CCA] Inclusive For/Adapted to Everybody?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis and Optimization of a Dissolved Air Flotation Process for Separation of Suspended Solids in Wastewater

Analysis and optimization of a dissolved air flotation process for separation of suspended solids in wastewater Oskar Bäck Natural Resources Engineering, master's 2021 Luleå University of Technology Department of Civil, Environmental and Natural Resources Engineering Analysis and optimization of a dissolved air flotation process for separation of suspended solids in wastewater Oskar Bäck i Preface This report represents a master thesis within the master program in Natural resource engineering with focus on water and environmental science at Luleå University of Technology. The study was conducted in collaboration with Roslagsvatten AB, a Swedish water utility, about Margretelund wastewater treatment plant’s dissolved air flotation process. The study was held during a period of 20 weeks in the spring of 2021, corresponding to 30 ECTS. There are a lot of people I am thankful for helping me through this master thesis, and especially my supervisor at Luleå university of technology (LTU), Inga Herrmann, for helping me sort through all my ideas and thoughts and encourage me during these 20 weeks. I wish to both congratulate and thank my fellow classmates from LTU, and all the discussions we have had together, through both high and lows. I would also like to direct a special thank you to my supervisor from Roslagsvatten, Daniel Zetterström, for helping me with everything and anything on-site during the thesis and always came with a good answer no matter the question. Thank you, Annelie Hedström, for helping me bring out the most from this thesis as examiner. I am thankful for the opportunity given to work on this master thesis together with the process division at Roslagsvatten, and for all the help and support given by everyone at Margretelund wastewater treatment plant. -

Annual Report 2010 Report Annual Svevia Content

Svevia Annual Report 2010 Content Svevia in figures 1 Comments from the CEO 2 Vision, goals and strategies 4 Business world and the market 6 Annual Report 2010 Core operation — road management 8 and maintenance Core operation — civil engineering 10 Strategic specialty operations 12 Organisation 14 Control for higher profitability 16 Svevia’s sustainability report 18 Corporate Governance Report 32 Board of Directors and management 36 Financial reports 38 Administration report 39 More information about Svevia 80 Own path Svevia Box 4018 SE-171 04 Solna Sweden www.svevia.se Svevia Annual Report 2010 Contents Svevia in figures 1 Comments from the CEO 2 Vision, goals and strategies 4 Business world and the market 6 Annual Report 2010 Core operation — road management 8 and maintenance Core operation — civil engineering 10 Strategic specialty operations 12 Organisation 14 Control for higher profitability 16 Svevia’s sustainability report 18 Corporate Governance Report 32 Board of Directors and management 36 Financial reports 38 Administration report 39 More information about Svevia 80 Own path Svevia Box 4018 SE-171 04 Solna Sweden www.svevia.se This is Svevia Leading in infrastructure Addresses Solna Head office Regional Office, Central Svevia Box 4018 SE-171 04 Solna Visit address: Hemvärnsgatan 15 Tel: +46 (0(8-404 10 00 Fax: +46 (0(8-404 10 50 Own path Reliability and consideration Attractive workplace Svevia is a company that has chosen its own Svevia is the reliable and considerate contrac- Svevia aims to be an exemplary employer Umeå path. We focus on building and maintaining ting company that dares to be innovative. -

Operational Programme Under the 'Investment For

OPERATIONAL PROGRAMME UNDER THE ‘INVESTMENT FOR GROWTH AND JOBS’ GOAL CCI 2014SE16RFOP005 Title Stockholm Version 1.3 First year 2014 Last year 2020 Eligible from 01-Jan-2014 Eligible until 31-Dec-2023 EC decision number C(2014)9970 EC decision date 16-Dec-2014 MS amending decision number MS amending decision date MS amending decision entry into force date NUTS regions covered by SE110 — Stockholm County the operational programme EN EN EN 1. STRATEGY FOR THE OPERATIONAL PROGRAMME’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE UNION STRATEGY FOR SMART, SUSTAINABLE AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH AND THE ACHIEVEMENT OF ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND TERRITORIAL COHESION 1.1 Strategy for the operational programme’s contribution to the Union strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and to the achievement of economic, social and territorial cohesion 1.1.1 Description of the programme’s strategy for contributing to the delivery of the Union strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and for achieving economic, social and territorial cohesion. The regional Structural Funds programme covers Stockholm County, which coincides with the geographical area of Stockholm in the European Union’s NUTS2 classification. Today, in 2013, the region has a population of just over 2.1 million, divided between 26 municipalities. The largest municipality, Stockholm City, in addition to being the national capital, is the largest municipality in the region (and in Sweden), with nearly 900 000 inhabitants. The smallest municipalities in the county, by comparison, have a population of around 10 000. The annual increase in population during the programming period 2007-2013 was just over 35 000. -

