Acoustic Divergence with Gene Flow in a Lekking Hummingbird with Complex Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Lista Das Aves Do Brasil

90 Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee / Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos content / conteÚDO Abstract ............................. 91 Charadriiformes ......................121 Scleruridae .............187 Charadriidae .........121 Dendrocolaptidae ...188 Introduction ........................ 92 Haematopodidae ...121 Xenopidae .............. 195 Methods ................................ 92 Recurvirostridae ....122 Furnariidae ............. 195 Burhinidae ............122 Tyrannides .......................203 Results ................................... 94 Chionidae .............122 Pipridae ..................203 Scolopacidae .........122 Oxyruncidae ..........206 Discussion ............................. 94 Thinocoridae .........124 Onychorhynchidae 206 Checklist of birds of Brazil 96 Jacanidae ...............124 Tityridae ................207 Rheiformes .............................. 96 Rostratulidae .........124 Cotingidae .............209 Tinamiformes .......................... 96 Glareolidae ............124 Pipritidae ............... 211 Anseriformes ........................... 98 Stercorariidae ........125 Platyrinchidae......... 211 Anhimidae ............ 98 Laridae ..................125 Tachurisidae ...........212 Anatidae ................ 98 Sternidae ...............126 Rhynchocyclidae ....212 Galliformes ..............................100 Rynchopidae .........127 Tyrannidae ............. 218 Cracidae ................100 Columbiformes -

Appendix S1. List of the 719 Bird Species Distributed Within Neotropical Seasonally Dry Forests (NSDF) Considered in This Study

Appendix S1. List of the 719 bird species distributed within Neotropical seasonally dry forests (NSDF) considered in this study. Information about the number of occurrences records and bioclimatic variables set used for model, as well as the values of ROC- Partial test and IUCN category are provide directly for each species in the table. bio 01 bio 02 bio 03 bio 04 bio 05 bio 06 bio 07 bio 08 bio 09 bio 10 bio 11 bio 12 bio 13 bio 14 bio 15 bio 16 bio 17 bio 18 bio 19 Order Family Genera Species name English nameEnglish records (5km) IUCN IUCN category Associated NDF to ROC-Partial values Number Number of presence ACCIPITRIFORMES ACCIPITRIDAE Accipiter (Vieillot, 1816) Accipiter bicolor (Vieillot, 1807) Bicolored Hawk LC 1778 1.40 + 0.02 Accipiter chionogaster (Kaup, 1852) White-breasted Hawk NoData 11 p * Accipiter cooperii (Bonaparte, 1828) Cooper's Hawk LC x 192 1.39 ± 0.06 Accipiter gundlachi Lawrence, 1860 Gundlach's Hawk EN 138 1.14 ± 0.13 Accipiter striatus Vieillot, 1807 Sharp-shinned Hawk LC 1588 1.85 ± 0.05 Accipiter ventralis Sclater, PL, 1866 Plain-breasted Hawk LC 23 1.69 ± 0.00 Busarellus (Lesson, 1843) Busarellus nigricollis (Latham, 1790) Black-collared Hawk LC 1822 1.51 ± 0.03 Buteo (Lacepede, 1799) Buteo brachyurus Vieillot, 1816 Short-tailed Hawk LC 4546 1.48 ± 0.01 Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Red-tailed Hawk LC 551 1.36 ± 0.05 Buteo nitidus (Latham, 1790) Grey-lined Hawk LC 1516 1.42 ± 0.03 Buteogallus (Lesson, 1830) Buteogallus anthracinus (Deppe, 1830) Common Black Hawk LC x 3224 1.52 ± 0.02 Buteogallus gundlachii (Cabanis, 1855) Cuban Black Hawk NT x 185 1.28 ± 0.10 Buteogallus meridionalis (Latham, 1790) Savanna Hawk LC x 2900 1.45 ± 0.02 Buteogallus urubitinga (Gmelin, 1788) Great Black Hawk LC 2927 1.38 ± 0.02 Chondrohierax (Lesson, 1843) Chondrohierax uncinatus (Temminck, 1822) Hook-billed Kite LC 1746 1.46 ± 0.03 Circus (Lacépède, 1799) Circus buffoni (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Long-winged Harrier LC 1270 1.61 ± 0.03 Elanus (Savigny, 1809) Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 29/09/2021. -

Syllable Sharing and Inter-Individual Syllable Variation in Anna's

Folia Zool. – 56(3): 307–318 (2007) Syllable sharing and inter-individual syllable variation in Anna’s hummingbird Calypte anna songs, in San Francisco, California Xiao-Jing YANG1, 2, 3, Fu-Min LEI1*, Gang WANG4 and Andrea J. JESSE5 1 Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; *e-mail: [email protected] 2 Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; e-mail: [email protected] 3 School of Environmental Studies, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China 4 Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-1800, U.S.A. 5 Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, CA 94118, U.S.A. Received 23 November 2006; Accepted 3 August 2007 A b s t r a c t. We examined the song sharing and variation pattern of 44 Anna’s hummingbird males at syllable level in San Francisco, California. Full songs of Anna’s hummingbird were composed of repeated blocks of phrases. Each male sang from three to six syllable types and syllable repertoire size averaged 5.1. A total of 38 syllable types were identified in songs of the population examined, which can be classified into five basic syllable categories. Each syllable category exhibited different variability among individuals. We quantified the variation of each category and found the variability was highest in the first phrase of song. Using Jaccard’s similarity coefficient, we found the syllable sharing among birds was significantly greater within one sample site than between sites. Using Mantel tests, we demonstrated that syllable sharing among birds tended to decline with the increase of inter-individual geographic distance. -

