Redeveloping the Distillery District, Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partial List of Institutional Clients

Lord Cultural Resources has completed over 2500 museum planning projects in 57+ countries on 6 continents. North America Austria Turkey Israel Canada Belgium Ukraine Japan Mexico Czech Republic United Kingdom Jordan USA Estonia Korea Africa France Kuwait Egypt Central America Germany Lebanon Morocco Belize Hungary Malaysia Namibia Costa Rica Iceland Philippines Nigeria Guatemala Ireland Qatar South Africa Italy Saudi Arabia The Caribbean Tunisia Aruba Latvia Singapore Bermuda Liechtenstein Asia Taiwan Trinidad & Tobago Luxembourg Azerbaijan Thailand Poland Bahrain United Arab Emirates South America Russia Bangladesh Oceania Brazil Spain Brunei Australia Sweden China Europe New Zealand Andorra Switzerland India CLIENT LIST Delta Museum and Archives, Ladner North America The Haisla Nation, Kitamaat Village Council Kamloops Art Gallery Canada Kitimat Centennial Museum Association Maritime Museum of British Columbia, Victoria Alberta Museum at Campbell River Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism Museum of Northern British Columbia, Alberta College of Art and Design (ACAD), Calgary Prince Rupert Alberta Tourism Nanaimo Centennial Museum and Archives Alberta Foundation for the Arts North Vancouver Museum Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton Port Alberni Valley Museum Barr Colony Heritage Cultural Centre, Lloydminster Prince George Art Gallery Boreal Centre for Bird Conservation, Slave Lake National Historic Site, Port Alberni Canada West Military Museums, Calgary R.B. McLean Lumber Co. Canadian Pacific Railway, Calgary Richmond Olympic Experience -

Entuitive Credentials

CREDENTIALS SIMPLIFYING THE COMPLEX Entuitive | Credentials FIRM PROFILE TABLE OF CONTENTS Firm Profile i) The Practice 1 ii) Approach 3 iii) Better Design Through Technology 6 Services i) Structural Engineering 8 ii) Building Envelope 10 iii) Building Restoration 12 iv) Special Projects and Renovations 14 Sectors 16 i) Leadership Team 18 ii) Commercial 19 iii) Cultural 26 iv) Institutional 33 SERVICES v) Healthcare 40 vi) Residential 46 vii) Sports and Recreation 53 viii) Retail 59 ix) Hospitality 65 x) Mission Critical Facilities/Data Centres 70 xi) Transportation 76 SECTORS Image: The Bow*, Calgary, Canada FIRM PROFILE: THE PRACTICE ENTUITIVE IS A CONSULTING ENGINEERING PRACTICE WITH A VISION OF BRINGING TOGETHER ENGINEERING AND INTUITION TO ENHANCE BUILDING PERFORMANCE. We created Entuitive with an entrepreneurial spirit, a blank canvas and a new approach. Our mission was to build a consulting engineering firm that revolves around our clients’ needs. What do our clients need most? Innovative ideas. So we created a practice environment with a single overriding goal – realizing your vision through innovative performance solutions. 1 Firm Profile | Entuitive Image: Ripley’s Aquarium of Canada, Toronto, Canada BACKED BY DECADES OF EXPERIENCE AS CONSULTING ENGINEERS, WE’VE ACCOMPLISHED A GREAT DEAL TAKING DESIGN PERFORMANCE TO NEW HEIGHTS. FIRM PROFILE COMPANY FACTS The practice encompasses structural, building envelope, restoration, and special projects and renovations consulting, serving clients NUMBER OF YEARS IN BUSINESS throughout North America and internationally. 4 years. Backed by decades of experience as Consulting Engineers. We’re pushing the envelope on behalf of – and in collaboration with OFFICE LOCATIONS – our clients. They are architects, developers, building owners and CALGARY managers, and construction professionals. -

!Gotham I Gotham I Hollow' 1

HOUSES for SALE VA. (Cowt.)| | HOUSES FOR SALE—VA. HOUSiS FOR SALE—VA. | | HOUSIS FOR SAU—VA. HOUSIS FOX SAU—VA. | HOUSES FOE SAU—VA. HOUSES FOR SALE—VA. INVESTMENT PROP, FOR SALE THE EVENING STAR IRL. N., Westover area—Cape Cod ' TEN ACRES—Two-story Colonial. ARLINGTON. NORTH C-11 Liv. rm . din. rm., kit.. 3 bedrms F’our bedrms.. lge. paneled liv. rm., HOT-WATER HEAT | YOU NAME IT 31 l-BLDRM. UNITS FirfprooL Washington, D. C. •4 part fin.; bath. 2nd bath roughed fireplace, niahog.-paneled din. rm.. OPEN DAILY We ar, offering these all-brlrk I Name your own payment THE well located In nearbv Va ; 538.400 FRIDAY, MARCH S». I»#7 and end . full bsmt ; $19,509.1 lge. paneled (equip.*, screened 1 new ramblers 1 a price. I purchase down on ABOVE AVERAGE annual in pch kit. MODERN 1 reasonable the of this almost-new 3- income Owner tradintr lor J H_BENOIT. Realtor. KE.B-9H77.' lge barn with studio in loft; Features 2 flrepls.. hot-water bese-l I bedroom brick rambler in Falls SPLIT-LEVEL larser project. Will xacrlftce KEL- down, compl furn . 3-bedroom cottage, board heat, 3 lge. bedrms., full¦Church Spacious A: INDUSTRIAL PROP. FOR RENT ARI... N.; SI .000 assume shrubbery, YOU CAN’T bedrms.. living A new 49-foot brick LEY BRANNEK. DI. 7-7140: loan, payments trees, excel, fenced area ground-level bsmt., modern kit., with. room picture windows, home with eves 01. approx. SIH.OOO lor horses; Shown by Plenty i with flre- built-in garase on a 11. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Duplicity: Exploring the Many Faces of Gotham

