Two-Days National Workshop-Cum-Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Affairs= 07-09-2020

CURRENT AFFAIRS= 07-09-2020 KESAVANANDA BHARATI Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed grief over the passing away of Kesavananda Bharati Ji. About: Kesavananda Bharati was the head seer of the Edneer Mutt in Kasaragod district of Kerala since 1961. He left his signature in one of the significant rulings of the Supreme Court when he challenged the Kerala land reforms legislation in 1970. The Kesavananda Bharati judgement, is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of India that outlined the basic structure doctrine of the Constitution. Justice Hans Raj Khanna asserted through the Basic Structure doctrine that the constitution possesses a basic structure of constitutional principles and values. The doctrine forms the basis of power of the Indian judiciary to review and override amendments to the Constitution of India enacted by the Indian parliament. MOPLAH REBELLION A report submitted to the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) in 2016 had recommended the removal of the Wagon Tragedy victims and Malabar Rebellion leaders Ali Musliyar and Variamkunnath Ahmad Haji, and Haji’s two brothers from a book on martyrs of India’s freedom struggle. CROSS & CLIMB 2019 1 About: The report sought the removal of names of 387 ‘Moplah rioters’ from the list of martyrs. The book, Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle 1857-1947, was released by Prime Minister Narendra Modi last week. The report describes Haji as the “notorious Moplah Riot leader” and a “hardcore criminal,” who “killed innumerable innocent Hindu men, women, and children during the 1921 Moplah Riot, and deposited their bodies in a well, locally known as Thoovoor Kinar”. -

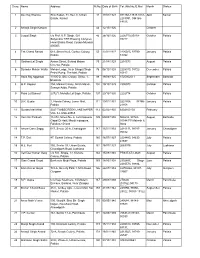

Directory of SBPROA Membership

Sr.no. Name Address M.No. Date of Birth Tel. /Mb.No./E.Mail Month Station 1 Dev Raj Sharma Shiv Sadan, 91, Sec. 6, Urban 17 17/04/1924 094168-14515 0184- April Karnal Estate, Karnal 2283091, 094168- 14515 2 Amarjit Singh Kanwar 44 12/10/1926 October 3 Jaspal Singh c/o Prof. K.P. Singh, 501 46 28/10/1926 2206719,95019- October Patiala Satyendra TIFR Housing Complex, 78227 Homi Bhaba Road, Colaba-Mumbai- 400005 4 Tek Chand Bansal 618, Street No.6, Gurbux Colony, 55 12/01/1927 2226025, 97790- January Patiala Patiala 18992 5 Girdhari Lal Singla Araian Street, Behind Malwa 75 21/08/1929 2201573 August Patiala Cinema, Patiala 6 Surinder Mohan Walia Mohan Lodge, Near Bhagat Singh 76 06/12/1928 2228310, 98722- December Patiala Petrol Pump, The Mall, Patiala 10817 7 Hans Raj Aggarwal 13305-D, Shiv Colony, St No. 1, 98 19/09/1925 8725902011 September Bathnda Bhatinda 8 O.P. Kapoor 204, Markal Colony, Mirch Mandi, 102 19/10/1929 2305070 October Patiala Sanauri Adda, Patiala 9 Piara Lal Bansal 2372/1, Mohalla Lal Bagh, Patiala 107 20/10/1930 2202714 October Patiala 10 D.R. Gupta 1, Narula Colony, Lower Mall, 111 10/01/1931 2221858. 98766- January Patiala Patiala 21858 11 Gurdas Mal Mittal 3347 TIMBECREEK LANE NAPER 112 02/02/1930 6304160102 February VILL ILL USA-60565 12 Hari Om Parkash 11/272, Street No. 6, Left Opposite 135 09/08/1930 500233, 98724- August Bathinda Gopal Di Hatti, Manjit Indarpura, 91544 PP Mahesh & Faridkot-151203 Sons 13 Ishwar Dass Saggu 647, Sector 20-A, Chandigarh 147 15/01/1933 2281111, 98787- January Chandigarh 70882 14 T.P. -

