Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis of an Australian Wildlife Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translocations and Fauna Reconstruction Sites: Western Shield Review—February 2003

108 Conservation Science W. Aust. 5 (2) : 108–121P.R. Mawson (2004) Translocations and fauna reconstruction sites: Western Shield review—February 2003 PETER R. MAWSON1 1Senior Zoologist, Wildlife Branch , Department of Conservation and Land Management, Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983. [email protected] SUMMARY address this problem, but will result in slower progress towards future milestones for some species. The captive-breeding of western barred bandicoots Objectives has also been hampered by disease issues, but this problem is dealt with in more detail elsewhere in this edition (see The objectives of Western Shield with regard to fauna Morris et al. this issue). translocations were to re-introduce a range of native fauna There is a clear need to better define criteria that will species to a number of sites located primarily in the south- be used to determine the success or failure of translocation west of Western Australia. At some sites whole suites of programs, and for those same criteria to be included in fauna needed to be re-introduced, while at others only Recovery Plans and Interim Recovery Plans. one or a few species were targeted for re-introduction. A small number of the species that are currently the Integration of Western Shield activities with recovery subject of captive-breeding programs and or translocations actions and co-operative arrangements with community do not have Recovery Plans or Interim Recovery Plans, groups, wildlife carers, wildlife sanctuaries, Perth Zoo and contrary to CALM Policy Statement No. 50. In other educational outcomes were other key objectives. cases the priorities by which plans are written does not Achievements reflect the IUCN rank assigned those species by the Western Australian Threatened Species Scientific The fauna translocation objectives defined in the founding Committee. -

2008-09, the Zoo’S Fundraising Program, Wildlife During the Year the Board Also Commenced an Continues to Go from Strength to Strength

contents Zoological Parks Authority ANNUAL REPORT 2009 Zoological Parks Authority ANNUAL REPORT 2009 contents Our Purpose To secure long term populations of species in natural environments while engaging the community in global conservation action. Perth Zoo Location In line with State Government requirements, This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in 20 Labouchere Road Perth Zoo’s annual report – the Zoological whole or in part for study or training purposes if Parks Authority Annual Report 2008-2009 – is an acknowledgment of the source is included. South Perth, Western Australia. published in an electronic format with limited Such use must not be for the purpose of sale or Postal Address use of graphics and illustrations to help minimise commercial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright download times. Act, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system PO Box 489 or transmission in any form by any means of Perth Zoo encourages people to use recycled South Perth any part of the work other than for the purposes paper if they print a copy of this report or above is not permitted without prior written Western Australia 6951 sections of it. For the convenience of readers and authorisation from the Zoological Parks Authority. to minimise download times and print outs, the Contact Numbers annual report has been presented in chapters, as Information about this report and requests and Telephone (08) 9474 0444 well as the entire document. The annual report is inquiries concerning reproduction should be Facsimile (08) 9474 4420 presented in PDF format. All sections, except the addressed to: financial statements, are also presented in Word [email protected] Debra Read format. -

Download the Annual Report 2019-2020

Leading � rec�very Annual Report 2019–2020 TARONGA ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 A SHARED FUTURE � WILDLIFE AND PE�PLE At Taronga we believe that together we can find a better and more sustainable way for wildlife and people to share this planet. Taronga recognises that the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems are the life support systems for our own species' health and prosperity. At no time in history has this been more evident, with drought, bushfires, climate change, global pandemics, habitat destruction, ocean acidification and many other crises threatening natural systems and our own future. Whilst we cannot tackle these challenges alone, Taronga is acting now and working to save species, sustain robust ecosystems, provide experiences and create learning opportunities so that we act together. We believe that all of us have a responsibility to protect the world’s precious wildlife, not just for us in our lifetimes, but for generations into the future. Our Zoos create experiences that delight and inspire lasting connections between people and wildlife. We aim to create conservation advocates that value wildlife, speak up for nature and take action to help create a future where both people and wildlife thrive. Our conservation breeding programs for threatened and priority wildlife help a myriad of species, with our program for 11 Legacy Species representing an increased commitment to six Australian and five Sumatran species at risk of extinction. The Koala was added as an 11th Legacy Species in 2019, to reflect increasing threats to its survival. In the last 12 months alone, Taronga partnered with 28 organisations working on the front line of conservation across 17 countries. -

