Behaviourally Driven Gene Expression Reveals Song Nuclei in Hummingbird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change Th

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero 02 05 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 1) 03 11 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 2) 04 18 Split Garnet-throated Hummingbird Lamprolaima rhami 05 22 Recognize Amazilia alfaroana as a species not of hybrid origin, thus moving it from Appendix 2 to the main list 06 26 Change the linear sequence of species in the genus Dendrortyx 07 28 Make two changes concerning Starnoenas cyanocephala: (a) assign it to the new monotypic subfamily Starnoenadinae, and (b) change the English name to Blue- headed Partridge-Dove 08 32 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 09 36 Split Royal Tern Thalasseus maximus into two species 10 39 Recognize Great White Heron Ardea occidentalis as a species 11 41 Change the English name of Checker-throated Antwren Epinecrophylla fulviventris to Checker-throated Stipplethroat 12 42 Modify the linear sequence of species in the Phalacrocoracidae 13 49 Modify various linear sequences to reflect new phylogenetic data 1 2020-A-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 532 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero Background: “Warbler” is perhaps the most widely used catch-all designation for passerines. Its use as a meaningful taxonomic indicator has been defunct for well over a century, as the “warblers” encompass hundreds of thin-billed, insectivorous passerines across more than a dozen families worldwide. This is not itself an issue, as many other passerine names (flycatcher, tanager, sparrow, etc.) share this common name “polyphyly”, and conventions or modifiers are widely used to designate and separate families that include multiple groups. -

Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden Using Native Plants

United States Department of Agriculture Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden Using Native Plants Black-chinned Hummingbird feeding on mountain larkspur, fireweed, and wild bergamot (clockwise from top) Forest National Publication April Service Headquarters Number FS-1046 2015 Hummingbird garden guide Many of us enjoy the beauty of flowers in our backyard and community gardens. Growing native plants adds important habitat for hummingbirds and other wildlife—especially pollinators. Even small backyard gardens can make a difference. Gardening connects us to nature and helps us better understand how nature works. This guide will help you create a hummingbird- What do hummingbirds, friendly garden. butterflies, and bees have in common? They all pollinate flowering plants. Broad-tailed Hummingbird feeding on scarlet gilia Hummingbirds are Why use native plants in restricted to the Americas with more your garden? than 325 species of Hummingbirds have evolved with hummingbirds in North, Central, and native plants, which are best adapted South America. to local growing seasons, climate, and soil. They prefer large, tubular flowers that are often (but not always) red in color. In this guide, we feature seven hummingbirds that breed in the United States. For each one, we also highlight two native plants found in its breeding range. These native plants are easy to grow, need little water once established, and offer hummingbirds abundant nectar. 2 Hummingbirds and pollination Ruby-throated Hummingbird feeding on the At rest, a hummer’s nectar and pollen heart beats an of blueberry flowers average of 480 beats per minute. On cold nights, it goes into What is pollination? torpor (hibernation- like state), and its Pollination is the process of moving pollen heart rate drops to (male gamete) from one flower to the ovary of another 45 to 180 beats per minute. -

Paper Describing Hummingbird-Sized Dinosaur Retracted 24 July 2020, by Bob Yirka

Paper describing hummingbird-sized dinosaur retracted 24 July 2020, by Bob Yirka teeth. Some in the field were so sure that it was a lizard and not a dinosaur that they wrote and uploaded a paper to the bioRxiv preprint server outlining their concerns. The authors of the paper then published a response addressing their concerns and refuting the skeptics' arguments. That was followed by another team reporting that they had found a similar fossil and after studying it, had deemed it to be a lizard. In reviewing both the paper and the evidence presented by others in the field, the editors at Nature chose to retract the paper. A CT scan of the skull of Oculudentavis by LI Gang, The researchers who published the original paper Oculudentavis means eye-tooth-bird, so named for its appear to be divided on their assessment of the distinctive features. Credit: Lars Schmitz retraction, with some insisting there was no reason for the paper to be retracted and others acknowledging that they had made a mistake when they classified their find as a dinosaur. In either The journal Nature has issued a retraction for a case, all of the researchers agree that the work paper it published March 11th called they did on the fossil was valid and thus the paper "Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous could be used as a source by others in the future—it period of Myanmar." The editorial staff was alerted is only the classification of the find that has been to a possible misclassification of the fossil put in doubt. -

