UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Vocal Learning in the Costa's Hummingbird a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden Using Native Plants

United States Department of Agriculture Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden Using Native Plants Black-chinned Hummingbird feeding on mountain larkspur, fireweed, and wild bergamot (clockwise from top) Forest National Publication April Service Headquarters Number FS-1046 2015 Hummingbird garden guide Many of us enjoy the beauty of flowers in our backyard and community gardens. Growing native plants adds important habitat for hummingbirds and other wildlife—especially pollinators. Even small backyard gardens can make a difference. Gardening connects us to nature and helps us better understand how nature works. This guide will help you create a hummingbird- What do hummingbirds, friendly garden. butterflies, and bees have in common? They all pollinate flowering plants. Broad-tailed Hummingbird feeding on scarlet gilia Hummingbirds are Why use native plants in restricted to the Americas with more your garden? than 325 species of Hummingbirds have evolved with hummingbirds in North, Central, and native plants, which are best adapted South America. to local growing seasons, climate, and soil. They prefer large, tubular flowers that are often (but not always) red in color. In this guide, we feature seven hummingbirds that breed in the United States. For each one, we also highlight two native plants found in its breeding range. These native plants are easy to grow, need little water once established, and offer hummingbirds abundant nectar. 2 Hummingbirds and pollination Ruby-throated Hummingbird feeding on the At rest, a hummer’s nectar and pollen heart beats an of blueberry flowers average of 480 beats per minute. On cold nights, it goes into What is pollination? torpor (hibernation- like state), and its Pollination is the process of moving pollen heart rate drops to (male gamete) from one flower to the ovary of another 45 to 180 beats per minute. -

Paper Describing Hummingbird-Sized Dinosaur Retracted 24 July 2020, by Bob Yirka

Paper describing hummingbird-sized dinosaur retracted 24 July 2020, by Bob Yirka teeth. Some in the field were so sure that it was a lizard and not a dinosaur that they wrote and uploaded a paper to the bioRxiv preprint server outlining their concerns. The authors of the paper then published a response addressing their concerns and refuting the skeptics' arguments. That was followed by another team reporting that they had found a similar fossil and after studying it, had deemed it to be a lizard. In reviewing both the paper and the evidence presented by others in the field, the editors at Nature chose to retract the paper. A CT scan of the skull of Oculudentavis by LI Gang, The researchers who published the original paper Oculudentavis means eye-tooth-bird, so named for its appear to be divided on their assessment of the distinctive features. Credit: Lars Schmitz retraction, with some insisting there was no reason for the paper to be retracted and others acknowledging that they had made a mistake when they classified their find as a dinosaur. In either The journal Nature has issued a retraction for a case, all of the researchers agree that the work paper it published March 11th called they did on the fossil was valid and thus the paper "Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous could be used as a source by others in the future—it period of Myanmar." The editorial staff was alerted is only the classification of the find that has been to a possible misclassification of the fossil put in doubt. -

Spider Webs and Windows As Potentially Important Sources of Hummingbird Mortality

J. Field Ornithol., 68(1):98--101 SPIDER WEBS AND WINDOWS AS POTENTIAIJJY IMPORTANT SOURCES OF HUMMINGBIRD MORTALITY DEVON L. G•nqAM Departmentof Biology Universityof Miami PO. Box 249118 Coral Gables,Florida, 33124 USA Abstract.--Sourcesof mortality for adult hummingbirdsare varied, but most reports are of starvationand predation by vertebrates.This paper reportstwo potentiallyimportant sources of mortality for tropical hermit hummingbirds,entanglement in spiderwebs and impacts with windows.Three instancesof hermit hummingbirds(Phaethornis spp.) tangled in webs of the spider Nephila clavipesin Costa Rica are reported. The placement of webs of these spidersin sitesfavored by hermit hummingbirdssuggests that entanglementmay occur reg- ularly. Observationsat buildingsalso suggest that traplining hermit hummingbirdsmay be more likely to die from strikingwindows than other hummingbirds.Window kills may need to be consideredfor studiesof populationsof hummingbirdslocated near buildings. TELAS DE ARAI•A Y VENTANAS COMO FUENTES POTENCIALES DE MORTALIDAD PARA ZUMBADORES Sinopsis.--Lasfuentes de mortalidad para zumbadoresson variadas.Pero la mayoria de los informes se circunscribena inanicitn y a depredacitn pot parte de vertebrados.En este trabajo se informan dos importantesfuentes de mortalidad para zumbadorestropicales (Phaethornisspp.) como los impactoscontra ventanasy el enredarsecon tela de arafia. Se informan tres casosde zumbadoresenredados con tela de la arafia Nephila clavipesen Costa Rica. La construccitn de las telas de arafia en lugares -

