Avian Distraction Displays: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds

CHAPTER 1 General introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds, sometimes referred to as waders, are birds that rely on coastal beaches, shorelines, estuaries and mudflats, or inland lakes, lagoons and the like for part of, and in some cases all of, their daily and annual requirements, i.e. food and shelter, breeding habitat. They are of the suborder Charadrii and include the curlews, snipe, plovers, sandpipers, stilts, oystercatchers and a number of other species, making up a diverse group of birds. Within Australia, shorebirds account for 10% of all bird species (Lane 1987) and in New South Wales (NSW), this figure increases marginally to 11% (Smith 1991). Of these shorebirds, 45% rely exclusively on coastal habitat (Smith 1991). The majority, however, are either migratory or vagrant species, leaving only five resident species that will permanently inhabit coastal shorelines/beaches within Australia. Australian resident shorebirds include the Beach Stone-curlew (Esacus neglectus), Hooded Plover (Charadrius rubricollis), Red- capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus), Australian Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris) and Sooty Oystercatcher (Haematopus fuliginosus) (Smith 1991, Priest et al. 2002). These species are generally classified as ‘beach-nesting’, nesting on sandy ocean beaches, sand spits and sand islands within estuaries. However, the Sooty Oystercatcher is an island-nesting species, using rocky shores of near- and offshore islands rather than sandy beaches. The plovers may also nest by inland salt lakes. Shorebirds around the globe have become increasingly threatened with the pressure of predation, competition, human encroachment and disturbance and global warming. Populations of birds breeding in coastal areas which also support a burgeoning human population are under the highest threat. -

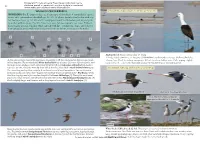

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

FY 2021 Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States BUDGET Department of the Interior JUSTIFICATIONS and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2021 FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE NOTICE: These budget justifications are prepared for the Interior, Environment and Related Agencies Appropriations Subcommittees. Approval for release of the justifications prior to their printing in the public record of the Subcommittee hearings may be obtained through the Office of Budget of the Department of the Interior. Printed on Recycled Paper FY 2021 BUDGET JUSTIFICATION TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fiscal Year 2021 President’s Budget Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................. EX - 1 Organization Chart .................................................................................................. EX - 5 Overview of Fiscal Year 2020 Request ................................................................... EX - 6 Strategic Objective Performance Summary .......................................................... EX - 12 Agency Priority Goals ............................................................................................ EX - 17 Budget at a Glance Table ..................................................................................... BG - 1 Summary of Fixed Costs ......................................................................................... BG - 6 Appropriation: Resource Management Appropriations Language .............................................................................RM -

Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No

BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. Common Name Latin Name Heard RHEIFORMES: Rheidae 1 Lesser Rhea Rhea pennata s TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 2 Elegant Crested-Tinamou Eudromia elegans s ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 3 Southern Screamer Chauna torquata s ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 4 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata s 5 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor s 6 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus s 7 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba s 8 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta s 9 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida s 10 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus s 11 Flightless Steamer-Duck Tachyeres pteneres s 12 White-headed Steamer-Duck Tachyeres leucocephalus s 13 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides s 14 Spectacled Duck Speculanas specularis s 15 Brazilian Teal Amazonetta brasiliensis s 16 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata s 17 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix s 18 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera s 19 Red Shoveler Anas platalea s 20 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica s 21 Silver Teal Anas versicolor s 22 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris s 23 Rosy-billed Pochard Netta peposaca s 24 Black-headed Duck Heteronetta atricapilla s 25 Lake Duck Oxyura vittata s PODICIPEDIFORMES: Podicipedidae 26 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland s 27 Great Grebe Podiceps major s 28 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis s PHOENICOPTERIFORMES: Phoenicopteridae 29 Chilean Flamingo Phoenicopterus chilensis s SPHENISCIFORMES: Spheniscidae 30 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus s 31 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua s 32 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus s PROCELLARIIFORMES: Diomedeidae 33 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris s Page 1 of 6 BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. -

