LEGAL ENGLISH and COMMUNICATION SKILLS (BALLB Ist Sem Code:105) SYLLABUS: Unit-L: Comprehension and Composition A. Reading Comp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Affairs= 07-09-2020

CURRENT AFFAIRS= 07-09-2020 KESAVANANDA BHARATI Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed grief over the passing away of Kesavananda Bharati Ji. About: Kesavananda Bharati was the head seer of the Edneer Mutt in Kasaragod district of Kerala since 1961. He left his signature in one of the significant rulings of the Supreme Court when he challenged the Kerala land reforms legislation in 1970. The Kesavananda Bharati judgement, is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of India that outlined the basic structure doctrine of the Constitution. Justice Hans Raj Khanna asserted through the Basic Structure doctrine that the constitution possesses a basic structure of constitutional principles and values. The doctrine forms the basis of power of the Indian judiciary to review and override amendments to the Constitution of India enacted by the Indian parliament. MOPLAH REBELLION A report submitted to the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) in 2016 had recommended the removal of the Wagon Tragedy victims and Malabar Rebellion leaders Ali Musliyar and Variamkunnath Ahmad Haji, and Haji’s two brothers from a book on martyrs of India’s freedom struggle. CROSS & CLIMB 2019 1 About: The report sought the removal of names of 387 ‘Moplah rioters’ from the list of martyrs. The book, Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle 1857-1947, was released by Prime Minister Narendra Modi last week. The report describes Haji as the “notorious Moplah Riot leader” and a “hardcore criminal,” who “killed innumerable innocent Hindu men, women, and children during the 1921 Moplah Riot, and deposited their bodies in a well, locally known as Thoovoor Kinar”. -

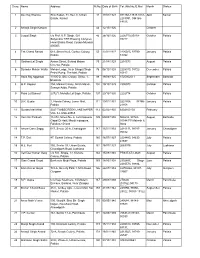

Directory of SBPROA Membership

Sr.no. Name Address M.No. Date of Birth Tel. /Mb.No./E.Mail Month Station 1 Dev Raj Sharma Shiv Sadan, 91, Sec. 6, Urban 17 17/04/1924 094168-14515 0184- April Karnal Estate, Karnal 2283091, 094168- 14515 2 Amarjit Singh Kanwar 44 12/10/1926 October 3 Jaspal Singh c/o Prof. K.P. Singh, 501 46 28/10/1926 2206719,95019- October Patiala Satyendra TIFR Housing Complex, 78227 Homi Bhaba Road, Colaba-Mumbai- 400005 4 Tek Chand Bansal 618, Street No.6, Gurbux Colony, 55 12/01/1927 2226025, 97790- January Patiala Patiala 18992 5 Girdhari Lal Singla Araian Street, Behind Malwa 75 21/08/1929 2201573 August Patiala Cinema, Patiala 6 Surinder Mohan Walia Mohan Lodge, Near Bhagat Singh 76 06/12/1928 2228310, 98722- December Patiala Petrol Pump, The Mall, Patiala 10817 7 Hans Raj Aggarwal 13305-D, Shiv Colony, St No. 1, 98 19/09/1925 8725902011 September Bathnda Bhatinda 8 O.P. Kapoor 204, Markal Colony, Mirch Mandi, 102 19/10/1929 2305070 October Patiala Sanauri Adda, Patiala 9 Piara Lal Bansal 2372/1, Mohalla Lal Bagh, Patiala 107 20/10/1930 2202714 October Patiala 10 D.R. Gupta 1, Narula Colony, Lower Mall, 111 10/01/1931 2221858. 98766- January Patiala Patiala 21858 11 Gurdas Mal Mittal 3347 TIMBECREEK LANE NAPER 112 02/02/1930 6304160102 February VILL ILL USA-60565 12 Hari Om Parkash 11/272, Street No. 6, Left Opposite 135 09/08/1930 500233, 98724- August Bathinda Gopal Di Hatti, Manjit Indarpura, 91544 PP Mahesh & Faridkot-151203 Sons 13 Ishwar Dass Saggu 647, Sector 20-A, Chandigarh 147 15/01/1933 2281111, 98787- January Chandigarh 70882 14 T.P. -

