Title Suitcase Aesthetics: the Making of Memory in Diaspora Art in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

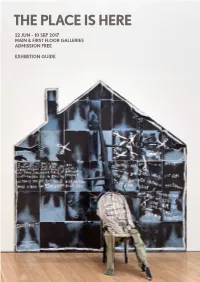

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Zarina Bhimji

Zarina Bhimji ‘My work is not about the actual facts but about the echo they create, the marks, the gestures and the sound. This is what excites me.’ Zarina Bhimji Landscapes and buildings bearing the traces of time are the protagonists in British artist Zarina Bhimji’s poetic photographs and large-scale film installations. Devoid of any human presence they are intentionally open-ended and ambiguous. This first major survey exhibition traces 25 years of Bhimji’s career. It opens with two seascapes taken in Zanzibar and a selection of images from the Love series (1998–2007), which were shot in Uganda. The photographs are grounded in meticulous research but, like much of Bhimji’s work, are distanced from historic and political specificity. The premiere of Yellow Patch (2011), Bhimji’s ambitious new film shot on location in India, takes centre stage in Gallery 1. This is complemented by the artist’s debut filmOut of Blue (2002), an arresting visual journey across Uganda, which is on view in Gallery 8 upstairs. Two early commissions are presented together here for the first time:She Loved to Breathe - Pure Silence (1987), an installation of photographs suspended from the ceiling above a field of spices, and Cleaning the Garden (1998) which is made up from photographs, light boxes and mirrors. Zarina Bhimji was born in Mbarara, Uganda in 1963 to Indian parents, and moved to Britain in 1974, two years after the expulsion of Uganda’s Asian community under the dictatorship of Idi Amin. She was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2007. -

Full Version

CURRICULUM VITAE Name Zarina Bhimji Email [email protected] Web www.zarinabhimji.com EDUCATION 1987 - 1989 Slade School of Fine Art University College London, London, UK [Higher Diploma in Fine Art] 1983 - 1986 Goldsmiths' College University of London, London, UK [B.A. Fine Art] 1982 - 1983 Leicester Polytechnic, Leicester, UK [Art Foundation] SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 - Zarina Bhimji, Sharjah Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE 2018 - Spotlight, Tate Britain, London, UK * 2015 - Zarina Bhimji: Jangbar, NAE, Nottingham, UK * 2012 - Zarina Bhimji, Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK * 2012 - Yellow Patch, The New Gallery, Walsall, UK * 2012 - Zarina Bhimji, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern, Switzerland * 2012 - Zarina Bhimji, de Appel, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2009 - Zarina Bhimji, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA 2007 - Zarina Bhimji, Haunch of Venison, Zürich, Switzerland 2007 - Galerie Lumen Travo, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2006 - Zarina Bhimji, Haunch of Venison, London, UK 2004 - Zarina Bhimji, Archive Season, inIVA, London, UK 2003 - Matrix 150, Wadsworth Athenium Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, USA * 2003 - Art Now, Tate Britain, London, UK* 2001 - Talwar Gallery, New York, USA 1998 - Cleaning the Garden - Harewood House, Terrace Gallery, Leeds, UK * 1995 - Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK * 1992 - I will always be here - Ikon Gallery, Birmingham & tour, UK * 1989 - Tom Allen Community Art Centre, London, UK * Catalogue available Page 1 SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2020 - Lahore Biennale 02, Lahore Biennale Foundation, Lahore, Pakistan -

An Unremitting Yet Gentle Point of View

Press Release Zarina Bhimji Berne, 30.05.2012 01.06. – 02.09.2012 An Unremitting yet Gentle Point of View In collaboration with the renowned Whitechapel Gallery in London, the Kunstmuseum Bern is presenting the first retrospective on British photographer, filmmaker, and installation artist Zarina Bhimji. With a criticism marked by gentleness and a poetic touch, Zarina Bhimji tackles the complex subjects of migration, globalization, and post-colonial history. The artist was born in 1963 as daughter to parents of Indian descent living in Uganda, where she grew up until Idi Amin’s expulsion of the country’s Indian minority. Zarina Bhimji completed her art studies in London. She has been invited to participate in many international group exhibitions and was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2007. A poetic search for traces of the past Zarina Bhimji’s work is strongly marked by her personal experiences of exile and her diverse cultural background. Her poetic films and photographs are documents of her search for traces of the past. The artist constructs fragmented narratives by interweaving personal experience and intuition with facts concerning the countries of her origins and their post-colonial history. In doing so, she formulates a subjective view of the present situation in three continents (Europe, Africa, Asia) and unveils the complex entwinement of culture, ethnicity, and politics. In her art, Bhimji does not articulate her bonds to Africa, India, and Europe by way of accusations, political analyses, or blame. Instead she engages with locations and landscapes related to her background while exploring their beauties. Emotional honing in on truth Bhimji addresses history and truth via poetry and beauty. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Zarina Bhimji

