Black British Art History Some Considerations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

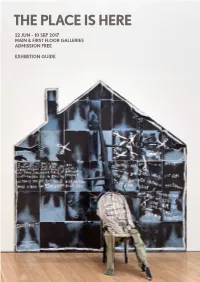

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 1:30 PM - 2:45 PM Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Shelby Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Miller, Shelby, "Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art" (2017). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/004/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Shelby Miller Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Bibliographic Style: MLA 1 How does one define the concepts of space and place and further translate those theories to the Caribbean region? Through abstract modes of representation, artists from these islands can shed light on these concepts in their work. Involute theories can be discussed in order to illuminate the larger Caribbean space and all of its components in abstract art. The trialectics of space theory deals with three important factors that include the physical, cognitive, and experienced space. All three of these aspects can be displayed in abstract artwork from this region. By analyzing this theory, one can understand why Caribbean artists reverted to the abstract style—as a means of resisting the cultural establishments of the West. To begin, it is important to differentiate the concepts of space and place from the other. -

To Read the Abstracts and Biographies for This Panel

Abstracts and Biographies Panel 1: Operable Infrastructures Chair: Mora Beauchamp-Byrd Panel Chair: Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd, Ph.D., is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Art and Design at The University of Tampa, where she teaches courses in Modern & Contemporary Art and in Museum Studies. An art historian, curator, and arts administrator, she specializes in the art of the African Diaspora; American Art; Modern and Contemporary art, including a focus on late twentieth-century British art; Museum & Curatorial studies; and representations of race, class and gender in American comics. She has organized numerous exhibitions, including Transforming the Crown: African, Asian and Caribbean Artists in Britain, 1966- 1996; Picturing Creole New Orleans: The Photographs of Arthur P. Bedou, and Little Nemo’s Progress: Animation and Contemporary Art. She is currently completing a manuscript that examines David Hockney, Lubaina Himid, and Paula Rego’s appropriations of William Hogarth’s eighteenth-century satirical narratives. From Resistance to Institution: The History of Autograph ABP from 1988 to 2007 Taous R. Dahmani Since its creation in 1988, Autograph ABP has aimed at defending the work and supporting author-photographers from Caribbean, African and Indian diasporas, first in England and then beyond. Initially a utopian idea, then a very practical and political project and finally a hybrid institution, Autograph ABP has presented itself in turn as an association, an agency, an archive, a research centre, a publishing house and an exhibition space. To tell the story of Autograph ABP is to tell the story of its evolution, that of a militant space having become a cultural institution. -

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990 Medium: Lightboxes with Duratran prints Size: 5 parts, total, 190.5 x 121.9cm Collection: Arts Council ACC7/1990 1. Art historical terms and concepts Subject Matter Traditionally portraits depicted named individuals for purposes of commemoration and/or propaganda. In the past black figures were rarely portrayed in Western art unless within group portraits where they were often used as a visual and social foil to the main subject. Rodney adopted the portrait to explore issues around black masculine identity - in this case the stereotype of young black men as a ‘public enemy’. The title ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ comes from the writings of cultural theorist Stuart Hall about media representations of young black men as an ‘icon of danger’, a metaphor for all the ills of society. Rodney said of this Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk work: “I’ve been working for some time on a series…about a black male image, both in the media and black self-perception. I wanted to make a self-portrait [though] I didn’t want to produce a picture with an image of myself in it. It would be far too heroic considering the subject matter. I wanted generic black men, a group of faces that represented in a stereotypical way black man as ‘the other’, a black man as the enemy within the body politic” (1991). Rodney is asking the question: ‘Is this what people see when they see me?’ He has created a kind of ‘everyman’ for every black man, a heterogeneous identity. -

Stuart Hall Bibliography 27-02-2018

Stuart Hall (3 February 1932 – 10 February 2014) Editor — Universities & Left Review, 1957–1959. — New Left Review, 1960–1961. — Soundings, 1995–2014. Publications (in chronological order) (1953–2014) Publications are given in the following order: sole authored works first, in alphabetical order. Joint authored works are then listed, marked ‘with’, and listed in order of co- author’s surname, and then in alphabetical order. Audio-visual material includes radio and television broadcasts (listed by date of first transmission), and film (listed by date of first showing). 1953 — ‘Our Literary Heritage’, The Daily Gleaner, (3 January 1953), p.? 1955 — ‘Lamming, Selvon and Some Trends in the West Indian Novel’, Bim, vol. 6, no. 23 (December 1955), 172–78. — ‘Two Poems’ [‘London: Impasse by Vauxhall Bridge’ and ‘Impasse: Cities to Music Perhaps’], BIM, vol. 6, no. 23 (December 1955), 150–151. 1956 — ‘Crisis of Conscience’, Oxford Clarion, vol. 1, no. 2 (Trinity Term 1956), 6–9. — ‘The Ground is Boggy in Left Field!’ Oxford Clarion, vol. 1, no 3 (Michaelmas Term, 1956), 10–12. 1 — ‘Oh, Young Men’ (Extract from “New Landscapes for Aereas”), in Edna Manley (ed.), Focus: Jamaica, 1956 (Kingston/Mona: The Extra-Mural Department of University College of the West Indies, 1956), p. 181. — ‘Thus, At the Crossroads’ (Extract from “New Landscapes for Aereas”), in Edna Manley (ed.), Focus: Jamaica, 1956 (Kingston/Mona: The Extra-Mural Department of University College of the West Indies, 1956), p. 180. — with executive members of the Oxford Union Society, ‘Letter: Christmas Card Aid’, The Times, no. 53709 (8 December 1956), 7. 1957 — ‘Editorial: “Revaluations”’, Oxford Clarion: Journal of the Oxford University Labour Club, vol. -

