Spatial Distance and Climate Determine Modularity in a Cross-Biomes Plant–Hummingbird Interaction Network in Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change Th

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero 02 05 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 1) 03 11 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 2) 04 18 Split Garnet-throated Hummingbird Lamprolaima rhami 05 22 Recognize Amazilia alfaroana as a species not of hybrid origin, thus moving it from Appendix 2 to the main list 06 26 Change the linear sequence of species in the genus Dendrortyx 07 28 Make two changes concerning Starnoenas cyanocephala: (a) assign it to the new monotypic subfamily Starnoenadinae, and (b) change the English name to Blue- headed Partridge-Dove 08 32 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 09 36 Split Royal Tern Thalasseus maximus into two species 10 39 Recognize Great White Heron Ardea occidentalis as a species 11 41 Change the English name of Checker-throated Antwren Epinecrophylla fulviventris to Checker-throated Stipplethroat 12 42 Modify the linear sequence of species in the Phalacrocoracidae 13 49 Modify various linear sequences to reflect new phylogenetic data 1 2020-A-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 532 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero Background: “Warbler” is perhaps the most widely used catch-all designation for passerines. Its use as a meaningful taxonomic indicator has been defunct for well over a century, as the “warblers” encompass hundreds of thin-billed, insectivorous passerines across more than a dozen families worldwide. This is not itself an issue, as many other passerine names (flycatcher, tanager, sparrow, etc.) share this common name “polyphyly”, and conventions or modifiers are widely used to designate and separate families that include multiple groups. -

Observations on a Nest of Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes Scutatus

Observations on a nest of Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes scutatus Marcelo Ferreira de Vasconcelos, Prinscila Neves Vasconcelos and Geraldo Wilson Fernandes Cotinga 16 (2001): 53–57 Foram feitas observações em um ninho do beija-flor-de-gravata-verde Augastes scutatus em uma localidade de campo rupestre na Serra do Cipó, Minas Gerais. Apenas uma fêmea desta espécie foi observada cuidando dos ninhegos. Durante as observações foram registrados ataques de um indivíduo de beija-flor-tesoura Eupetomena macroura ao ninho de A. scutatus. Pela primeira vez são descritos os comportamentos de cuidado parental e a evolução da plumagem do ninhego de A. scutatus. Introduction Life histories of the endemic bird species of the Espinhaço range in south-east Brazil (Endemic Bird Area 07315) are poorly known, with some exceptions2,4,6,7,8,9,16–19. Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes scutatus, a near-threatened species1, is restricted to campos rupestres of the Espinhaço10,11,13–15. Apart from a description of the nest4,5,9,11, virtually nothing is known of its breeding biology. This paper describes observations at a nest of this little-known hummingbird. Material and methods Observations were undertaken on 23, 26 and 29 June and 3, 6, 9, 11 and 16 July 1999, totalling 37 hours. The nest was watched with 8 x 40 binoculars from a distance of 12 m. Activity was described in a notebook. Furthermore, we filmed and photographed all behaviours which occurred at a distance of 4 m or less from the nest. We did not measure the nestlings to avoid stress to the birds. -