CURRICULUM VITAE Zarina Bhimji EDUCATION 1987 - 1989 - Slade School of Fine Art University College London 1983 - 1986 - Goldsmiths' College University of London 1982 - 1983 - Leicester Polytechnic SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2007 - Zarina Bhimji, Haunch of Venison, Zürich, Switzerland 2007 - Galerie Lumen Travo, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2006 - Zarina Bhimji, Haunch of Venison, London, UK 2004 - Institute of International Visual Arts, London, UK 2003 - Matrix, Wadsworth Athenium Museum of Art, Hartford, CN, USA * 2003 - Art Now, Tate Britain, London, UK * 2001 - Talwar Gallery, New York, USA 1998 - Cleaning the Garden - Harewood House, Terrace Gallery, Leeds * 1995 - Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, Cambridge * 1992 - I will always be here - Ikon Gallery, Birmingham & tour * SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2007 ‐ Turner Prize 2007 Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, UK 2006 ‐ How to Improve the World: 60 Years of British Art Hayward gallery, London, UK * - Zones of Contact, Biennale of Sydney, Sydney, Australia * - Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, ICP, New York, USA. * 2005 - 50 Years of Documenta 1965-2005, Kassel, Germany * - British Art Show 6, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead & UK tour * - Experiments with Truth The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, USA * 2004 - strangerthanfiction Leeds City Art Gallery,UK.* - In Our Time - Works from the Moderna Museet Collection, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden * 2003 - Istanbul Biennale, Istanbul, Turkey * - Fault Lines, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy * - Istanbul -

Curriculum Vitae Chila Kumari Burman

! ! Curriculum Vitae Chila Kumari Burman Brought up in Liverpool and educated at the Slade School of Art in London, Chila Kumari Burman has worked experimentally across printmaking, painting, sculpture, photography and film since the mid-1980s. She draws on fine and pop art imagery in intricate multi- layered works which explore Asian femininity and her personal family history, and where Bollywood bling merges with childhood memories. The Bindi Girls are a series of female figures composed almost entirely of colourful and glittery bindis, gems and crystals. Meticulously handcrafted and embellished, they suggest a powerful yet playful femininity. From bindis and other fashion accessories to ice cream cones and ice lolly wrappers, Chila often uses everyday materials in her work, giving new meaning to items which others may see as worthless, cheap or kitsch. Ice Cream has a particular significance in her work and references her childhood in Liverpool where her father, who arrived as an immigrant from India in the 1950s, owned an ice cream van and was a popular figure as he drove around selling ice cream for over thirty years. As well as paying homage to her father, her Ice Cream works evoke the awakening of her own creative spirit when as a child she would help out in the ice cream van and became immersed in a world of colour, flavour and materials. Chila Kumari Burman’s work is held in a number of public and private collections including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Wellcome Trust in London, and the Devi Foundation in New Delhi. -

On Fabric of Protest, Terra/Nina Edge and Turner Prize 2007, Alex

A Side. B Side. Double AA Side. On Fabric of Protest, Terra/Nina Edge and Turner Prize 2007. Alex Hetherington Site and Tate Liverpool, Albert Dock, Liverpool, Merseyside L3 4BB Give sympathy for the 7” vinyl record: two recordings bound by alienated separation; bound together by a conjoined synthetic whole. A Side is the main attraction, glistening with pop pulling power, B side a sonic shadow, a slighter song waiting for airplay, waiting for the needle to touch, to stimulate its resonance. The vinyl recording is a metaphor for duality and the interchangeable, inhabits its own vocabulary of hierarchies, is its own mechanism imbued with codes of manufacturing, modernity, consumerism and the moment. It is a continuous sonic cloth, labouring under the scrutiny of a virulent yet passive needle. This text hopes to conjoin in a similar way two different yet totally analogous exhibitions recently or currently on view at the Albert Dock in Liverpool, England. Fabric of Protest at Site and in particular the work Terra by Liverpool-based visual artist Nina Edge, and the Turner Prize 2007 featuring Mark Wallinger, Nathan Coley, Mike Nelson and Zarina Bhimji, which in celebration of Liverpool’s Capital of Culture 2008 has been installed at the city’s Tate Gallery, its first presentation outside of London in its 24-year history. Fabric of Protest, curated by John Byrne, and Paul Domela of JMU and Liverpool Biennial articulates a kind of ‘menace’ of textiles, the burgeoning meaning of surface, decoration, material and dress whether political, religious or domestic. It assembles a group of artists interested in the concoction of controversies, implications and separations that surround the vocabulary of worn and adorn. -

