Synthesis of Oystercatcher Conservation Assessments: General Lessons and Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Australian Bird Notes 85: 8

WesternWestern AustralianAustralian BirdBird NotesNotes Quarterly Newsletter of Birds Australia Western Australia Inc CONSERVATION THROUGH KNOWLEDGE (a division of Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union) No 117 March 2006 ISSN 1445-3983 C on t e n t s Observations ........................................ p6 Notices.................................................p20 Coming Events ....................................p27 BAWA Reports...................................... p8 New Members......................................p22 Crossword Answers ...........................p31 BAWA Projects................................... p10 Country Groups ..................................p23 Opportunities for Volunteers .............p32 Members’ Contributions.................... p14 Excursion Reports..............................p23 Calendar of Events..............................p32 Crossword........................................... p19 Observatories......................................p26 SOOTY OYSTERCATCHER SITES IN SOUTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA For more than ten years now, members from Birds Australia rocky coastline. Sites where Sooty Oystercatcher sightings WA have been involved in Hooded Plover surveys. During have been recorded are shown in Table 1. this time, much information has been gained on Hooded Plovers, but other data have also been gathered. Coastal distribution of Sooty Oystercatchers from Perth to Eyre Observers were asked to complete a survey sheet and record sightings of other wader species. Consequently, in addition to Perth Hooded -

American Oystercatcher

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Haematopus palliatus (American Oystercatcher) Priority 3 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Haematopodidae (Oystercatchers) General comments: First nesting record in Maine - 1994. 4 - 8 breeding pairs in Maine, range expansion, Northern Atlantic population 11,000 and considered stable. Listed as Critical risk category because of high vulnerability to climate change - Gilbrathe et al. 2014. Species Conservation Range Maps for American Oystercatcher: Town Map: Haematopus palliatus_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Haematopus palliatus_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: Haematopus palliatus is listed as a species of Special Concern in Maine. Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: United States Shorebird Conservation Plan: Species of High Concern North Atlantic Regional Shorebird Plan: Highly Imperiled United States Birds of Conservation Concern: Bird of Conservation Concern in Bird Conservation Regions 14 and/or 30: Yes High Climate Change Vulnerability: Vulnerability: 3, Confidence: High, Reviewers: Decided in Workshop (W) Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to American Oystercatcher: Formation Name Cliff & Rock Macrogroup Name Rocky Coast Formation Name Intertidal Macrogroup Name Intertidal -

Black Oystercatcher

Alaska Species Ranking System - Black Oystercatcher Black Oystercatcher Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Haematopus bachmani Review Status: Peer-reviewed Version Date: 08 April 2019 Conservation Status NatureServe: Agency: G Rank:G5 ADF&G: Species of Greatest Conservation Need IUCN: Audubon AK: S Rank: S2S3B,S2 USFWS: Bird of Conservation Concern BLM: Final Rank Conservation category: V. Orange unknown status and either high biological vulnerability or high action need Category Range Score Status -20 to 20 0 Biological -50 to 50 11 Action -40 to 40 -4 Higher numerical scores denote greater concern Status - variables measure the trend in a taxon’s population status or distribution. Higher status scores denote taxa with known declining trends. Status scores range from -20 (increasing) to 20 (decreasing). Score Population Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Suspected stable (ASG 2019; Cushing et al. 2018), but data are limited and do not encompass this species' entire range. We therefore rank this question as Unknown. Distribution Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Habitat is dynamic and subject to change as a result of geomorphic and glacial processes. For example, numbers expanded on Middleton Island after the 1964 earthquake (Gill et al. 2004). Status Total: 0 Biological - variables measure aspects of a taxon’s distribution, abundance and life history. Higher biological scores suggest greater vulnerability to extirpation. Biological scores range from -50 (least vulnerable) to 50 (most vulnerable). Score Population Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -2 Uncertain. The global population is estimated at 11,000 individuals, of which 45%-70% breed in Alaska (ASG 2019). -

