Thesis&Preparation&Appr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Savannah Scottish Games & Highland Gathering

47th ANNUAL CHARLESTON SCOTTISH GAMES-USSE-0424 November 2, 2019 Boone Hall Plantation, Mount Pleasant, SC Judge: Fiona Connell Piper: Josh Adams 1. Highland Dance Competition will conform to SOBHD standards. The adjudicator’s decision is final. 2. Pre-Premier will be divided according to entries received. Medals and trophies will be awarded. Medals only in Primary. 3. Premier age groups will be divided according to entries received. Cash prizes will be awarded as follows: Group 1 Awards 1st $25.00, 2nd $15.00, 3rd $10.00, 4th $5.00 Group 2 Awards 1st $30.00, 2nd $20.00, 3rd $15.00, 4th $8.00 Group 3 Awards 1st $50.00, 2nd $40.00, 3rd $30.00, 4th $15.00 4. Trophies will be awarded in each group. Most Promising Beginner and Most Promising Novice 5. Dancer of the Day: 4 step Fling will be danced by Premier dancer who placed 1st in any dance. Primary, Beginner and Novice Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 9:00 AM- Competition to begin at 9:30 AM Beginner Steps Novice Steps Primary Steps 1. Highland Fling 4 5. Highland Fling 4 9. 16 Pas de Basque 2. Sword Dance 2&1 6. Sword Dance 2&1 10. 6 Pas de Basque & 4 High Cuts 3. Seann Triubhas 3&1 7. Seann Triubhas 3&1 11. Highland Fling 4 4. 1/2 Tulloch 8. 1/2 Tulloch 12. Sword Dance 2&1 Intermediate and Premier Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 12:30 PM- Competition to begin at 1:00 PM Intermediate Premier 15 Jig 3&1 20 Hornpipe 4 16 Hornpipe 4 21 Jig 3&1 17 Highland Fling 4 22. -

The Celtic Revival in English Literature, 1760-1800

ZOh. jU\j THE CELTIC REVIVAL IN ENGLISH LITERATURE LONDON : HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The "Bard The Celtic Revival in English Literature 1760 — 1800 BY EDWARD D. SNYDER B.A. (Yale), Ph.D. (Harvard) CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1923 COPYRIGHT, 1923 BY HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINTED AT THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS CAMBRIDGE, MASS., U. S. A. PREFACE The wholesome tendency of modern scholarship to stop attempting a definition of romanticism and to turn instead to an intimate study of the pre-roman- tic poets, has led me to publish this volume, on which I have been intermittently engaged for several years. In selecting the approximate dates 1760 and 1800 for the limits, I have been more arbitrary in the later than in the earlier. The year 1760 has been selected because it marks, roughly speaking, the beginning of the Celtic Revival; whereas 1800, the end of the century, is little more than a con- venient place for breaking off a history that might have been continued, and may yet be continued, down to the present day. Even as the volume has been going through the press, I have found many new items from various obscure sources, and I am more than ever impressed with the fact that a collection of this sort can never be complete. I have made an effort, nevertheless, to show in detail what has been hastily sketched in countless histories of literature — the nature and extent of the Celtic Revival in the late eighteenth century. Most of the material here presented is now pub- lished for the first time. -

Swedish Folk Music

Ronström Owe 1998: Swedish folk music. Unpublished. Swedish folk music Originally written for Encyclopaedia of world music. By Owe Ronström 1. Concepts, terminology. In Sweden, the term " folkmusik " (folk music) usually refers to orally transmitted music of the rural classes in "the old peasant society", as the Swedish expression goes. " Populärmusik " ("popular music") usually refers to "modern" music created foremost for a city audience. As a result of the interchange between these two emerged what may be defined as a "city folklore", which around 1920 was coined "gammeldans " ("old time dance music"). During the last few decades the term " folklig musik " ("folkish music") has become used as an umbrella term for folk music, gammeldans and some other forms of popular music. In the 1990s "ethnic music", and "world music" have been introduced, most often for modernised forms of non-Swedish folk and popular music. 2. Construction of a national Swedish folk music. Swedish folk music is a composite of a large number of heterogeneous styles and genres, accumulated throughout the centuries. In retrospect, however, these diverse traditions, genres, forms and styles, may seem as a more or less homogenous mass, especially in comparison to today's musical diversity. But to a large extent this homogeneity is a result of powerful ideological filtering processes, by which the heterogeneity of the musical traditions of the rural classes has become seriously reduced. The homogenising of Swedish folk music started already in the late 1800th century, with the introduction of national-romantic ideas from German and French intellectuals, such as the notion of a "folk", with a specifically Swedish cultural tradition. -