Morphological Facilitators for Vocal Learning Explored Through the Syrinx Anatomy of A

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.11.902734; this version posted January 13, 2020. The copyright holder for this1 preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Morphological facilitators for vocal learning explored through the syrinx anatomy of a 2 basal hummingbird 3 Amanda Monte1, Alexander F. Cerwenka2, Bernhard Ruthensteiner2, Manfred Gahr1, and 4 Daniel N. Düring1,3,4* 5 * Correspondence: [email protected] 6 1 – Department of Behavioural Neurobiology, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, 7 Seewiesen, Germany 8 2 – SNSB-Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Munich, Germany 9 3 – Institute of Neuroinformatics, ETH Zurich & University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 10 4 – Neuroscience Center Zurich (ZNZ), Zurich, Switzerland 11 Abstract 12 Vocal learning is a rare evolutionary trait that evolved independently in three avian clades: 13 songbirds, parrots, and hummingbirds. Although the anatomy and mechanisms of sound 14 production in songbirds are well understood, little is known about the hummingbird’s vocal 15 anatomy. We use high-resolution micro-computed tomography (μCT) and microdissection to 16 reveal the three-dimensional structure of the syrinx, the vocal organ of the black jacobin 17 (Florisuga fusca), a phylogenetically basal hummingbird species. We identify three unique 18 features of the black jacobin’s syrinx: (i) a shift in the position of the syrinx to the outside of 19 the thoracic cavity and the related loss of the sterno-tracheal muscle, (ii) complex intrinsic 20 musculature, oriented dorso-ventrally, and (iii) ossicles embedded in the medial vibratory 21 membranes. -

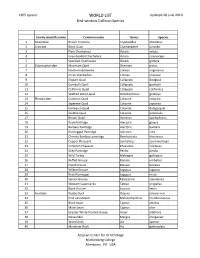

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet -

Birds in Atlantic Forest Fragments in North-East Brazil

Cotinga 20 Birds in Atlantic Forest fragments in north-east Brazil Luís Fábio Silveira, Fábio Olmos and Adrian J. Long Cotinga 20 (2003): 32–46 Durante o mês de outubro de 2001 os autores percorreram 15 fragmentos florestais no Estado de Alagoas, Brasil. O objetivo principal foi localizar novas populações e obter mais dados sobre os táxons endêmicos do ‘Centro Pernambuco’. Foram realizados censos em cada um dos fragmentos, que também foram analisados quanto ao estado geral de conservação. Discute-se a presença de espécies-chave, como grandes frugívoros ou aquelas sensíveis à fragmentação ou às mudanças na estrutura da vegetação. Os dois fragmentos mais importantes, com relação ao número de espécies encontrado e o número de táxons endêmicos, estão localizados na Usina Serra Grande (Mata do Pinto e Mata do Engenho Coimbra), onde foram registrados 16 táxons endêmicos e/ou ameaçados de extinção. Recomenda-se pesquisa taxonômica urgente, que procure evidenciar os táxons endêmicos do ‘Centro Pernambuco’, além de uma efetiva proteção aos fragmentos e às aves que ainda os habitam, uma maior vigilância contra a caça, a retirada de madeira e o desmatamento e um programa de reflorestamento que procure conectar os fragmentos mais próximos entre si. Sponsored by NBC In contrast to the Amazon forest, the Brazilian pernambucensis, T. aethiops distans and Iodopleura Atlantic Forest stretches along a broad latitudinal pipra leucopygia55,61. band, with little longitudinal variation. This The ‘Serra do Mar’ centre of avian endemism22 latitudinal gradient, from c.6oS to 32S, is further covers the Atlantic Forest from Rio Grande do Norte diversified by the montane ranges born of intense (c.7S) to Rio Grande do Sul (c.32S), with two main Cenozoic tectonic activity51 that occur throughout divisions: the narrow belt of coastal and montane much of the region. -

