Investigating the Possible Change in Breeding Strategy of African Black Oystercatchers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5635/docket-no-fws-hq-es-2019-0009-ff09e21000-fxes11190900000-167-75635.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/10/2019 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2019-21478, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Domestic and Foreign Species That Are Candidates for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notification of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of review. SUMMARY: In this candidate notice of review (CNOR), we, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), present an updated list of plant and animal species that we regard as candidates for or have proposed for addition to the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended. Identification of candidate species can assist environmental planning efforts by providing advance notice of potential listings, and by allowing landowners and resource managers to alleviate threats and thereby possibly remove the need to list species as endangered or threatened. Even if we subsequently list a candidate species, the early notice provided here could result in more options for species management and recovery by prompting earlier candidate conservation measures to alleviate threats to the species. This document also includes our findings on resubmitted petitions and describes our 1 progress in revising the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants (Lists) during the period October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2018. -

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds

CHAPTER 1 General introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds, sometimes referred to as waders, are birds that rely on coastal beaches, shorelines, estuaries and mudflats, or inland lakes, lagoons and the like for part of, and in some cases all of, their daily and annual requirements, i.e. food and shelter, breeding habitat. They are of the suborder Charadrii and include the curlews, snipe, plovers, sandpipers, stilts, oystercatchers and a number of other species, making up a diverse group of birds. Within Australia, shorebirds account for 10% of all bird species (Lane 1987) and in New South Wales (NSW), this figure increases marginally to 11% (Smith 1991). Of these shorebirds, 45% rely exclusively on coastal habitat (Smith 1991). The majority, however, are either migratory or vagrant species, leaving only five resident species that will permanently inhabit coastal shorelines/beaches within Australia. Australian resident shorebirds include the Beach Stone-curlew (Esacus neglectus), Hooded Plover (Charadrius rubricollis), Red- capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus), Australian Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris) and Sooty Oystercatcher (Haematopus fuliginosus) (Smith 1991, Priest et al. 2002). These species are generally classified as ‘beach-nesting’, nesting on sandy ocean beaches, sand spits and sand islands within estuaries. However, the Sooty Oystercatcher is an island-nesting species, using rocky shores of near- and offshore islands rather than sandy beaches. The plovers may also nest by inland salt lakes. Shorebirds around the globe have become increasingly threatened with the pressure of predation, competition, human encroachment and disturbance and global warming. Populations of birds breeding in coastal areas which also support a burgeoning human population are under the highest threat. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

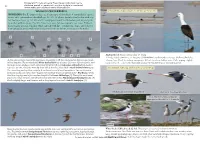

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Biden Urged to Protect 19 Foreign Species

Via electronic and certified mail February 3, 2021 Scott de la Vega Director Acting Secretary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street, NW 1849 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20240 Washington, DC 20240 [email protected] Don Morgan Chief, Branch of Delisting and Foreign Martha Williams Species, Ecological Services Principal Deputy Director 5275 Leesburg Pike U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Falls Church, VA 22041-3808 1849 C Street, NW [email protected] Washington, DC 20240 [email protected] Re: Sixty-Day Notice of Intent to Sue for Failing to Make Timely 12-Month Findings on Foreign Candidate Species in Violation of the Endangered Species Act Dear Acting Secretary de la Vega, Director of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Principal Deputy Director Williams, and Chief Morgan, On behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity (Center), we write to notify you that the U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (together, the Service) are currently in violation of Section 4 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for failing to make required 12-month findings on 19 foreign candidate species (Table 1). Section 4(b)(3) of the ESA requires the Service to determine if ESA protections are warranted for a species within 12 months of previously finding that listing was precluded by other pending proposals.1 Here, the Service found listing of 19 foreign species was warranted but precluded on October 10, 2019, and thus new listing determinations were due by October 10, 2020—nearly four months ago. -

