Project Finance in Practice: Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report & Accounts 2013

Annual Report & Accounts 2013 Annual Report & Accounts 2013 Annual Report & Accounts Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC 22706.04 13 December 2013 6:27 PM Proof 4 Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC www.euromoneyplc.com Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is a member of the FTSE 250 share index. It is a leading international business-to-business media group focused primarily on the international finance, metals and commodities sectors. The group publishes more than 70 titles in both print and online, including Euromoney, Institutional Investor and Metal Bulletin, and is a leading provider of electronic research and data under the BCA Research, Ned Davis Research and ISI Emerging Markets brands. It also runs an extensive portfolio of conferences, seminars and training courses for financial markets. The group’s main offices are in London, New York, Montreal and Hong Kong and more than a third of its revenues are derived from emerging markets. “We have continued, and will continue, to invest across the business to drive organic growth and through selective acquisitions. The five businesses acquired since the beginning of last year build on our existing strengths but also take us into exciting new sectors. First quarter trading in the new financial year is in line with the board’s expectations and sentiment in financial markets remains broadly positive. This encourages us to believe that we can continue to grow our revenues and gives us confidence that our -

Final Results Presentation Full Year Ended 30 September 2017

Final Results Presentation Full Year ended 30 September 2017 Thursday 30 November 2017 Agenda 1. Introduction Paul Zwillenberg, CEO 2. Financial Performance Tim Collier, CFO 3. Strategy Update Paul Zwillenberg, CEO 4. Q&A © 2017 DMGT 2 1 Introduction Paul Zwillenberg, CEO 3 Completion of the strategic review – good progress 1 2 3 Improving operational Increasing portfolio Enhancing financial execution focus flexibility © 2017 DMGT 4 Vision statement Confidential, for internal use only © 2017 DMGT 5 Full Year 2017 – Resilient underlying performance Group underlying revenues +1%; underlying operating profit –2% Consumer: encouraging dmg media performance B2B: mixed performance; some challenging market conditions and impairments Continued real dividend growth © 2017 DMGT 6 Real dividend growth continues 20 year CAGR: 7% 24 22.7p 22 20 18 16 14 12 10 8.5p 8 5.8p 6 4 2 0 1997 2017 Dividend Inflation FY 2017 Full Year dividend of 22.7 pence, up +3% © 2017 DMGT 7 2 Financial performance Tim Collier, CFO 8 Statutory results Pre adjustments £ million FY 2016 FY 2017 Change Revenue 1,514 1,564 +3% Operating profit 91 (129) (242%) Profit before tax 202 (112) (156%) Profit for the year 214 342 +60% Earnings per share 57.8 p 97.8 p +69% Revenue, operating profit and PBT exclude Euromoney (discontinued operations) Operating profit adversely affected by impairments of £273m Profit for the year and EPS include gain on disposals: Euromoney transaction © 2017 DMGT 9 Statutory profit to adjusted profit after tax 450 350 250 26 342 36 150 50 50 196 530 £ -

Powered by TCPDF

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) This article was downloaded by: [RMIT University] On: 15 February 2013, At: 16:12 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Soccer & Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fsas20 Football supporters and the commercialisation of football: comparative responses across Europe Peter Kennedy a & David Kennedy a School of Business for Society, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, Scotland Version of record first published: 22 Mar 2012. To cite this article: Peter Kennedy & David Kennedy (2012): Football supporters and the commercialisation of football: comparative responses across Europe, Soccer & Society, 13:3, 327-340 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2012.655503 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Q2 2013 Preqin Private Equity Benchmarks: All Private Equity Benchmark Report

Preqin Private Equity Benchmarks: All Private Equity Benchmark Report As of 30th June 2013 alternative assets. intelligent data. Preqin Private Equity Benchmarks: All Private Equity Benchmark Report As of 30th June 2013 Report Produced on 12th March 2014 This publication is not included in the CLA Licence so you must not copy any portion of it without the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. The entire contents of the report are the Copyright of Preqin Ltd. No part of this publication or any information contained in it may be copied, transmitted by any electronic means, or stored in any electronic or other data storage medium, or printed or published in any document, report or publication, without the express prior written approval of Preqin Ltd. The information presented in the report is for information purposes only and does not constitute and should not be construed as a solicitation or other offer, or recommendation to acquire or dispose of any investment or to engage in any other transaction, or as advice of any nature whatsoever. If the reader seeks advice rather than information then he should seek an independent fi nancial advisor and hereby agrees that he will not hold Preqin Ltd. responsible in law or equity for any decisions of whatever nature the reader makes or refrains from making following its use of the report. While reasonable efforts have been used to obtain information from sources that are believed to be accurate, and to confi rm the accuracy of such information wherever possible, Preqin Ltd. Does not make any representation or warranty that the information or opinions contained in the report are accurate, reliable, up-to-date or complete. -