Numbat (Myrmecobius Fasciatus) Recovery Plan

Numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) Recovery Plan Wildlife Management Program No. 60 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife February 2017 Wildlife Management Program No. 60 Numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) Recovery Plan February 2017 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983 Foreword Recovery plans are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Parks and Wildlife Corporate Policy Statement No. 35; Conserving Threatened and Ecological Communities (DPaW 2015a), Corporate Guidelines No. 35; Listing and Recovering Threatened Species and Ecological Communities (DPaW 2015b), and the Australian Government Department of the Environment’s Recovery Planning Compliance Checklist for Legislative and Process Requirements (Department of the Environment 2014). Recovery plans outline the recovery actions that are needed to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. Recovery plans are a partnership between the Department of the Environment and Energy and the Department of Parks and Wildlife. The Department of Parks and Wildlife acknowledges the role of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and the Department of the Environment and Energy in guiding the implementation of this recovery plan. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds necessary to implement actions are subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. This recovery plan was approved by the Department of Parks and Wildlife, Western Australia. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in status of the taxon or ecological community, and the completion of recovery actions. -

Perth Zoo Annual Report 2019-20

2020 GOVERNMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Perth Zoo Location In line with State Government requirements, This work is copyright. It may be reproduced 20 Labouchere Road Perth Zoo’s annual report – the Zoological in whole or in part for study or training South Perth, Western Australia 6151 Parks Authority Annual Report 2019-20 – purposes if an acknowledgment of the is published in an electronic format. Perth Zoo source is included. Such use must not Postal Address encourages people to use recycled paper if be for the purpose of sale or commercial PO Box 489 printing a copy of the report. exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act South Perth, Western Australia 6951 For the convenience of readers and to 1968, reproduction, storage in a retrieval minimise download times and print outs, the system or transmission in any form by any Contact Details annual report has been presented in individual means of any part of the work other than for Telephone (08) 9474 0444 chapters, as well as an entire document. the purposes above is not permitted without The annual report is presented in PDF format. prior written authorisation from the Zoological Facsimile (08) 9474 4420 All sections, except the financial statements, Parks Authority. are also presented in Word format. [email protected] Information about this report and requests www.perthzoo.wa.gov.au Zoological Parks Authority Annual Report and inquiries concerning reproduction should 2019-20 be addressed to: © Zoological Parks Authority 2020 Danielle Henry, Media and Communications Manager Perth -

Dexter the Courageous Koala Is Suitable for Readers from Year 5 Up, Although Mature, Capable Readers in Years 3 and 4 Will Also Find Much to Enjoy

Dexter The Courageous Koala By Jesse Blackadder Book Summary: Ashley can’t wait to bring home the puppy she’s been promised —but then Dad loses his job, and her parents can’t afford an extra mouth to feed. Heart-broken, Ashley reluctantly goes off to spend the school holidays with an aunt she barely knows—eccentric Micky, who lives in an isolated spot on the north coast of NSW and who cares for injured koalas. Within hours of arriving, the road into Micky’s house is cut off by rising flood waters, then a wild storm brings a blackout and some serious damage to Micky’s house and garden. Worse still, trees from a nearby koala colony have come down in the storm, and Ashley must risk life and limb to save an injured koala and her joey. Curriculum Areas and Key Learning Outcomes: Dexter the Courageous Koala is suitable for readers from Year 5 up, although mature, capable readers in Years 3 and 4 will also find much to enjoy. ACELT1609,ACELT1795,ACELT1610 ISBN: 9780733331787 ACELY1698,ACELY1701,ACELY1703 eBook 9781743098202 ACELY1704,ACELT1613,ACELT1800 ACELY1710,ACSSU043,ACSSU094 Notes by: Judith Ridge ACHCK027,ACHGK030,ACHGK028 Appropriate Ages: 8-13 These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Page 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jesse Blackadder is an award-winning author for children and adults. She lives on the far north coast of NSW—the same area that Dexter the Courageous Koala is set—where she shares a large garden with a variety of wildlife, including passing koalas. -