Federal Register/Vol. 74, No. 154/Wednesday, August 12, 2009

40540 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 154 / Wednesday, August 12, 2009 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR questions concerning this notice to the precluded finding on a petition to list above address. means that listing is warranted, but that Fish and Wildlife Service FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: the immediate proposal and timely Chief, Branch of Listing, Endangered promulgation of a final regulation is 50 CFR Part 17 Species Program, (see ADDRESSES); by precluded by higher priority listing [Docket No. FWS-R9-ES-2009-0057] telephone at 703-358-2171; or by actions. In making a warranted-but [90100 16641FLA-B6] facsimile at 703-358-1735). Persons who precluded finding under the Act, the use a telecommunications device for the Service must demonstrate that Endangered and Threatened Wildlife deaf (TDD) may call the Federal expeditious progress is being made to and Plants; Annual Notice of Findings Information Relay Service (FIRS) at 800- add and remove species from the lists of on Resubmitted Petitions for Foreign 877-8339. endangered and threatened wildlife and Species; Annual Description of SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: plants. Progress on Listing Actions Pursuant to section 4(b)(3)(C)(i) of the Background Act, when, in response to a petition, we AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, The Endangered Species Act of 1973, find that listing a species is warranted Interior. but precluded, we must make a new 12– ACTION: Notice of review. as amended (Act) (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.), provides two mechanisms for month finding annually until we SUMMARY: In this notice of review, we considering species for listing. -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 200/Monday, October 17, 2016

Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 200 / Monday, October 17, 2016 / Proposed Rules 71457 for the relevant maintenance period in attainment of the 2008 ozone NAAQS Technology Transfer and Advancement with mobile source emissions at the through 2030. Finally, EPA finds Act of 1995 (15 U.S.C. 272 note) because levels of the MVEBs. adequate and is proposing to approve application of those requirements would the newly-established 2020 and 2030 be inconsistent with the CAA; and C. What is a safety margin? MVEBs for the Cleveland area. • Does not provide EPA with the A ‘‘safety margin’’ is the difference discretionary authority to address, as VII. Statutory and Executive Order between the attainment level of appropriate, disproportionate human Reviews emissions (from all sources) and the health or environmental effects, using projected level of emissions (from all Under the CAA, redesignation of an practicable and legally permissible sources) in the maintenance plan. As area to attainment and the methods, under Executive Order 12898 noted in Table 11, the emissions in the accompanying approval of a (59 FR 7629, February 16, 1994). Cleveland area are projected to have maintenance plan under section In addition, the SIP is not approved safety margins of 117.22 TPSD for NOX 107(d)(3)(E) are actions that affect the to apply on any Indian reservation land and 28.48 TPSD for VOC in 2030 (the status of a geographical area and do not or in any other area where EPA or an total net change between the attainment impose any additional regulatory Indian tribe has demonstrated that a year, 2014, emissions and the projected requirements on sources beyond those tribe has jurisdiction. -

FY 2021 Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States BUDGET Department of the Interior JUSTIFICATIONS and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2021 FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE NOTICE: These budget justifications are prepared for the Interior, Environment and Related Agencies Appropriations Subcommittees. Approval for release of the justifications prior to their printing in the public record of the Subcommittee hearings may be obtained through the Office of Budget of the Department of the Interior. Printed on Recycled Paper FY 2021 BUDGET JUSTIFICATION TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fiscal Year 2021 President’s Budget Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................. EX - 1 Organization Chart .................................................................................................. EX - 5 Overview of Fiscal Year 2020 Request ................................................................... EX - 6 Strategic Objective Performance Summary .......................................................... EX - 12 Agency Priority Goals ............................................................................................ EX - 17 Budget at a Glance Table ..................................................................................... BG - 1 Summary of Fixed Costs ......................................................................................... BG - 6 Appropriation: Resource Management Appropriations Language .............................................................................RM -

Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No

BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. Common Name Latin Name Heard RHEIFORMES: Rheidae 1 Lesser Rhea Rhea pennata s TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 2 Elegant Crested-Tinamou Eudromia elegans s ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 3 Southern Screamer Chauna torquata s ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 4 White-faced Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna viduata s 5 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor s 6 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus s 7 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba s 8 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta s 9 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida s 10 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus s 11 Flightless Steamer-Duck Tachyeres pteneres s 12 White-headed Steamer-Duck Tachyeres leucocephalus s 13 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides s 14 Spectacled Duck Speculanas specularis s 15 Brazilian Teal Amazonetta brasiliensis s 16 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata s 17 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix s 18 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera s 19 Red Shoveler Anas platalea s 20 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica s 21 Silver Teal Anas versicolor s 22 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris s 23 Rosy-billed Pochard Netta peposaca s 24 Black-headed Duck Heteronetta atricapilla s 25 Lake Duck Oxyura vittata s PODICIPEDIFORMES: Podicipedidae 26 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland s 27 Great Grebe Podiceps major s 28 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis s PHOENICOPTERIFORMES: Phoenicopteridae 29 Chilean Flamingo Phoenicopterus chilensis s SPHENISCIFORMES: Spheniscidae 30 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus s 31 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua s 32 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus s PROCELLARIIFORMES: Diomedeidae 33 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris s Page 1 of 6 BIRD CHECKLIST Leaders: Steve Ogle Eagle-Eye Tours 2018 Patagonia Wildlife Safari Paul Prior BIRD SPECIES - Total 177 Seen/ No. -

Supplementary Table 3. List of Highly Threatened Predicted Eradication Beneficiaries

Supplementary Table 3. List of highly threatened predicted eradication beneficiaries. * indicates populations found in both predicted beneficiaries and demonstrated beneficiaries analysis. Island name Country or Territory Common name Scientific name Animal Type IUCN Red List Status Amsterdam French Southern Territories Amsterdam albatross Diomedea Seabird CR amsterdamensis Amsterdam French Southern Territories Northern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes moseleyi Seabird EN Amsterdam French Southern Territories Sooty albatross Phoebetria fusca Seabird EN Amsterdam French Southern Territories Indian yellow-nosed albatross Thalassarche carteri Seabird EN Anacapa East United States Ashy storm-petrel Oceanodroma Seabird EN homochroa Anacapa Middle United States Ashy storm-petrel Oceanodroma Seabird EN homochroa Anacapa West United States Ashy storm-petrel* Oceanodroma Seabird EN homochroa Anatahan Northern Mariana Islands Micronesian megapode Megapodius laperouse Landbird EN Anatahan Northern Mariana Islands Marianas flying fox Pteropus mariannus Mammal EN Anchor New Zealand Yellowhead (mohua) Mohoua ochrocephala Landbird EN Anchor New Zealand Kakapo Strigops habroptila Landbird CR Aride Seychelles Seychelles magpie-robin* Copsychus sechellarum Landbird EN Aride Seychelles Seychelles wolf snake Lycognathophis Reptile EN seychellensis Attu United States Marbled murrelet Brachyramphus Seabird EN marmoratus Baltra Ecuador Galápagos martin Progne modesta Landbird EN Bay Cay Turks And Caicos Islands Turks and Caicos ground Cyclura carinata Reptile CR iguana Bench New Zealand Yellow-eyed penguin Megadyptes antipodes Seabird EN Bernier Australia Banded hare wallaby Lagostrophus fasciatus Mammal EN Bernier Australia Western barred bandicoot Perameles bougainville Mammal EN Big South Cape New Zealand New Zealand greater short- Mystacina robusta Mammal CR tailed bat Breaksea New Zealand Yellowhead (mohua)* Mohoua ochrocephala Landbird EN Browns New Zealand New Zealand dotterel Charadrius obscurus Landbird EN Buck (St. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 150/Monday, August 9, 2021