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

René Galand, the Emsav in a Novel of Yeun Ar Gow

René Galand, The Emsav in a novel of Yeun ar Gow Brittany’s struggle to regain its liberties (the Emsav , in Breton), is a major theme in XXth century Breton literature, as I have had occasion to show in other publications.1 The links between the Emsav and literature can be quite complex: this has been clearly demonstrated notably by Pierrette Kermoal in her study of two works of Roparz Hemon, the poem Gwarizi vras Emer [Emer’s great jealousy] and the novel Mari Vorgan .2 She shows how the Breton nationalist ideal is manifested in the form of two beautiful women whose essence is supernatural, the fairy Fant in the poem, and the mermaid Levenez in dthe novel. P. Kermoal does not mention Donalda Kerlaban, the protagonist of Hemon’s utopian novel An Aotrou Bimbochet e Breizh , but she clearly is another manifestation of the author’s ideal, an incarnation of his country’s revival. Roparz Hemon makes use of the image of a supernatural woman (or of a woman situated outside of time) like the ancient Irish poets who used her as a symbol of Irish sovereignty. 3 In fact, what the critic Youenn Olier wrote about Roparz Hemon might well be applied to many other Breton writers, à l’instar des anciens poètes irlandais qui symbolisaient ainsi la royauté de leur pays. 4 A vrai dire, on pourrait appliquer à bon nombre d’écrivains bretons ce qu’écrivait Youenn Olier à propos de Roparz Hemon :"... e oberenn lennegel a zo bet heklev an Emsav dre vras" [His literary work has largely been an echo of the Emsav ]. -

Manx Gaelic and Physics, a Personal Journey, by Brian Stowell

keynote address Editors’ note: This is the text of a keynote address delivered at the 2011 NAACLT conference held in Douglas on The Isle of Man. Manx Gaelic and physics, a personal journey Brian Stowell. Doolish, Mee Boaldyn 2011 At the age of sixteen at the beginning of 1953, I became very much aware of the Manx language, Manx Gaelic, and the desperate situation it was in then. I was born of Manx parents and brought up in Douglas in the Isle of Man, but, like most other Manx people then, I was only dimly aware that we had our own language. All that changed when, on New Year’s Day 1953, I picked up a Manx newspaper that was in the house and read an article about Douglas Fargher. He was expressing a passionate view that the Manx language had to be saved – he couldn’t understand how Manx people were so dismissive of their own language and ignorant about it. This article had a dra- matic effect on me – I can say it changed my life. I knew straight off somehow that I had to learn Manx. In 1953, I was a pupil at Douglas High School for Boys, with just over two years to go before I possibly left school and went to England to go to uni- versity. There was no university in the Isle of Man - there still isn’t, although things are progressing in that direction now. Amazingly, up until 1992, there 111 JCLL 2010/2011 Stowell was no formal, official teaching of Manx in schools in the Isle of Man. -

Celtic-International-Fund-2019.Pdf

CELTIC INTERNATIONAL FUND BBC ALBA (with funding from MG ALBA), S4C, TG4 and Northern Ireland Screen’s Irish Language Broadcast Fund (ILBF) are delighted to announce the second round of the ‘Celtic International Fund’, a yearly joint-commissioning round between the indigenous Celtic language television broadcasters and funders of Scotland, Wales, Ireland and Northern Ireland The aim of the ‘Celtic International Fund’ is to promote co-development and then co-production through Scottish Gaelic, Welsh and Irish, and to encourage a broader European and worldwide internationalisation of productions which are originally conceived in those Celtic languages. The Celtic International Fund hopes to provide film-makers with an opportunity to co-develop and coproduce distinctive, ambitious works to enrich primetime programme schedules, to have a national impact with audiences in the territories of Scotland, Wales, Ireland and Northern Ireland and seek to reach audiences worldwide. This call-out encompasses three genres, Factual, Formats and Drama. For all projects, we envisage a development phase where funding would be provided to develop ideas but also to develop the co- production framework which must have a production element in Scotland, Wales and either Ireland or Northern Ireland. Feedback from producers regarding genres to be included in ensuing Celtic International Fund call-outs is welcome. The Celtic International Fund will be administered by a joint commissioning team drawn from the Celtic language broadcasters and funders who are partners -

