Read a Free Sample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMEÇA a CORRIDA RUMO AO OURO Alan Fonteles É Um Dos Destaques Do Time Brasil UM GUIA PARA TORCER NOS JOGOS PARALÍMPICOS Moda

QUARTA-FEIRA, 7.9.2016 CADERNO ESPECIAL Nº 1 Jornal Paralímpico COMEÇA A CORRIDA RUMO AO OURO EM COOPERAÇÃO COM Alan Fonteles é um dos destaques do Time Brasil UM GUIA PARA TORCER NOS JOGOS PARALÍMPICOS Modalidades, atletas e curiosidades da Rio-2016 2|Jornal Paralímpico|Quarta-feira 7.9.2016 ÍNDICE O PROJETO THILO RUECKEIS/TAGESSPIEGEL 3 | Editorial 6 | ‘Paratodos’ Márvio dos Anjos, editor de Documentário mostra rotina Esportes do GLOBO, Lorenz de atletas paralímpicos Maroldt, editor-chefe do jornal alemão “Tagesspiegel”, e Mariana 7 | O pesadelo de Oscar Pistorius Vieira de Mello, gerente-geral Um perfil do velocista Alan de Integração Paralímpica Fonteles, fã de Senna e Bolt do Comitê Rio-2016, celebram o espírito dos Jogos 7 | ‘Tubarão’ nas piscinas do Rio Clodoaldo Silva quer despedida DIVULGAÇÃO/CPB em casa em grande estilo 7 | Silêncio, por favor Em dois esportes, a torcida não pode fazer barulho 7 | Em constante mudança Avaliação contínua determina classe de cada atleta Conexão Brasil-Alemanha na Rio-2016 8 | Novas modalidades 4 e 5 | Guia de modalidades Canoagem e triatlo estreiam As reportagens do Jornal Paralímpico que você lê nesta edição especial foram escritas por dez jovens talentos brasileiros. Eles participaram de um concurso de redação promovido pelo jornal alemão “Der Um resumo de todos os esportes nos Jogos Rio-2016 Tagesspiegel” e foram selecionados por uma banca formada por jornalistas do GLOBO e professores paralímpicos e os principais da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). De vários estados do Brasil, os estudantes Fernan- destaques da equipe brasileira 8 | Estrelas internacionais da Lagoeiro (de 22 anos), Guilherme Longo (23), Gustavo Altman (18), Hugo L’Abbate (22), João Quatro atletas para ficar de olho Pedro Soares (22), Jorge Salhani (22), Leonardo Levatti (22), Letícia Paiva (20), Natália Belizario 6 | História e metas do Time Brasil durante a competição (20) e Thaís Contarin (22) demonstraram garra e dedicação. -

USP 2016 Team USA Announcement

2016 U.S. Paralympic Track & Field Team Nominated For Rio BY BRIANNA TAMMARO | JULY 03, 2016, 6:56 A.M. (ET) Members of the U.S. Paralympic Track & Field Team at the team naming ceremony in Charlotte, North Carolina CHARLOTTE, N.C. – U.S. Paralympics, a division of the United States Olympic Committee, announced today the 66 athletes who will represent Team USA in track & field at the 2016 Paralympic Games. The 40 men and 26 women on the roster, in addition to three guides for visually impaired athletes, will compete in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil from September 7-18. Tatyana McFadden (Clarksville, Maryland) is one of the athletes headlining the U.S. team in Rio de Janeiro. The five- time Paralympian and 11-time Paralympic medalist is aiming to become the first athlete to sweep every distance from the 100-meter to the marathon at the Paralympic Games with seven events. Highlighting the men’s side is Ray Martin (Jersey City, New Jersey) who emerged as the most decorated U.S. man on the track at the London 2012 Paralympic Games, winning gold in all four events he competed in. Returning to the roster for Rio are 14 medalists from the London Games, including Paralympic champions Jeremy Campbell (Perryton, Texas) in men’s discus F44 and Shirley Reilly (Tucson, Arizona) in the women’s marathon T54. Team USA won nine gold, six silver and 13 bronze for a total of 28 medals in London. Two athletes will be representing the United States in two sports as Allyssa Seely (Glendale, Arizona) and Grace Norman (Jamestown, Ohio) were nominated to the U.S. -

