The Clearances in South-East Sutherland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gunn Herald

THE GUNN HERALD THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE CLAN GUNN SOCIETY Published tri-annually in February, June and October Volume no. 91: October 2013 CONTENTS Office Bearers Inside front cover Contents Page 1 Editorial Page 2 President’s Message Page 3 The First Clan Gunn Magazine Page 4 Commemoration of the Kildonan Clearances Page 5 The Clan Gunn at Ashbourne Page 7 The Canadian Summer Festival Circuit Page 9 Walter Scott & Russia Page 11 What’s in a name? Page 13 Membership Report Page 15 1 EDITORIAL anything, lamented living so far from Afternoon all, London’s flagship Topshop. However, when I was 18 and moved down to Exeter to go to For those of you who don’t know already University I was part of only 7 people whom I will be attempting to fill some very big I ever met there who were Scottish. People boots left by Dave Taylor in the role of looked at me in amazement when I told them Editor of the Herald. For the more regular where I was from, incredulous that anyone attendees of clan events my face may be a would travel so far. Or indeed, disbelieving rather distant memory as it has been a few that anyone who was not a gravy-loving years since my last Clan Gunn Gathering. cretin could exist north of the border. I began Three years at University and a good few to be at first defensive of my heritage and summer jaunts to distant sunspots always then proud, I loved that I was part of such a seemed to coincide with festivities in the minority, that people asked me questions North and it is with regret that I must inform about life in Edinburgh as if I’d just stashed you I am no longer 4ft tall, wear t-shirts my loincloth and crawled out deepest, proclaiming my status as “big sister” and darkest Peru. -

Painting Time: the Highland Journals of John Francis Campbell of Islay

SCOTTISH ARCHIVES 2013 Volume 19 © The Scottish Records Association Painting Time: The Highland Journals of John Francis Campbell of Islay Anne MacLeod This article examines sketches and drawings of the Highlands by John Francis Campbell of Islay (1821–85), who is now largely remembered for his contribution to folklore studies in the north-west of Scotland. An industrious polymath, with interests in archaeology, ethnology and geological science, Campbell was also widely travelled. His travels in Scotland and throughout the world were recorded in a series of journals, meticulously assembled over several decades. Crammed with cuttings, sketches, watercolours and photographs, the visual element within these volumes deserves to be more widely known. Campbell’s drawing skills were frequently deployed as an aide-memoire or functional tool, designed to document his scientific observations. At the same time, we can find within the journals many pioneering and visually appealing depictions of upland and moorland scenery. A tension between documenting and illuminating the hidden beauty of the world lay at the heart of Victorian aesthetics, something the work of this gentleman amateur illustrates to the full. Illustrated travel diaries are one of the hidden treasures of family archives and manuscript collections. They come in many shapes and forms: legible and illegible, threadbare and richly bound, often illustrated with cribbed engravings, hasty sketches or careful watercolours. Some mirror their published cousins in style and layout, and were perhaps intended for the print market; others remain no more than private or family mementoes. This paper will examine the manuscript journals of one Victorian scholar, John Francis Campbell of Islay (1821–85). -

Sutherland Local Plan: Housing Feedback Comments

SUTHERLAND LOCAL PLAN: HOUSING FEEDBACK COMMENTS Housing For example: In light of the likely need for housing in your community are there any particular sites you would like to see developed? Do you have a view on the level of need and type of affordable housing required? Can crofting land contribute to meeting the demand for housing? General • There is plenty of land for development locally if permission was to be GIVEN! • Yes, you need to see to it that land is made available for house building and small farming. The rest would follow by natural investment and economic development. • Much of the new housing is haphazard; spoiling the beautiful rural areas of the country. Unattractive modern boxes. Need for housing for key workers, perhaps subsidised and only allowed to be sold to other key workers, not above the rate of inflation, definitely not to the retired or as second homes. • I cannot understand why permission is granted to build new houses when so many houses ripe for renovation are allowed to deteriorate until they are beyond redemption. • Develop only where there is public waste drainage. It is environmentally unsound to build more and more new houses in crofting areas. Invest in environmentally friendly septic tank solution i.e. enforce the creation of reed beds etc. to clear waste. • New house building to be allowed after planning consent for main house to automatically be allowed to expand for future children i.e. new wing or zone, larger housing in ground. Owners then do not have to have children move away and still allow for offspring independence with open market (see natural and cultural heritage.) • No – business brings work. -