Duplicity: Exploring the many faces of Gotham “And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughing stock or a painful embarrassment.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, Also Sprach Zarathustra The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan’s follow up to 2005’s convention- busting Batman Begins, has just broken the earlier box office record set by Spiderman 3 with a massive opening weekend haul of $158 million. While the figures say much about this franchise’s impact on the popular imagination, critical reception has also been in a rare instance overwhelmingly concurrent. What is even more telling is that the old and new opening records were both set by superhero movies. Much has already been discussed in the media about the late Heath Ledger’s brave performance and how The Dark Knight is a gritty new template for all future comic-to-movie adaptations, so we won’t go into much more of that here. Instead, let’s take a hard and fast look at absolutes and motives: old, new, black, white and a few in between. The brutality of The Dark Knight is also the brutality of America post-9/11: the inevitable conflict of idealism and reality, a frustrating political comedy of errors, and a rueful Wodehouseian reconciliation of the improbable with the impossible. Even as the film’s convoluted and always engaging plot breaks down some preconceptions about the psychology of the powerful, others are renewed (at times without logical basis) – that politicians are corruptible, that heroes are intrinsically flawed, that what you cannot readily comprehend is evil incarnate – and it isn’t always clear if this is an attempt at subtle irony or a weary concession to formula. -

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

Escale À Toronto

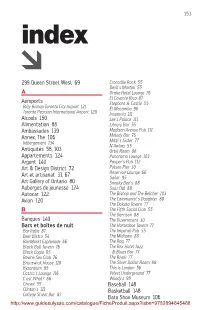

153 index 299 Queen Street West 69 Crocodile Rock 55 Devil’s Martini 55 A Drake Hotel Lounge 76 El Covento Rico 87 Aéroports Elephant & Castle 55 Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport 121 El Mocambo 96 Toronto Pearson International Airport 120 Insomnia 111 Alcools 150 Lee’s Palace 111 Alimentation 88 Library Bar 55 Ambassades 139 Madison Avenue Pub 111 Annex, The 106 Melody Bar 76 hébergement 134 Mitzi’s Sister 77 N’Awlins 55 Antiquités 58, 103 Orbit Room 88 Appartements 124 Panorama Lounge 103 Argent 140 Pauper’s Pub 112 Art & Design District 72 Polson Pier 30 Reservoir Lounge 66 Art et artisanat 31, 67 Sailor 95 Art Gallery of Ontario 80 Sneaky Dee’s 88 Auberges de jeunesse 124 Souz Dal 88 Autocar 122 The Bishop and The Belcher 103 Avion 120 The Communist’s Daughter 88 The Dakota Tavern 77 B The Fifth Social Club 55 The Garrison 88 Banques 140 The Guvernment 30 Bars et boîtes de nuit The Horseshoe Tavern 77 Bar Italia 87 The Imperial Pub 55 Beer Bistro 54 The Midtown 88 BierMarkt Esplanade 66 The Raq 77 Black Bull Tavern 76 The Rex Hotel Jazz Black Eagle 95 & Blues Bar 77 Bovine Sex Club 76 The Rivoli 77 Brunswick House 110 The Silver Dollar Room 96 Byzantium 95 This is London 56 Castro’s Lounge 116 Velvet Underground 77 C’est What? 66 Woody’s 95 Cheval 55 Baseball 148 Clinton’s 111 Basketball 148 College Street Bar 87 Bata Shoe Museum 106 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782894645468 154 Beaches International Jazz E Festival 144 Eaton Centre 48 Beaches, The 112 Edge Walk 37 Bières 150 Électricité 145 Bières, -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