The Paralympian 2018 02|2017 1 President’S Message

OOFFICIALFFICIAL MAGAZINEMAGAZINE OOFF TTHEHE PPARALYMPICARALYMPIC MOVEMENTMOVEMENT E H ISSUE # 02 | 2017 THE T RAINING RECORDS The London 2017 World Para Athletics Championships broke records both on and off the track. NEWS FEATURE INTERVIEW Coming up, Paris 2024 Meet new IPC President Alpine skiing legend plans to and Los Angeles 2028 Andrew Parsons quit after PyeongChangTHE PARALYMPIAN 2018 02|2017 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE “Despite the busy start, I have not taken my focus off the fact that as IPC President I am responsible for leading the Governing Board in setting the strategic direction of the organisation.“ Dear friends, Next year we will start a full review of the IPC Governance Structure where the whole elcome to this edition of The of the membership and every one of our Paralympian, my fi rst as IPC constituencies, mainly the athletes, will have President. the possibility to contribute and be listened to. I must say that I left Sep- This edition of The Paralympian looks back at tember’sW IPC General Assembly excited and a busy summer of World Championships, looks honoured about being elected by the IPC ahead to upcoming Paralympic Games and membership, but also really well aware of the profi les the outstanding work that is being done tremendous responsibility I have to lead the by the NPCs of Laos and Peru. There is also ad- Paralympic Movement. vice on how to live stream a sport event and details of the latest benefi ciaries of the Agitos Under the guidance of my predecessor Sir Foundation’s Grant Support Programme. Philip Craven, the IPC and the Movement 12 experienced exponential growth. -

DICK's Sporting Goods Announces Roster of More Than 180 Team USA Contenders

NEWS RELEASE DICK'S Sporting Goods Announces Roster Of More Than 180 Team USA Contenders 1/5/2016 PITTSBURGH, Jan. 5, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- DICK'S Sporting Goods (NYSE: DKS), the ocial sporting goods retail sponsor of Team USA, announced today its roster of more than 180 U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Contenders being supported by the Company through exible employment opportunities and sponsorship agreements. To date, over 170 Contenders are currently working in 87 DICK'S Sporting Goods stores in 31 states across the country. The Contenders are oered exible work schedules and competitive compensation, allowing them to devote the necessary time to training to be part of Team USA at future Olympic or Paralympic Games. Athletes from 36 dierent sports, across both Olympic and Paralympic, summer and winter events, are participating in the program. "We're honored to provide these inspiring athletes with what they need – a exible source of income – to pursue their Olympic and Paralympic dreams," said Lauren Hobart, Executive Vice President & Chief Marketing Ocer, DICK'S Sporting Goods. "At the same time, the Contenders are able to oer our customers their expertise as elite athletes. We have had such positive feedback on the program, from the Contenders, our customers and their fellow associates. It's truly a win-win." DICK'S announced a multi-faceted partnership last February, which included the in-store employment program, sporting goods and equipment donations to the U.S. Olympic Training Centers and sponsorships to Team USA 1 hopefuls to help them pursue their Olympic and Paralympic dreams. "DICK'S Sporting Goods' commitment to America's elite athletes through their sponsorship of the USOC and the Contenders program is opening up important new pathways for athletes working to achieve their Olympic and Paralympic dreams," said Lisa Baird, USOC Chief Marketing Ocer. -

CVOTC Olympic Voice

THE UNITED STATES OLYMPIC COMMITTEE ATHLETE SPOTLIGHT. MEN’S RUGBY TEAM The Men’s USA Rugby Sevens National Team came together to win their first-ever HSBC Sevens World Series Cup trophy. The Eagles faced tough competition throughout the London Sevens tournament but ultimately were victorious in every match. The Men’s Eagles faced France, Portugal and South Africa in pool play. In the match against France, the Eagles scored three tries and a conversion to go up 17-0 in the first half. The U.S. team scored one more try and a conversion answering France’s 19 points to win the match 24-19. The Eagles then faced Portugal. The game was tied 7-7 at halftime but the Eagles were able to pull away and win 28-12. Next, the USA took on South Africa. The Eagles found themselves down 0-12 at the end of the first half but scored 21 points to win 21-12. The Eagles finished the day with a perfect 3-0 record. In the Cup Quarterfinal, the Eagles were up against Canada. Canada beat the USA 40-0 in the Glasgow Sevens tournament the weekend prior and the Eagles were looking for redemption. Madison Hughes scored early to help the Eagles up 7-0 but Canada responded with a try of their own. Perry Baker scored at the end of the first half to give the Eagles a larger lead. Maka Unufe, Garrett Bender and Carlin Isles all scored in the second half to assist in a 29-10 win for the Eagles. -