Parliamentary Documentation Vol. XXXVIII 1-15 July 2012 No.13

Parliamentary Documentation Vol. XXXVIII 1-15 July 2012 No.13 AGRICULTURE -(INDIA) 1 MAHAJAN, Ashwani Where's the action plan? DECCAN HERALD (BANGALORE), 2012(10.7.2012) Raises concern over the possible impact of poor monsoon on agriculture in India. ** Agriculture-(India). -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 2 Beware of the invasion. MONTHLY PUBLIC OPINION SURVEYS (NEW DELHI), V.57(No.9), 2012(Jun, 2012): P.8-9 Discusses the implications of cultivating genetically modified food crop in the country. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Research. 3 VENUGOPALAN, M V and Others Productivity and nitrogen-use efficiency yardsticks in conventional and Bt. Cotton hybrids on rainfed Vertisols. INDIAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES (NEW DELHI), V.82 (No.7), 2012(Jul, 2012): P.81-84 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Research. 4 VIJAYAN, V S Let's farm along with nature, not against it. TIMES OF INDIA (MUMBAI), 2012(15.7.2012) Highlights the recommendations made in the "M S Swaminathan Task Force Report on agricultural biodiversity". ** Agriculture-Agricultural Research. -AGRICULTURE POLICY-(INDIA-ASSAM) 5 DAS, Manmohan Revolution needed in agriculture. ASSAM TRIBUNE (GUWAHATI), 2012(4.7.2012) Emphasises the need to promote Agriculture Sector and rural industrialisation in Assam. ** Agriculture-Agriculture Policy-(India-Assam); Rural Industry. ** - Keywords 1 -FARMS AND FARMERS 6 DWAIPAYAN Small tea growers and Tea Board package. ASSAM TRIBUNE (GUWAHATI), 2012(1.7.2012) Expresses concern over plight of small tea growers in Assam. ** Agriculture-Farms and Farmers; Tea. 7 MISHRA, Alok K N Congress lends support to Nagri land fight. TIMES OF INDIA (MUMBAI), 2012(9.7.2012) Expresses concern over plight of the farmers living at Nagri village in Jharkhand. -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

Annual Report 2007-2008

The Supreme Court of India The Supreme Court of India ANNUAL REPORT 2007-2008 (Published by the Supreme Court of India) EDITORIAL COMMITTEE: For Official use Only Hon’ble Mr. Justice S.B. Sinha Hon’ble Mr. Justice R.V. Raveendran COPYRIGHT© 2008 : THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Hon’ble Mr. Justice D.K. Jain Publisher : The Supreme Court of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be New Delhi-110001 reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted Website – http://supremecourtofindia.nic.in in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, Book : Annual Report 2007-2008 photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior (Contents mainly relate to 1.10.2007 to permission in writing of the copyright owner. 30-09.2008) Printed at I G Printers Pvt. Ltd. Tel. No: 011-26810297, 26817927 Photography: J.S. Studio (Sudeep Jain) 9810220385 (M) CONTENTS PAGE S. DESCRIPTION NO. NOS. 1. Hon’ble Chief Justice of India & Hon’ble Judges of Supreme Court ................................................................................. 9 2. An overview .......................................................................................... 39 The History Supreme Court – At present Court Building Lawyers’ Chambers Supreme Court Museum Retired Hon’ble Chief Justices Retired Hon’ble Judges 3. Jurisdiction .......................................................................................... 49 Original Appellate Advisory Review Curative Public Interest Litigation 4. The Bar ............................................................................................... -