Antipredator Deception in Terrestrial Vertebrates

Current Zoology 60 (1): 16–25, 2014 Antipredator deception in terrestrial vertebrates Tim CARO* Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, and Center of Population Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Abstract Deceptive antipredator defense mechanisms fall into three categories: depriving predators of knowledge of prey’s presence, providing cues that deceive predators about prey handling, and dishonest signaling. Deceptive defenses in terrestrial vertebrates include aspects of crypsis such as background matching and countershading, visual and acoustic Batesian mimicry, active defenses that make animals seem more difficult to handle such as increase in apparent size and threats, feigning injury and death, distractive behaviours, and aspects of flight. After reviewing these defenses, I attempt a preliminary evaluation of which aspects of antipredator deception are most widespread in amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds [Current Zoology 60 (1): 16 25, 2014]. Keywords Amphibians, Birds, Defenses, Dishonesty, Mammals, Prey, Reptiles 1 Introduction homeotherms may increase the distance between prey and the pursuing predator or dupe the predator about the In this paper I review forms of deceptive antipredator flight path trajectory, or both (FitzGibbon, 1990). defenses in terrestrial vertebrates, a topic that has been Last, an antipredator defense may be a dishonest largely ignored for 25 years (Pough, 1988). I limit my signal. Bradbury and Vehrencamp (2011) state that “true scope to terrestrial organisms because lighting condi- deception occurs when a sender produces a signal tions in water are different from those in the air and whose reception will benefit it at the expense of the antipredator strategies often differ in the two environ- receiver regardless of the condition with which the sig- ments. -

Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary Flyway Partnership Report

Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary Flyway Partnership Report Report by The Nature Conservancy For the: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia 27 March 2018 The lead author of this document was David Mehlman of The Nature Conservancy’s Migratory Bird Program, with significant input, editing, and other assistance from James Fitzsimons and Anita Nedosyko of The Nature Conservancy’s Australia Program and Boze Hancock from The Nature Conservancy’s Global Oceans Team. Acknowledgements We thank the Government of South Australia, Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, for funding this work under an agreement with The Nature Conservancy Australia. Helpful advice and comments on various aspects of this project were received from Mark Carey, Tony Flaherty, Rich Fuller, Michaela Heinson, Arkellah Irving, Jason Irving, Micha Jackson, Spike Millington, Chris Purnell, Phil Straw, Connie Warren, Doug Watkins, and Dan Weller. 2 Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................ 4 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Overview of the Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary .............................................................................. -

Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere

Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM) October 2018 Mike Ausman Citation: Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM). 2018. Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere. Unpublished report, Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM). Available at: https://www.shorebirdplan.org/science/program-for-regional-and- international-shorebird-monitoring/. Primary Authors: Matt Reiter, Chair, PRISM, Point Blue Conservation Science, [email protected]; and Brad A. Andres, National Coordinator U.S. Shorebird Conservation Partnership, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, [email protected]. Acknowledgements Both current and previous members of the PRISM Committee, workshop attendees in Panama City and Colorado, and additional reviewers made this document possible: Asociación Calidris – Diana Eusse, Carlos Ruiz Birdlife International – Isadora Angarita BirdsCaribbean – Lisa Sorensen California Department of Fish and Wildlife – Lara Sparks Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Mark Drever, Christian Friis, Ann McKellar, Julie Paquet, Cynthia Pekarik, Adam Smith; Environment and Climate Change Canada, Science and Technology – Paul Smith Centro de Ornitologia y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) – Fernando Angulo El Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada – Eduardo Palacios Fundación Humedales – Daniel Blanco Manomet – Stephen Brown, Rob Clay, Arne Lesterhuis, Brad Winn Museo Nacional de Costa Rica – Ghisselle Alvarado National Audubon Society – Melanie Driscoll, Matt Jeffery, Maki Tazawa Point Blue Conservation Science – Catherine Hickey, Matt Reiter Quetzalli – Salvadora Morales, Orlando Jarquin Red de Observadores de Aves y Vida Silvestre de Chile (ROC) – Heraldo Norambuena SalvaNatura – Alvaro Moises SAVE Brasil – Juliana Bosi Almeida Simon Fraser University – Richard Johnston Sociedad Audubon de Panamá – Karl Kaufman, Rosabel Miró U.S. -

Predators and Anti-Predator Behavior of Wilson's Plover (Charadrius Wilsonia) on Cumberland Island, Georgia

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Fall 2015 Predators and Anti-predator Behavior of Wilson's Plover (Charadrius Wilsonia) on Cumberland Island, Georgia Mary K. Strickland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons Recommended Citation Strickland, M. 2015. Predators and anti-predator behavior of Wilson's Plover (Charadrius Wilsonia) on Cumberland Island, Georgia. MS thesis. Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, Georgia. This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 PREDATORS AND ANTI-PREDATOR BEHAVIOR OF WILSON’S PLOVER (CHARADRIUS WILSONIA) ON CUMBERLAND ISLAND, GEORGIA by MARY STRICKLAND (Under the direction of C. Ray Chandler) ABSTRACT Predation, the major cause of nest failure in birds, is an important factor when considering management and conservation plans. The predator assemblage in an ecosystem changes each year and can cause profound differences in bird nest survival rates. Shorebirds such as Wilson’s Plovers (Charadrius wilsonia) are ideal study species because they are declining and predator control is often a recommended component of management plans. Therefore the objectives of my research were to determine the predator assemblage of the southern end of the beach on Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia, and to determine how three variables affected the display rate and intensity of different anti-predator behaviors of Wilson’s Plover. -