Parliamentary Documentation Vol. XXXVIII 1-15 July 2012 No.13

Parliamentary Documentation Vol. XXXVIII 1-15 July 2012 No.13 AGRICULTURE -(INDIA) 1 MAHAJAN, Ashwani Where's the action plan? DECCAN HERALD (BANGALORE), 2012(10.7.2012) Raises concern over the possible impact of poor monsoon on agriculture in India. ** Agriculture-(India). -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 2 Beware of the invasion. MONTHLY PUBLIC OPINION SURVEYS (NEW DELHI), V.57(No.9), 2012(Jun, 2012): P.8-9 Discusses the implications of cultivating genetically modified food crop in the country. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Research. 3 VENUGOPALAN, M V and Others Productivity and nitrogen-use efficiency yardsticks in conventional and Bt. Cotton hybrids on rainfed Vertisols. INDIAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES (NEW DELHI), V.82 (No.7), 2012(Jul, 2012): P.81-84 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Research. 4 VIJAYAN, V S Let's farm along with nature, not against it. TIMES OF INDIA (MUMBAI), 2012(15.7.2012) Highlights the recommendations made in the "M S Swaminathan Task Force Report on agricultural biodiversity". ** Agriculture-Agricultural Research. -AGRICULTURE POLICY-(INDIA-ASSAM) 5 DAS, Manmohan Revolution needed in agriculture. ASSAM TRIBUNE (GUWAHATI), 2012(4.7.2012) Emphasises the need to promote Agriculture Sector and rural industrialisation in Assam. ** Agriculture-Agriculture Policy-(India-Assam); Rural Industry. ** - Keywords 1 -FARMS AND FARMERS 6 DWAIPAYAN Small tea growers and Tea Board package. ASSAM TRIBUNE (GUWAHATI), 2012(1.7.2012) Expresses concern over plight of small tea growers in Assam. ** Agriculture-Farms and Farmers; Tea. 7 MISHRA, Alok K N Congress lends support to Nagri land fight. TIMES OF INDIA (MUMBAI), 2012(9.7.2012) Expresses concern over plight of the farmers living at Nagri village in Jharkhand. -

The Goncerned Federalists

THE GONCERNED FEDERALISTS Non-Prof t Assocration P O Box 2962 SOIVERSET WEST, 7129 27 February 2020 THE SPEAKER PARLIAMENT CAPE TOWN, 8OO1 OBJECTION TO THE CONSTITUTION AMENDMENT BILL Attached find hereto our objection to the proposed Constitution Amendment Billfor your attention. Kindly acknowledge receipt. We urgently await to hear your response. Yours faithfully Chairperson : R Smit Deputy Chairpeson :R W McCreath THE GONCERNED FEDERALISTS Submission to Parliament Be pleased to take notice that the Concerned Federalists herewith notes an objection to the proposed Amendment to Section 25 of the RSA Constitution Act 1 0B of 1996. 1. OUR AIMS AND OBJECTIVES The Concerned Federalists is a duly established non-profit association with the object to strengthen federalism and the rule of law in South Africa. 2, SECTION 25 As you are well aware, Section 25 provides that no one may be arbitrarily deprived of property and the property canot be expropriated without compensation. 3, THE CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES The lnterim Constituiion came into force on 27 April 1994 after a negotiated settlement was reached at CODESA. Various constitutional principles were adopted as a fundamental basis of a new Constitution to be certified by the Constitutional Court. Prominent Constitutional principles can be cited as follows: I The Constitution shall provide for a democratic system of government. ll Everyone shall enjoy all universally accepted fundamental rights, freedoms and civil liberties which shall be provided for and protected by entreated provisions in the Constitution. lll The Consiitution shall be supreme law of the land. -2- 4, UI,XIVERSAI-LY ACGEPTED FUI{DAMENTAL R]GHT'S, FREEDOMS AND CIVIL LIBERTIES The following international accepted agreements are herewith placed on record: a) The UN Charter (UNCH) b) The Universal Declaration of Human Righis (UDHR) '17(1) Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others (2) No one shalI be arbitrarily deprived of his property. -