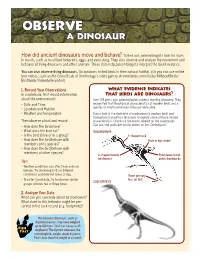

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

Hummingbird Haven Backyard Habitat for Wildlife

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hummingbird Haven Backyard Habitat for Wildlife From late March through mid November, if you and then spending their winters in Mexico. look carefully, you may find a small flying Beating their wings 2.7 million times, the jewel in your backyard. The ruby-throated ruby-throated hummingbird flies 500 miles hummingbird may be seen zipping by your nonstop across the Gulf of Mexico during porch or flitting about your flower migration. This trip averages 18-20 hours garden. Inquisitive by nature, these but with a strong tail wind, the flight takes tiny birds will fly close to investigate ten hours. To survive, migrating hummers your colorful blouse or red baseball cap. must store fat and fuel up before and right The hummingbird, like many species of after crossing the Gulf—there are no wildlife is plagued by loss of habitat. sources of nectar over the ocean! However, by providing suitable backyard habitat you can help this flying jewel of a bird. Hummingbird Flowers Flowers Height Color Bloom time Hummingbird Habitat A successful backyard haven for hummingbirds contains a Herbaceous Plants variety of flowering plants including tall and medium trees, Bee Balm 2-4' W, P, R, L summer shrubs, vines, perennial and annual flowers. Flowering plants Blazing Star 2-6' L summer & fall provide hummers with nectar for energy and insects for Cardinal Flower 2-5' R summer protein. Trees and shrubs provide vertical structure for nesting, perching and shelter. No matter what size garden, try Columbine 1-4' all spring & summer to select a variety of plants to ensure flowering from spring Coral Bells 6-12" W, P, R spring through fall. -

Hummingbirds for Kids

Hummingbird Facts & Activity for Kids Hummingbird Facts: Georgia is home to 11 hummingbird species during the year: 1. ruby-throated 2. black-chinned 3. rufous 4. calliope 5. magnificent 6. Allen's 7. Anna's 8. broad-billed 9. green violet-ear 10. green-breasted mango 11. broad-tailed The ruby-throated hummingbird is the only species of hummingbird known to nest to Georgia. These birds weigh around 3 grams-- as little as a first-class letter. The female builds the walnut-sized nest without any help from her mate, a process that can take up to 12 days. The female then lays two eggs, each about the size of a black-eyed pea. In Georgia, female ruby-throated hummers produce up to two broods per year. Nests are typically built on a small branch that is parallel to or dips downward. The birds sometimes rebuild the nest they used the previous year. Keep at least one feeder up throughout the year. You cannot keep hummingbirds from migration by leaving feeders up during the fall and winter seasons. Hummingbirds migrate in response to a decline in day length, not food availability. Most of the rare hummingbirds found in Georgia are seen during the winter. Homemade Hummingbird Feeders: You can use materials from around your home to make a feeder. Here is a list of what you may use: • Small jelly jar • Salt shaker • Wire or coat hanger for hanging • Red pipe cleaners Homemade Hummingbird Food: • You will need--- 1 part sugar to 4 parts water • Boil the water for 2–3 minutes before adding sugar. -