Frank Bowling Cv

FRANK BOWLING CV Born 1934, Bartica, Essequibo, British Guiana Lives and works in London, UK EDUCATION 1959-1962 Royal College of Art, London, UK 1960 (Autumn term) Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1958-1959 (1 term) City and Guilds, London, UK 1957 (1-2 terms) Regent Street Polytechnic, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Image in Revolt, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1963 Frank Bowling, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1966 Frank Bowling, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1971 Frank Bowling, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, USA 1973 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1973-1974 Frank Bowling, Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, New York, USA 1974 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1975 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1976 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Watson/de Nagy and Co, Houston, Texas, USA 1977 Frank Bowling: Selected Paintings 1967-77, Acme Gallery, London, UK Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1979 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1980 Frank Bowling, New Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1981 Frank Bowling Shilderijn, Vecu, Antwerp, Belgium 1982 Frank Bowling: Current Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, -

A Way of Life Considering and Curating the Sainsbury African

A Way of Life Considering and Curating the Sainsbury African Galleries Christopher James Spring A Context Statement submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements For the award of Doctorate in Professional Studies by Public Works Institute for Work Based Learning Middlesex University United Kingdom 2015 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Summary and Introduction 3 Part 1: Laying the Foundations 13 Part 2: The Sainsbury African Galleries 30 Part 3: The Forum 44 An ending, a beginning 73 Bibliography 77 Appendices 1. The MoM in reviews of the African Galleries 83 2. The African Galleries Reviewed 84 3. Chris Spring bibliography 86 4. Fieldwork 91 5. Exhibitions 91 6. Major Acquisitions 92 7. Festivals and Conferences 93 List of Images ‘Two Towers’, 2008, p.4, Kester and the Throne, p.10, The Tree of Life, p.11, Register, 1988, p.19, House in Farafra Oasis, 1991, p.22, ‘Big Masquerade’ by Sokari Douglas Camp, 1995, (copyright SDC and the Trustees of the BM) p.23, ‘Meriel’, 1998, p.25, Weaver in Mahdia, 1997, p.28, ‘Vessel’ by Magdalene Odundo, 2000, (copyright MO and Trustees of the BM), p.33, Kenya cricket shirt, 2001, p.39, The African Galleries Introduction, 2004, p.46, Mahdaoui’s ‘Joussour’, 1997 (copyright Nja Mahdaoui), p.48, In Temacine, 2013, p.49, Ifitry, Morocco, 2013, p.50, ‘Hujui Kitu’ kanga, 2003,(copyright Trustees of the BM),p.53, Kester on the Throne, 2000, (copyright Kester and Christian Aid) The Throne of Weapons, 2002,(copyright Kester and the Trustees of the BM),p.54, Tree of Life in Peace Park, 2004,(copyright David -

1.8. Thesis Objectives

Elevated blood pressure and hypertension in South Asian children: A mixed-methods analysis exploring associated factors and behavioural influences by Adeleke Fowokan MPH, University of Essex, 2013 BSc, University of Lagos, 2010 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biomedical Physiology and Kinesiology Faculty of Science © Adeleke Fowokan 2019 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2019 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Adeleke Fowokan Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title: Elevated blood pressure and hypertension in South Asian children: A mixed-methods analysis exploring associated factors and behavioural influences Examining Committee: Chair: Sam Doesburg Associate Professor Scott Lear Senior Supervisor Professor Miriam Rosin Supervisor Professor Charlotte Waddell Supervisor Professor Faculty of Health Sciences Zubin Punthakee Supervisor Associate Professor, McMaster University Scott Venners Internal Examiner Associate Professor Faculty of Health Sciences Namratha Kandula External Examiner Associate Professor Department of Medicine Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University Date Defended/Approved: October 16, 2019 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract The overarching objective of this PhD thesis was to develop a better understanding of how broad-based (physiological, lifestyle, social and cultural) factors, influence -