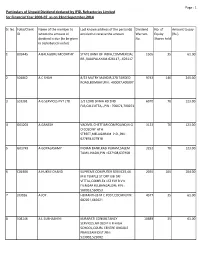

List of Unpaid and Or Unclaimed Dividend FY 2006-07

Page : 1 Particulars of Unpaid Dividend declared by IFGL Refractories Limited for Financial Year 2006-07 as on 22nd Sepetmber,2014 Sl. No. Folio/Client Name of the member to Last known address of the person(s) Dividend No. of Amount to pay ID whom the amount of entitled to receive the amount Warrant Equity (Rs.) dividend is due (to be given No. Shares held in alphabetical order) 1 B03445 A BALAGURU MOORTHY STATE BANK OF INDIA,COMMERCIAL 1505 35 61.00 BR.,RAJAPALAYAM-626117,-,626117 2 S01862 A C SHAH 8/23 MATRY MANDIR,278 TARDEO 9743 140 245.00 ROAD,BOMBAY,PIN : 400007,400007 3 L01301 A G SERVICES PVT LTD 1/2 LORD SINHA RD 2ND 6070 70 123.00 FLR,CALCUTTA,-,PIN : 700071,700071 4 G01203 A GANESH VADIVEL CHETTIAR COMPOUND,N G 3123 70 123.00 O COLONY 6TH STREET,MELAGARAM P.O.,PIN : 627818,627818 5 G01749 A GOPALASAMY INDIAN BANK,RASI PURAM,SALEM 3252 70 123.00 TAMIL NADU,PIN : 637408,637408 6 C01906 A HUKMI CHAND SUPREME COMPUTER SERVICES,44 2055 105 184.00 M K TEMPLE ST OPP UBI SRI VITTAL,COMPLEX 1ST FLR B V K IYENGAR RD,BANGALORE PIN : 560053,560053 7 J03026 A JOY HEMANTH,B M C POST,COCHIN,PIN : 4577 35 61.00 682021,682021 8 S08146 A L SUBHASHINI KURAPATI CONSULTANCY 10889 35 61.00 SERVICES,NR OLD P V R HIGH SCHOOL,COURL CENTRE ONGOLE PRAKESAM DIST,PIN : 523002,523002 Page : 2 Particulars of Unpaid Dividend declared by IFGL Refractories Limited for Financial Year 2006-07 as on 22nd Sepetmber,2014 Sl. -

Annual Report 2014 | I

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 | I ANNUAL REPORT 2014 II | ANNUAL REPORT 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The compilation of this Report would not have been possible without valuable inputs and hard work of officers of the Registry who have designed and compiled it. Information contributed by Director (Admn.) Chandigarh Judicial Academy, Member Secretaries, State Legal Services Authorities has immensely helped in giving shape to the report. Officials from Exclusive and Computer Cells devoted themselves wholeheartedly while collecting data from various quarters and branches and typesetting the same. We also acknowledge the contribution made by Sh. Jaskiran Singh, Office Executive, Chandigarh Judicial Academy, who took photographs which are part of the present Report. The name of Sh. Vikas Suri, Reporter ILR needs special mention who made strenuous efforts for compiling important judgments of this Court which have been included in the chapter - March of Law. Having acknowledged the valuable contributions in preparation of this Annual Report, we deem it our duty to own responsibility for any mistake, error or omission. Editorial Board: Justice M. Jeyapaul Justice Harinder Singh Sidhu Justice Lisa Gill Justice Dr. Shekhar Dhawan Designed & Compiled by: Sh. Parmod Goyal, Registrar (Computerization) Sh. Shatin Goyal, OSD (Rules & Protocol) Sh. Ravdeep Singh Hundal, OSD (Gaz. II) ANNUAL REPORT 2014 | III PUBLISHED BY High Court of Punjab and Haryana IV | ANNUAL REPORT 2014 VISION & MISSION To uphold the rule of law and constitutional values. To establish an effective and efficient judicial system in the States of Punjab, Haryana & U.T. Chandigarh. To enhance public trust and confidence in judicial system. To provide expeditious and cost effective redressal of legal rights to the satisfaction of litigant. -