ANNOUNCEMENTS. ATHLETE SPOTLIGHT. KHATUNA Lorig

THE UNITED STATES OLYMPIC COMMITTEE ATHLETE SPOTLIGHT. Khatuna LORIG, ARCHERY Khatuna Lorig is one of the world’s most decorated and accomplished female archers. Born and raised in Tbilisi, Republic of Georgia, Khatuna took up archery in sixth grade. She found success very quickly and began competing at an elite level. At the age of 18, Lorig competed in her first Olympic Games for the Unified Team in the 1992 Barcelona Games where she won a bronze medal in the team competition. Khatuna continued to improve and competed in the 1996 Atlanta Games and 2000 Sydney Games as a member of the Republic of Georgia’s team. Lorig became a United States citizen in 2005, which allowed her to compete in the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing as a member of Team USA. She also served as the flag bearer in the Closing Ceremony. In her fifth Olympic Games, Lorig finished in fourth place, just shy of the podium at the 2012 Olympic Games in London. Lorig has a total of eight podium finishes so far in 2015 alone, and with more likely to come. She started the year off by winning bronze at the Indoor Archery World Cup Stage 4. Her first gold medal of the year came from the Arizona Cup where she also earned a bronze medal in the women’s recurve team division. She followed that tournament with another gold medal at the Easton Foundations Gator Cup. Lorig won bronze at the World Cup Stage 1 as a member of the women’s recurve team. On her home field at the CVOTC, Lorig earned a silver medal in the SoCal Showdown. -

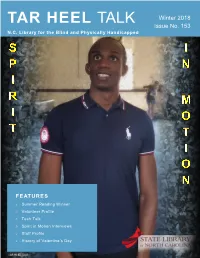

TAR HEEL TALK Winter 2018 Issue No

TAR HEEL TALK Winter 2018 Issue No. 153 N.C. Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped FE ATURES Summer Reading Winner Volunteer Profile Tech Talk Spirit in Motion Interviews Staff Profile History of Valentine’s Day TAR HEEL TALK Summer Reading Winner — Valari Rios Every Summer, our library participates in a pro- gram known across the country as Summer Reading. We hold a program for our adult and children patrons. Participants who read the most books throughout the Summer earn prizes. In to- tal, we can have up to twelve winners. The top 3 adult readers using BARD, the top 3 adult read- ers who receive their books through the mail, the top 3 children using BARD, and the top 3 children who receive books in the mail. This year, we had 60 participants in the Adult Summer Reading Program and 31 participants in the Kid’s Summer Reading Program. We were able to contact the winner of the Adult Summer Reading program, Valari Rios, and asked her about her experience in this year’s program. Tar Heel Talk is a publication of the N.C. Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NCLBPH), State Library of North Carolina, and N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. Address ……………...1841 Capital Blvd Governor …………………...Roy Cooper Raleigh, NC 27635 Secretary ……………..Susi H. Hamilton Voice …………………….(919) 733-4376 State Librarian …………....Cal Shepard Fax .…………………..….(919) 733-6910 Regional Librarian ………...Carl Keehn TDD …………………..…(919) 733-1462 Editor ………...………...…...Clint Exum Toll Free …………….….1-888-388-2460 Editorial Staff ……………..Gina Powell Email …………..……[email protected] Craig Hayward Web Page. -