Researching Exhibitions of South Asian Women Artists in Britain in the 1980S

Researching Exhibitions of South Asian Women Artists in Britain in the 1980s Alice Correia Abstract This paper narrates the author’s research methodologies and findings relating to her ongoing project, Articulating British Asian Art Histories. With a specific focus on four exhibitions of South Asian women artists uringd the 1980s and early 1990s, it provides an overview of her primary and secondary research, and presents archival material, which cumulatively gives a richer understanding of the aesthetic and political aims of exhibitors, and the contexts in which they were working. Exhibitions of exclusively women artists of South Asian heritage were rare during this period, but close visual analysis of individual exhibitions and artworks reveals an active engagement with the specificities of the female, British-Asian experience. This article is accompanied by two downloadable resources: a complete copy of the Numaish exhibition catalogue (Fig. 15) and a copy of the exhibition pamphlet for Jagrati (Fig. 22). Authors Research Fellow at the University of Salford Acknowledgements I would like to thank Sarah Victoria Turner and Hammad Nasar for inviting me to present my research at the conference, Showing, Telling, Seeing: Exhibiting South Asia in Britain 1900 to Now, and for their continued support whilst developing this article. My research has been richly enhanced by conversations with numerous artists, especially Chila Kumari Burman, Jagjit Chuhan, Nina Edge, Bhajan Hunjan, and Symrath Patti, who also provided materials from their personal archives for reproduction here. Research for this paper was undertaken during a Mid-Career Fellowship funded by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, and I am grateful to all at the Centre for their intellectual and practical support. -

From Politics to Poetry Zarina Bhimji in Conversation with Achim Borchardt-Hume and Kathleen Bühler

Media Kit Zarina Bhimji From Politics to Poetry 01.06. – 02.09.2012 Zarina Bhimji in Conversation with Achim Borchardt-Hume and Kathleen Bühler From Politics to Poetry Zarina Bhimji in Conversation with Achim Borchardt-Hume and Kathleen Bühler Achim Borchardt-Hume: What drives you to make the work you make and what drives you to give it the form that it takes; what is that relationship? Zarina Bhimji: I don’t know fully. Working as an artist, I am interested in lots of different things: anthropology, sociology, painting, poetry, history and so many other subjects. Part of the drive is being able to delve into all these different ways of thinking and to respond to them through my own forms. I do so by way of a set of constellations. Research gives me time to think about ideas of gestures, shapes and light. After this process, a structure for the work develops. I search instinctively for how to form a narrative through aesthetics. The process is like having a toolbox to carefully examine sounds, light, texture, fictional possibilities and what I think of as ‘camera presence’. Kathleen Bühler: What made you decide to become an artist? ZB The idea of making art formed at school through my interests and experiences as I was growing up. I subscribed to the feminist magazine Spare Rib and a few years later I joined the Labour Party. Then I went to Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp where women were protesting in a peaceful manner. They hung children’s clothes on barbed wire fences, which to me appeared like installations. -