Health and Disease Status in a Threatened Marsupial, the Quokka (Setonix Brachyurus)

Health and disease status in a threatened marsupial, the quokka (Setonix brachyurus) Pedro Martínez-Pérez Veterinarian (Hons), MVS Conservation Medicine This thesis was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Wildlife Veterinary Studies, Murdoch University School of Veterinary and Life Sciences Murdoch University Murdoch, Western Australia January 2016 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content, work which has not been previously submitted for a degree at any tertiary educational institution. _______________________________________________ Pedro A. Martínez-Pérez I Abstract Between 1901 and 1931, there were at least six anecdotal records of disease outbreaks in mainland quokkas (Setonix brachyurus) that were associated with mass. This time period pre-dates the arrival of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes). Despite these outbreaks, little or no research has been carried out to establish health and disease baseline data of the fragmented and scattered, extant populations. Epidemiological data was determined for a range of potential pathogens, and established physiological reference intervals of apparently healthy, wild quokkas on Rottnest Island and mainland locations. There were significant differences between Rottnest Island and mainland quokkas. Rottnest Island animals had haemograms with mark evidence of oxidative injury and bone marrow response consistent with a regenerative normocytic hypochromic anaemia. Except alkaline phosphatase (ALP), all blood chemistry analytes where higher in mainland animals, with particular emphasis on creatine kinase (CK), alanine amino transferase (ALT), aspartate amino transferase (AST) and vitamin E. Some other key findings include a widespread presence of a novel herpesvirus (MaHV-6), the recovery of Cryptococcus neoformans var. -

Egernia Stokesii) National Recovery Plan

Western Spiny-tailed Skink (Egernia stokesii) National Recovery Plan Wildlife Management Program No. 53 Prepared by David Pearson Department of Environment and Conservation WESTERN AUSTRALIAN WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PROGRAM NO. 53 Western Spiny-tailed Skink (Egernia stokesii) Recovery Plan 2012 Department of Environment and Conservation Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 FOREWORD Recovery Plans are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) Policy Statements Nos. 44 and 50 (CALM, 1992; CALM, 1994), and the Australian Government Department for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC) Recovery Planning Compliance Checklist for Legislative and Process Requirements (DEWHA, 2008). Recovery Plans outline the recovery actions that are required to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds necessary to implement actions are subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. This Recovery plan was approved by the Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia. Approved Recovery Plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in status of the taxon or ecological community, and the completion of recovery actions. Information in this Recovery Plan was accurate at June 2012. Recovery Plan Preparation: This recovery plan was prepared by David Pearson (Department of Environment and Conservation, Science Division). Holly Raudino and Manda Page assisted with editing and formatting, and Amy Mutton and Brianna Wingfield prepared the map. Citation: Department of Environment and Conservation (2012). -

Numbat Myrmecobius Fasciatus

Threatened Species Strategy – Year 3 Priority Species Scorecard (2018) Numbat Myrmecobius fasciatus Key Findings Numbats were once widespread across mainland Australia but declined to only ~300 individuals in WA by the late 1970s, primarily due to predation by foxes and habitat loss, as well as predation by feral cats, and frequent and intense fires. Long term control of introduced predators and careful fire management increased populations, enabling translocations to other sites to re-establish Numbats in parts of their former range, firstly in WA and more recently in SA and NSW. These intensive and long-term recovery efforts have increased the total population to over 1300 individuals. Photo: Alexander Dudley Significant trajectory change from 2005-15 to 2015-18? Yes, rate of increase has improved. Priority future actions • Maintain existing fenced populations and develop plan for metapopulation management. • Intensify feral cat control at all established populations (outside of fences). • Establish further populations across range. Full assessment information Background information 2018 population trajectory assessment 1. Conservation status and taxonomy 8. Expert elicitation for population trends 2. Conservation history and prospects 9. Immediate priorities from 2019 3. Past and current trends 10. Contributors 4. Key threats 11. Legislative documents 5. Past and current management 12. References 6. Support from the Australian Government 13. Citation 7. Measuring progress towards conservation The primary purpose of this scorecard is to assess progress against the year three targets outlined in the Australian Government’s Threatened Species Strategy, including estimating the change in population trajectory of 20 mammal species. It has been prepared by experts from the National Environmental Science Program’s Threatened Species Recovery Hub, with input from a number of taxon experts, a range of stakeholders and staff from the Office of the Threatened Species Commissioner, for the information of the Australian Government and is non-statutory. -

