Non-Indigenous Rubiaceae Grown in Thailand INTRODUCTION The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montgomery County Landscape Plant List

9020 Airport Road Conroe, TX 77303 (936) 539-7824 MONTGOMERY COUNTY LANDSCAPE PLANT LIST Scientific Name Common Name Size Habit Light Water Native Wildlife Comments PERENNIALS Abelmoschus ‘Oriental Red’ Hibiscus, Oriental Red 3 x 3 D F L N Root hardy, reseeds Abutilon sp. Flowering Maple Var D F M N Acalypha pendula Firetail Chenille 8" x 8" E P H N Acanthus mollis Bear's Breeches 3 x 3 D S M N Root hardy Acorus gramineus Sweet Flag 1 x 1 E P M N Achillea millefolium var. rosea Yarrow, Pink 2 x 2 E F/P M N BF Butterfly nectar plant Adiantum capillus-veneris Fern, Maidenhair 1 x 1 E P/S H Y Dormant when dry Adiantum hispidulum Fern, Rosy Maidenhair 1 x 1 D S H N Agapanthus africanus Lily of the Nile 2 x 2 E P M N Agastache ‘Black Adder’ Agastache, Black Adder 2 x 2 D F M N BF, HB Butterfly/hummingbird nectar plant Ageratina havanensis Mistflower, Fragrant 3 x 3 D F/P L Y BF Can take poor drainage Ageratina wrightii Mistflower, White 2 x 2 D F/P L Y BF Butterfly nectar plant Ajuga reptans Bugle Flower 6" x 6" E P/S M N Alocasia sp. Taro Var D P M N Aggressive in wet areas Aloysia virgata Almond Verbena 8 x 5 D S L N BF Very fragrant, nectar plant Alpinia sp. Gingers, Shell 6 x 6 E F/P M N Amsonia tabernaemontana Texas Blue Star 3 x 3 D P M Y Can take poor drainage Andropogon gerardii Bluestem, Big 3 to 8 D F/P L Y Andropogon glomeratus Bluestem, Brushy 2 to 5 D F/P L Y Andropogon ternarius Bluestem, Splitbeard 1 to 4 D F/P L Y Anisacanthus wrightii Flame Acanthus 3 x 3 D F L Y HB Hummingbird nectar plant Aquilegia chrysantha Columbine, Yellow 2 x 1 E P/S M Y Dormant when dry, reseeds Aquilegia canadensis Columbine, Red 1 x 1 E P/S M Y Dormant when dry, reseeds Ardisia crenata Ardisia 1 x 1 E P/S M N Ardisia japonica Ardisia 2 x 2 E P/S M N Artemisia sp. -

TAXON:Warszewiczia Coccinea

TAXON: Warszewiczia coccinea SCORE: -7.0 RATING: Low Risk (Vahl) Klotzsch Taxon: Warszewiczia coccinea (Vahl) Klotzsch Family: Rubiaceae Common Name(s): chaconier Synonym(s): Macrocnemum coccineum Vahl Trinidad-pride wild poinsettia Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 21 May 2020 WRA Score: -7.0 Designation: L Rating: Low Risk Keywords: Tropical Tree, Ornamental, Butterfly-Pollinated, Self-Incompatible, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 n 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) -

Mussaendas for South Florida Landscapes

MUSSAENDAS FOR SOUTH FLORIDA LANDSCAPES John McLaughlin* and Joe Garofalo* Mussaendas are increasingly popular for the surrounding calyx has five lobes, with one lobe showy color they provide during much of the year conspicuously enlarged, leaf-like and usually in South Florida landscapes. They are members brightly colored. In some descriptions this of the Rubiaceae (madder or coffee family) and enlarged sepal is termed a calycophyll. In many are native to the Old World tropics, from West of the cultivars all five sepals are enlarged, and Africa through the Indian sub-continent, range in color from white to various shades of Southeast Asia and into southern China. There pink to carmine red. are more than 200 known species, of which about ten are found in cultivation, with three of these There are a few other related plants in the being widely used for landscaping. Rubiaceae that also possess single, enlarged, brightly colored sepals. These include the so- called wild poinsettia, Warszewiczia coccinea, DESCRIPTION. national flower of Trinidad; and Pogonopus The mussaendas used in landscapes are open, speciosus (Chorcha de gallo)(see Figure 1). somewhat scrambling shrubs, and range from 2-3 These are both from the New World tropics and ft to 10-15 ft in height, depending upon the both are used as ornamentals, though far less species. In the wild, some can climb 30 ft into frequently than the mussaendas. surrounding trees, though in cultivation they rarely reach that size. The fruit is a small (to 3/4”), fleshy, somewhat elongated berry containing many seeds. These Leaves are opposite, bright to dark green, and are rarely seen under South Florida conditions. -