Q1. Kesavananda Bharati Who Passed Away Recently Is a ___

Bankersadda.com Current Affairs Quiz for RBI Assistant Mains 2020 Adda247.com Quiz Date: 10th September 2020 Q1. Kesavananda Bharati who passed away recently is a ___________. (a) Choreographer (b) Spiritual Leader (c) Film Maker (d) Actor (e) Sand Artist Q2. Professor Govind Swarup who has passed away was famously known as ________ in India. (a) Father of Indian Organic Farming (b) Father of Indian Philosophy (c) Father of Indian Cinema (d) Father of Indian Radio Astronomy (e) Father of Indian Nationalism Q3. The Patrika Gate has been inaugurated in which city by PM Narendra Modi recently? (a) Jaipur (b) Bhopal (c) Agra (d) Delhi (e) Dehradun Q4. Jaya Prakash Reddy who has passed away recently was a well known actor of which film industry? (a) Tamil (b) Odia (c) Malayalam (d) Kannada (e) Telugu Q5. Who among the following has recently been conferred with the Indira Gandhi Peace Prize 2019? (a) Dinesh Bhugra (b) David Attenborough (c) Gabrielle Anwar (d) Upinder Randhawa (e) Jas Pal Singh Q6. Which of the following banks has launched the „Signature Visa Debit Card‟ for the affluent/high net worth individuals maintaining an average quarterly balance of Rs. 10 lakhs and above? (a) Canara Bank For any Banking/Insurance exam Assistance, Give a Missed call @ 01141183264 Bankersadda.com Current Affairs Quiz for RBI Assistant Mains 2020 Adda247.com (b) Bank of India (c) Bank of Baroda (d) ICICI (e) SBI Q7. Lawrencedale Agro Processing India (LEAF) has entered into an agreement with the Government of which state to expand the scope of food processing in the State? (a) Karnataka (b) Uttar Pradesh (c) Andhra Pradesh (d) Madhya Pradesh (e) Chhattisgarh Q8. -

KASARAGOD DISTRICT HAND BOOKS of KERALA D10844.Pdf

^ Sii B3S 310 KBR -J) DISTRICT HAND BOOKS OF KERALA KASARAGOD Di084i4 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC RFXATIONS, GOVERNtVfENT OF KERALA 32/165/97—1 KASARAGOD Department of Public Relations October 1997 N ati Plaoit Editor-in-chief 17*B, L. (t L. Natarajan I.A.S n rv -'v i* ’ T )-lh 5 ? U U Director of Public Relations 0 ^ ’ ^ ----- ' * Compiled by R. Ramachandran Dist. Information Officer, Kasaragod Editor M. Josephath (Information Officer, Planning & Development) Asst. Editor Xavier Primus Raj an M.R. (Asst. Infomiation Officcr, Planning & Development) Cover E. S. Varghese Published by the Director, Department of Public Relations, Government of Kerala. Copies : 10,000 Not for Sale Contents Introduction.................................................................................5 A Short History ......................................................................... 5 T opography..............................................................................7 C lim ate......................................................................................... 8 F o re s t........... ................................................................................8 R iv ers............................................................................................8 P o p u latio n ...................................................................................9 A dm in istratio n ...............................:......... .......................... 1 1 A griculture............................................................................... 15 -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