Thurs 25 March Additional Programme Information 090310

From the Margins to the Core? Conference Additional Programme Information Day 2 - Thursday 25 March 2010 Connecting or Competing Equalities? 09.30-09.50 Title: Diversity and cultural policy This presentation will suggest how contemporary concerns with diversity and difference present particular challenges for mainstream art historical and curatorial practice. It will locate Dr Leon Wainwright’s own practice, which overlaps historical research, collaborations with museums and galleries, and curatorial work. Briefly, he will set out the broader intellectual background on which the concept of ‘margins and core’ has emerged in the academy, and suggest why opportunities for exploring transnationalism may also become the site of ‘competing equalities’. The examples for this range from the institutional life in Britain of World Art Studies, and two exhibitions in Liverpool in 2010. Chair: Dr Jo Littler, Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies at Middlesex University As well as being the Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies at Middlesex University, Jo Littler is co-editor, with Roshi Naidoo, of The Politics of Heritage: The Legacies of Race (Routledge 2005), author of Radical Consumption? Shopping for change in contemporary culture (Open University Press, 2009) and an associate editor of Soundings. Speaker: Dr Leon Wainwright, Senior Lecturer in History, Art & Design, Manchester Metropolitan University Leon Wainwright is Senior Lecturer in the History of Art and Design at Manchester Metropolitan University, Visiting Fellow at the Yale Center for British Art, a member of the editorial board of the journal Third Text, and Guest Curator, with Reyahn King, of Aubrey Williams Atlantic Fire (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, 2010). -

ART of the CARIBBEAN ‘A Wonderful Set of Images Which Helps to Re-Define the Boundaries of the Caribbean for a British Onlooker

PartGOODWILL 1 — Caribbean TEACHING art history GUIDE — the essential teaching resource for craft, design and culture LIST OF CONTENTS ART OF THE CARIBBEAN ‘A wonderful set of images which helps to re-define the boundaries of the Caribbean for a British onlooker. The visual art is supported by concise and effective background material, both historical and textual’. Dr. Paul Dash, Department of Education, Goldsmith’s College. LIST OF CONTENTS PART 3 This set explores Caribbean culture Looking at the pictures and its arresting visual art Unknown Taino Artist, Jamaica, Avian Figure Introduction Isaac Mendes Belisario, Jamaica, House John Canoe Map of the Caribbean Georges Liautaud, Haiti, Le Major Jonc Time-line Annalee Davis, Barbados, This Land of Mine: Past, Present and Future John Dunkley, Jamaica, Banana Plantation Wifredo Lam, Cuba, The Chair PART 1 Raul Martinez, Cuba, Cuba Caribbean art history Edna Manley, England/Jamaica, The Voice Colonial Cuba Unknown Djuka Artist, Suriname, Apinti Drum Cuban art since1902 Everald Brown, Jamaica, Instrument for Four People Stanley Greaves Caribbean Man No. 2 Colonial Saint-Domingue Aubrey Williams, Guyana/England, Shostakovich 3rd Symphony Cecil Baugh, Jamaica, Global Vase with Egyptian blue running glaze Haitian art since 1811 Stephanie Correia, Guyana, Tuma 1 Dutch West-Indian colonies Philip Moore, Guyana, Bat and Ball Fantasy British West Indies Ronald Moody, Jamaica/England, Midonz (Goddess of Transmutation) English-speaking Caribbean: Jamaica, Stanley Greaves, Guyana/Barbados, Caribbean Man No. 2 Barbados, Guyana, Trinidad, Wilson Bigaud, Haiti, Zombies Ras Aykem-i Ramsay, Barbados, Moses For easy navigation blue signals a link to a Caribbean-born artists in Britain Pen Cayetano, Belize, A Belizean History: Triumph of Unity relevant page. -

PDF File, 1.7 MB

Black History Events Report – Victoria and Albert Museum 2003 Analysis of Black History Events held at the Victoria and Albert Museum during Black History Month Full Report (February 2003) Prepared By The Market Research Group (MRG), Bournemouth University, On Behalf of The Victoria and Albert Museum www.themarketresearchgroup.co.uk Page 1 Black History Events Report – Victoria and Albert Museum 2003 CONTENT OF REPORT CONTENT OF REPORT............................................................... 2 1: Executive Summary .................................................................. 4 1.1: Event analysis (4.1.) Both questionnaires. ..........................................................4 1.2: Demographics (4.3.)...........................................................................................5 2: Introduction ............................................................................... 7 2.1: The Black History Events ....................................................................................7 2.3: The Market Research Group (MRG) ...................................................................7 2.4: Project Aims & Objectives ...................................................................................7 2.4.1: Project Aims........................................................................................................................7 2.4.2: Project Objectives ...............................................................................................................7 3: Methodology............................................................................. -

LOCKE, DONALD. Donald Locke Papers, 1953-2016

LOCKE, DONALD. Donald Locke papers, 1953-2016 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Locke, Donald. Title: Donald Locke papers, 1953-2016 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1440 Extent: 19.375 linear feet (19 boxes), AV Masters: .25 linear feet (1 box), and 9.92 GB born digital materials (3,099 files). Abstract: Papers of Guyanese artist Donald Locke consisting of manuscripts, correspondence, subject files, photographs, slides, ephemera, catalogs, and printed material dating from 1953-2016. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study.