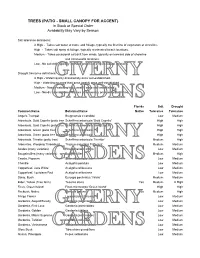

TREES (PATIO - SMALL CANOPY for ACCENT) in Stock Or Special Order Availability May Vary by Season

TREES (PATIO - SMALL CANOPY FOR ACCENT) In Stock or Special Order Availability May Vary by Season Salt tolerance definitions: X High - Takes salt water at roots and foliage, typically the first line of vegetation at shoreline. High - Takes salt spray at foliage, typically at elevated beach locations. Medium - Takes occasional salt drift from winds, typically on leeward side of shoreline and intracoastal locations. Low - No salt drift, typically inland or protected area of coastal locations. Drought tolerance definitions: X High - Watering only occasionally once well-established. High - Watering no more than once weekly once well-established. Medium - Needs watering twice weekly once well-established. Low - Needs watering three or more times weekly once well-established. Florida Salt Drought Common Name Botanical Name Native Tolerance Tolerance Angel's Trumpet Brugmansia x candida Low Medium Arboricola, Gold Capella (patio tree) Schefflera arboricola 'Gold Capella' High High Arboricola, Gold Capella (patio tree braided)Schefflera arboricola 'Gold Capella' High High Arboricola, Green (patio tree) Schefflera arboricola High High Arboricola, Green (patio tree braided)Schefflera arboricola High High Arboricola, Trinette (patio tree) Schefflera arboricola 'Trinette' Medium High Arborvitae, Weeping Threadleaf Thuja occidentalis 'Filiformis' Medium Medium Azalea (many varieties) Rhododrendon indica Low Medium Bougainvillea {many varieties) Bougainvillea x Medium High Cassia, Popcorn Senna didymobotrya Low Medium Chenille Acalypha pendula Low -

Responses of Ornamental Mussaenda Species Stem Cuttings to Varying Concentrations of Naphthalene Acetic Acid Phytohormone Application

GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2017, 01(01), 020–024 Available online at GSC Online Press Directory GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences e-ISSN: 2581-3250, CODEN (USA): GBPSC2 Journal homepage: https://www.gsconlinepress.com/journals/gscbps (RESEARCH ARTICLE) Responses of ornamental Mussaenda species stem cuttings to varying concentrations of naphthalene acetic acid phytohormone application Ogbu Justin U. 1*, Okocha Otah I. 2 and Oyeleye David A. 3 1 Department of Horticulture and Landscape technology, Federal College of Agriculture (FCA), Ishiagu 491105 Nigeria. 2 Department of Horticulture technology, AkanuIbiam Federal Polytechnic, Unwana Ebonyi state Nigeria. 3 Department of Agricultural technology, Federal College of Agriculture (FCA), Ishiagu 491105 Nigeria Publication history: Received on 28 August 2017; revised on 03 October 2017; accepted on 09 October 2017 https://doi.org/10.30574/gscbps.2017.1.1.0009 Abstract This study evaluated the rooting and sprouting responses of four ornamental Mussaendas species (Flag bush) stem cuttings to treatment with varying concentrations of 1-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA). Species evaluated include Mussaenda afzelii (wild), M. erythrophylla, M. philippica and Pseudomussaenda flava. Different concentrations of NAA phytohormone were applied to the cuttings grown in mixed river sand and saw dust (1:1; v/v); and laid out in a 4 x 4 factorial experiment in completely randomized design (CRD; r=4). Results showed that increasing concentrations of NAA application slowed down emerging shoot bud in M. afzelii, P. flava, M. erythrophylla and M. philippica. While other species responded positively at some point to increased concentrations of the NAA applications, the P. flava showed retarding effect of phytohormone treatment on its number of leaves. -