Self Guided Tour

The Toronto Ghosts & Hauntings Research Society Present s… About This Document: Since early October of 1997, The Toronto Ghosts and Hauntings Research Society has been collecting Toronto’s ghostly legends and lore for our website and sharing the information with anyone with an interest in things that go bump in the night… or day… or any time, really. If it’s ghostly in nature, we try to stay on top of it. One of the more popular things for a person with a passion for all things spooky is to do a “ghost tour”… which is something that our group has never really offered and never planned to do… but it is something we get countless requests about especially during the Hallowe’en season. Although we appreciate and understand the value of a good guided ghost tour for both the theatrical qualities and for a fun story telling time and as such, we are happy to send people in Toronto to Richard Fiennes-Clinton at Muddy York Walking Tours (who offers the more theatrical tours focusing on ghosts and history, see Image Above Courtesy of Toronto Tourism www.muddyyorktours.com) We do also understand that at Hallowe’en, these types of tours can Self Guided Walking Tour of fill up quickly and leave people in the lurch. Also, there are people that cannot make time for these tours because of scheduling or other commitments. Another element to consider is that we know there are Downtown Toronto people out there who appreciate a more “DIY” (do it yourself) flavour for things… so we have developed this booklet… This is a “DIY” ghost tour… self guided… from Union Station to Bloor Street…. -

378 Yonge Street Area Details

LANDMARK CORNER OPPORTUNITY FLAGSHIP RETAIL LOCATION YONGE STREET & GERRARD STREET CORY ROSEN Goudy Real Estate Corp. VICE PRESIDENT, SALE REPRESENTATIVE Real Estate Brokerage Goudy Real Estate Corp. Real Estate Brokerage Commercial Real Estate (416) 523-7749 Sales & Leasing [email protected] 505 Hood Rd., Unit 20, Markham, ON L3R 5V6 | (905) 477-3000 The information contained herein has been provided to Goudy Real Estate Corp. by others. We do not warrant its accuracy. You are advised to independently verify the information prior to submitting an Offer and to provide for sufficient due diligence in an offer. The information contained herein may change from time to time without notice. The property may be withdrawn from the market at any time without notice. TORONTO EATON CENTRE YONGE & DUNDAS 1 YONGE STREETS RETAIL THE AURA RYERSON UNIVERSITY 378 YONGE ST. RYERSON UNIVERSITY 378 YONGE STREET AREA DETAILS Flagship retail opportunity at the corner of Yonge & Gerrard Street in the heart of Toronto. Proximity to Toronto Eaton Centre, Yonge Ryerson University is home to over 54,000 students in its various & Dundas Square, Ryerson University, and much more. 378 Yonge undergraduate, graduate and continuing education courses along Street is the point where the old Toronto meets the new Toronto - a with 3,300 faculty & staff. Ryerson University is not only expanding building designed by renowned architect John M. Lyle. but is also home to Canada’s largest undergraduate business school, the Ted Rogers School of Management. YONGE & DUNDAS THE AURA Yonge & Dundas Square and 10 Dundas is one of Toronto’s main attractions boasting open air events, a 24 multiplex theatre, 25 The Aura Condominium is Toronto’s tallest residential building, eateries, and many shops. -

Ntconf Toronto2019 Generalinf

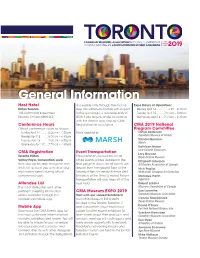

NFERENCE General Information Host Hotel accessible only through the mobile Expo Hours of Operation: Hilton Toronto app. We will forward details with respect Monday, April 14 .................................4:30 – 6:30 pm 145 Richmond Street West to the app once it is available, early in Tuesday, April 15 .....................7:00 am – 5:00 pm Toronto, Ontario M5H 2L2 2019. If you require onsite assistance Wednesday, April 16..........7:00 am – 2:30 pm with the mobile app, stop by CMA Conference Hours Registration for assistance. CMA 2019 National Official conference hours as follows: Program Committee Sunday, April 14 .......................8:00 am – 4:00 pm Kindly supported by: Tanya Anderson Canadian Museum of History Monday, April 15 .....................8:00 am – 6:30 pm Tamara Berlana Tuesday, April 16 .....................7:00 am – 5:00 pm Marsh Wednesday, April 17..........7:00 am – 4:30 pm Kathleen Brown Lord Cultural Resources CMA Registration Event Transportation Lory Drusian Toronto Hilton Transportation instructions for all Royal Ontario Museum Varley Foyer, Convention Level offsite events will be detailed in the Elizabeth Edwards Here you will be able to register and final program. Buses for all events will Art Dealers Association of Canada find staff to assist you with all of your depart from the ground floor at the Nick Foglia, registration needs during official Toronto Hilton, University Avenue West McMichael Canadian Art Collection conference hours. Entrance at the time(s) noted. Return Monique Horth transportation will also drop off at the Ingenium Attendee List host hotel. Robert Laidler The list of delegates and other Museums Foundation of Canada pertinent meeting information CMA Museum EXPO 2019 Sue Lamothe will be available through the Visit with our valued Exhibitors! Canadian Museums Association conference mobile app.