Aves:Trochilidae) E Passeriformes

EFEITO DA INTRODUÇÃO DE BEBEDOUROS ARTIFICIAIS NA PARTIÇÃO DE NICHO ENTRE APODIFORMES (AVES:TROCHILIDAE) E PASSERIFORMES. JOVÂNIA GONÇALVES TEIXEIRA¹, MARIANA ABRAHÃO ASSUNÇÃO¹, CELINE DE MELO ². RESUMO: Aves das ordens Apodiformes e Passeriformes representam grupos de alta importância ecológica, sendo dominantes nas interações aves-flores na região Neotropical. Entretanto, pouco se conhece sobre as relações inter-específicas envolvendo aves dessas duas ordens em ambientes urbanos. Para avaliar o efeito do aumento induzido da disponibilidade de recurso para Apodiformes (beija-flores) e Passeriformes, foi realizado um estudo experimental utilizando bebedouros artificiais contendo soluções de sacarose à 10% e à 20% de concentração, que foram oferecidos ad libitum sense a espécies presentes em duas áreas ajardinadas na cidade de Uberlândia, MG. Seis bebedouros foram distribuídos em cada área, três contendo solução à 10% e outros três à 20%. Foram realizadas 20 horas de observação em cada área, totalizando 40 horas. As espécies de beija-flores identificadas nas áreas de estudo foram Eupetomena macroura, Chlorostilbon aureoventris e Amazilia fimbriata e as espécies Passeriformes foram Molothrus bonariensis, Myiozetetes similis, Todirostrum cinereum, Vireo olivaceus e Coereba flaveola. O pico de visitação das aves aos bebedouros ocorreu no início da manhã e início da tarde. Passeriformes e beija-flores diferiram significativamente na exploração, sendo que beija-flores preferiram bebedouros com soluções menos concentradas e Passeriformes, aqueles com soluções mais concentradas. Tendo em vista a sobreposição temporal na exploração do recurso e a segregação no uso de concentrações distintas, sugere-se que Apodiformes (Trochilidae) e Passeriformes possam estar realizando partição de nicho como estratégia para minimizar a competição. -

ZOOCIÊNCIAS 9(2): 193-198, Dezembro 2007

Hummingbird pollination in Schwartzia adamantium .193 ISSN 1517-6770 Revista Brasileira de ZOOCIÊNCIAS 9(2): 193-198, dezembro 2007 Hummingbird pollination in Schwartzia adamantium (Marcgraviaceae) in an area of Brazilian Savanna Rafael Arruda1,2, Jania Cabrelli Salles1 & Paulo Eugênio de Oliveira1 1Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, 38400-902, CP 593, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil 2Present address and corresponding author: Coordenação de Pesquisas em Ecologia, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, 69011-970, CP 478, Manaus, AM, Brazil. [email protected] Abstract. Some authors have suggested that, in bird-pollinated species of Marcgraviaceae, perching birds are more adequate pollinators than hovering birds, due to the inflorescence structure and floral biology. In this study, we report territorial behavior of the swallow-tailed hummingbird Eupetomena macroura in Schwartzia adamantium. We analyzed the time spent in foraging behavior and territorial defense by the hummingbird, and the nectar availability of S. adamantium. The hummingbird spent almost 96% of the time perching. We registered 97 invasions of the territory always by others hummingbirds. During the observation period, no perching birds visited S. adamantium. Nectar volume varied from 15.0 to 114.0 µL, and sugar concentration varied from 5.5 to 27.1%. Despite that hummingbirds possibly play a minor role in the reproduction of ornithophilous Marcgraviaceae species, and occasionally touched the anthers and/or stigma, our observations suggest that it’s only responsible for fruit set of S. adamantium in PESCAN. Key words: Bird pollination, vertebrate-plant interactions, nectar energy content, resource defense, protandry, Eupetomena macroura, Trochilidae. Resumo: Alguns autores sugeriram que por causa da estrutura da inflorescência e biologia floral, aves que pousam na inflorescência são polinizadores mais adequados de espécies de Marcgraviaceae do que beija-flores. -