VOLUME I ISSUE III Published by Harbinger

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LAW & MANAGEMENT STUDIES ISSN-2455-2771 | Indexed in IIJF, ROAD, SIS | Impact Factor: 2.145 (IIJF) VOLUME I ISSUE III JUNE 2016 Published by Harbinger INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LAW & MANAGEMENT STUDIES (ISSN-2455-2771) VOLUME I ISSUE III | Indexed in ROAD & Scholarly Open Access STUDENT EDITORIAL BOARD 1. Sameer Avasarala, Editor-in-Chief 2. Samiya Zehra, Advisor 3. Shashank Kanoongo, Head, Law Wing 4. Nitesh Krishna, Head, Management Wing 5. Sanjeet Choudhary, Associate Editor 6. Aishwarya Dhakarey, Editor 7. Pranahita Srinivas, Editor 8. Sumedha Sen, Editor 9. Mohit Kumar Gupta, Editor ADVISORY BOARD 1. Adv. Anantha Krishna, High Court of Hyderabad 2. Adv. Shravanth Arya Tandra, Karnataka High Court 3. Dr. Dhiraj Jain, SCMS, Pune 4. Dr. Lokanath Suar, G M Law College, Puri 5. Dr. Sudeepta Pradhan, ICFAI Business School, Hyderabad 6. Prof. Sharmila Devi, SCMS Pune 7. Dr. Monika Jain, Amity Law School, Delhi ii INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LAW & MANAGEMENT STUDIES (ISSN-2455-2771) VOLUME I ISSUE III | Indexed in ROAD & Scholarly Open Access “If India ever finds its way back to the freedom and democracy that were proud hallmarks of its first eighteen years as an independent nation, someone will surely erect a monument to Justice H R Khanna of the Supreme Court.” THE NEW YORK TIMES ON JUSTICE KHANNA This issue is dedicated to one of the best jurists India has ever known Justice Hans Raj Khanna (1912-2008) A Tribute to the Democratic Spirit in India Justice Khanna, known for his judgments that form the basis of the modern Constitutional Law in India, accredited with the formulation of the Basic Structure in Kesavananda Bharti’s case and for upholding the principles of Liberty and Democracy in the darkest hours of Indian Democracy during the Indian Emergency Era. -

Lok Sabha Debates

Tuesday, April 18, 1978 Chaitra 28, 1900 (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES ( S i x t h Scrim) V o L x m ( A p r i l 5 (919, i 97S C h * l t r « 15 t o 1) , i f M I M >)1 Foarth Scttlo*, iyrB/rtfj i f (Pa/. */// cwurinfNtt. 31 —40) LOE SABHA SECRETARIAT N E W D E L H I CONTENTS N o. 39, Tuesday, A pril 18, 1978fChcdtra 28, 1900 {SAKA) Oral Answers to Question.’ . C o l u m n s •Starred Questions Nos. 760 to 765,768 and 769* 1—32 'Written Answersto Questions: Starred Questions Nos. 766, 767, 770 to 774 and 776 to 779- 32— 44 Unstarred Questions Nos. 7131 to 7266 and 7268 to 7319 * 44— 240 Papers laid on the Table . 240—41 Re. Calling Attention 241— 42 Public Accounts Committee— Seventy-third Report presented 242 Committee on Public Undertakings — Fourth Report and Minutes presented 242— 43 Committee on Private Members’ Bills and Resolutions— Sventecnth Report presented 243 Committee on Petitions— Third Report presented....................................................................243 Matters under Rule 377— (i) Reported Withdrawal o f Consent by Chief Minister o f Karnataka to the exercise o f powers by C.B.I. in the State Shri Kanwar Lai G u p t a ............................................................. 243—45 **(ii) Reported Delay in Supply of Enriched Uranium by U.S.A. for Atomic Power Plant at Tarapur Shri Hari Vishnu K a m a t h .................................................245— 46 (iii) Reported Drought Conditions ir. Manipur Shri N. Tombi Singh 246 (iv) Reported Threat to resort to strike by officers of nationalised banks Shri Vinodbhai B. -

List of Advocates-On-Record (As on 25.09.2019)

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA (Record Room) List of Advocates-on-Record (as on 25.09.2019) Sl. No. Name & Address Date of File No./ Remarks CC. Code registration Reg.No. as an AOR 1 Sh A D Sikri (Advocate) 15/10/1981 690 34 A-102 Sahadara Colony, Sarai Rohilla, New Delhi 2 Sh A K Dhar (Advocate) 11/1/1984 769 42 No. 1, Doctor's Lane, New Delhi 3 Sh A K Ghose (Attorney) 6/8/1984 784 Attorney 47 1, Doctor's Lane, New Delhi 4 Sh A K Mandal (Attorney) 11/1/1984 770 Attorney 43 No. 1, Doctor's Lane, New Delhi 5 Sh A K Nag (Advocate) 7/8/1961 262 21, Lawyers Chambers, Supreme Court, New Delhi 6 Sh A K Panda (Advocate) 15/10/1981 689 Designated as Sr. Advocate 60, National Park, Lajpat Nagar IV, New Delhi w.e.f. 20/4/98 7 Sh A K Sanghi (Advocate) 20/3/1974 507 Designated as Sr. Advocate 22 B-122, Pandara Road, New Delhi we.f. 18.2.2010 8 Sh A L Trehan (Advocate) 1/5/1975 540 24 A-3/71, Sector V, Rohini, Delhi-85 9 Sh A Mariarputham (Advocate) 29/10/1984 791 Designated as Sr. Advocate 48 34/22, East Patel Nagar, New Delhi w.e.f. 16.10.08 :: 1 :: Sl. No. Name & Address Date of File No./ Remarks CC. Code registration Reg.No. as an AOR 10 Sh A N Arora (Advocate) 3/2/1954 58 1 90/G, Connaught Circus, New Delhi 11 Sh A N Khanna (Advocate) 27/1/1954 11 Removed on his own request M 27, Gokul Niwas, Connaught Circus, Opp. -