Full Set of Board Papers

Assynt House Beechwood Park Inverness, IV2 3BW Telephone: 01463 717123 Fax: 01463 235189 Textphone users can contact us via Date of Issue: Typetalk: Tel 0800 959598 23 November 2012 www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk HIGHLAND NHS BOARD MEETING OF BOARD Tuesday 4 December 2012 at 8.30 am Board Room, Assynt House, Beechwood Park, Inverness AGENDA 1 Apologies 1.1 Declarations of Interest – Members are asked to consider whether they have an interest to declare in relation to any item on the agenda for this meeting. Any Member making a declaration of interest should indicate whether it is a financial or non-financial interest and include some information on the nature of the interest. Advice may be sought from the Board Secretary’s Office prior to the meeting taking place. 2 Minutes of Meetings of 2 October and 6 November 2012 and Action Plan (attached) (PP 1 – 24) The Board is asked to approve the Minute. 2.1 Matters Arising 3 PART 1 – REPORTS BY GOVERNANCE COMMITTEES 3.1 Argyll & Bute CHP Committee – Draft Minute of Meeting held on 31 October 2012 (attached) (PP 25 – 40) 3.2 Highland Health & Social Care Governance Committee Assurance Report of 1 November 2012 (attached) (PP 41 – 54) 3.3 Highland Health & Social Care Governance Committee – Terms of Reference for approval by the Board (attached) (PP 55 – 58) 3.4 Clinical Governance Committee – Draft Minute of Meeting of 13 November 2012 (attached) (PP 59 – 68) 3.5 Improvement Committee Assurance Report of 5 November 2012 and Balanced Scorecard (attached) (PP 69 – 80) 3.6 Area Clinical Forum – Draft Minute of Meeting held on 27 September 2012 (attached) (PP 81 – 88) 3.7 Asset Management Group – Draft Minutes of Meetings of 18 September and 23 October 2012 (attached) (PP 89 – 96) 3.8 Pharmacy Practices Committee (a) Minute of Meeting of 12 September 2012 – Gaelpharm Limited (attached) (PP 97 – 118) (b) Minute of Meeting of 30 October 2012 – Mitchells Chemist Limited (attached) (PP 119 – 134) The Board is asked to: (a) Note the Minutes. -

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol. 22 : Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies 1 Vol. 22: Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh (East Sutherland & Caithness) Author: Kurt C. Duwe 2nd Edition January, 2012 Executive Summary This publication is part of a series dealing with local communities which were predominantly Gaelic- speaking at the end of the 19 th century. Based mainly (but not exclusively) on local population census information the reports strive to examine the state of the language through the ages from 1881 until to- day. The most relevant information is gathered comprehensively for the smallest geographical unit pos- sible and provided area by area – a very useful reference for people with interest in their own communi- ty. Furthermore the impact of recent developments in education (namely teaching in Gaelic medium and Gaelic as a second language) is analysed for primary school catchments. Gaelic once was the dominant means of conversation in East Sutherland and the western districts of Caithness. Since the end of the 19 th century the language was on a relentless decline caused both by offi- cial ignorance and the low self-confidence of its speakers. A century later Gaelic is only spoken by a very tiny minority of inhabitants, most of them born well before the Second World War. Signs for the future still look not promising. Gaelic is still being sidelined officially in the whole area. Local council- lors even object to bilingual road-signs. Educational provision is either derisory or non-existent. Only constant parental pressure has achieved the introduction of Gaelic medium provision in Thurso and Bonar Bridge. -

Mapping Farmland Wader Distributions and Population Change to Identify Wader Priority Areas for Conservation and Management Action

Mapping farmland wader distributions and population change to identify wader priority areas for conservation and management action Scott Newey1*, Debbie Fielding1, and Mark Wilson2 1. The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, AB15 8QH 2. The British Trust for Ornithology Scotland, Stirling, FK9 4NF * [email protected] Introduction Many birds have declined across Scotland and the UK as a whole (Balmer et al. 2013, Eaton et al. 2015, Foster et al. 2013, Harris et al. 2017). These include five species of farmland wader; oystercatcher, lapwing, curlew, redshank and snipe. All of these have all been listed as either red or amber species on the UK list of birds of conservation concern (Harris et al. 2017, Eaton et al. 2015). Between 1995 and 2016 both lapwing and curlew declined by more than 40% in the UK (Harris et al. 2017). The UK harbours an estimated 19-27% of the curlew’s global breeding population, and the curlew is arguably the most pressing bird conservation challenge in the UK (Brown et al. 2015). However, the causes of wader declines likely include habitat loss, alteration and homogenisation (associated strongly with agricultural intensification), and predation by generalist predators (Brown et al. 2015, van der Wal & Palmer 2008, Ainsworth et al. 2016). There has been a concerted effort to reverse wader declines through habitat management, wader sensitive farming practices and predator control, all of which are likely to benefit waders at the local scale. However, the extent and severity of wader population declines means that large scale, landscape level, collaborative actions are needed if these trends are to be halted or reversed across much of these species’ current (and former) ranges. -