Annual Report 2007-2008

The Supreme Court of India The Supreme Court of India ANNUAL REPORT 2007-2008 (Published by the Supreme Court of India) EDITORIAL COMMITTEE: For Official use Only Hon’ble Mr. Justice S.B. Sinha Hon’ble Mr. Justice R.V. Raveendran COPYRIGHT© 2008 : THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Hon’ble Mr. Justice D.K. Jain Publisher : The Supreme Court of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be New Delhi-110001 reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted Website – http://supremecourtofindia.nic.in in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, Book : Annual Report 2007-2008 photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior (Contents mainly relate to 1.10.2007 to permission in writing of the copyright owner. 30-09.2008) Printed at I G Printers Pvt. Ltd. Tel. No: 011-26810297, 26817927 Photography: J.S. Studio (Sudeep Jain) 9810220385 (M) CONTENTS PAGE S. DESCRIPTION NO. NOS. 1. Hon’ble Chief Justice of India & Hon’ble Judges of Supreme Court ................................................................................. 9 2. An overview .......................................................................................... 39 The History Supreme Court – At present Court Building Lawyers’ Chambers Supreme Court Museum Retired Hon’ble Chief Justices Retired Hon’ble Judges 3. Jurisdiction .......................................................................................... 49 Original Appellate Advisory Review Curative Public Interest Litigation 4. The Bar ............................................................................................... -

Kesavananda Bharati V. State of Kerala By

LatestLaws.com CASE ANALYSIS: KESAVANANDA BHARATI V. STATE OF KERALA1 BY: AYUSHI MODI AND ROHAN UPADHYAY INTRODUCTION: The Kesavananda Bharati case was popularly known as fundamental rights case and also the serious conflict between the Judiciary and the Government. Under this case Supreme Court of India outlined the Basic Structure doctrine of the Constitution which forms and gives basic powers to the Indian Judiciary to review or to amend the provisions of the constitution enacted by the Parliament of India which conflict with or seek to alter the basic structure of the constitution. The fundamental question dealt in Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala is whether the power to amend the constitution is an unlimited, or there is identifiable parameters regarding powers to amend the constitution. HOLDING OF THE CASE: There are certain principles within the framework of Indian Constitution which are inviolable and hence cannot be amended by the Parliament. These principles were commonly termed as Basic Structure. BACKGROUND: Before moving to the facts and Judgment of the case one must know the background of the case: • The Bihar Land Reforms Act, 1950 which was in Contravention of then Fundamental Right to Property (Article 31). It was hit by 13(3) as it was Infringing Article 31 (Part III, Fundamental Rights). The Act was tested in High Court which held the demonstration to be Unconstitutional for being violative of Article 14 of the Constitution. • Consequently keeping in mind the end goal to ensure and Validate Zamindari Abolition laws, the Government made First Amendment of the 1 (1973) 4 SCC 225 LatestLaws.com Constitution of India which rolled out a few improvements to the Fundamental Rights arrangements of the Constitution. -

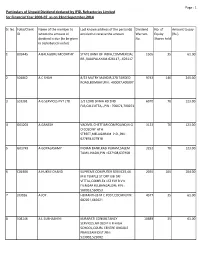

List of Unpaid and Or Unclaimed Dividend FY 2006-07

Page : 1 Particulars of Unpaid Dividend declared by IFGL Refractories Limited for Financial Year 2006-07 as on 22nd Sepetmber,2014 Sl. No. Folio/Client Name of the member to Last known address of the person(s) Dividend No. of Amount to pay ID whom the amount of entitled to receive the amount Warrant Equity (Rs.) dividend is due (to be given No. Shares held in alphabetical order) 1 B03445 A BALAGURU MOORTHY STATE BANK OF INDIA,COMMERCIAL 1505 35 61.00 BR.,RAJAPALAYAM-626117,-,626117 2 S01862 A C SHAH 8/23 MATRY MANDIR,278 TARDEO 9743 140 245.00 ROAD,BOMBAY,PIN : 400007,400007 3 L01301 A G SERVICES PVT LTD 1/2 LORD SINHA RD 2ND 6070 70 123.00 FLR,CALCUTTA,-,PIN : 700071,700071 4 G01203 A GANESH VADIVEL CHETTIAR COMPOUND,N G 3123 70 123.00 O COLONY 6TH STREET,MELAGARAM P.O.,PIN : 627818,627818 5 G01749 A GOPALASAMY INDIAN BANK,RASI PURAM,SALEM 3252 70 123.00 TAMIL NADU,PIN : 637408,637408 6 C01906 A HUKMI CHAND SUPREME COMPUTER SERVICES,44 2055 105 184.00 M K TEMPLE ST OPP UBI SRI VITTAL,COMPLEX 1ST FLR B V K IYENGAR RD,BANGALORE PIN : 560053,560053 7 J03026 A JOY HEMANTH,B M C POST,COCHIN,PIN : 4577 35 61.00 682021,682021 8 S08146 A L SUBHASHINI KURAPATI CONSULTANCY 10889 35 61.00 SERVICES,NR OLD P V R HIGH SCHOOL,COURL CENTRE ONGOLE PRAKESAM DIST,PIN : 523002,523002 Page : 2 Particulars of Unpaid Dividend declared by IFGL Refractories Limited for Financial Year 2006-07 as on 22nd Sepetmber,2014 Sl. -