Spider Webs and Windows As Potentially Important Sources of Hummingbird Mortality

J. Field Ornithol., 68(1):98--101 SPIDER WEBS AND WINDOWS AS POTENTIAIJJY IMPORTANT SOURCES OF HUMMINGBIRD MORTALITY DEVON L. G•nqAM Departmentof Biology Universityof Miami PO. Box 249118 Coral Gables,Florida, 33124 USA Abstract.--Sourcesof mortality for adult hummingbirdsare varied, but most reports are of starvationand predation by vertebrates.This paper reportstwo potentiallyimportant sources of mortality for tropical hermit hummingbirds,entanglement in spiderwebs and impacts with windows.Three instancesof hermit hummingbirds(Phaethornis spp.) tangled in webs of the spider Nephila clavipesin Costa Rica are reported. The placement of webs of these spidersin sitesfavored by hermit hummingbirdssuggests that entanglementmay occur reg- ularly. Observationsat buildingsalso suggest that traplining hermit hummingbirdsmay be more likely to die from strikingwindows than other hummingbirds.Window kills may need to be consideredfor studiesof populationsof hummingbirdslocated near buildings. TELAS DE ARAI•A Y VENTANAS COMO FUENTES POTENCIALES DE MORTALIDAD PARA ZUMBADORES Sinopsis.--Lasfuentes de mortalidad para zumbadoresson variadas.Pero la mayoria de los informes se circunscribena inanicitn y a depredacitn pot parte de vertebrados.En este trabajo se informan dos importantesfuentes de mortalidad para zumbadorestropicales (Phaethornisspp.) como los impactoscontra ventanasy el enredarsecon tela de arafia. Se informan tres casosde zumbadoresenredados con tela de la arafia Nephila clavipesen Costa Rica. La construccitn de las telas de arafia en lugares -

For Whom the Bird Sings: Context-Dependent Gene Expression

Neuron, Vol. 21, 775±788, October, 1998, Copyright 1998 by Cell Press For Whom The Bird Sings: Context-Dependent Gene Expression Erich D. Jarvis,* Constance Scharff, more motifs per bout, and that each motif is delivered Matthew R. Grossman, Joana A. Ramos, slightly faster (by 10±40 ms) than undirected song (Fig- and Fernando Nottebohm ure 1A; Sossinka and BoÈ hner, 1980; Bischof et al., 1981; Laboratory of Animal Behavior Caryl, 1981). The two behaviors also differ in hormone The Rockefeller University sensitivity: the amount of directed song increases with New York, New York 10021 estrogen treatment, undirected with testosterone (ProÈ ve 1974; Arnold, 1975b; Harding et al., 1983; Walters et al., 1991). Summary Though no separate neural circuits for directed and undirected song have been described, a great deal is Male zebra finches display two song behaviors: di- known about the brain circuits that mediate song acqui- rected and undirected singing. The two differ little in sition and production. Referred to collectively as ªthe the vocalizations produced but greatly in how song is song system,º these circuits consist in male zebra delivered. ªDirectedº song is usually accompanied by finches of a posterior motor pathway necessary for song a courtship dance and is addressed almost exclusively production and an anterior pathway necessary for song to females. ªUndirectedº song is not accompanied by acquisition. Both pathways originate in the high vocal the dance and is produced when the male is in the center (HVC) of the neostriatum. In the posterior pathway presence of other males, alone, or outside a nest occu- (Figure 1B, black arrows), neurons of one cell type in pied by its mate. -

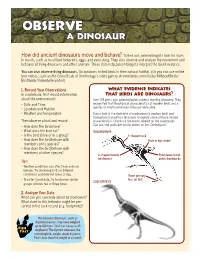

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Hummingbird Haven Backyard Habitat for Wildlife