Cormack, Wade

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Sport and Physical Education in the Northern Mainland Burghs of Scotland c. 1600-1800 Cormack, Wade DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2016 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Sport and Physical Education in the Northern Mainland Burghs of Scotland c. -

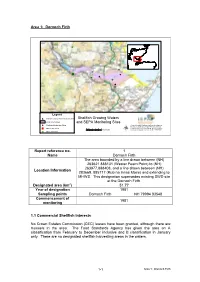

Area 1: Dornoch Firth Shellfish Growing Waters and SEPA Monitoring Sites Report Reference No. 1 Name Dornoch Firth Location

Area 1: Dornoch Firth ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_^_ ! ^_ # ^_ # ^_ ^_ Legend # Shellfish Growing Waters Monitoring Sites Shellfish Growing Waters Shellfish Growing Waters and SEPA Monitoring Sites ! Shellfish Production Sites (c) 2004 Scottish Environment Protection Agency. Includes material based upon Ordnance Survey " Marine Fish Farms 00.51 2 3 4 5 mapping with permission of H.M. Stationery Office. Kilometers (c) Crown Copyright. Licence number 100020538. ^_ Major Discharges µ Report reference no. 1 Name Dornoch Firth The area bounded by a line drawn between (NH) 263621 888131 (Wester Fearn Point) to (NH) 263977,888408, and a line drawn between (NH) Location Information 283669, 885717 (Rub na Innse Moire) and extending to MHWS. This designation supersedes existing SWD site at the Dornoch Firth. Designated area (km2) 51.77 Year of designation 1981 Sampling points Dornoch Firth NH 79994 83548 Commencement of 1981 monitoring 1.1 Commercial Shellfish Interests No Crown Estates Commission (CEC) leases have been granted, although there are mussels in the area. The Food Standards Agency has given the area an A classification from February to December inclusive and B classification in January only. There are no designated shellfish harvesting areas in the waters. 1- 1 Area 1: Dornoch Firth 1.2 Bathymetric Information This shellfish water encompasses almost the entire area of the Dornoch Firth. The area is some 22 km long by a maximum of 5.5 km wide. The maximum charted depth (at LAT) is <10 m. Approximately half of the area is <0 m chart depth, ie intertidal area exposed at low tide. -

Highland Primary Care Nhs Trust

PHARMACY PRACTICES COMMITTEE MEETING Tuesday, 30 October, 2012 at 1.30 pm Seminar Room, Migdale Hospital, Cherry Grove, Bonar Bridge, IV24 3ER Application by Gareth Dixon of MITCHELLS CHEMIST LTD for the provision of general pharmaceutical services at The Former Bonar Bridge News, Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge, IV24 3EB PRESENT Okain Maclennan (Chair) Margaret Thomson (Lay Member) Michael Roberts (Lay member) Susan Taylor (GP Sub Committee Nominate) Fiona Thomson (APC Non Contractor Nominate) John McNulty (APC Contractor Nominate) In Attendance Andrew J Green (Area Regulations, Contracts & Controlled Drugs Governance Pharmacist) Helen M MacDonald (Community Pharmacy Business Manager) Gareth Dixon, Mitchells Chemist Ltd, Applicant Donna Gillespie, Mitchells Chemist Ltd, Applicant Support Christopher Mair, GP Sub Committee Andrew Paterson, Area Pharmaceutical Committee Observers Nicola Macdonald (APC Contractor Nominate NHS Highland PPC Member in training) 1. The Chair welcomed everyone to Bonar Bridge. He asked all members to confirm that they had all received the papers for the hearing and had read and considered them. All members affirmed these points. 2. APPLICATION FOR INCLUSION IN THE BOARD’S PHARMACEUTICAL LIST Case No: PPC – Bonar Bridge, Sutherland. Mitchells Chemist Ltd, The former Bonar Bridge News, Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge, IV24 3EB. The Chair asked each Committee member if there were any interests to declare in relation to the application being heard from Mitchells Chemist Ltd. No interests were declared. 3. The Committee was asked to consider the application submitted by Mitchells Chemist Ltd to provide general pharmaceutical services from premises sited at The former Bonar Bridge News, Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge, IV24 3EB under Regulation 5(10) of the National Health Service (Pharmaceutical Services) (Scotland) Regulations 2009, as amended. -