Facts About Botkyrka –Context, Character and Demographics (C4i) Förstudie Om Lokalt Unesco-Centrum Med Nationell Bäring Och Brett Partnerskap

Facts about Botkyrka –context, character and demographics (C4i) Förstudie om lokalt Unesco-centrum med nationell bäring och brett partnerskap Post Botkyrka kommun, 147 85 TUMBA | Besök Munkhättevägen 45 | Tel 08-530 610 00 | www.botkyrka.se | Org.nr 212000-2882 | Bankgiro 624-1061 BOTKYRKA KOMMUN Facts about Botkyrka C4i 2 [11] Kommunledningsförvaltningen 2014-05-14 The Botkyrka context and character In 2010, Botkyrka adopted the intercultural strategy – Strategy for an intercultural Botkyrka, with the purpose to create social equality, to open up the life chances of our inhabitants, to combat discrimination, to increase the representation of ethnic and religious minorities at all levels of the municipal organisation, and to increase social cohesion in a sharply segregated municipality (between northern and southern Botkyrka, and between Botkyrka and other municipalities1). At the moment of writing, the strategy, targeted towards both the majority and the minority populations, is on the verge of becoming implemented within all the municipal administrations and the whole municipal system of governance, so it is still to tell how much it will influence and change the current situation in the municipality. Population and demographics Botkyrka is a municipality with many faces. We are the most diverse municipality in Sweden. Between 2010 and 2012 the proportion of inhabitants with a foreign background increased to 55 % overall, and to 65 % among all children and youngsters (aged 0–18 years) in the municipality.2 55 % have origin in some other country (one self or two parents born abroad) and Botkyrka is the third youngest population among all Swedish municipalities.3 Botkyrka has always been a traditionally working-class lower middle-class municipality, but the inflow of inhabitants from different parts of the world during half a decade, makes this fact a little more complex. -

Barriers in Municipal Climate Change Adaptation

Futures 49 (2013) 9–21 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Futures jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/futures Barriers in municipal climate change adaptation: Results from case studies using backcasting Annika Carlsson-Kanyama *, Henrik Carlsen, Karl-Henrik Dreborg FOI, Sweden A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: An experimental case study approach using backcasting methodology with the Available online 21 March 2013 involvement of stakeholders was applied to develop visions of two ideally climate- adapted Swedish municipalities 20–30 years ahead in time. The five visions created were examined as regards measures that decision makers at other levels in society need to take in order to make local adaptation possible. Dependencies on other levels in society are strong regarding supply of water and treatment of sewage, energy supply and cooling, the built environment and care for the elderly, showing the strong integration of organisations at various levels in Swedish society. Barriers to adaptation relate not only to how global companies, government agencies and regional authorities act, but also to the degree of privatisation in municipalities, where poor skills in public procurement pose a barrier to adaptation. ß 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Background and aim of the study Adaptation to climate change on the local level is a new challenge that will call for considerable efforts by many municipal authorities [1]. When planning for the next 20–30 years, measures to cope with more extreme weather events such as heatwaves, intense precipitation and rising sea levels are of special importance as regards securing provision of services such as drinking water, sanitation, energy, care and education [2]. -

Utjämningsskatten Och Dess Effekter På Investeringsutgiften

Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för Samhällsvetenskaper Masteruppsats 15 hp | Företagsekonomi | Vårtermin 2013 Utjämningsskatten och dess effekter på investeringsutgiften. – Fallet Danderyds Kommun Av: Veronika Ulasevich Handledare: Besrat Tesfaye, Karl Gratzer Innehållsförteckning 1. Introduktion ......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Inledning ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Bakgrund .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Historik och fakta .................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4. Problemformulering ............................................................................................................................................. 10 1.5. Syfte .......................................................................................................................................................................... 10 2. Metod ................................................................................................................................................................................. 11 2.1. -

Read Full Report (PDF)