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hummingbird Haven Backyard Habitat for Wildlife From late March through mid November, if you and then spending their winters in Mexico. look carefully, you may find a small flying Beating their wings 2.7 million times, the jewel in your backyard. The ruby-throated ruby-throated hummingbird flies 500 miles hummingbird may be seen zipping by your nonstop across the Gulf of Mexico during porch or flitting about your flower migration. This trip averages 18-20 hours garden. Inquisitive by nature, these but with a strong tail wind, the flight takes tiny birds will fly close to investigate ten hours. To survive, migrating hummers your colorful blouse or red baseball cap. must store fat and fuel up before and right The hummingbird, like many species of after crossing the Gulf—there are no wildlife is plagued by loss of habitat. sources of nectar over the ocean! However, by providing suitable backyard habitat you can help this flying jewel of a bird. Hummingbird Flowers Flowers Height Color Bloom time Hummingbird Habitat A successful backyard haven for hummingbirds contains a Herbaceous Plants variety of flowering plants including tall and medium trees, Bee Balm 2-4' W, P, R, L summer shrubs, vines, perennial and annual flowers. Flowering plants Blazing Star 2-6' L summer & fall provide hummers with nectar for energy and insects for Cardinal Flower 2-5' R summer protein. Trees and shrubs provide vertical structure for nesting, perching and shelter. No matter what size garden, try Columbine 1-4' all spring & summer to select a variety of plants to ensure flowering from spring Coral Bells 6-12" W, P, R spring through fall. -

Observations on a Nest of Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes Scutatus

Observations on a nest of Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes scutatus Marcelo Ferreira de Vasconcelos, Prinscila Neves Vasconcelos and Geraldo Wilson Fernandes Cotinga 16 (2001): 53–57 Foram feitas observações em um ninho do beija-flor-de-gravata-verde Augastes scutatus em uma localidade de campo rupestre na Serra do Cipó, Minas Gerais. Apenas uma fêmea desta espécie foi observada cuidando dos ninhegos. Durante as observações foram registrados ataques de um indivíduo de beija-flor-tesoura Eupetomena macroura ao ninho de A. scutatus. Pela primeira vez são descritos os comportamentos de cuidado parental e a evolução da plumagem do ninhego de A. scutatus. Introduction Life histories of the endemic bird species of the Espinhaço range in south-east Brazil (Endemic Bird Area 07315) are poorly known, with some exceptions2,4,6,7,8,9,16–19. Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes scutatus, a near-threatened species1, is restricted to campos rupestres of the Espinhaço10,11,13–15. Apart from a description of the nest4,5,9,11, virtually nothing is known of its breeding biology. This paper describes observations at a nest of this little-known hummingbird. Material and methods Observations were undertaken on 23, 26 and 29 June and 3, 6, 9, 11 and 16 July 1999, totalling 37 hours. The nest was watched with 8 x 40 binoculars from a distance of 12 m. Activity was described in a notebook. Furthermore, we filmed and photographed all behaviours which occurred at a distance of 4 m or less from the nest. We did not measure the nestlings to avoid stress to the birds. -