SUPREME COURT of INDIA Page 1 of 11 PETITIONER: RAMESHWAR DAYAL

http://JUDIS.NIC.IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 1 of 11 PETITIONER: RAMESHWAR DAYAL Vs. RESPONDENT: THE STATE OF PUNJAB AND OTHERS DATE OF JUDGMENT: 05/12/1960 BENCH: DAS, S.K. BENCH: DAS, S.K. SINHA, BHUVNESHWAR P.(CJ) GUPTA, K.C. DAS AYYANGAR, N. RAJAGOPALA MUDHOLKAR, J.R. CITATION: 1961 AIR 816 1961 SCR (2) 874 CITATOR INFO : D 1966 SC1987 (17) D 1985 SC 308 (2,3) ACT: District Judges--Eligibility for appointment--Appointment under the Constitution--Qualifications--Period of Practice as Advocate, if includes Period of practice in Lahore High Court---High Courts (Punjab) Order,1947, cl. 6--Bar Councils Act, 1926 (38 of 1926), s. 8--Constitution of India, Art. 233(2). HEADNOTE: The validity of the appointment of respondents 2 to 6 as District judges was challenged in a petition filed by the appellant under Art. 226 of the Constitution of India before the High Court of Punjab, on the ground, inter alia, that the appointment was made in contravention of Art. 233(2) of the Constitution of India which lays down that "a person not already in the service of the Union or of the State shall only be eligible to be appointed a district judge if he has been for not less than seven years an advocate or a pleader..." The respondents had been enrolled as advocates of the Lahore High Court on various dates between 1933 and 1940, and while respondents 2, 4 and 5 had their names on the roll of advocates of the Punjab High Court and were practising as advocates at the time they were appointed as District Judges in 1950 and 1952, respondents 3 and 6 did not have their names factually on the roll when they were appointed as District judges in 1957 and 1958. -

Last Six Months Important Current Affairs for SSC CGL Tier-I Exam 2017

GK Update PDF Last Six Months Important Current Affairs for SSC CGL Tier-I Exam 2017 sscadda.com /2017/08/last-six-months-current-affairs-for-ssc-cgl-tier1.html Dear Students, SSC CGL Exam 2017 Tier-I is going on. In GA section so many questions are being asked from current affairs. So, We've compiled "CURRENT AFFAIRS" of last Six months. These notes will help you in GS/GK section a lot. We wish you all the very best for your exam. 1.World Student Day: October 15 October 15th, Dr. Abdul Kalam's birthday is observed as The World Student Day by United Nations Organization annually. 2.International Day of the Girl Child :11 October. 3.PM Narendra Modi inaugurates Shaurya Smarak in Bhopal. 4.C Radhakrishnan selected for Mathrubhumi Literary award. 5.PM Narendra Modi announces India's first Railway University in Vadodara. 6.President, PM launch Hamid Ansari’s book titled "Citizen and Society" 1/5 7.Aviation scheme UDAN(Ude Desh Ka Aam Naagrik) takes off with the objective of "Let the common citizen of the country fly", aimed at making air travel affordable and widespread. 8.PM Narendra Modi launches 'Saur Sujala Yojana' in Chhattisgarh that would provide solar powered irrigation pumps to farmers at a subsidized price. 9.National Ayurveda Day being observed on 28-10-2016 on Prevention and Control of Diabetes(Madhumeha) through Ayurveda in New Delhi. 10.Bollywood actor Ranveer Singh has been now named the first Indian ambassador for Switzerland Tourism.To promote Switzerland Tourism’s campaign for 2017 – “Nature wants you back!”.