Notice of General Meeting 2016

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own personal financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant, fund manager or other appropriate independent financial adviser who is authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 if you are in the United Kingdom, or, if not, from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all your shares in Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC, please send this document, but not the accompanying Form of Proxy, as soon as possible to the purchaser or transferee, or to the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected, for delivery to the purchaser or transferee. EUROMONEY INSTITUTIONAL INVESTOR PLC (incorporated and registered in England and Wales under number 00954730) Proposed buyback of Shares from Daily Mail and General Trust plc group – a related party transaction Notice of General Meeting This document should be read as a whole. Your attention is drawn to the letter from your Chairman which is set out on pages 1 to 7 of this document and which recommends you vote in favour of the resolutions to be proposed at the General Meeting referred to below. Notice of General Meeting of Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC to be held at 11.00am on Thursday 29 December 2016 at the offices of UBS, 5 Broadgate, London EC2M 2QS is set out at the end of this document. A Form of Proxy for use at this General Meeting is enclosed. -

Our Businesses 237 KB

Strategic Report Operating Business Reviews B2B Summary Outlook Our B2B companies operate in five sectors, namely Insurance Risk, Our B2B companies are collectively expected Property Information, Education Technology (EdTech), Energy Information, to deliver low single-digit underlying revenue Events and Exhibitions. growth in FY 2018, although revenues will be adversely affected by the disposals that have taken place in the past year and the planned disposal of EDR. In the Insurance Risk sector, 2016 RMS will continue to expand the client 2017 Pro formaΩ Movement Underlying^ Total B2B £m £m % % base for the RMS(one) software platform and associated applications, laying the Revenue# 976 899 +9% +2% groundwork for revenue acceleration Operating profit* 152 160 (5)% (15)% in FY 2019 and beyond. In the Property Operating margin* 16% 18% Information sector, the European businesses # Revenue from continuing and discontinued operations. are expected to continue to experience * Adjusted operating profit and operating margin; see pages 29 to 31 for details. relatively subdued market conditions and ^ Underlying growth rates give a like-for-like comparison; see page 31 for details. Ω Pro forma FY 2016 figures have been restated to treat Euromoney as a c.67% owned subsidiary during the first three months the remaining US businesses to continue and as a c.49% owned associate during the nine months to September 2016, consistent with the ownership profile during to deliver growth. Following the disposal FY 2017. See reconciliation on page 28. of Hobsons’ Admissions and Solutions businesses, the remaining EdTech business is expected to benefit from increased focus Euromoney of Group corporate costs, were £152 million, and to continue to deliver growth. -

Deal Flow Report 2018 Idaho

2018 IDAHO DEAL FLOW REPORT Deal Flow Report Presented by Deal Flow Opening Notes The Idaho Technology Council is pleased to present the 2018 Idaho Deal Flow Report! This is our fifth annual report, showcasing many of the companies that are starting, growing, and thriving in Idaho. The report confirms that Idaho continues to experience rapid growth and to be one of the best places in the country to do business! The data collected demonstrates the strong Idaho economy which is driving a demand for more talent and supports increased capital investment. Presenting Sponsor Hosting Sponsor In 2018, Idaho was recognized as the fastest growing state in the country. Idaho’s businesses are receiving increased attention and investment dollars from capital providers within the state and from around the country. More venture capital, private equity and angel funds are coming to Idaho to find new investment opportunities in Idaho companies. We want to recognize the many capital providers, service providers, and supporters of the Idaho entrepreneurial ecosystem, and especially the entrepreneurs and innovators who make Idaho such a great place! The most rewarding trend that we’ve seen over the last five years is the Sponsors reinvestment into the local economy by the entrepreneurs who have successful built and sold their business and used a portion of the funds to reinvest into the next generation of entrepreneurs and businesses. This trend is propelling Idaho’s growth even further and we believe it is key to Idaho’s future success. Community Venture Sponsors We would like to thank the members of this year’s Deal Flow Committee, and the various sponsors who supported our efforts, and congratulate the companies whose transactions are featured in this year’s report. -