Pyura Doppelgangera to Support Regional Response Decisions

REPORT NO. 2480 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE SEA SQUIRT PYURA DOPPELGANGERA TO SUPPORT REGIONAL RESPONSE DECISIONS CAWTHRON INSTITUTE | REPORT NO. 2480 JUNE 2014 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE SEA SQUIRT PYURA DOPPELGANGERA TO SUPPORT REGIONAL RESPONSE DECISIONS LAUREN FLETCHER Prepared for Marlborough District Council CAWTHRON INSTITUTE 98 Halifax Street East, Nelson 7010 | Private Bag 2, Nelson 7042 | New Zealand Ph. +64 3 548 2319 | Fax. +64 3 546 9464 www.cawthron.org.nz REVIEWED BY: APPROVED FOR RELEASE BY: Javier Atalah Chris Cornelisen ISSUE DATE: 3 June 2014 RECOMMENDED CITATION: Fletcher LM 2014. Background information on the sea squirt, Pyura doppelgangera to support regional response decisions. Prepared for Marlborough District Council. Cawthron Report No. 2480. 30 p. © COPYRIGHT: Cawthron Institute. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part without further permission of the Cawthron Institute, provided that the author and Cawthron Institute are properly acknowledged. CAWTHRON INSTITUTE | REPORT NO. 2480 JUNE 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The non-indigenous solitary sea squirt, Pyura doppelgangera (herein Pyura), was first detected in New Zealand in 2007 after a large population was found in the very north of the North Island. A delimitation survey by the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) during October 2009 found established populations at 21 locations within the region. It is not known how long Pyura has been present in New Zealand, although it is not believed to be a recent introduction. Pyura is an aggressive interspecific competitor for primary space. As such, this species may negatively impact native green-lipped mussel beds present, with associated impacts to key social and cultural values. -

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5635/docket-no-fws-hq-es-2019-0009-ff09e21000-fxes11190900000-167-75635.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/10/2019 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2019-21478, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Domestic and Foreign Species That Are Candidates for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notification of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of review. SUMMARY: In this candidate notice of review (CNOR), we, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), present an updated list of plant and animal species that we regard as candidates for or have proposed for addition to the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended. Identification of candidate species can assist environmental planning efforts by providing advance notice of potential listings, and by allowing landowners and resource managers to alleviate threats and thereby possibly remove the need to list species as endangered or threatened. Even if we subsequently list a candidate species, the early notice provided here could result in more options for species management and recovery by prompting earlier candidate conservation measures to alleviate threats to the species. This document also includes our findings on resubmitted petitions and describes our 1 progress in revising the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants (Lists) during the period October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2018. -

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds

CHAPTER 1 General introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds, sometimes referred to as waders, are birds that rely on coastal beaches, shorelines, estuaries and mudflats, or inland lakes, lagoons and the like for part of, and in some cases all of, their daily and annual requirements, i.e. food and shelter, breeding habitat. They are of the suborder Charadrii and include the curlews, snipe, plovers, sandpipers, stilts, oystercatchers and a number of other species, making up a diverse group of birds. Within Australia, shorebirds account for 10% of all bird species (Lane 1987) and in New South Wales (NSW), this figure increases marginally to 11% (Smith 1991). Of these shorebirds, 45% rely exclusively on coastal habitat (Smith 1991). The majority, however, are either migratory or vagrant species, leaving only five resident species that will permanently inhabit coastal shorelines/beaches within Australia. Australian resident shorebirds include the Beach Stone-curlew (Esacus neglectus), Hooded Plover (Charadrius rubricollis), Red- capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus), Australian Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris) and Sooty Oystercatcher (Haematopus fuliginosus) (Smith 1991, Priest et al. 2002). These species are generally classified as ‘beach-nesting’, nesting on sandy ocean beaches, sand spits and sand islands within estuaries. However, the Sooty Oystercatcher is an island-nesting species, using rocky shores of near- and offshore islands rather than sandy beaches. The plovers may also nest by inland salt lakes. Shorebirds around the globe have become increasingly threatened with the pressure of predation, competition, human encroachment and disturbance and global warming. Populations of birds breeding in coastal areas which also support a burgeoning human population are under the highest threat. -