Protest Panel 2: Performance Can Do

ORIGINAL ARTWORKS: CAN DO: Photographs and other Set of orginal artworks commissioned 1 2 3 4 5 6 material from the Women’s Art 1 2 3 4 5 by the Women’s Art Magazine under Library Magazine Archive the editorship of Sally Townsend to appear on the covers of 6 9 13 1. Sandra Blow, Christmas 93, 1993, 22 x 18.5 cm (Magazine 8 11 12 No. 55) issues 55 to 61 (excluding the special LIST OF WORKS 10 19 2. Virginia Ryan Izzo, Sarajevo drawing, 1993, 22.5 x 19 cm photography issure 59 whose cover 7 (Magazine No. 56) 3. Eileen Cooper, Storyteller, 1994, 22 x 18.5 cm (Magazine featured the work of Cindy Sherman). 15 No. 57) 16 20 4. Rose Gerrard, Reconstructing the “Man”-Stream: See 14 17 18 Paradise, 1994, 22 x 18.5 cm (Magazine No. 58) PANEL 1: PROTEST 5. Chila Burman, Untitled, 22 x 18.5 cm (Magazine No. 60) 6. Jenny Saville in collaboration with Glen Luchford, Untitled, 22 x 18.5 cm (Magazine No. 61) 1. Loraine Leeson and Peter Dunn, What’s Going On 3, 1982. 9. Lorna Green, Water, Earth into Growth, 1988, sculpture, Docklands Community Poster Project. Third image of the first green bottles. Exhibition: Islington Green, London. sequence of photo-murals exploring issues surrounding the 10. Roxane Permar, Extraction, 1991, installation (detail): re-development of the London Docklands from the viewpoint Brixton Art Gallery, London. of local communities. 11. Gabriella Miller, Power of Powerlessness, no date, tapestry. 2. Joyce Agee, Balloons, Primrose Hill Fair, 1980. -

Turner Prize 2007 Teachers' Pack

Tate Liverpool EEducatorducatorducatorssss’P’P’P’Packack malcolmmorley howardhodgkin gilbert&george richarddea con tonycragg richardlong anishkapoor grenvilledavey rache whiteread antonygormley damienhirst douglasgordon gillia nwearing chrisofili stevemcqueen wolfgangtilmans martinc eed keithtyson graysonperry jeremydeller simonstarling to mmaabts malcolmmorley howardhodgkin gilbert&george r icharddeacon tonycragg richardlong anishkapoorgrenville edavey rachelwhiteread antonygormley damienhirst dougl asgordon gillianwearing chrisofili stevemcqueen wolfgang gtilmans martincreedkeithtyson graysonperry jeremydelle rsimonstarling tommaabts malcolmmorley howardhodkin gilbert&george richarddeacon tonycragg richardlong anis hkapoor grenvilledavey rachelwhiteread antonygormley d amienhirst douglasgordon gillianwearing chrisofili stevem cqueen wolfgangtilmans martincreed keithtyson graysonp erry jeremydeller simonstarling tommaabts malcolmmorle The Turner Prize Since 1984 this contemporary and often controversial British art award has been presented at Tate Britain. For the first time the prize is to be held outside of London in acknowledgement of Liverpool’s status of European Capital of Culture in 2008. The Turner Prize, with £25,000 going to the winner and £5,000 each for the other shortlisted artists, is awarded to a British artist undeunderr fifty for an outstanding exhibitionexhibition or other prespresentationentation of their work in the preceding twelve months. It is intended to promote public discussion of new developments in contemporary -

HENI Publishing Catalogue 2019

Since its inception in 2009, HENI Publishing has worked closely with artists and authors of the highest calibre across a wide range of titles, from major trade publications to artists’ books and limited editions. Among our new titles for 2019 we are delighted to be publishing the collected conversations of two titans of the contemporary art world in Hans Ulrich Obrist’s The Richter Interviews; a new monograph on New York- based British artist Shantell Martin, the first critical book to showcase her multi-faceted practice; a beautiful and intimate survey of nude photography by Mary McCartney, complete with an artist’s special edition; an artist’s book by Cathy Wilkes to accompany her exhibition at the British Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale; and the first of two volumes of the collected writings on art by one of the world’s leading critics and curators, Robert Storr. To find out more about our books – as well as HENI’s work across editions, film, photography and more – visit our website: www.heni.com Contents New Titles 2019 5 Recent Titles & Backlist 29 List of Illustrations 45 Index 46 Sales & Distribution 48 New Titles 2019 Mary McCartney: Paris Nude Essay by Charlotte Jansen Paris Nude presents for the first time a new body of work by the celebrated British photographer Mary McCartney. Over the course of two days in summer 2016, McCartney stayed with her subject Phyllis Wang at her St Germain apartment in Paris, photographing Wang in the nude to produce an extraordinary and intimate series of images. A mixture of black-and-white and colour, the delicate photo- graphs collected here showcase the trust required from both subject and photographer.