The Evolution of Human Vocal Emotion

EMR0010.1177/1754073920930791Emotion ReviewBryant 930791research-article2020 SPECIAL SECTION: EMOTION IN THE VOICE Emotion Review Vol. 13, No. 1 (January 2021) 25 –33 © The Author(s) 2020 ISSN 1754-0739 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073920930791 10.1177/1754073920930791 The Evolution of Human Vocal Emotion https://journals.sagepub.com/home/emr Gregory A. Bryant Department of Communication, Center for Behavior, Evolution, and Culture, University of California, Los Angeles, USA Abstract Vocal affect is a subcomponent of emotion programs that coordinate a variety of physiological and psychological systems. Emotional vocalizations comprise a suite of vocal behaviors shaped by evolution to solve adaptive social communication problems. The acoustic forms of vocal emotions are often explicable with reference to the communicative functions they serve. An adaptationist approach to vocal emotions requires that we distinguish between evolved signals and byproduct cues, and understand vocal affect as a collection of multiple strategic communicative systems subject to the evolutionary dynamics described by signaling theory. We should expect variability across disparate societies in vocal emotion according to culturally evolved pragmatic rules, and universals in vocal production and perception to the extent that form–function relationships are present. Keywords emotion, evolution, signaling, vocal affect Emotional communication is central to social life for many ani- 2001; Pisanski, Cartei, McGettigan, Raine, & Reby, 2016; mals. Beginning with Darwin -

Science News | December 19, 2009 Feature | Humans Wonder, Anybody Home?

FEATURE | HUMANS WONDER, ANYBODY HOME? To prevent Shania the octopus from becom- Humans wonder, ing bored, keepers at the National Aquarium in Washington, D.C., gave her a Mr. Potato Head filled with fish to snuggle. Researchers anybody are now looking beyond behavior into the brain for signs of awareness in birds and invertebrates. home? Brain structure and circuitry offer clues to consciousness in nonmammals By Susan Gaidos ne afternoon while participat except for the fact that Betty was a New ing in studies in a University Caledonian crow. of Oxford lab, Abel snatched Betty isn’t the only crow with such a hook away from Betty, leav conceptual ingenuity. Nor are crows the Oing her without a tool to complete a task. only members of the animal kingdom to Spying a piece of straight wire nearby, exhibit similar mental powers. Animals POST WASHINGTON THE she picked it up, bent one end into a can do all sorts of clever things: Studies EARY/ L ’ hook and used it to finish the job. Noth of chimpanzees, gorillas, dolphins and O ILL ing about this story was remarkable, birds have found that some can add, B 22 | SCIENCE NEWS | December 19, 2009 www.sciencenews.org FEATURE | HUMANS WONDER, ANYBODY HOME? subtract, create sentences, plan ahead objects in their visual field. “This raises or deceive others. the intriguing question whether con Brain-on-brain comparisons To carry out such tasks, these animals scious experience requires the specific In an effort to find signs of conscious- ness, scientists are identifying analo- must be drawing on past experiences and structure of human or primate brains,” gous structures (same coloring) among then using them along with immediate biologist Donald Griffin wrote inAnimal the brains of humans, birds, octopuses perceptions to make sense of it all. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Going Beyond Just-So Stories Response to Commentary on Key on Fish Pain

Animal Sentience 2016.022: Response to Commentary on Key on Fish Pain Going beyond just-so stories Response to Commentary on Key on Fish Pain Brian Key School of Biomedical Sciences University of Queensland Abstract: Colloquial arguments for fish feeling pain are deeply rooted in anthropometric tendencies that confuse escape responses to noxious stimuli with evidence for consciousness. More developed arguments often rely on just-so stories of fish displaying complex behaviours as proof of consciousness. In response to commentaries on the idea that fish do not feel pain, I raise the need to go beyond just-so stories and to rigorously analyse the neural circuitry responsible for specific behaviours using new and emerging technologies in neuroscience. By deciphering the causal relationship between neural information processing and conscious behaviour, it should be possible to assess cogently the likelihood of whether a vertebrate species has the neural hardware necessary to — at least — support the feeling of pain. Brian Key [email protected] is Head of the Brain Growth and Regeneration Lab at the University of Queensland. He is dedicated to understanding the principles of stem cell biology, differentiation, axon guidance, plasticity, regeneration and development of the brain. http://www.uq.edu.au/sbms/staff/brian-key Just-so stories In this response to commentaries on the target article “Fish do not feel pain” (Key), I do not plan to interrogate either the putative behavioural evidence or the just-so stories previously proposed as supportive of fish feeling pain (Balcombe; Braithwaite & Droege; Broom; Brown; Dinets; Ng). These claims have been adequately addressed and refuted in recent literature (Key, 2015a and 2015b; Rose et al., 2014). -