Body Mass As a Supertrait Linked to Abundance and Behavioral Dominance in Hummingbirds: a Phylogenetic Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aberdeen University Research Archive Received: 7 July 2018 | Revised: 17 October 2018 | Accepted: 8 November 2018 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.4785 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Body mass as a supertrait linked to abundance and behavioral dominance in hummingbirds: A phylogenetic approach Rafael Bribiesca1,2 | Leonel Herrera‐Alsina3 | Eduardo Ruiz‐Sanchez4 | Luis A. Sánchez‐González5 | Jorge E. Schondube2 1Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Unidad de Posgrado, Coordinación del Posgrado en Abstract Ciencias Biológicas, UNAM, Mexico City, Body mass has been considered one of the most critical organismal traits, and its role Mexico in many ecological processes has been widely studied. In hummingbirds, body mass 2Instituto de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad, Universidad Nacional has been linked to ecological features such as foraging performance, metabolic rates, Autónoma de México, Morelia, Mexico and cost of flying, among others. We used an evolutionary approach to test whether 3University of Groningen, Groningen, The body mass is a good predictor of two of the main ecological features of humming‐ Netherlands 4Departamento de Botánica y Zoología, birds: their abundances and behavioral dominance. To determine whether a species Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y was abundant and/or behaviorally dominant, we used information from the literature Agropecuarias, Universidad de Guadalajara, Zapopan, México on 249 hummingbird species. For abundance, we classified a species as “plentiful” if 5Museo de Zoología “Alfonso L. Herrera”, it was described as the most abundant species in at least part of its geographic distri‐ Depto. de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de bution, while we deemed a species to be “behaviorally dominant” when it was de‐ Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, México scribed as pugnacious (notably aggressive). -

A New Methodology to Use Color Spectral Data for Taxonomic, Phylogenetic, and Biogeographic Studies

A new methodology to use color spectral data for taxonomic, phylogenetic, and biogeographic studies. An example with three genera of lowland hummingbirds: Topaza, Anthracothorax, and Eulampis. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Angela Schmitz Ornés aus München Bonn 2004 ii Angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. K.-L.Schuchmann 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. W. Böhme Tag der Promotion: Diese Dissertation ist auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni- bonn.de/diss_online elektronisch publiziert iii Dedico este trabajo a mi hija ANDREA CAROLINA por ser mi motor de vida y fuente de inspiración ... iv Contents • Introduction …………………………………………………………………………….1 o Phylogenetic, systematic, and taxonomic bird studies …………………………3 o Hummingbirds: phylogeny and origin ….……………………………………..5 o Characteristics and distribution of the study taxa …...………….……………...7 o Research goals and structure of the study ……………………………………...9 • General methodology …………………………………………………………………13 o Specimens included in the study ……………………………………………...13 o Mappings ……………………………………………………………………...16 o Morphometric data ……………………………………………………………16 o Color measurements (spectral data) …………………………………………..16 o Data analyses …………………………………………………………………19 o Definition of preliminary pools for analysis ………………………………….20 • Methodology -

NESTING BEHAVIOR of the SWALLOW-TAILED HUMMINGBIRD, Eupetomena Macroura (TROCHILIDAE, AVES)

NESTING OF Eupetomena macroura 655 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF THE SWALLOW-TAILED HUMMINGBIRD, Eupetomena macroura (TROCHILIDAE, AVES) ONIKI, Y. and WILLIS, E. O. Departamento de Zoologia, Unesp, CEP 13506-900, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil Correspondence to: Yoshika Oniki, Departamento de Zoologia, Unesp, CEP 13506-900, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil, e-mail: [email protected] Received May 3, 1999 – Accepted March 16, 2000 – Distributed November 30, 2000 (With 5 figures) ABSTRACT An August or winter nestling of Eupetomena macroura was fed only every 40-50 min for at least 24 days in the nest, with fewer feedings at midday. As in other hummingbirds, it was brooded only the first week or two, and left alone even on cool nights after 12 days, probably due to the small nest size. The female attacked birds of many non-nectarivore species near the nest, in part probably to avoid predation. Botfly parasitism was extremely high, as in some other forest-edge birds. Key words: nesting, hummingbird, Eupetomena macroura, parasitism, predation. RESUMO Comportamento reprodutivo do beija-flor-tesoura, Eupetomena macroura (Trochilidae, Aves) Um jovem, de agosto ou inverno, de Eupetomena macroura foi alimentado somente a cada 40-50 min., com menos alimentações no meio do dia. Ficou, pelo menos, 24 dias no ninho. Como em outros beija- flores, a fêmea permaneceu no ninho à noite somente na primeira ou segunda semana e deixou o jovem sozinho mesmo em noites mais frias após 12 dias, provavelmente devido ao tamanho pequeno do ninho. A fêmea atacou aves de muitas espécies não-nectarívoras nas proximidades do ninho, em parte pro- vavelmente para evitar a predação. -

