Download Preprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comprehensive Multilocus Phylogeny of the Neotropical Cotingas

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 81 (2014) 120–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A comprehensive multilocus phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae, Aves) with a comparative evolutionary analysis of breeding system and plumage dimorphism and a revised phylogenetic classification ⇑ Jacob S. Berv 1, Richard O. Prum Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208105, New Haven, CT 06520, USA article info abstract Article history: The Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae: Aves) are a group of passerine birds that are characterized by Received 18 April 2014 extreme diversity in morphology, ecology, breeding system, and behavior. Here, we present a compre- Revised 24 July 2014 hensive phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas based on six nuclear and mitochondrial loci (7500 bp) Accepted 6 September 2014 for a sample of 61 cotinga species in all 25 genera, and 22 species of suboscine outgroups. Our taxon sam- Available online 16 September 2014 ple more than doubles the number of cotinga species studied in previous analyses, and allows us to test the monophyly of the cotingas as well as their intrageneric relationships with high resolution. We ana- Keywords: lyze our genetic data using a Bayesian species tree method, and concatenated Bayesian and maximum Phylogenetics likelihood methods, and present a highly supported phylogenetic hypothesis. We confirm the monophyly Bayesian inference Species-tree of the cotingas, and present the first phylogenetic evidence for the relationships of Phibalura flavirostris as Sexual selection the sister group to Ampelion and Doliornis, and the paraphyly of Lipaugus with respect to Tijuca. -

1 AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change Th

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-A 4 September 2019 No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero 02 05 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 1) 03 11 Change the generic classification of the Trochilini (part 2) 04 18 Split Garnet-throated Hummingbird Lamprolaima rhami 05 22 Recognize Amazilia alfaroana as a species not of hybrid origin, thus moving it from Appendix 2 to the main list 06 26 Change the linear sequence of species in the genus Dendrortyx 07 28 Make two changes concerning Starnoenas cyanocephala: (a) assign it to the new monotypic subfamily Starnoenadinae, and (b) change the English name to Blue- headed Partridge-Dove 08 32 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 09 36 Split Royal Tern Thalasseus maximus into two species 10 39 Recognize Great White Heron Ardea occidentalis as a species 11 41 Change the English name of Checker-throated Antwren Epinecrophylla fulviventris to Checker-throated Stipplethroat 12 42 Modify the linear sequence of species in the Phalacrocoracidae 13 49 Modify various linear sequences to reflect new phylogenetic data 1 2020-A-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 532 Change the English name of Olive Warbler Peucedramus taeniatus to Ocotero Background: “Warbler” is perhaps the most widely used catch-all designation for passerines. Its use as a meaningful taxonomic indicator has been defunct for well over a century, as the “warblers” encompass hundreds of thin-billed, insectivorous passerines across more than a dozen families worldwide. This is not itself an issue, as many other passerine names (flycatcher, tanager, sparrow, etc.) share this common name “polyphyly”, and conventions or modifiers are widely used to designate and separate families that include multiple groups. -

Continued Bird Surveys in Southeastern Coastal Brazilian Atlantic Forests and the Importance of Conserving Elevational Gradients

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 22(4), 383-409 ARTICLE December 2014 Continued bird surveys in southeastern coastal Brazilian Atlantic forests and the importance of conserving elevational gradients Vagner Cavarzere1,2,4, Thiago Vernaschi Vieira da Costa1,2, Giulyana Althmann Benedicto3, Luciano Moreira-Lima1,2 and Luís Fábio Silveira2 1 Pós-Graduação, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo. Rua do Matão, travessa 14, 101, CEP 05508- 900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 2 Seção de Aves, Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo. Avenida Nazaré, 481, CEP 04218-970, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 3 Rua Tiro Onze, 04, CEP 11013-040, Santos, SP, Brazil. 4 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 15 January 2014. Accepted on 18 November 2014. ABSTRACT: Although the Atlantic forest is the best-studied Brazilian phytogeographic domain, few coastal municipalities of the state of São Paulo can count on published and critically revised bird species list, which are important initial steps to organize conservation inniciatives. Here we present historical records from Bertioga, a northern coastline municipality of the state of São Paulo, as well as recent records obtained in surveys during the past years within the municipality. Surveying methods, carried out between 2008-2011, included point counts, 10-species lists, transect counts and mist nets. This compendium resulted in 330 documented species, 90 of which still await documentation. Of these 420 bird species, 85 (20.4%) are Atlantic forest endemic species and as many as eight, six and 23 are threatened at the global, national and state levels, respectively. Seventeen species are reported from Bertioga for the first time. -

Observations on a Nest of Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes Scutatus