Falkland Islands Species List

Falkland Islands Species List Day Common Name Scientific Name x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 BIRDS* 2 DUCKS, GEESE, & WATERFOWL Anseriformes - Anatidae 3 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus 4 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba 5 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta 6 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida 7 Ruddy-headed Goose Chloephaga rubidiceps 8 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus 9 Falkland Steamer-Duck Tachyeres brachypterus 10 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides 11 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix 12 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos 13 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera 14 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica 15 Silver Teal Anas versicolor 16 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris 17 GREBES Podicipediformes - Podicipedidae 18 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland 19 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis 20 PENGUINS Sphenisciformes - Spheniscidae 21 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus 22 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua Cheesemans' Ecology Safaris Species List Updated: April 2017 Page 1 of 11 Day Common Name Scientific Name x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 23 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus 24 Macaroni Penguin Eudyptes chrysolophus 25 Southern Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome 26 ALBATROSSES Procellariiformes - Diomedeidae 27 Gray-headed Albatross Thalassarche chrysostoma 28 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris 29 Royal Albatross (Southern) Diomedea epomophora epomophora 30 Royal Albatross (Northern) Diomedea epomophora sanfordi 31 Wandering Albatross (Snowy) Diomedea exulans exulans 32 Wandering -

Louis A. Fuertes and the Zoological Art of the 1926–1927 Abyssinian Expedition of the Field Museum of Natural History

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Ornithology Papers in the Biological Sciences 12-9-2008 Louis A. Fuertes and the Zoological Art of the 1926–1927 Abyssinian Expedition of The Field Museum of Natural History Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology Part of the Art Practice Commons, Ornithology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Louis A. Fuertes and the Zoological Art of the 1926–1927 Abyssinian Expedition of The Field Museum of Natural History" (2008). Papers in Ornithology. 44. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Ornithology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Ornithology Papers in the Biological Sciences 12-9-2008 Louis A. Fuertes and the Zoological Art of the 1926–1927 Abyssinian Expedition of The ieldF Museum of Natural History Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology Part of the Art Practice Commons, Ornithology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Louis A. Fuertes and the Zoological Art of the 1926–1927 Abyssinian Expedition of The ieF ld Museum of Natural History" (2008). Papers in Ornithology. 44. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -

Lanius Collurio) Vs

RESEARCH ARTICLE Facing a Clever Predator Demands Clever Responses - Red-Backed Shrikes (Lanius collurio) vs. Eurasian Magpies (Pica pica) Michaela Syrová1,2, Michal Němec1, Petr Veselý1*, Eva Landová3, Roman Fuchs1 1 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 1760, České Budějovice, 37005, Czech Republic, 2 Department of Ethology, Institute of Animal Science in Prague, Přátelství 815, Prague – Uhříněves, 10400, Czech Republic, 3 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Viničná 1594/7, Praha – Nové Město, 12800, Czech Republic * [email protected] a11111 Abstract Red-backed shrikes (Lanius collurio) behave quite differently towards two common nest predators. While the European jay (Garrulus glandarius) is commonly attacked, in the pres- OPEN ACCESS ence of the Eurasian magpie (Pica pica), shrikes stay fully passive. We tested the hypothe- ses that this passive response to the magpie is an alternative defense strategy. Nesting Citation: Syrová M, Němec M, Veselý P, Landová E, Fuchs R (2016) Facing a Clever Predator Demands shrikes were exposed to the commonly attacked European kestrel (Falco tinnunculus)ina Clever Responses - Red-Backed Shrikes (Lanius situation in which i) a harmless domestic pigeon, ii) a commonly attacked European jay, and collurio) vs. Eurasian Magpies (Pica pica). PLoS iii) a non-attacked black-billed magpie are (separately) presented nearby. The kestrel ONE 11(7): e0159432. doi:10.1371/journal. dummy presented together with the magpie dummy was attacked with a significantly lower pone.0159432 intensity than when it was presented with the other intruders (pigeon, jay) or alone. This Editor: Csaba Moskát, Hungarian Academy of means that the presence of the magpie inhibited the shrike’s defense response towards the Sciences, HUNGARY other intruder. -

Sea Lion Island

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 7, 2nd edition, as amended by COP9 Resolution IX.1 Annex B). A 3rd edition of the Handbook, incorporating these amendments, is in preparation and will be available in 2006. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the Official Respondent: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. Joint Nature Conservation Committee DD MM YY Monkstone House City Road Peterborough Designation date Site Reference Number Cambridgeshire PE1 1JY UK Telephone/Fax: +44 (0)1733 – 562 626 / +44 (0)1733 – 555 948 Email: [email protected] Name and address of the compiler of this form: UK Overseas Territories Conservation Forum, 102 Broadway, Peterborough, PE1 4DG, UK 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: Designated: 24 September 2001 3.