Amazilias.Pdf

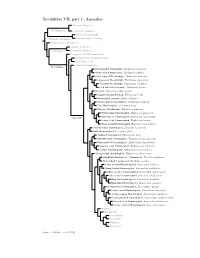

Trochilidae VII, part 1: Amazilias Topazini: Topazes Florisuginae Florisugini: Jacobins Eutoxerini: Sicklebills Phaethornithinae Phaethornithini: Hermits Polytminae: Mangoes Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Tro chilinae Bronze-tailed Plumeleteer, Chalybura urochrysia White-vented Plumeleteer, Chalybura buffonii Violet-capped Woodnymph, Thalurania glaucopis Long-tailed Woodnymph, Thalurania watertonii Crowned Woodnymph, Thalurania colombica Fork-tailed Woodnymph, Thalurania furcata Snowcap, Microchera albocoronata Coppery-headed Emerald, Elvira cupreiceps White-tailed Emerald, Elvira chionura Violet-capped Hummingbird, Goldmania violiceps Pirre Hummingbird, Goethalsia bella Mexican Woodnymph, Eupherusa ridgwayi White-tailed Hummingbird, Eupherusa poliocerca Blue-capped Hummingbird, Eupherusa cyanophrys Trochilini Stripe-tailed Hummingbird, Eupherusa eximia Black-bellied Hummingbird, Eupherusa nigriventris Scaly-breasted Hummingbird, Phaeochroa cuvierii Buffy Hummingbird, Leucippus fallax Tumbes Hummingbird, Thaumasius baeri Spot-throated Hummingbird, Thaumasius taczanowskii Many-spotted Hummingbird, Taphrospilus hypostictus Swallow-tailed Hummingbird, Eupetomena macroura Sombre Hummingbird, Aphantochroa cirrochloris Olive-spotted Hummingbird, Talaphorus chlorocercus Red-billed Streamertail / Streamertail, Trochilus polytmus Black-billed Streamertail, Trochilus scitulus Violet-crowned Hummingbird, Saucerottia violiceps Green-fronted -

Behaviourally Driven Gene Expression Reveals Song Nuclei in Hummingbird

letters to nature Two cautionary points, one perhaps encouraging and another less 2. Wagner, G. P., Chiu, C. & Hansen, T. F. Is Hsp90 a regulator of evolvability? J. Exp. Zool. 285, 116±118 so, emerge from our study. First, it is evident that a high mutation (1999). 3. Holland, J. et al. Rapid evolution of RNA genomes. Science 215, 1577±1585 (1982). rate is not always bene®cial. The adaptive neighbourhood of an 4. Domingo, E. & Holland, J. J. in The Evolutionary Biology of Viruses (ed. Morse, S. S.) 161±184 (Raven, adaptive peak can constrain evolvability, despite a high mutation New York, 1994). rate. A high rate can lead to a high mutational load, as seen during 5. Fraile, A. et al. A century of tobramovirus evolution in an Australian population of Nicotiana glauca. J. Virol. 71, 8316±8320 (1997). the evolution by clone B. Thus, evolutionary changes in a popula- 6. Chao, L. Evolution of sex and the molecular clock in RNA viruses. Gene 205, 301±308 (1997). tion of RNA viruses, whether under clinical treatment or otherwise, 7. Burch, C. L. & Chao, L. Evolution by small steps and rugged landscapes in the RNA virus f6. Genetics should not automatically be interpreted as adaptive to the virus. 151, 921±927 (1999). Second, as had already been noted12, if multiple peaks exist, a shift to 8. Fenster, C. B, Galloway, L. F. & Chao, L. Epistasis and its consequences for the evolution of natural populations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 12, 282±286 (1997). a new adaptive peak can be triggered by a costly resistance mutation 9. -