Observations on a nest of Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes scutatus Marcelo Ferreira de Vasconcelos, Prinscila Neves Vasconcelos and Geraldo Wilson Fernandes Cotinga 16 (2001): 53–57 Foram feitas observações em um ninho do beija-flor-de-gravata-verde Augastes scutatus em uma localidade de campo rupestre na Serra do Cipó, Minas Gerais. Apenas uma fêmea desta espécie foi observada cuidando dos ninhegos. Durante as observações foram registrados ataques de um indivíduo de beija-flor-tesoura Eupetomena macroura ao ninho de A. scutatus. Pela primeira vez são descritos os comportamentos de cuidado parental e a evolução da plumagem do ninhego de A. scutatus. Introduction Life histories of the endemic bird species of the Espinhaço range in south-east Brazil (Endemic Bird Area 07315) are poorly known, with some exceptions2,4,6,7,8,9,16–19. Hyacinth Visorbearer Augastes scutatus, a near-threatened species1, is restricted to campos rupestres of the Espinhaço10,11,13–15. Apart from a description of the nest4,5,9,11, virtually nothing is known of its breeding biology. This paper describes observations at a nest of this little-known hummingbird. Material and methods Observations were undertaken on 23, 26 and 29 June and 3, 6, 9, 11 and 16 July 1999, totalling 37 hours. The nest was watched with 8 x 40 binoculars from a distance of 12 m. Activity was described in a notebook. Furthermore, we filmed and photographed all behaviours which occurred at a distance of 4 m or less from the nest. We did not measure the nestlings to avoid stress to the birds. -

Aves:Trochilidae) E Passeriformes

EFEITO DA INTRODUÇÃO DE BEBEDOUROS ARTIFICIAIS NA PARTIÇÃO DE NICHO ENTRE APODIFORMES (AVES:TROCHILIDAE) E PASSERIFORMES. JOVÂNIA GONÇALVES TEIXEIRA¹, MARIANA ABRAHÃO ASSUNÇÃO¹, CELINE DE MELO ². RESUMO: Aves das ordens Apodiformes e Passeriformes representam grupos de alta importância ecológica, sendo dominantes nas interações aves-flores na região Neotropical. Entretanto, pouco se conhece sobre as relações inter-específicas envolvendo aves dessas duas ordens em ambientes urbanos. Para avaliar o efeito do aumento induzido da disponibilidade de recurso para Apodiformes (beija-flores) e Passeriformes, foi realizado um estudo experimental utilizando bebedouros artificiais contendo soluções de sacarose à 10% e à 20% de concentração, que foram oferecidos ad libitum sense a espécies presentes em duas áreas ajardinadas na cidade de Uberlândia, MG. Seis bebedouros foram distribuídos em cada área, três contendo solução à 10% e outros três à 20%. Foram realizadas 20 horas de observação em cada área, totalizando 40 horas. As espécies de beija-flores identificadas nas áreas de estudo foram Eupetomena macroura, Chlorostilbon aureoventris e Amazilia fimbriata e as espécies Passeriformes foram Molothrus bonariensis, Myiozetetes similis, Todirostrum cinereum, Vireo olivaceus e Coereba flaveola. O pico de visitação das aves aos bebedouros ocorreu no início da manhã e início da tarde. Passeriformes e beija-flores diferiram significativamente na exploração, sendo que beija-flores preferiram bebedouros com soluções menos concentradas e Passeriformes, aqueles com soluções mais concentradas. Tendo em vista a sobreposição temporal na exploração do recurso e a segregação no uso de concentrações distintas, sugere-se que Apodiformes (Trochilidae) e Passeriformes possam estar realizando partição de nicho como estratégia para minimizar a competição. -

Antipredator Deception in Terrestrial Vertebrates

Current Zoology 60 (1): 16–25, 2014 Antipredator deception in terrestrial vertebrates Tim CARO* Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, and Center of Population Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Abstract Deceptive antipredator defense mechanisms fall into three categories: depriving predators of knowledge of prey’s presence, providing cues that deceive predators about prey handling, and dishonest signaling. Deceptive defenses in terrestrial vertebrates include aspects of crypsis such as background matching and countershading, visual and acoustic Batesian mimicry, active defenses that make animals seem more difficult to handle such as increase in apparent size and threats, feigning injury and death, distractive behaviours, and aspects of flight. After reviewing these defenses, I attempt a preliminary evaluation of which aspects of antipredator deception are most widespread in amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds [Current Zoology 60 (1): 16 25, 2014]. Keywords Amphibians, Birds, Defenses, Dishonesty, Mammals, Prey, Reptiles 1 Introduction homeotherms may increase the distance between prey and the pursuing predator or dupe the predator about the In this paper I review forms of deceptive antipredator flight path trajectory, or both (FitzGibbon, 1990). defenses in terrestrial vertebrates, a topic that has been Last, an antipredator defense may be a dishonest largely ignored for 25 years (Pough, 1988). I limit my signal. Bradbury and Vehrencamp (2011) state that “true scope to terrestrial organisms because lighting condi- deception occurs when a sender produces a signal tions in water are different from those in the air and whose reception will benefit it at the expense of the antipredator strategies often differ in the two environ- receiver regardless of the condition with which the sig- ments. -