5Th Loc WORLD CONFERENCE on WOMEN and SPORT

5th IOC WORLD CONFERENCE ON WOMEN AND SPORT TOGETHER STRONGER — THE FUTURE OF SPORT 5th IOC WORLD CONFERENCE ON WOMEN AND SPORT TOGETHER STronger — THE FUTURE OF SPORT 16-18 FEBRUARY 2012, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA, USA 5th IOC World Conference on Women and Sport Page 1 / 78 International Cooperation and Development Department Print Table of Contents Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. FOREWORDS . 4 1 .1 . Message from the President of the International Olympic Committee, Dr Jacques Rogge . 4 1 .2 . Message of the Chair of the IOC Women and Sport Commission, Ms Anita L . DeFrantz . 5 1 .3 . Message from the USOC President, Mr Lawrence F . Probst III . 6 2. PROGRAMME OF THE CONFERENCE . 7 3. SUMMARIES . 13 3 .1 . OPENING CEREMONY . 13 3 .2 . PLENARY 1 Leadership Views on Women in the World of Sport . 16 3 .3 . PLENARY 2 Partnerships for Progress . 20 3 .4 . DIALOGUE SESSION A Setting the Pace for a Sustainable Responsibility . 23 3 .5 . DIALOGUE SESSION B Government, Legislature and Attitudes . 27 3 .6 . DIALOGUE SESSION C Matters Medical . 30 3 .7 . DIALOGUE SESSION D Empowering Women and Girls through Education . 33 3 .8 . PLENARY 3 Role Models and Leadership . 36 3 .9 . DIALOGUE SESSION E It’s All in the Numbers . 38 3 .10 . DIALOGUE SESSION F Sport, Peace and Development . 40 3 .11 . DIALOGUE SESSION G Business of Sport . 42 3 .12 . DIALOGUE SESSION H Women, Sport and the Media . 45 3 .13 . PLENARY IV Growing Up in a Gender-Balanced Sporting Society – a Special Session for Young People by Young People . -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-8 © 2020 United States Olympic & Paralympic Museum All rights reserved. Except for educational fair use, no portion of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without explicit prior permission. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for educational use. Content created by TurnKey Education, Inc. for USOPM. TurnKey Education, Inc.: www.turnkeyeducation.net TABLE OF CONTENTS Starting Gate 2 Welcome to the United States Olympic & Paralympic Museum 3 What to Expect on Your Field Trip 4 Using this Teacher’s Guide 7 Tour of Champions: A Student Field Trip Activity 10 Journey to Excellence: STEAM Classroom Activities and Project-Based Inquiries 17 1. Global Geography: Social Studies, Fine Arts 18 2. Is Age Just a Number?: Math; Reading, Writing, & Communicating 26 3. Muscle and Mind: Math; Reading, Writing, & Communicating; Fine Arts 34 4. Ask the (Ancient Greek) Athlete: Social Studies; Reading, Writing, & Communicating 43 The Extra Mile: Additional Resources 51 When & Where: Timeline of the Modern Olympic & Paralympic Games 52 Team USA: Hall of Fame Inductees 55 Olympic Games: Puzzles & Challenges 61 Cryptogram: Voice of a Champion 62 Crossword: Paralympic Sports 63 Word Search: Host Countries 65 Beyond the Medal: Curriculum Correlations 67 National Curriculum Standards 68 Colorado Academic Standards 69 STARTING GATE USOPM TEACHER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-8 | PAGE 2 engaging. An experience that blends historic artifacts with state-of-the-art multimedia exhibits will captivate your students from start to finish. From the Opening Ceremonies to the medal podiums, your class will be part of Team USA like never before. -

Final Information and Meet Program

FINAL INFORMATION AND MEET PROGRAM Elite/University/Open Meet Information Packet Pick‐up Policy and Distribution Packets must be picked‐up and paid in full at the front of the stadium. Packets will not be allowed to remain at packet pick‐up for other coaches, managers, or athletes. The coach or athlete representative is responsible for credential and wristband distribution. Checks and cash are accepted. Please make checks payable to, MT. SAC RELAYS. If you paid online, please bring proof of payment with you. Charges presented must be paid or packets will not be provided. Facility use and Practice Times Hilmer Lodge Stadium For your convenience the stadium, runways, and throwing rings will be available with restriction. The track and runways are open for use, including use of the hurdles, blocks, and sand and landing pits. Crossbars and standards will be available at both high jump and pole vault pits. Use of shot put, discus, javelin and hammer rings will be limited to footwork and drills only. At no time will it be allowed to throw or release an implement of any kind. Boards will not be available at the long jump & triple jump runways until Thursday April 17 per the facility time schedule. Facility Schedule Dates Location Time April 16 Hilmer Lodge Stadium 10:00am‐7:00pm Hammer Facility 2:00pm‐4:00pm Lower Field 10:00am‐2:00pm, and 5:00pm‐7:00pm April 17 Hilmer Lodge Stadium 8:00am‐4:00pm Hammer Facility 12:00pm‐4:00pm Lower Field 8:00am‐2:00pm, and 5:00pm‐7:00pm April 18 & 19 All facilities will be in use and closed Athlete Check‐in Procedures Check‐in Athletes may check‐in 1.5 hours prior to the start of their event(s). -