N&MA Classification Committee: Proposals 2011-A

N&MA Classification Committee: Proposals 2011-A No. Page Title 01 2 Set a minimum standard for the designation of a holotype for extant avian species 02 4 Change linear sequence of genera in Trochilidae to reflect recent genetic data 03 11 A new generic name for some sparrows formerly placed in Amphispiza 04 12 Split Gray Hawk Buteo nitidus into two species 05 16 Transfer Deltarhynchus flammulatus to Ramphotrigon 06 18 Change the gender ending of two species names 07 19 Change English Name of the Bahama Warbler to Pinelands Warbler 08 21 Reorganize classification of Thryothorus wrens 09 24 Recognize the genus Dendroplex Swainson 1827 (Dendrocolaptidae) as valid 10 27 Change sequence of wren genera 11 30 Transfer the genus Paroaria to the Thraupidae 12 32 Change species limits in the Arremon torquatus complex 13 34 Change English name of Maui Parrotbill to Hawaiian name Kiwikiu 14 36 Revise the citation for Anser anser 15 38 Move Veniliornis fumigatus to Picoides 2011-A-1formerly 2010-C-15) N&MA Classification Committee Set a minimum standard for the designation of a holotype for extant avian species The ICZN states: A holotype is the single specimen upon which a new nominal species- group taxon is based in the original publication. And subsequently recommends: Recommendation 73A. Designation of holotype. An author who establishes a new nominal species-group taxon should designate its holotype in a way that will facilitate its subsequent recognition. Recommendation 73B. Preference for specimens studied by author. An author should designate as holotype a specimen actually studied by him or her, not a specimen known to the author only from descriptions or illustrations in the literature. -

North and Middle America Proposal Set 2014-A, 25-26

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero 02 05 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 1) 03 11 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 2) 04 18 Split Garnet-throated Hummingbird Lamprolaima rhami 05 22 Recognize Amazilia alfaroana as a species not of hybrid origin, thus moving it from Appendix 2 to the main list 06 26 Change the linear sequence of species in the genus Dendrortyx 07 28 Make two changes concerning Starnoenas cyanocephala: (a) assign it to the new monotypic subfamily Starnoenadinae, and (b) change the English name to Blue- headed Partridge-Dove 08 32 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 09 36 Split Royal Tern Thalasseus maximus into two species 10 39 Recognize Great White Heron Ardea occidentalis as a species 11 41 Change the English name of Checker-throated Antwren Epinecrophylla fulviventris to Checker-throated Stipplethroat 12 42 Modify the linear sequence of species in the Phalacrocoracidae 13 49 Modify various linear sequences to reflect new phylogenetic data 1 2020-A-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 532 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero Background: “Warbler” is perhaps the most widely used catch-all designation for passerines. Its use as a meaningful taxonomic indicator has been defunct for well over a century, as the “warblers” encompass hundreds of thin-billed, insectivorous passerines across more than a dozen families worldwide. This is not itself an issue, as many other passerine names (flycatcher, tanager, sparrow, etc.) share this common name “polyphyly”, and conventions or modifiers are widely used to designate and separate families that include multiple groups. -

Crawford H. Greenewalt Papers 2010.010 Finding Aid Prepared by Laurie Rizzo and Eric Rosenzweig

Crawford H. Greenewalt papers 2010.010 Finding aid prepared by Laurie Rizzo and Eric Rosenzweig. Last updated on December 11, 2012. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia Crawford H. Greenewalt papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 Manuscripts/writings/publications......................................................................................................... 10 Photographs, proofs and contact sheets...............................................................................................