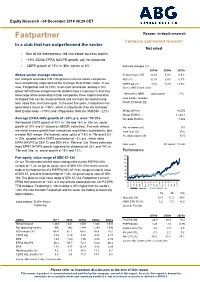

Equity Research - 04 December 2019 06:29 CET Fastpartner Reason: In-depth research Company sponsored research In a club that has outperformed the sector Not rated One of the entrepreneur-led real estate success stories ~19% 2020e EPRA NAVPS growth, adj. for dividends CEPS growth of 15% in ‘20e, sector at 6% Estimate changes (%) 2019e 2020e 2021e Above-sector average returns Rental income RE (%) 0.9% 5.9% 6.5% Our analysis concludes that entrepreneur-led real estate companies NOI (%) -0.1% 5.9% 6.7% have consistently outperformed the Carnegie Real Estate Index. In our CEPS adj (%) 3.7% 8.3% 11.5% view, Fastpartner and its CEO, Sven-Olof Johansson, belong in this Source: ABG Sundal Collier group. What these entrepreneurial leaders have in common is that they Share price (SEK) 02/12/2019 91.6 have large share ownership in their companies, have capital allocation strategies that can be unconventional and are more focused on long- Real Estate, Sweden term value than short-term gain. In the past five years, Fastpartner has FPAR.ST/FPAR SS generated a return of ~190%, which is 20pp better than the Carnegie Real Estate Index ~170%) and 170pp better than the OMXS30 ~22%). MCap (SEKm) 16,570 MCap (EURm) 1,568.7 Average EPRA NAV growth of ~20% p.a. over ’19-’21e Net debt (EURm) 1,269 We forecast CEPS growth of 17% in ’19e and 15% in ’20e (vs. sector growth of 10% and 6% based on ABGSC estimates). The main drivers No. of shares (m) 181 are rental income growth from announced acquisitions and projects, plus Free float (%) 30.0 a higher NOI margin. -

Mobilising Digitalisation to Serve Environmental Goals

kth royal institute of technology Doctoral Thesis in Planning and Decision Analysis Mobilising digitalisation to serve environmental goals TINA RINGENSON Stockholm, Sweden 2021 Mobilising digitalisation to serve environmental goals TINA RINGENSON Academic Dissertation which, with due permission of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, is submitted for public defence for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy on Thursday the 28th of January 2021, at 1:00 PM in U1, Brinellvägen 28A, Stockholm and virtually on Zoom. Doctoral Thesis in Planning and Decision Analysis with Specialisation in Environmental Strategic Analysis KTH Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm, Sweden 2021 © Tina Ringenson © Mattias Höjer, Anna Kramers, Anna Viggedal, Peter Arnfalk, Liridona Sopjani, Martin Sjöman Cover page photo: Tina Ringenson ISBN: 978-91-7873-737-6 TRITA-ABE-DLT-2044 Printed by: Universitetsservice US-AB, Sweden 2020 Abstract Human development is currently leading to destruction of the stability of the earth system upon which we depend for our survival. In other words, it is unsustainable. At the same time, urbanisation and digitalisation are progressing at a rapid pace. Digital technologies have a potential to decrease environmental impact from cities and urban lifestyles. Transport and mobility is an important part of urban life, and it has been suggested that digital technology can improve urban transport performance in both accessibility and sustainability. Mobility as a Service (MaaS) is a relatively new concept for provision of mobility services through a digital platform, sometimes together with digital accessibility services that lower the need to travel (Accessibility as a Service – AaaS). It has been suggested that MaaS could offer a real alternative to the privately owned car and lead to more sustainable mobility. -

Futures Beyond GDP Growth

Futures Beyond GDP Growth Final report from the research program 'Beyond GDP Growth: Scenarios for sustainable building and planning' Beyond GDP-growth Scenarios for sustainable building and planning Pernilla Hagbert, Göran Finnveden, Paul Fuehrer, Åsa Svenfelt, Eva Alfredsson, Åsa Aretun, Karin Bradley, Åsa Callmer, Eléonore Fauré, Ulrika Gunnarsson-Östling, Marie Hedberg, Alf Hornborg, Karolina Isaksson, Mikael Malmaeus, Tove Malmqvist, Åsa Nyblom, Kristian Skånberg and Erika Öhlund Futures Beyond GDP Growth Final report from the research program 'Beyond GDP Growth: Scenarios for sustainable building and planning' This is a translation of the Swedish report 'Framtider bortom BNP- tillväxt: Slutrapport från forskningsprogrammet ’Bortom BNP-tillväxt: Scenarier för hållbart samhällsbyggande' KTH School of Architecture and the Built Environment, 2019 TRITA-ABE-RPT-1835 ISBN: 978-91-7873-044-5 Illustrations: Sara Granér Printed by: Elanders Sverige AB, Vällingby Preface This report was produced as part of the research program 'Beyond GDP Growth: Scenarios for sustainable building and planning' (www.bortombnptillvaxt.se), which is a strong research environment funded by the Swedish Research Council Formas. The research program ran from spring 2014 to fall 2018. The project has brought together many researchers from diferent disciplines, organized into diferent work packages. The following researchers have participated in the research program: professor Göran Finnveden (KTH), project manager and director of the Sustainability Assessment work -

