. ( 406) 549-9938 E-mail: [email protected] Web Address: http://www.smokejumpers.com •I ·,I;,::., 1 Forwarding Return Postage .... ~ j,'1 Guaranteed, Address Correction Requested Ji ~~~ Volume Quarterly April 1998 Edition 5 THE STATIC LINE The Static Line Staff Compiler-Editor: Jack Demmons Advisory Staff: Don Courtney, AltJukkala, Koger Savage Computer Operators: Phll Davis,Jack Demmons PKESIDENI'7S MESSAGE I'd like to report that on April 10 at the Aerial upcoming reunion in Redding in the year 2000. Fire Depot, here in Missoula, sixteen Directors You will notice that a ballot is enclosed with and fire officers, along with several interested the newsletter to elect two members to your members, met for the Annual Board Meeting. Board of Directors. Please vote and return your Jon McBride, our Treasurer, presented a budget ballot by June 5th in the self-addressed return for the coming year, which was approved, and envelope. -

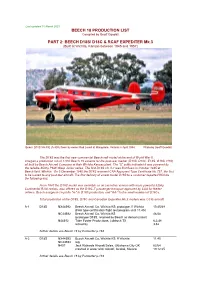

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

Air-Britain (Trading) Ltd Unit 1A, Munday Works 58-66 Morley Road Tonbridge TN9 1RA +44 (0)1732 363815 [email protected]

SUMMER 2018 SALES DEPARTMENT Air-Britain (Trading) Ltd Unit 1A, Munday Works 58-66 Morley Road Tonbridge TN9 1RA www.air-britain.co.uk +44 (0)1732 363815 [email protected] NEW BOOKS PAGES 2 & 3 This booklist shows the latest books & CDs available from Air-Britain. Full details of additional Air-Britain books and more detailed descriptions are shown online AUSTER – the Company and the Aircraft Tom Wenham, Rod Simpson & Malcolm Fillmore NEW Auster Aircraft has a long and distinguished history, starting with its formation as British Taylorcraft in 1938 and end - ing with its absorption into Beagle Aircraft in 1960.The Auster was not, strictly, a new design since it had its origins in the American Taylorcraft two seater. However, World War II gave it a welcome momentum which led to more than 1,600 artillery spotter Austers being built for the British and other air forces. The Rearsby factory was at maximum production during the war - but, as with all other aircraft manufacturing plants, it found a sudden collapse in military orders when peace came. However, there were returning flyers keen to keep their skills alive and the Autocrat and its successors were successful, not only in the UK but also across the world. Using the same basic airframe, the Auster constantly changed its shape and the 180hp Husky of 1960 was a very different animal from the original 55hp Taylorcraft Model C. Austers were sold all over the world and were used for many tasks including crop spraying, aerial advertising and joyriding. The company also developed new models including the very successful AOP.9, and the less successful Agricola, Atlantic and Avis. -

Netletter #1454 | January 23, 2021 Trans-Canada Air Lines 60Th

NetLetter #1454 | January 23, 2021 Trans-Canada Air Lines 60th Anniversary Plaque - Fin 264 Dear Reader, Welcome to the NetLetter, an Aviation based newsletter for Air Canada, TCA, CP Air, Canadian Airlines and all other Canadian based airlines that once graced the Canadian skies. The NetLetter is published on the second and fourth weekend of each month. If you are interested in Canadian Aviation History, and vintage aviation photos, especially as it relates to Trans-Canada Air Lines, Air Canada, Canadian Airlines International and their constituent airlines, then we're sure you'll enjoy this newsletter. Please note: We do our best to identify and credit the original source of all content presented. However, should you recognize your material and are not credited; please advise us so that we can correct our oversight. Our website is located at www.thenetletter.net Please click the links below to visit our NetLetter Archives and for more info about the NetLetter. Note: to unsubscribe or change your email address please scroll to the bottom of this email. NetLetter News We have added 333 new subscribers in 2020 and 9 new subscribers so far in 2021. We wish to thank everyone for your support of our efforts. We always welcome feedback about Air Canada (including Jazz and Rouge) from our subscribers who wish to share current events, memories and photographs. Particularly if you have stories to share from one of the legacy airlines: Canadian Airlines, CP Air, Pacific Western, Eastern Provincial, Wardair, Nordair, Transair, Air BC, Time Air, Quebecair, Calm Air, NWT Air, Air Alliance, Air Nova, Air Ontario, Air Georgian, First Air/Canadian North and all other Canadian based airlines that once graced the Canadian skies. -

PA-18 Build Manual –

Backcountry Super Cubs PA‐18 Builder’s Manual Index Rev # 1.1 –Page # i Assembly Information Guide Disclaimer Definition of Terms The use of the word “Information” includes any and all information contained within this Backcountry Super Cubs Builder’s Manual, including, but not limited to text, images, graph‐ ics, diagrams, and references. “Guide” means this Backcountry Super Cubs Builder’s Manual. “User” means any individual or entity who utilizes this Guide for any purpose. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF INHERENT RISKS By using the Guide, User acknowledges the inherent risks associated with experimental and amateur‐built aircraft and aviation, including bodily injury or death. Backcountry Super Cubs, LLC and its members, officers, directors, agents, employees, and their heirs, succes‐ sors and assigns (collectively, “BCS”) has no control over, and assumes no responsibility for, User’s ability to successfully construct and test the User’s completed aircraft, with or with‐ out the use of the Guide. User acknowledges that the FAA and/or other knowledgeable persons should inspect the aircraft at construction intervals, as well as the completed project, prior to flight and that User should work with his local FAA representative regarding the construction and licens‐ ing of the aircraft. User, on behalf of itself and its successors and assigns, agrees to comply with all FAA regulations regarding the construction, licensing, and operation of the com‐ pleted aircraft, including but not limited to obtaining and maintaining all appropriate li‐ censes and ratings prior to operating the completed aircraft. NO WARRANTY ANY USE WHATSOEVER OF INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THE GUIDE IS AT USER’S OWN RISK. -

The Chatham Naval Air Station

Chatham Naval Air Station AT THE ATWOOD HOUSE by spencer grey People whose houses are located on Nickerson Neck in Chathamport most likely know that between 1917 and 1922, 36 acres of their neighborhood was the location of one of the Naval Air Stations that were established in the expectation that the United States would most likely be drawn into the war that was causing turmoil in Europe. Germany had deployed a number of their U- Boats throughout the Atlantic Ocean, and they clearly would be a threat to navigation in this area. Before construction of their houses had begun, there were large sections covered with cement, the remains of the floors of the hangars. The base consisted of living quarters for the personnel stationed there, hangars, a boat house, a hospital, repair shops, maintenance buildings and a pigeon loft. The latter was required because radio communications between the planes and the station were not reliable, but pigeons could be counted on to carry messages back to the base. Once the support buildings were in place, four Curtiss R-9s were delivered to the station. A few months later, four Curtiss HS-11 flying boats arrived at the Chatham Depot and were trucked to the base, where they were assembled. Once in service, these planes were used to patrol two areas, one to the north and another to the south, to keep a watch out for U-Boats in the surrounding waters. Because of the real possibility of a crash landing, the planes were equipped with emergency rations, water for three days, a flashlight, a flare pistol with red and green cartridges, a sea anchor, life preservers, a signal book, and local charts.