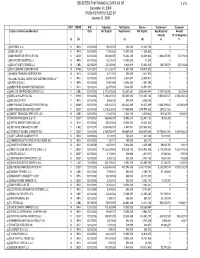

SELECTED FCM FINANCIAL DATA AS of December 31, 2008 FROM

SELECTED FCM FINANCIAL DATA AS OF 1 of 5 December 31, 2008 FROM REPORTS FILED BY January 31, 2009 B/D? DSRO A/O Adjusted Net Capital Excess Customers' Customer Futures Commission Merchant Date Net Capital Requirement Net Capital Seg Required Amount 4d(a)(2) Pt. 30 Required (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) 1 3D FOREX, LLC N NFA 12/31/2008 18,931,722 500,000 18,431,722 0 0 2 ACM USA LLC N NFA 12/31/2008 11,575,482 10,000,000 1,575,482 0 0 3 ADM INVESTOR SERVICES INC N CBOT 12/31/2008 154,941,097 74,632,265 80,308,832 1,864,327,056 72,071,646 4 ADVANCED MARKETS LLC N NFA 12/31/2008 10,071,373 10,000,000 71,373 0 0 5 ADVANTAGE FUTURES LLC N CME 12/31/2008 25,081,866 6,446,918 18,634,948 188,738,579 32,311,026 6 AIG CLEARING CORPORATION N NYME 12/31/2008 321,823,187 11,903,795 309,919,392 0 0 7 ALARON TRADING CORPORATION N NFA 12/31/2008 3,711,574 500,000 3,211,574 0 0 8 ALLIANZ GLOBAL INVESTORS DISTRIBUTORS LLC * Y NFA 12/31/2008 27,457,078 6,847,647 20,609,431 0 0 9 ALPARI (US) LLC N NFA 12/31/2008 17,497,095 10,000,000 7,497,095 0 0 10 AMERIPRISE ADVISOR SERVICES INC Y NFA 12/31/2008 22,077,618 5,346,567 16,731,051 0 0 11 BANC OF AMERICA SECURITIES LLC Y CME 12/31/2008 3,171,801,285 166,357,841 3,005,443,444 1,007,978,026 16,837,469 12 BARCLAYS CAPITAL INC Y NYME 12/31/2008 7,878,067,153 500,000,000 7,378,067,153 5,993,650,575 2,976,258,742 13 BGC SECURITIES Y NFA 12/31/2008 8,855,236 500,000 8,355,236 0 0 14 BNP PARIBAS COMMODITY FUTURES INC N NYME 12/31/2008 322,615,874 242,242,565 80,373,309 2,668,759,643 445,566,495 15 BNP PARIBAS SECURITIES -

A Big Bet on Game-Changing ADHD Treatment

20131202-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 11/27/2013 4:21 PM Page 1 CRAIN’S® NEW YORK BUSINESS VOL. XXIX, NO. 48 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM DECEMBER 2-8, 2013 PRICE: $3.00 Ice,Ice, ice,ice, maybemaybe Now-or-never vote on Bronx GOAL: Ice center CEO and hockey legend armory rink plan Mark Messier says the $275 million complex tests new norms will reap economic for development benefits for the Bronx. BY THORNTON MCENERY If there is one word in real estate circles that conveys the new poli- tics of commercial development in New York, it is Kingsbridge. The name of a long-shuttered Bronx armory, it connotes a semi- nal moment in the annals of city projects. Just as the failed Westway highway proposal of the 1970s and ’80s showed the power of environ- mentalism to kill a project, Kings- bridge did so for the cause of so- called living-wage jobs. In two weeks, almost four years to the day after a mall planned for the cavernous armory was defeat- ed by Bronx politicians, the final chapter in the Kingsbridge politi- cal saga is expected to be written. Having rejected the mall plan for See KINGSBRIDGE on Page 45 buck ennis A big bet on game-changing ADHD treatment deluxe version that will be released heart and lungs. the game,with a control group,is set Brain-to-computer interface tracks kids’ commercially for 8- to That,at least,is the idea.The chil- to begin on the Upper West Side focus; clinical study in city set to launch 12-year-olds next sum- dren, who play for 20 minutes with children at the Hallowell Cen- mer by Waltham,Mass.- three times a week,are part of ter, which specializes in treating at- based startup Atentiv. -

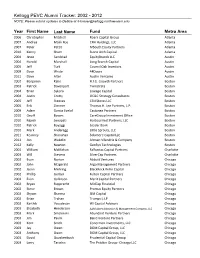

Kellogg PEVC Alumni Tracker: 2002 - 2012 NOTE: Please Submit Updates to Debbie at [email protected]