A Novel Reinforcement Model of Birdsong Vocalization Learning

A Novel Reinforcement Model of Birdsong Vocalization Learning Kenji Doya Terrence J. Sejnowski ATR Human Infonnation Processing Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Laboratories UCSD and Salk Institute, 2-2 Hikaridai, Seika, Kyoto 619-02, Japan San Diego, CA 92186-5800, USA Abstract Songbirds learn to imitate a tutor song through auditory and motor learn ing. We have developed a theoretical framework for song learning that accounts for response properties of neurons that have been observed in many of the nuclei that are involved in song learning. Specifically, we suggest that the anteriorforebrain pathway, which is not needed for song production in the adult but is essential for song acquisition, provides synaptic perturbations and adaptive evaluations for syllable vocalization learning. A computer model based on reinforcement learning was con structed that could replicate a real zebra finch song with 90% accuracy based on a spectrographic measure. The second generation of the bird song model replicated the tutor song with 96% accuracy. 1 INTRODUCTION Studies of motor pattern generation have generally focussed on innate motor behaviors that are genetically preprogrammed and fine-tuned by adaptive mechanisms (Harris-Warrick et al., 1992). Birdsong learning provides a favorable opportunity for investigating the neuronal mechanisms for the acquisition of complex motor patterns. Much is known about the neuroethology of bird song and its neuroanatomical substrate (see Nottebohm, 1991 and Doupe, 1993 for reviews), but relatively little is known about the overall system from a computational viewpoint. We propose a set of hypotheses for the functions of the brain nuclei in the song system and explore their computational strength in a model based on biological constraints. -

Acoustic Divergence with Gene Flow in a Lekking Hummingbird with Complex Songs

Acoustic Divergence with Gene Flow in a Lekking Hummingbird with Complex Songs Clementina Gonza´ lez, Juan Francisco Ornelas* Departamento de Biologı´a Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecologı´a AC, Xalapa, Veracruz, Me´xico Abstract Hummingbirds have developed a remarkable diversity of learned vocalizations, from single-note songs to phonologically and syntactically complex songs. In this study we evaluated if geographic song variation of wedge-tailed sabrewings (Campylopterus curvipennis) is correlated with genetic divergence, and examined processes that explain best the origin of intraspecific song variation. We contrasted estimates of genetic differentiation, genetic structure, and gene flow across leks from microsatellite loci of wedge-tailed sabrewings with measures for acoustic signals involved in mating derived from recordings of males singing at leks throughout eastern Mexico. We found a strong acoustic structure across leks and geography, where lek members had an exclusive assemblage of syllable types, differed in spectral and temporal measurements of song, and song sharing decreased with geographic distance. However, neutral genetic and song divergence were not correlated, and measures of genetic differentiation and migration estimates indicated gene flow across leks. The persistence of acoustic structuring in wedge-tailed sabrewings may thus best be explained by stochastic processes across leks, in which intraspecific vocal variation is maintained in the absence of genetic differentiation by postdispersal learning and social conditions, and by geographical isolation due to the accumulation of small differences, producing most dramatic changes between populations further apart. Citation: Gonza´lez C, Ornelas JF (2014) Acoustic Divergence with Gene Flow in a Lekking Hummingbird with Complex Songs. PLoS ONE 9(10): e109241.