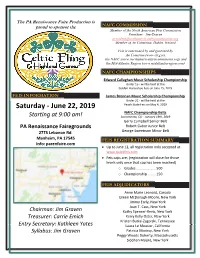

June 22, 2019

The PA Renaissance Faire Production is proud to sponsor the NAFC COMMISSION Member of the North American Feis Commission President: Jim Graven [email protected] Member of An Coimisiun, Dublin, Ireland Feis is sanctioned by and governed by An Comisiun (www.clrg.ie), the NAFC (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) and the Mid-Atlantic Region (www.midatlanticregion.com) NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS Edward Callaghan Music Scholarship Championship Under 15 - will be held at the Golden Horseshoe Feis on June 15, 2019 FEIS INFORMATION James Brennan Music Scholarship Championship Under 21 - will be held at the Peach State Feis on May 4, 2019 Saturday - June 22, 2019 NAFC Championship Belts Starting at 9:00 am! Sacramento, CA - January 19th, 2019 Gerry Campbell Senior Belt PA Renaissance Fairegrounds Robert Gabor Junior Belt 2775 Lebanon Rd. George Sweetnam Minor Belt Manheim, PA 17545 FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY Info: parenfaire.com Up to June 12, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades ..................... 500 o Championship ......... 150 FEIS ADJUDICATORS Anne Marie Leonard, Canada Eileen McDonagh-Moore, New York Jimmy Early, New York Joan T. Cass, New York Chairman: Jim Graven Kathy Spencer-Revis, New York Treasurer: Carrie Emich Kerry Kelly Oster, New York Kristen Butke-Zagorski, Tennessee Entry Secretary: Kathleen Yates Laura Le Meusier, California Syllabus: Jim Graven Patricia Morissy, New York Peggy Woods Doherty, Massachusetts Siobhan Moore, New York COMPETITION FEES CELTIC FLING FEIS FESTIVAL Feis Admission includes ONE day ticket to the festival Competition Fees FEES (you can purchase a second day ticket at registration) Solo Dancing / TR / Sets / Non-Dance Kick-off concert on Friday featuring great performers! $ 10 Bring your appetite and enjoy delicious foods and (per competitor and per dance) refreshing wines, ales & ciders while listening to the live Preliminary Championship music! Gates open at 4PM. -

The Caledonii Grande Tradition Greetings from the Editorial Staff

amildanachamildanach Journal of Celtic Studies ◊ Caledonii Grande Tradition SS http://www.angelfire.com/sc/Caledonii/ Premiere Edition ◊ Five dollars Greetings from the Editorial Staff It has been several years since the We are striving to present articles Sabbats, Gods and Goddesses of publication of the original Samildanach of worth to those of you who wish the Celts and customs relating to was released. Now, with new to be enriched in your study of them. We invite you to submit your computers and a full Staff comprised Celtic life ways. We’ll also carry articles to our Editorial Staff at least of hard working Caledonii members, sections announcing upcoming six weeks before the release date we hope to bring you this magazine Gatherings around the South East, for each issue. Issues of the zine will of Celtic Studies. You’ll find a lot in and notable Gathers throughout number four a year to correspond this issue which we hope will be of the States; as well as, articles on the to the great Fire Festivals. interest to you. – Continued on page 2 The Caledonii Grande Tradition A Little Background Grande Tradition known as the Wiccans and Mystic Christians can Fellowship of Caledon. In its come together and affirm their By Lord Ariel Morgan meetings, the Druidh, the Elders interconnectedness as Creators Ard Druidh Chosen Chief of the Order and Third Degree, and the Episcopacy, children and as brothers and sisters Wisdom Keeper of the Tradition sit together and create the policies of the Caledonii family. Within the which govern the Caledonii. -

Celts and Celtic Languages

U.S. Branch of the International Comittee for the Defense of the Breton Language CELTS AND CELTIC LANGUAGES www.breizh.net/icdbl.htm A Clarification of Names SCOTLAND IRELAND "'Great Britain' is a geographic term describing the main island GAIDHLIG (Scottish Gaelic) GAEILGE (Irish Gaelic) of the British Isles which comprises England, Scotland and Wales (so called to distinguish it from "Little Britain" or Brittany). The 1991 census indicated that there were about 79,000 Republic of Ireland (26 counties) By the Act of Union, 1801, Great Britain and Ireland formed a speakers of Gaelic in Scotland. Gaelic speakers are found in legislative union as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and all parts of the country but the main concentrations are in the The 1991 census showed that 1,095,830 people, or 32.5% of the population can Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom does not include the Western Isles, Skye and Lochalsh, Lochabar, Sutherland, speak Irish with varying degrees of ability. These figures are of a self-report nature. Channel Islands, or the Isle of Man, which are direct Argyll and Bute, Ross and Cromarly, and Inverness. There There are no reliable figures for the number of people who speak Irish as their dependencies of the Crown with their own legislative and are also speakers in the cities of Edinburgh, Glasgow and everyday home language, but it is estimated that 4 to 5% use the language taxation systems." (from the Statesman's handbook, 1984-85) Aberdeen. regularly. The Irish-speaking heartland areas (the Gaeltacht) are widely dispersed along the western seaboards and are not densely populated. -

E.E. Fournier D'albe's Fin De Siècle: Science, Nationalism and Monistic

Ian B. Stewart E.E. Fournier d’Albe’s Fin de siècle: Science, nationalism and monistic philosophy in Britain and Ireland Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Stewart, Ian B. (2017). E.E. Fournier d’Albe’s Fin de siècle: Science, nationalism and monistic philosophy in Britain and Ireland Cultural and Social History. pp 1-22. ISSN 1478-0038 DOI: 10.1080/14780038.2017.1375721 © 2017 Taylor & Francis This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/84274/ Available in LSE Research Online: September 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. 1 E.E. Fournier d’Albe’s Fin de siècle: Science, Nationalism and Monistic Philosophy in Britain and Ireland* Ian B. Stewart The aim of this article is to reconstruct the intellectual biography of the English physicist Edmund Edward Fournier d’Albe (1868-1933) in order to shed new light on disparate aspects of the British fin de siècle.