Aves:Trochilidae) E Passeriformes

EFEITO DA INTRODUÇÃO DE BEBEDOUROS ARTIFICIAIS NA PARTIÇÃO DE NICHO ENTRE APODIFORMES (AVES:TROCHILIDAE) E PASSERIFORMES. JOVÂNIA GONÇALVES TEIXEIRA¹, MARIANA ABRAHÃO ASSUNÇÃO¹, CELINE DE MELO ². RESUMO: Aves das ordens Apodiformes e Passeriformes representam grupos de alta importância ecológica, sendo dominantes nas interações aves-flores na região Neotropical. Entretanto, pouco se conhece sobre as relações inter-específicas envolvendo aves dessas duas ordens em ambientes urbanos. Para avaliar o efeito do aumento induzido da disponibilidade de recurso para Apodiformes (beija-flores) e Passeriformes, foi realizado um estudo experimental utilizando bebedouros artificiais contendo soluções de sacarose à 10% e à 20% de concentração, que foram oferecidos ad libitum sense a espécies presentes em duas áreas ajardinadas na cidade de Uberlândia, MG. Seis bebedouros foram distribuídos em cada área, três contendo solução à 10% e outros três à 20%. Foram realizadas 20 horas de observação em cada área, totalizando 40 horas. As espécies de beija-flores identificadas nas áreas de estudo foram Eupetomena macroura, Chlorostilbon aureoventris e Amazilia fimbriata e as espécies Passeriformes foram Molothrus bonariensis, Myiozetetes similis, Todirostrum cinereum, Vireo olivaceus e Coereba flaveola. O pico de visitação das aves aos bebedouros ocorreu no início da manhã e início da tarde. Passeriformes e beija-flores diferiram significativamente na exploração, sendo que beija-flores preferiram bebedouros com soluções menos concentradas e Passeriformes, aqueles com soluções mais concentradas. Tendo em vista a sobreposição temporal na exploração do recurso e a segregação no uso de concentrações distintas, sugere-se que Apodiformes (Trochilidae) e Passeriformes possam estar realizando partição de nicho como estratégia para minimizar a competição. -

Lista Das Aves Do Brasil

90 Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee / Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos content / conteÚDO Abstract ............................. 91 Charadriiformes ......................121 Scleruridae .............187 Charadriidae .........121 Dendrocolaptidae ...188 Introduction ........................ 92 Haematopodidae ...121 Xenopidae .............. 195 Methods ................................ 92 Recurvirostridae ....122 Furnariidae ............. 195 Burhinidae ............122 Tyrannides .......................203 Results ................................... 94 Chionidae .............122 Pipridae ..................203 Scolopacidae .........122 Oxyruncidae ..........206 Discussion ............................. 94 Thinocoridae .........124 Onychorhynchidae 206 Checklist of birds of Brazil 96 Jacanidae ...............124 Tityridae ................207 Rheiformes .............................. 96 Rostratulidae .........124 Cotingidae .............209 Tinamiformes .......................... 96 Glareolidae ............124 Pipritidae ............... 211 Anseriformes ........................... 98 Stercorariidae ........125 Platyrinchidae......... 211 Anhimidae ............ 98 Laridae ..................125 Tachurisidae ...........212 Anatidae ................ 98 Sternidae ...............126 Rhynchocyclidae ....212 Galliformes ..............................100 Rynchopidae .........127 Tyrannidae ............. 218 Cracidae ................100 Columbiformes -

Acoustic Divergence with Gene Flow in a Lekking Hummingbird with Complex Songs

Acoustic Divergence with Gene Flow in a Lekking Hummingbird with Complex Songs Clementina Gonza´ lez, Juan Francisco Ornelas* Departamento de Biologı´a Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecologı´a AC, Xalapa, Veracruz, Me´xico Abstract Hummingbirds have developed a remarkable diversity of learned vocalizations, from single-note songs to phonologically and syntactically complex songs. In this study we evaluated if geographic song variation of wedge-tailed sabrewings (Campylopterus curvipennis) is correlated with genetic divergence, and examined processes that explain best the origin of intraspecific song variation. We contrasted estimates of genetic differentiation, genetic structure, and gene flow across leks from microsatellite loci of wedge-tailed sabrewings with measures for acoustic signals involved in mating derived from recordings of males singing at leks throughout eastern Mexico. We found a strong acoustic structure across leks and geography, where lek members had an exclusive assemblage of syllable types, differed in spectral and temporal measurements of song, and song sharing decreased with geographic distance. However, neutral genetic and song divergence were not correlated, and measures of genetic differentiation and migration estimates indicated gene flow across leks. The persistence of acoustic structuring in wedge-tailed sabrewings may thus best be explained by stochastic processes across leks, in which intraspecific vocal variation is maintained in the absence of genetic differentiation by postdispersal learning and social conditions, and by geographical isolation due to the accumulation of small differences, producing most dramatic changes between populations further apart. Citation: Gonza´lez C, Ornelas JF (2014) Acoustic Divergence with Gene Flow in a Lekking Hummingbird with Complex Songs. PLoS ONE 9(10): e109241.