Avian Distraction Displays: a Review

1 Running head: Distraction displays review 2 Avian distraction displays: a review 3 4 ROSALIND K. HUMPHREYS1* & GRAEME D. RUXTON1 5 1School of Biology, University of St Andrews, Dyer's Brae House, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9TH, UK 6 *Corresponding author. 7 Email: [email protected] 8 ORCiD: Rosalind K. Humphreys: 0000-0001-7266-7523, Graeme D. Ruxton: 0000-0001-8943-6609 9 10 Distraction displays are conspicuous behaviours functioning to distract a predator’s attention away 11 from the displayer’s nest or young, thereby reducing the chance of offspring being discovered and 12 predated. Distraction is one of the riskier parental care tactics, as its success derives from the 13 displaying parent becoming the focus of a predator’s attention. Such displays are prominent in birds, 14 primarily shorebirds, but the last comprehensive review of distraction was in 1984. Our review aims 15 to provide an updated synthesis of what is known about distraction displays in birds, and to open up 16 new areas of study by highlighting some of the key avenues to explore and the broadened ecological 17 perspectives that could be adopted in future research. We begin by drawing attention to the 18 flexibility of form that distraction displays can take and providing an overview of the different avian 19 taxa known to use anti-predator distraction displays, also examining species-specific sex differences 20 in use. We then explore the adaptive value and evolution of distraction displays, before considering 21 the variation seen in the timing of their use over a reproductive cycle. An evaluation of the efficacy 22 of distraction compared with alternative anti-predator tactics is then conducted via a cost-benefit 23 analysis. -

Holiday at Ecuador's Wildsumaco Lodge

® field guides BIRDING TOURS WORLDWIDE [email protected] • 800•728•4953 ITINERARY HOLIDAY AT ECUADOR’S WILDSUMACO LODGE December 27, 2020-January 6, 2021 The Masked Trogon, decked out in holiday colors, is just one of the tropical beauties we’ll see on this short tour to one of South America’s best birding areas. Photograph by participant Whitney Mortimer. We include here information for those interested in the 2020 Field Guides Ecuador’s Wildsumaco Lodge tour: ¾ a general introduction to the tour ¾ a description of the birding areas to be visited on the tour ¾ an abbreviated daily itinerary with some indication of the nature of each day’s birding outings These additional materials will be made available to those who register for the tour: ¾ an annotated list of the birds recorded on a previous year’s Field Guides trip to the area, with comments by guide(s) on notable species or sightings (may be downloaded from our web site) ¾ a detailed information bulletin with important logistical information and answers to questions regarding accommodations, air arrangements, clothing, currency, customs and immigration, documents, health precautions, and personal items ¾ a reference list ¾ a Field Guides checklist for preparing for and keeping track of the birds we see on the tour ¾ after the conclusion of the tour, a list of birds seen on the tour The upper tropical zone along the eastern base of the Andes has long been recognized as one of the ornithologically richest ecosystems on earth. However, reaching this zone has been difficult at best for many years, usually involving camping and/or long drives from the nearest accommodations in order to bird mostly along a road. -

Brazil Atlantic Coastal Forest II 8Th October to 15Th October 2022 (8 Days)

Brazil Atlantic Coastal Forest II 8th October to 15th October 2022 (8 days) Red-necked Tanager by Dubi Shapiro Throughout this tour, you will be based at a comfortable and beautifully located eco-lodge, situated in the 57 000 hectare Tres Picos State Park only a relatively short distance from Rio de Janeiro. Here you will explore the numerous mosaics of trails around the lodge grounds and take short drives to explore several other habitats and elevations surrounding the reserve. Some of the avian gems that will be sought during this tour include Three-toed Jacamar, spectacular Swallow-tailed Cotinga, Saffron Toucanet, Green-crowned Plovercrest, Saw-billed Hermit, Black-billed Scythebill, Giant and RBL – Brazil: Atlantic Coastal Forest Itinerary 2 White-bearded Antshrike, Blond-crested Woodpecker, Shrike-like and Black-and-gold Cotingas, and the beautiful Brazilian Tanager. This will be a very comfortably paced tour with no long drives! On some days you will have packed lunches, while on others you will return to the lodge for lunch. There will be ample time to unwind and to enjoy birding from the lodge grounds or even while relaxing by the natural swimming pool. Fruit trays and hummingbird feeders placed throughout the grounds attract a variety of parakeets, hummingbirds and tanagers. Birds are confiding and photographic opportunities are excellent. This tour captures the best of Brazil’s Atlantic Rainforest endemic bird species, and after a week of birding, you can expect to have seen up to 250 bird species, including 70 endemics! THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Transfer from Rio de Janeiro to our accommodation Day 2 High altitude excursion to Pico de Caladonia Day 3 Lodge grounds and Blue Circular & Orchid Garden Trail Day 4 Wetlands excursion & lowland forest Day 5 Three-toed Jacamar excursion Day 6 Cedae & Theodoro Trail Day 7 Macae de Cima & lodge trails Day 8 Departure to Rio de Janeiro TOUR MAP… RBL – Brazil: Atlantic Coastal Forest Itinerary 3 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Rio de Janeiro to our accommodation. -