Red Plants for Hawai'i Landscapes

Ornamentals and Flowers Jan. 2010 OF-49 Red Plants for Hawai‘i Landscapes Melvin Wong Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences his publication focuses on plants The plants with red coloration having red as their key color. In shown here are just a few of the pos- theT color wheel (see Wong 2006), sibilities. Their selection is based red is opposite to (and therefore the on my personal aesthetic preference “complement” of) green, which is the and is intended to give you a start in dominant color in landscapes because developing your own list of plants to it is the color of most foliage. The provide red highlights to a landscape. plants selected for illustration here Before I introduce a new plant can create exciting variation when species into my garden or landscape, I juxtaposed with green in landscapes want to know that it is not invasive in of tropical and subtropical regions. Hawai‘i. Some plants have the ability Lots of red can be used in landscapes to escape from their original plant- because equal amounts of red will bal- ing area and spread into disturbed or ance equal amounts of green. natural areas. Invasive plant species Many plants that can exist in a can establish populations that survive tropical or subtropical environment without human help and can expand do not necessarily give the feeling of a into nearby and in some cases even “tropical” theme. Examples, in my opinion, are plumerias, distant areas. These plants can outcompete native and bougainvilleas, rainbow shower trees, ixoras, and hibiscuses. agricultural species, causing negative impacts. -

Ornamental Garden Plants of the Guianas Pt. 2

Surinam (Pulle, 1906). 8. Gliricidia Kunth & Endlicher Unarmed, deciduous trees and shrubs. Leaves alternate, petiolate, odd-pinnate, 1- pinnate. Inflorescence an axillary, many-flowered raceme. Flowers papilionaceous; sepals united in a cupuliform, weakly 5-toothed tube; standard petal reflexed; keel incurved, the petals united. Stamens 10; 9 united by the filaments in a tube, 1 free. Fruit dehiscent, flat, narrow; seeds numerous. 1. Gliricidia sepium (Jacquin) Kunth ex Grisebach, Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Gottingen 7: 52 (1857). MADRE DE CACAO (Surinam); ACACIA DES ANTILLES (French Guiana). Tree to 9 m; branches hairy when young; poisonous. Leaves with 4-8 pairs of leaflets; leaflets elliptical, acuminate, often dark-spotted or -blotched beneath, to 7 x 3 (-4) cm. Inflorescence to 15 cm. Petals pale purplish-pink, c.1.2 cm; standard petal marked with yellow from middle to base. Fruit narrowly oblong, somewhat woody, to 15 x 1.2 cm; seeds up to 11 per fruit. Range: Mexico to South America. Grown as an ornamental in the Botanic Gardens, Georgetown, Guyana (Index Seminum, 1982) and in French Guiana (de Granville, 1985). Grown as a shade tree in Surinam (Ostendorf, 1962). In tropical America this species is often interplanted with coffee and cacao trees to shade them; it is recommended for intensified utilization as a fuelwood for the humid tropics (National Academy of Sciences, 1980; Little, 1983). 9. Pterocarpus Jacquin Unarmed, nearly evergreen trees, sometimes lianas. Leaves alternate, petiolate, odd- pinnate, 1-pinnate; leaflets alternate. Inflorescence an axillary or terminal panicle or raceme. Flowers papilionaceous; sepals united in an unequally 5-toothed tube; standard and wing petals crisped (wavy); keel petals free or nearly so. -

Fl. China 19: 231–242. 2011. 56. MUSSAENDA Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1