2014 2 Friendly Companion January 2014

TThhee Friendly Companion Friendly Companion “The L ORD hath made all things for Himself.” (Proverbs 16. 4.) January 2014 2 Friendly Companion January 2014 Editor: Mr. G.D. Buss, “Bethany,” 7 Laines Head, Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN15 1PH. Tel: 01249 656910. Email: [email protected] All correspondence (except that which relates to subscriptions) to be sent to the Editor. Annual Subscriptions inc. postage: U.K. U.S.A. & Canada Australia Europe (Netherlands) £13.50 $36 A$38 €25.00 All correspondence concerning subscriptions should be addressed to Mr. D. Christian, 5, Roundwood Gardens, Harpenden, Herts. AL5 3AJ. Cheques should be made out to Gospel Standard Publications. For United States and Canada, please send to Mr. G. Tenbroeke, 1725 Plainwood Drive, Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081, USA. Volume 140 January 2014 CONTENTS Our Monthly Message 3 Our Front Cover Picture 4 Good Wishes 5 For The Very Little Ones: Naomi Returns 6 Colouring Text: Ruth 1. 22. 7 Bible Lessons: The Burial Of Jesus 8 Three ‘B’s For 2014 10 A Dark Episode 12 Naaman 17 Sin 17 The Necessity Of Divine Life 18 Editor’s Postbag 18 Fascinating Flowerpots 19 Bible Study For The Older Ones: Light And Darkness (I) 20 Bible Questions: Washing And Making Clean 22 Poetry: A Conversation Between Two Brothers 24 Friendly Companion January 2014 3 OUR MONTHLY MESSAGE Dear Children and Young People, As you pick up the Friendly Companion this month it will be to read the first issue of another year. How quickly, to those of us who are older, do the years fly past! When you are younger, often time seems to drag, and there is a danger that you might wish your time away faster than God intends. -

Equality and Communities Division.Dot

Local Government and Communities Directorate Planning and Architecture Division T: 0131-244-0237 E: [email protected] Email to Heads Of Planning ___ 3 March 2020 COMMERCIAL PEAT EXTRACTION SITES IN SCOTLAND You may recall that in my letter of 6 November 2019 I indicated that I would be writing to you again to seek your assistance on improving our understanding around commercial peat extraction in Scotland The Scottish Government recognises the important role peatlands play in responding to the global climate emergency and its ability to lock away carbon. This information request stems from the Scottish Government’s Programme for Government commitment to seek to phase out the use of horticultural peat, and we wish to gain an overall picture of the scale of commercial peat extraction in Scotland at this time. Specifically, we wish to understand the current volume of peat extraction and timescales around when planning permission is due to expire. I appreciate that information pertaining to planning consent for commercial peat extraction is likely to, in certain cases, date back quite some time. Nevertheless, I would be grateful for your support in completing a short survey, as far as possible, for each site within your planning authority. Based on information from BRITPITS, produced by British Geological Survey, we have identified sites across Scotland related to peat extraction along with what we understand to be the current status of those sites. (See Annex A). For those authorities with sites identified in Annex A, I would be grateful if you could complete the survey in Annex B for each relevant site. -

The Records of the County of Sutherland Have Been Arranged and Referenced As Under

COUNTY OF SUTHERLAND The records of the County of Sutherland have been arranged and referenced as under: 1. Commissioners of Supply 1. Minutes 2. Enrolment Committee – Minutes 2. PRE – 1890 Highway Authorities 1. County Road Trustees. Minutes 3. County Council 1. Minutes 2. Committee etc, Minutes - Education 3. “ - Standing Joint 4. “ - Public Health 5. “ - Road board, Bonar Bridge Joint 6. “ - District & Sub-Committees 7. Valuation Rolls 8. Mortgage Registers. 9. Registers of 1. Motor Car Licences 1905-1929 2. Register of Driver Licences 1905-1920 4. County Treasurer’s Department 1. Abstracts of Accounts 5. Education 1. County Secondary Education Committee – Minutes 2. Education Authority Minutes 3. School Board Records 4. School Management and Education District Sub-Committee – Minutes 5. School Log Books and Admission Registers 6. Unallocated 7. Unallocated 6. Parish Records 7. Miscellanea 8. Unallocated 9. Unallocated 10. Unallocated 11. Unallocated 12. Assessors Office 1. Electoral Registers COUNTY OF SUTHERLAND County of Sutherland Public Assistance Office/Social Work Department Records, c1925-1974. The records were located in a redundant building, ‘Woodlands’, in Dornoch, previously used as the Social Work Area Office for Sutherland. The records were deposited by the Director of Social Work in March 1992. Index. A.1 Correspondence files 1930-1963 B. 1-6 Subject files 1932-1974 C. 1-5 Statistics, 1934-1974 D. 1-15 Registers 1925-c1948 E. 1-2 Financial records, 1949-1970 F. 1-5 Papers of Sutherland Probation Committee, 1933 – 1968 G. 1-12 Emergency Relief records, 1940-1950 H. 1 Salaries records, 1946-1948 I. 1-9 Miscellaneous records 1.