ZOOCIÊNCIAS 9(2): 193-198, Dezembro 2007

Hummingbird pollination in Schwartzia adamantium .193 ISSN 1517-6770 Revista Brasileira de ZOOCIÊNCIAS 9(2): 193-198, dezembro 2007 Hummingbird pollination in Schwartzia adamantium (Marcgraviaceae) in an area of Brazilian Savanna Rafael Arruda1,2, Jania Cabrelli Salles1 & Paulo Eugênio de Oliveira1 1Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, 38400-902, CP 593, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil 2Present address and corresponding author: Coordenação de Pesquisas em Ecologia, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, 69011-970, CP 478, Manaus, AM, Brazil. [email protected] Abstract. Some authors have suggested that, in bird-pollinated species of Marcgraviaceae, perching birds are more adequate pollinators than hovering birds, due to the inflorescence structure and floral biology. In this study, we report territorial behavior of the swallow-tailed hummingbird Eupetomena macroura in Schwartzia adamantium. We analyzed the time spent in foraging behavior and territorial defense by the hummingbird, and the nectar availability of S. adamantium. The hummingbird spent almost 96% of the time perching. We registered 97 invasions of the territory always by others hummingbirds. During the observation period, no perching birds visited S. adamantium. Nectar volume varied from 15.0 to 114.0 µL, and sugar concentration varied from 5.5 to 27.1%. Despite that hummingbirds possibly play a minor role in the reproduction of ornithophilous Marcgraviaceae species, and occasionally touched the anthers and/or stigma, our observations suggest that it’s only responsible for fruit set of S. adamantium in PESCAN. Key words: Bird pollination, vertebrate-plant interactions, nectar energy content, resource defense, protandry, Eupetomena macroura, Trochilidae. Resumo: Alguns autores sugeriram que por causa da estrutura da inflorescência e biologia floral, aves que pousam na inflorescência são polinizadores mais adequados de espécies de Marcgraviaceae do que beija-flores. -

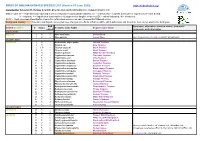

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Body Mass As a Supertrait Linked to Abundance and Behavioral Dominance in Hummingbirds: a Phylogenetic Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aberdeen University Research Archive Received: 7 July 2018 | Revised: 17 October 2018 | Accepted: 8 November 2018 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.4785 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Body mass as a supertrait linked to abundance and behavioral dominance in hummingbirds: A phylogenetic approach Rafael Bribiesca1,2 | Leonel Herrera‐Alsina3 | Eduardo Ruiz‐Sanchez4 | Luis A. Sánchez‐González5 | Jorge E. Schondube2 1Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Unidad de Posgrado, Coordinación del Posgrado en Abstract Ciencias Biológicas, UNAM, Mexico City, Body mass has been considered one of the most critical organismal traits, and its role Mexico in many ecological processes has been widely studied. In hummingbirds, body mass 2Instituto de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad, Universidad Nacional has been linked to ecological features such as foraging performance, metabolic rates, Autónoma de México, Morelia, Mexico and cost of flying, among others. We used an evolutionary approach to test whether 3University of Groningen, Groningen, The body mass is a good predictor of two of the main ecological features of humming‐ Netherlands 4Departamento de Botánica y Zoología, birds: their abundances and behavioral dominance. To determine whether a species Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y was abundant and/or behaviorally dominant, we used information from the literature Agropecuarias, Universidad de Guadalajara, Zapopan, México on 249 hummingbird species. For abundance, we classified a species as “plentiful” if 5Museo de Zoología “Alfonso L. Herrera”, it was described as the most abundant species in at least part of its geographic distri‐ Depto. de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de bution, while we deemed a species to be “behaviorally dominant” when it was de‐ Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, México scribed as pugnacious (notably aggressive).