Fl. China 19: 231–242. 2011. 56. MUSSAENDA Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 177. 1753. 玉叶金花属 yu ye jin hua shu Chen Tao (陈涛); Charlotte M. Taylor Belilla Adanson. Trees, shrubs, or clambering or twining lianas, rarely dioecious, unarmed. Raphides absent. Leaves opposite or occasionally in whorls of 3, with or usually without domatia; stipules persistent or caducous, interpetiolar, entire or 2-lobed. Inflorescences terminal and sometimes also in axils of uppermost leaves, cymose, paniculate, or thyrsiform, several to many flowered, sessile to pedunculate, bracteate. Flowers sessile to pedicellate, bisexual and usually distylous or rarely unisexual. Calyx limb 5-lobed nearly to base, fre- quently some or all flowers of an inflorescence with 1(–5) white to colored, petaloid, persistent or deciduous, membranous, stipitate calycophyll(s) with 3–7 longitudinal veins. Corolla yellow, red, orange, white, or rarely blue (Mussaenda multinervis), salverform with tube usually slender then abruptly inflated around anthers, or rarely constricted at throat (M. hirsuta), inside variously pubescent but usually densely yellow clavate villous in throat; lobes 5, valvate-reduplicate in bud, often long acuminate. Stamens 5, inserted in middle to upper part of corolla tube, included; filaments short or reduced; anthers basifixed. Ovary 2-celled, ovules numerous in each cell, inserted on oblong, fleshy, peltate, axile placentas; stigmas 2-lobed, lobes linear, included or exserted. Fruit purple to black, baccate or perhaps rarely capsular (M. decipiens), fleshy, globose to ellipsoid, often conspicuously lenticellate, with calyx limb per- sistent or caducous often leaving a conspicuous scar; seeds numerous, small, angled to flattened; testa foveolate-striate; endosperm abundant, fleshy. -

To Download the 2020 PDF Version of Mulberry

Mulberry Miniatures 2020-2021 Reference Book featuring “Harmony Plant Collections” by color 1. Fax or call one of the following fine brokers for availability & ordering: BFG PLANT CONNECTION GRIMES HORTICULTURE 14500 Kinsman Rd. P.O. Box 479 11335 Concord-Hambden Rd. Burton, OH 44021 Concord, OH 44077 Phone: (800) 883-0234 Fax:(800) 368-4759 Phone: (800) 241-7333 Fax: (440) 352-1800 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] web: www.bfgsupply.com/order-now/139/plants web: www.grimes-hort.com EASON HORTICULTURAL RESOURCES, INC. McHUTCHISON HORTICULTURAL DIST. 939 Helen Ruth Drive 64 Mountain View Blvd. Ft. Wright, KY 41017 Wayne, NJ 07470 Phone: (800) 214-2221 Fax: (859) 578-2266 Phone: (800) 943-2230 Fax: (866) 234-8884 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] web: www.ehrnet.com web: www.mchutchison.com FRED C. GLOECKNER COMPANY VAUGHAN’S HORTICULTURE 550 Mamaroneck Avenue Suite 510 40 Shuman Blvd., Suite 175 Harrison, NY 10528-1631 Naperville, IL 60563 Phone: (800) 345-3787 Fax: (914) 698-0848 Phone: (855) 864-3300 Fax: (855) 864-5790 email: [email protected] email - [email protected] web: www.fredgloeckner.com web address: www.vaughans.com 2. Consult availability & recent catalog to order by mixed or straight flats: Specs and minimums: - Each tray = 32 plants (4 different varieties x 8 each OR straight 32 plants) - 4 tray minimum (128 plants) - 2 trays per box - After minimum, order in multiples of 2 trays - Shipping charges - Within Ohio: $22. per box - Outside Ohio: $28. per box If you are located within driving distance - Place the order with the broker - Arrange with them to pickup the order at: Perfection Greenhouse LLC 8575 S. -

Cinchona Amazonica Standl. (Rubiaceae) No Estado Do Acre, Brasil1 Cinchona Amazonica Standl

Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Naturais, Belém, v. 1, n. 1, p. 9-18, jan-abr. 2006 Cinchona amazonica Standl. (Rubiaceae) no estado do Acre, Brasil1 Cinchona amazonica Standl. (Rubiaceae) in the state of Acre, Brazil Percy Amilcar Zevallos Pollito I Mário Tomazello Filho II ResumoResumo: O presente estudo trata da dendrologia, distribuição geográfica e status de conservação de Cinchona amazonica Standl., plantas de interesse medicinal que ocorrem no estado do Acre, Brasil. A pesquisa consistiu em trabalhos de campo para a coleta de material botânico, levantamento e estudo das exsicatas disponíveis nos herbários nacionais e internacionais da América do Sul, revisão bibliográfica das espécies do gênero na literatura e nos sites especializados. Os resultados apresentam a descrição com a sua ilustração e mapeamento bem como determinação da sua situação populacional. Palavras-chavealavras-chave: Cinchona. Dendrologia. Ditribuição geográfica. Status de conservação. Acre. AbstractAbstract: The present research is about dendrology, geographic distribution and status of conservation of Cinchona amazonica Standl. with are plants with medical interest; they grow in the state of Acre, Brazil. The research consisted in: field work for the collection of botanical material, in the survey and study of the available exsiccates in the national and international herbariums of the South America. It has been done a bibliographical review of the species of this genera in literature and the specialized sites The results present the description of the species with their illustration and mapping, as well as determination of their population situation. Keywordseywords: Cinchona. Dendrology. Geographic distribution. Conservation status. Acre I Universidade Nacional Agraria La Molina. Faculdad de Ciencias Florestales. -

The Double Chaconia

[email protected] Tel: (868) 667-4655 May 2018 Our National Flower: The Double Chaconia By Professor Julian Duncan & Cheesman, 1928) With regard to the last for propagation. Initially he was named, recorded legend has it that the unsuccessful in getting them rooted; In 1844, Jozef Warszewicz – a Polish red transformed sepals reminded the early a measure of success came with botanist – was sent to Guatemala to French settlers of the chaconne, a peasant assistance from Mr. Roy Nichols join a Belgian company. He became dance popular in 18th century France and of the Imperial College of Tropical an independent collector and supplier Spain in which the dancer decorated their Agriculature (ICTA) and two plants of plants to orists and gardens in shirts with swatches of red ribbon (Adams were sent to Kew in Britain where Europe. He travelled extensively in 1976). they were recognised as a mutant Guatemala, Panama and Costa Rica form of W. coccinea. The plant was where he discovered a wealth of It was chosen as the National ower when assigned the name W.coccinea cv new plant species. Among these was the country became an independent nation ‘David Auyong’ (Nichols, 1963). The Warszewiczia coccinea (Vahl.) Klotzsch. from Britain in 1962. Considering the local name – Pride of Trinidad – a better choice principal di erence between the wild could not have been made. type and the mutant is that in the latter, every ower in a cyme has all The plant produces a compound its sepals transformed to a greater or in orescence, consisting of an axis along lesser extent; this masks the presence which are paired stalked cymes, each of of the petals and accounts for the which contains 15-20 owers. -

Plants and Parts of Plants Used in Food Supplements: an Approach to Their

370 ANN IST SUPER SANITÀ 2010 | VOL. 46, NO. 4: 370-388 DOI: 10.4415/ANN_10_04_05 ES I Plants and parts of plants used OLOG D in food supplements: an approach ETHO to their safety assessment M (a) (b) (b) (b) D Brunella Carratù , Elena Federici , Francesca R. Gallo , Andrea Geraci , N (a) (b) (b) (a) A Marco Guidotti , Giuseppina Multari , Giovanna Palazzino and Elisabetta Sanzini (a)Dipartimento di Sanità Pubblica Veterinaria e Sicurezza Alimentare; RCH (b) A Dipartimento del Farmaco, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy ESE R Summary. In Italy most herbal products are sold as food supplements and are subject only to food law. A list of about 1200 plants authorised for use in food supplements has been compiled by the Italian Ministry of Health. In order to review and possibly improve the Ministry’s list an ad hoc working group of Istituto Superiore di Sanità was requested to provide a technical and scientific opinion on plant safety. The listed plants were evaluated on the basis of their use in food, therapeu- tic activity, human toxicity and in no-alimentary fields. Toxicity was also assessed and plant limita- tions to use in food supplements were defined. Key words: food supplements, botanicals, herbal products, safety assessment. Riassunto (Piante o parti di piante usate negli integratori alimentari: un approccio per la valutazione della loro sicurezza d’uso). In Italia i prodotti a base di piante utilizzati a scopo salutistico sono in- tegratori alimentari e pertanto devono essere commercializzati secondo le normative degli alimenti. Le piante che possono essere impiegate sono raccolte in una “lista di piante ammesse” stabilita dal Ministero della Salute.