Important SC Judgements for UPSC Kesavananda Bharati Case

Kesavananda Bharati Case - Important SC Judgements for UPSC Many Supreme Court judgements have changed the face of Indian polity and law. These landmark SC judgements are very important segments of the UPSC syllabus. In this series, we bring to you important SC judgments explained and dissected, for the benefit of IAS aspirants. In this article, you can read all about the Kesavananda Bharati case. Get a list of landmark SC judgements for the UPSC exam in the linked article. Kesavananda Bharati Case Case Summary - Kesavananda Bharati & Others (Petitioners) V State of Kerala (Respondents) Kesavananda Bharati & others Versus State of Kerala is certainly one of the leading cases in the constitutional history of India if not the most important judgement of post-independent India and is popularly known as the Fundamental Rights case. The majority judgement in the case was pronounced by S.M.Sikri C. J., Hegde J, Mukherjea J, Shehlat J, Grover J, Jaganmohan Reddy J, Khanna J, and was dissented by Ray J, Palekar J, Mathew J, Beg J, Dwivedi J and Chandrachud J. It is rightly said that the judgement in the instant case brought an end to the conflict between the executive and the judiciary and proved to be a saviour of the democratic system and set up in the country. The resultant judgement in the case was a hard-fought legal battle between the two constitutional stalwarts and legal luminaries namely N.A. Palkhivala (who represented Petitioners) and H.M. Seervai (who represented the State of Kerala). The hearing in the case took place for sixty-eight long days and finally, a voluminous 703-page judgement was pronounced on 24th April 1973. -

Gradeup 365 Polity and Governance Table of Contents

GradeUP 365 Polity and Governance Table of Contents 1. Constitutional Issues and Important Judgements 1.1. Kesavananda Bharati Case 1.2. Supreme Court judgment on right to protest 1.3. Contempt of Court 1.4. Sub categorisation of SCs and STs 1.5. Padmanabhaswamy Temple Case 1.6. Mirror Order 1.7. Inner Line Permit (ILP) 1.8. Sixth Schedule 2. Centre State Relations 2.1. 15th Finance Commission Recommendations 2.2. Power of the Governor to summon the Legislative Assembly 3. Working of the Legislature 3.1. Voting and Division of Votes in the Rajya Sabha 3.2. Suspension of Rajya Sabha MPs 3.3. Deputy Speaker of Lok Sabha 3.4. Question hour In Parliament 4. Important Legislations 4.1. Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Act, 2020 4.2. Maharashtra Shakti Bill, 2020 4.3. Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Ordinance, 2020 5. Elections 5.1. Elections to Rajya Sabha 5.2. Right to recall panchayat member 5.3. Voting Rights to Non Resident Indians (NRIs) 5.4. U.S. Electoral College 6. Institutions 6.1. General consent to CBI 6.2. Civil Services Board 7. Governance 7.1. Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2005 7.2. Mission Karmayogi 7.3. Non-Personal Data Governance Framework 7.4. National Recruitment Agency (NRA) 7.5. Committee for the Reform of Criminal Laws 7.6. e-Courts Project 7.7. Data Governance Quality Index 7.8. Public Affairs Index (PAI) 1. Constitutional Issues and Important Judgements 1.1. Kesavananda Bharati Case Context: Recently, Kesavananda Bharati the head seer of the Edneer Mutt in Kasaragod district of Kerala since 1961 died.