LIVSMEDELSVERKETS SAMARBETSRAPPORT S 2020 Nr 01

LIVSMEDELSVERKETS SAMARBETSRAPPORT S 2020 nr 01 Contaminants in blood and urine from adolescents in Sweden Results from the national dietary survey Riksmaten Adolescents 2016–17 _________________ Denna titel kan laddas ner från: Livsmedelsverkets webbsida för att beställa eller ladda ner material. Citera gärna Livsmedelsverkets texter, men glöm inte att uppge källan. Bilder, fotografier och illustrationer är skyddade av upphovsrätten. Det innebär att du måste ha upphovsmannens tillstånd att använda dem. © Livsmedelsverket, 2020. Författare: Livsmedelsverket, Naturvårdsverket. Rekommenderad citering: Livsmedelsverket, Naturvårdsverket. S 2020 nr 01: Contaminants in blood and urine from adolescents in Sweden. Livsmedelsverkets samarbetsrapport. Uppsala. S 2020 nr 01 ISSN 1104-7089 Omslag: Livsmedelsverket Preface The present report summarises the results from analysis of contaminants in blood and urine samples from participants in the dietary survey Riksmaten Adolescents 2016–17. These biomonitoring data provide unique information on total exposure to contaminants from all sources, including food, in Swedish adolescents. The results will be used further in risk assessments of contaminants in food by the Swedish Food Agency (Livsmedelsverket). Data from the project is also part of the national health-related environmental monitoring at the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket). The aim of this monitoring is to estimate human exposure to hazardous substances, follow temporal trends in human exposure, and to link environmental exposure to effects on health. The results from this report may also be useful for experts working with risk assessment and risk management in other organizations at the national or regional level. The dietary survey Riksmaten Adolescents 2016–17 was carried out by the Swedish Food Agency. The analysis of contaminants and the writing of this report were mainly financed by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (agreement numbers 2215-17-007, 2215-17-017 and 2215-18-010) and by the Swedish Food Agency. -

![“Yoake [夜明け]” a Gunslinger Girl Original Story by Kiskaloo](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3339/yoake-a-gunslinger-girl-original-story-by-kiskaloo-1063339.webp)

“Yoake [夜明け]” a Gunslinger Girl Original Story by Kiskaloo

This story uses characters and locations based on the Gunslinger Girl manga written by Yu Aida and published in monthly shōnen magazine Dengeki Daioh. The characters of Kara and Michele are original to myself. “Yoake [夜明け]” A Gunslinger Girl Original Story by Kiskaloo “Heaven is not enough…if when I am there I don’t remember you.” – Yoko Kanno. On a warm March Wednesday, in the passenger seat of a Lamborghini Gallardo Spyder parked on the side of the Autostrada 24 in a suburb east of Rome, Fleda Claes Johansson started to cry, her sobs drowned out by the flow of late afternoon traffic though Michele could see her chest heave and see the tears stream down her face. He removed a clean handkerchief from his pants pocket and handed it to Claes, who turned towards him with eyes red from tears and cheeks red from embarrassment. “Gratzie,” she said as she dabbed at her eyes and wiped her cheeks. She sniffled with a sharp intake of breath through her nose and her face set in a hard look, only a moment later to collapse into a fresh bout of crying. She buried her face in the handkerchief and willed herself into composure. “Crying like a schoolgirl rejected by her crush,” she said, her tone harsh. “You were conditioned to love him. And now that you remember him, it’s natural to miss him knowing that’s he is gone,” Michele offered. “What we shared wasn’t really love,” Claes noted. “I mean I did love him because the conditioning made me, but it made him uncomfortable.” She took in a few deep breaths to steady herself. -

To Reuse Or to Incinerate?

To Reuse or to Incinerate? A case study of the environmental impacts of two alternative waste management strategies for household textile waste in nine municipalities in northern Stockholm, Sweden Robert Bodin, MSc candidate Master of Science Thesis Stockholm 2016 Abstract With an increasing human population in the world, textiles are part of current unsustainable consumption patterns. Unlike most other mass produced products available today however, textiles are often vital to satisfy human core needs, and cannot be considered superfluous. Textile materials can be problematic from an environmental perspective. Synthetics are made from non-renewable petroleum, while production natural textile materials are very resource intensive, and rely on non-renewable energy supplies. Many reports on textiles indicate that production and use have great environmental impacts compared to waste management. On the other hand, it is in the latter phase decided whether the textile should be reused, recycled or discarded. These different material flow alternatives greatly determine overall impacts, since the possibility of avoided production through reuse and recycling is an important factor to consider. The main goal of this report was, through the use of life cycle assessment (LCA), to evaluate the environmental impact of household textile waste management from reuse and disposal alternatives, when conducted through the activities of the Swedish waste management company SÖRAB. Two different waste management strategies/scenarios where compared: one centered around incineration of textile waste, specified as the incineration scenario, and one focused on a textile waste flow where the textiles are separated from household waste and sorted for reuse, recycling and incineration, specified as the reuse scenario.