Kellogg PEVC Alumni Tracker: 2002 - 2012 NOTE: Please submit updates to Debbie at [email protected] Year First Name Last Name Fund Metro Area 2006 Christopher Mitchell Roark Capital Group Atlanta 2007 Andrea Malik Roe CRH Holdings, LLC Atlanta 2007 Peter Pettit MSouth Equity Partners Atlanta 2010 Kenny Shum Stone Arch Capital Atlanta 2004 Jesse Sandstad EquityBrands LLC Austin 2004 Harold Marshall Long Branch Capital Austin 2005 Jeff Turk Council Oak Investors Austin 2009 Dave Wride 44Doors Austin 2011 Dave Alter Austin Ventures Austin 2002 Benjamin Kahn H.I.G. Growth Partners Boston 2003 Patrick Davenport Twinstrata Boston 2004 Brian Sykora Lineage Capital Boston 2004 Justin Crotty OC&C Strategy Consultants Boston 2005 Jeff Steeves CSN Stores LLC Boston 2005 Erik Zimmer Thomas H. Lee Partners, L.P. Boston 2009 Adam Garcia Evelof Castanea Partners Boston 2010 Geoff Bowes CareGroup Investment Office Boston 2010 Rajesh Senapati HarbourVest Partners, LLC Boston 2010 Patrick Boyaggi Leader Bank Boston 2010 Mark Anderegg Little Sprouts, LLC Boston 2011 Kearney Shanahan Solamere Capital LLC Boston 2012 Jon Wakelin Altman Vilandrie & Company Boston 2012 Kelly Newton GenSyn Technologies Boston 2003 William McMahan Falfurrias Capital Partners Charlotte 2003 Will Stevens SilverCap Partners Charlotte 2002 Evan Norton Abbott Ventures Chicago 2002 John Fitzgerald Argo Management Partners Chicago 2002 Jason Mehring BlackRock Kelso Capital Chicago 2002 Phillip Gerber Fulton Capital Partners Chicago 2002 Evan Gallinson Merit Capital Partners -

Under the Bonnet Alex Savvides, JOHCM UK Dynamic Fund

December 2018 FOR PROFESSIONAL INVESTORS ONLY Under the Bonnet Alex Savvides, JOHCM UK Dynamic Fund Investment background all the headlines, no leadership challenge emerged. EU leaders went on to approve the withdrawal agreement Global equity markets generally stabilised in November, alongside a political declaration on future trade which, closing at price levels broadly similar to those at the although not binding, sets out some ambitions for the next beginning of the month. However, levels of economic round of negotiations. Despite all the political uncertainty and political uncertainty remained heightened and asset in the UK and a consensus view that Parliament would not markets remained skittish, with the Chicago Board Options vote through the agreement in its current form, sterling Exchange Volatility Index (VIX) monthly average for ended the month down just 0.2% against the euro and November little changed on October at 19.4. 0.1% down against the US dollar. Economic data continued to slow. The only bright spot was The reaction in the real economy to this heightened the JP Morgan Global Services PMI, which accelerated for uncertainty has been mixed. The UK services PMI the first time in four months – up from September’s two- showed the weakest upturn in new work since July 2016. year low – led by strengthening growth in the US. Even Meanwhile, the IHS Markit Household Finance Index this proved to be short-lived, with the subsequent flash painted a confused picture. UK households cast their US services business activity index falling to a two-month most upbeat expectation of future financial conditions low. -

Page 01 Nov 25.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Sunday 25 November 2012 11 Muharram 1434 - Volume 17 Number 5529 Price: QR2 Al Sada opens Cook and CNG fuelling Pietersen station defy India Business | 21 Sport | 32 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Khalfan trains guns on Aljazeera Kenyan arrested over Dubai police chief accuses channel of ignoring protests in Egypt murder of US woman DOHA: Known for Brotherhood- DOHA: The law-enforcement Al Sharq briefly reported yes- bashing, outspoken Dubai Police agencies here have arrested terday that an ‘African national’ Chief, Dahi Khalfan, has now a Kenyan security guard sus- suspected of killing an ‘expatri- aimed his guns at Aljazeera pected of killing an American ate’ last week had been taken TV Channel and criticised it woman who was teaching at a into custody and that he had severely for what he claimed school in Al Wakra, US-based confessed to the crime. was the Channel turning a blind newspaper, The Morning Call, Jennifer, according to The eye to Friday’s protests against reported yesterday. Morning Call, had been teach- President Mohammed Mursi in The newspaper identified ing pre-school children in her Egypt. the victim as Jennifer Brown, Al Wakra school since last Khalfan said he had lost trust a 40-year-old woman from Jim September. in Aljazeera and called on fellow Thorpe, a borough in Carbon “She was a good kid, a beauti- GCC nationals to boycott the County, Pennsylvania, and said ful girl,” her father was quoted popular Arabic Channel.