An Overlooked Hotspot for Birds in the Atlantic Forest

ARTICLE An overlooked hotspot for birds in the Atlantic Forest Vagner Cavarzere¹; Ciro Albano²; Vinicius Rodrigues Tonetti³; José Fernando Pacheco⁴; Bret M. Whitney⁵ & Luís Fábio Silveira⁶ ¹ Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná (UTFPR). Santa Helena, PR, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0510-4557. E-mail: [email protected] ² Brazil Birding Experts. Fortaleza, CE, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] ³ Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Ecologia. Rio Claro, SP, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2263-5608. E-mail: [email protected] ⁴ Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO). Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2399-7662. E-mail: [email protected] ⁵ Louisiana State University, Museum of Natural Science. Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Estados Unidos. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8442-9370. E-mail: [email protected] ⁶ Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Museu de Zoologia (MZUSP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2576-7657. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Montane and submontane forest patches in the state of Bahia, Brazil, are among the few large and preserved Atlantic Forests remnants. They are strongholds of an almost complete elevational gradient, which harbor both lowland and highland bird taxa. Despite being considered a biodiversity hotspot, few ornithologists have surveyed these forests, especially along elevational gradients. Here we compile bird records acquired from systematic surveys and random observations carried out since the 1980s in a 7,500 ha private protected area: Serra Bonita private reserve. We recorded 368 species, of which 143 are Atlantic Forest endemic taxa. -

Bioone COMPLETE

BioOne COMPLETE Introduction to the Skeleton of Hummingbirds (Aves: Apodiformes, Trochilidae) in Functional and Phylogenetic Contexts Author: Zusi, Richard L., Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 37012, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013, USA Source: Ornithological Monographs No. 77 Published By: American Ornithological Society URL: https://doi.org/10.1525/om.2013.77.L1 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne's Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/ebooks on 1/14/2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by University of New Mexico Ornithological Monographs Volume (2013), No. 77, 1-94 © The American Ornithologists' Union, 2013. Printed in USA. INTRODUCTION TO THE SKELETON OF HUMMINGBIRDS (AVES: APODIFORMES, TROCHILIDAE) IN FUNCTIONAL AND PHYLOGENETIC CONTEXTS R ic h a r d L. Z u s i1 Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Vocal Learning in the Costa's Hummingbird a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Vocal Learning in the Costa’s Hummingbird A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology by Katherine Elizabeth Johnson September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher Clark, Chairperson Dr. Mark Chappell Dr. Jessica Purcell Copyright by Katherine Elizabeth Johnson 2019 The Dissertation of Katherine Elizabeth Johnson is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements It is amazing how many people it took to complete this dissertation and I am so grateful to them all for their kind assistance. My study had unique animal care demands and many people helped to keep the hummingbirds alive and thriving. So special thanks to David Rankin, Sean Wilcox, Krista LePiane, Brian Myers, Emily Mistick, Ayala Berger, Lilly Collins, Jenny Hazelhurst for their efforts! Thanks to my lab mates, Sean Wilcox, Krista LePiane, Ayala Berger, for their friendship and support. Also, a very sincere appreciation to David Ranking who is one of the world’s greatest hummingbird nest finders! So much of my success depended on your efforts and I can never thank you enough! Dr. Erin Rankin was also most generous with her time and assistance. I also want to express my appreciation to the Anza Borrego Paul Jorgenson Bird Grant, the Animal Behavior Society, San Diego Global Zoo, and the Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden for their invaluable assistance. I wish to especially thank my Committee Members Dr. Mark Chappell, Dr. Jessica Purcell, Dr. Khaleel Razak, Dr. Wendy Saltzman, and Dr. Rachel Wu who by refusing to accept my first proposal, made the project so much better! And finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to my advisor and mentor Chris Clark. -

Dokumentation Neuer Vogel-Taxa, 13 – Bericht Für 2017 151-171 Vogelwarte 57, 2019: 151 – 171 © DO-G, Ifv, MPG 2019

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Vogelwarte - Zeitschrift für Vogelkunde Jahr/Year: 2019 Band/Volume: 57_2019 Autor(en)/Author(s): Martens Jochen, Bahr Norbert Artikel/Article: Dokumentation neuer Vogel-Taxa, 13 – Bericht für 2017 151-171 Vogelwarte 57, 2019: 151 – 171 © DO-G, IfV, MPG 2019 Dokumentation neuer Vogel-Taxa, 13 – Bericht für 2017 Jochen Martens & Norbert Bahr Martens J & Bahr N 2019: Documentation of new bird taxa, part 13. Report for 2017. Vogelwarte 57, 2019: 151-171. This report is the thirteenth of a series and presents the results of a comprehensive literature screening in search for new bird taxa described in 2017, namely new genera, species and subspecies worldwide. We tracked names of four new genera, eight species and eight subspecies new to science, which were correctly described according to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. The new genera are within Trochilidae, Leiotrichidae, Muscicapidae, and Thraupidae. One each of the new species refer to Trochilidae, Strigidae, Psittacidae, Pipridae, Rhinocryptidae, Meliphagidae, Muscicapidae, and Thraupidae; three belong to Passeriformes, the remainder to Non-Passeriformes. New subspecies were named within Apodidae (2), Ac- cipitridae (1), Psittacidae (3), Paradisaeidae (1) and Aegithalidae (1). One new genus (Remsenornis, Thraupidae) fell in syn- onymy immediately after publication and another new genus name (Elliotia, Trochilidae) is preoccupied by an older genus name for a beetle und thus not available. The description of one new parrot species (Amazona, Psittacidae) most probably is based on aviary-bred hybrids. In several cases, the populations in question now considered to represent a new species were known since long (in genera Megascops, Myzomela, Sholicola).