43470 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 150 / Monday, August 9, 2021 / Proposed Rules How can I get copies of the proposed digital television service, including Federal Communications Commission. action and other related information? propagation characteristics that allow Thomas Horan, EPA has established a docket for this undesired signals and noise to be Chief of Staff, Media Bureau. receivable at relatively far distances and action under Docket ID No. EPA–HQ– Proposed Rule OAR–2021–0208. EPA has also nearby electrical devices to cause developed a website for this proposal, interference. According to the For the reasons discussed in the which is available at https:// Petitioner, it has received numerous preamble, the Federal Communications www.epa.gov/regulations-emissions- complaints of poor or no reception from Commission proposes to amend 47 CFR vehicles-and-engines/proposed-rule- viewers, and explains the importance of part 73 as follows: revise-existing-national-ghg-emissions. a strong over-the-air signal in the Portland area during emergencies, PART 73—RADIO BROADCAST Please refer to the notice of proposed SERVICES rulemaking for detailed information on when, it states, cable and satellite accessing information related to the service may go out of operation. Finally, ■ 1. The authority citation for part 73 proposal. the Petitioner demonstrated that the continues to read as follows: channel 21 noise limited contour would Dated: July 29, 2021. fully encompass the existing channel 12 Authority: 47 U.S.C. 154, 155, 301, 303, William Charmley, contour, and an analysis using the 307, 309, 310, 334, 336, 339. Director, Assessment and Standards Division, Commission’s TVStudy software ■ 2. -

Avian Distraction Displays: a Review

1 Running head: Distraction displays review 2 Avian distraction displays: a review 3 4 ROSALIND K. HUMPHREYS1* & GRAEME D. RUXTON1 5 1School of Biology, University of St Andrews, Dyer's Brae House, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9TH, UK 6 *Corresponding author. 7 Email: [email protected] 8 ORCiD: Rosalind K. Humphreys: 0000-0001-7266-7523, Graeme D. Ruxton: 0000-0001-8943-6609 9 10 Distraction displays are conspicuous behaviours functioning to distract a predator’s attention away 11 from the displayer’s nest or young, thereby reducing the chance of offspring being discovered and 12 predated. Distraction is one of the riskier parental care tactics, as its success derives from the 13 displaying parent becoming the focus of a predator’s attention. Such displays are prominent in birds, 14 primarily shorebirds, but the last comprehensive review of distraction was in 1984. Our review aims 15 to provide an updated synthesis of what is known about distraction displays in birds, and to open up 16 new areas of study by highlighting some of the key avenues to explore and the broadened ecological 17 perspectives that could be adopted in future research. We begin by drawing attention to the 18 flexibility of form that distraction displays can take and providing an overview of the different avian 19 taxa known to use anti-predator distraction displays, also examining species-specific sex differences 20 in use. We then explore the adaptive value and evolution of distraction displays, before considering 21 the variation seen in the timing of their use over a reproductive cycle. An evaluation of the efficacy 22 of distraction compared with alternative anti-predator tactics is then conducted via a cost-benefit 23 analysis. -

Conserving Shorebirds in Human-Dominated Landscapes Micha Victoria Jackson Bachelor of Arts, Environmental Studies

Conserving shorebirds in human-dominated landscapes Micha Victoria Jackson Bachelor of Arts, Environmental Studies ORCID: 0000-0002-5150-2962 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2020 School of Biological Sciences i Abstract Wetlands support biodiversity and provide critical ecosystem services but have been severely impacted by human activity. Shorebirds are a diverse group of waterbirds that usually forage in shallow water, making them highly dependent on wetlands. Coastal shorebirds are increasingly threatened in the East Asian-Australasian Flyway where coastlines are heavily developed and wetlands have been extensively modified and degraded. In this human-dominated landscape, shorebirds sometimes aggregate in artificial wetlands associated with human production activities including agriculture, aquaculture and salt production. However, it is unknown whether artificial habitat use is widespread by shorebirds across the flyway, if such habitats could help to offset negative population trends, or how artificial habitats should be managed alongside natural habitats to achieve conservation outcomes. This thesis investigates the use of artificial and natural habitats by shorebirds in heavily developed coastal regions of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, and suggests conservation and management actions in this setting. Chapter 2 presents the first large-scale review of coastal artificial habitat use by shorebirds in the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. Analysing data from multiple monitoring programs and the literature, it shows that 83 shorebird species have occurred on more than 170 artificial sites of eight different land uses throughout the flyway, including 36 species in internationally important numbers. However, occurrence and foraging on artificial habitats is uneven among species, and different land uses support varying abundances and species diversity.