Scottish Birds 22: 9-19

Scottish Birds THE JOURNAL OF THE SOC Vol 22 No 1 June 2001 Roof and ground nesting Eurasian Oystercatchers in Aberdeen The contrasting status of Ring Ouzels in 2 areas of upper Deeside The distribution of Crested Tits in Scotland during the 1990s Western Capercaillie captures in snares Amendments to the Scottish List Scottish List: species and subspecies Breeding biology of Ring Ouzels in Glen Esk Scottish Birds The Journal of the Scottish Ornithologists' Club Editor: Dr S da Prato Assisted by: Dr I Bainbridge, Professor D Jenkins, Dr M Marquiss, Dr J B Nelson, and R Swann Business Editor: The Secretary sac, 21 Regent Terrace Edinburgh EH7 5BT (tel 0131-5566042, fax 0131 5589947, email [email protected]). Scottish Birds, the official journal of the Scottish Ornithologists' Club, publishes original material relating to ornithology in Scotland. Papers and notes should be sent to The Editor, Scottish Birds, 21 Regent Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 SBT. Two issues of Scottish Birds are published each year, in June and in December. Scottish Birds is issued free to members of the Scottish Ornithologists' Club, who also receive the quarterly newsletter Scottish Bird News, the annual Scottish Bird Report and the annual Raplor round up. These are available to Institutions at a subscription rate (1997) of £36. The Scottish Ornithologists' Club was formed in 1936 to encourage all aspects of ornithology in Scotland. It has local branches which meet in Aberdeen, Ayr, the Borders, Dumfries, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Inverness, New Galloway, Orkney, St Andrews, Stirling, Stranraer and Thurso, each with its own programme of field meetings and winter lectures. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

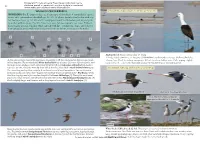

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Introduction

BlackOystercatcher — BirdsofNorthAmericaOnline Page1of2 From the CORNELL LAB OF ORNITHOLOGY and the AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS'UNION. species or keywords Search Home Species Subscribe News & Info FAQ Already a subscriber? Sign in Don'thave a subscription? Subscribe Now Black Oystercatcher Haematopus bachmani Order CHARADRIIFORMES –Family HAEMATOPODIDAE Issue No.155 Authors:Andres, Brad A.,and Gary A.Falxa • Articles • Multimedia • References Articles Introduction Welcome to the Birds of North America Online! Welcome to BNA Online, the leading source of life history information for North American breeding birds.This free, Distinguishing Characteristics courtesy preview is just the first of 14articles that provide detailed life history information including Distribution, Migration, Distribution Habitat, Food Habits, Sounds, Behavior and Breeding.Written by acknowledged experts on each species, there is also a comprehensive bibliography of published research on the species. Systematics Migration A subscription is needed to access the remaining articles for this and any other species.Subscription rates start as low as $5USD for 30days of complete access to the resource.To subscribe, please visit the Cornell Lab of Ornithology E-Store. Habitat Food Habits If you are already a current subscriber, you will need to sign in with your login information to access BNA normally. Sounds Subscriptions are available for as little as $5for 30days of full access!If you would like to subscribe to BNA Online, just Behavior visit the Cornell Lab of Ornithology E-Store. Breeding Introduction Demography and Populations Conservation and Management Appearance Measurements Priorities for Future Research Acknowledgments About the Author(s) Black Oystercatcher in flight, Pt.Pinos, Monterey, California, 18February 2007. http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/155/articles/introduction 11/14/2015 BlackOystercatcher — BirdsofNorthAmericaOnline Page2of2 Fig.1.Distribution of the Black Oystercatcher. -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Biden Urged to Protect 19 Foreign Species

Via electronic and certified mail February 3, 2021 Scott de la Vega Director Acting Secretary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street, NW 1849 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20240 Washington, DC 20240 [email protected] Don Morgan Chief, Branch of Delisting and Foreign Martha Williams Species, Ecological Services Principal Deputy Director 5275 Leesburg Pike U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Falls Church, VA 22041-3808 1849 C Street, NW [email protected] Washington, DC 20240 [email protected] Re: Sixty-Day Notice of Intent to Sue for Failing to Make Timely 12-Month Findings on Foreign Candidate Species in Violation of the Endangered Species Act Dear Acting Secretary de la Vega, Director of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Principal Deputy Director Williams, and Chief Morgan, On behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity (Center), we write to notify you that the U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (together, the Service) are currently in violation of Section 4 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for failing to make required 12-month findings on 19 foreign candidate species (Table 1). Section 4(b)(3) of the ESA requires the Service to determine if ESA protections are warranted for a species within 12 months of previously finding that listing was precluded by other pending proposals.1 Here, the Service found listing of 19 foreign species was warranted but precluded on October 10, 2019, and thus new listing determinations were due by October 10, 2020—nearly four months ago.