Annual Report 2002-2003

CONTENTS NEXT > Zoological Parks Authority ANNUAL REPORT 2002-2003 Mission Statement ZOOLOGICAL PARKS AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT 2002-2003 < BACK CONTENTS NEXT > MISSION STATEMENT To advance the conservation of wildlife and change community attitudes towards the preservation of life on earth. In line with State Government requirements, Perth Zoo’s annual report - the Zoological Parks Authority Annual Report 2002-2003 - is published in an electronic format (replacing the previous printed publications), with limited use of graphics and illustrations to help minimise down load times. Perth Zoo encourages people to use recycled paper if they print a copy of this report or sections of it. For the convenience of readers and to minimise down load times and print outs, the annual report has been presented in sections, as well as the entire document. The annual report is presented in PDF format. All sections, except the financial statements, are also presented in Word format. Anyone requiring the financial statements in a different format, should contact Perth Zoo. Zoological Parks Authority Annual Report 2002-2003 © Zoological Parks Authority 2003 ISSN 1447-6711 (On-line) ISSN 1447-672X (Print) This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes if an acknowledgment of the source is included. Such use must not be for the purpose of sale or commercial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form by any means of any part of the work other than for the purposes above is not permitted without prior written authorisation from the Zoological Parks Authority. -

Yanchep National Park, Western Australia

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2008 A changing cultural landscape: Yanchep National Park, Western Australia Darren P. Venn Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Place and Environment Commons Recommended Citation Venn, D. P. (2008). A changing cultural landscape: Yanchep National Park, Western Australia. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/28 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/28 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Trails, Parks and Picnics Guide(PDF, 6MB)

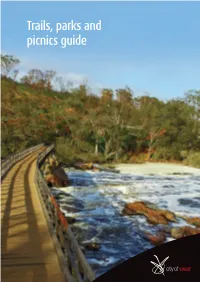

Trails, parks and picnics guide Trails, parks and picnics guide 1 The City of Swan is home to many outdoor parks and attractions. This guide provides an overview of some of the walk trails, parks, picnic areas and playgrounds within the City. Covering the areas of Guildford, Midland, Swan Valley, Ellenbrook, Gidgegannup and Millendon, the guide is a useful tool for exploring and finding walk trails, family friendly cycle routes, great drive trails and a park or playground to have your next picnic. For a full list of parks and recreational areas visit www.swan.wa.gov.au Bookable spaces Some of the public open spaces shown in this brochure require a booking for use. A booking does not guarantee exclusive use, but it will assist in ensuring that there are no double bookings for events such as wedding ceremonies. If you would like to book a space or would like further information, please contact the City of Swan Facilities Booking team on 9267 9321 or by email at [email protected] Use of barbecues Electric barbecues are free to use and can be used at any time throughout the year. From December to March, the use of wood fired barbecues is subject to prevailing fire conditions during the prohibited burning season. If you are unsure of the restrictions that are in place at the time you wish to use a wood fired barbecue, please contact the City’s Community Safety Advocates on 9267 9326. Please note that firewood is not provided for wood fired barbecues. Swan Valley Visitor Centre The Swan Valley Visitor Centre can provide assistance with tours, brochures, accommodation bookings and general information on the Swan Valley, Guildford and surrounding areas.