USA Swimming Board of Directors Meeting Minutes November 21, 2015 / J.W

USA Swimming Board of Directors Meeting Minutes November 21, 2015 / J.W. Marriott LA Live 1 CALL TO ORDER 2 USA Swimming President, Jim Sheehan, called the November 21, 2015 Board of Directors 3 meeting to order at 8:00 a.m. with the following members in attendance: 4 5 PRESENT: Tim Bauer, John Bitter, John Bradley, Ben Britten, Robert Broyles, David 6 Coddington, Ed Dellert, Van Donkersgoed, Brandon Drawz, Clark Hammond, Don Heidary, 7 Stu Hixon, Margaret Hoelzer, Amy Hoppenrath, Michael Klueh, Bill Maxson, Dan McAllen, 8 John Morse, Dale Neuburger, Kelley Otto, Derek Paul, Chip Peterson, John Roy, Jim Ryan, 9 Jim Sheehan, Bruce Stratton, Ed Tsuzuki, Mary Turner, Peter Vanderkaay, Ron Van Pool, 10 Mark Weber, Garrett Weber-Gale, Carol Zaleski. 11 12 NOT PRESENT: Tim Liebhold, Aaron Peirsol, Jim Wood. Marie Scovron joined the meeting 13 via conference call. 14 15 MOMENT OF SILENCE 16 A moment of silence was observed for USA Swimming members who have passed away 17 since the last USA Swimming Board of Directors meeting. 18 19 AGENDA REVIEW 20 The following item was added to the Agenda (Attachment 1): 21 ACTION / DISCUSSION ITEMS: Reliable Hearsay Task Force Report 22 23 CONFLICT OF INTEREST 24 “Is any member aware of any conflict of interest (that is, of a personal interest or direct or 25 indirect pecuniary interest) in any matter being considered by this meeting which should now 26 be reported or disclosed or addressed under the USA Swimming Conflict of Interest Policy?” 27 28 If a Board member determines there to be a conflict of interest at any point during the 29 course of the meeting when a specific subject is being discussed and / or action is being 30 taken, a declaration of a conflict of interest should be made at that time. -

US Wheelchair Racer's Bid for 7 Golds Falls Short

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2016 SPORTS Paralympics: Podiums of the day RIO DE JANEIRO: Rio de Janeiro 2016 Summer Paralympics podiums on Friday: ATHLETICS JUDO 66 - 73kg (lightweight) 100m - T13 Gold: Ramil Gasimov (AZE) Gold: Jason Smyth (IRL) Silver: Dmytro Solovey (UKR) Silver: Johannes Nambala (NAM) Bronze: Nikolai Kornhass (GER) Bronze: Chad Perris (AUS) Bronze: Feruz Sayidov (UZB) 100m - T53 73 - 81kg (half-middleweight) Gold: Brent Lakatos (CAN) Gold: Eduardo Adrian Avila Sanchez (MEX) Silver: Pongsakorn Paeyo (THA) Silver: Lee Jung-Min (KOR) Bronze: Li Huzhao (CHN) Bronze: Rovshan Safarov (AZE) Bronze: Oleksandr Kosinov (UKR) 400m - T12 Gold: Sun Qichao (CHN) 52 - 57kg (lightweight) Silver: Mahdi Afri (MOR) Gold: Inna Cherniak (UKR) Bronze: Luis Goncalves (POR) Silver: Lucia Da Silva Teixeira Araujo (BRA) Bronze: Junko Hirose (JPN) 100m - T35 Bronze: Seo Ha-Na (KOR) Gold: Ihor Tsvietov (UKR) Silver: Fabio Da Silva Bordignon (BRA) 57 - 63kg (half-middleweight) Bronze: Hernan Barreto (ARG) Gold: Dalidaivis Rodriguez (CUB) Silver: Iryna Husieva (UKR) 100 m - T43/44 Bronze: Jin Song-Lee (KOR) Gold: Jonnie Peacock (GBR) Bronze: Tursunpashsha Nurmetova (UZB) Silver: Liam Malone (NZL) Bronze: Felix Streng (GER) POWERLIFTING 54 kg Gold: Roland Ezuruike (NGR) 400 m - T20 Silver: Wang Jian (CHN) Gold: Daniel Martins (BRA) Bronze: Dimitrios Bakochristos (GRE) Silver: Luis Arturo Paiva (VEN) Bronze: Gracelino Tavares Barbosa (CPV) 59 kg Gold: Sherif Osman (EGY) HAUTEUR - T42 Silver: Ali Jawad (GBR) Gold: Mariyappan Thangavelu (IND) Bronze: Yang