Defining Go Modules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freebsd-And-Git.Pdf

FreeBSD and Git Ed Maste - FreeBSD Vendor Summit 2018 Purpose ● History and Context - ensure we’re starting from the same reference ● Identify next steps for more effective use / integration with Git / GitHub ● Understand what needs to be resolved for any future decision on Git as the primary repository Version control history ● CVS ○ 1993-2012 ● Subversion ○ src/ May 31 2008, r179447 ○ doc/www May 19, 2012 r38821 ○ ports July 14, 2012 r300894 ● Perforce ○ 2001-2018 ● Hg Mirror ● Git Mirror ○ 2011- Subversion Repositories svnsync repo svn Subversion & Git Repositories today svn2git git push svnsync git svn repo svn git github Repositories Today fork repo / Freebsd Downstream svn github github Repositories Today fork repo / Freebsd Downstream svn github github “Git is not a Version Control System” phk@ missive, reproduced at https://blog.feld.me/posts/2018/01/git-is-not-revision-control/ Subversion vs. Git: Myths and Facts https://svnvsgit.com/ “Git has a number of advantages in the popularity race, none of which are really to do with the technology” https://chapmanworld.com/2018/08/25/why-im-now-using-both-git-and-subversion-for-one-project/ 10 things I hate about Git https://stevebennett.me/2012/02/24/10-things-i-hate-about-git Git popularity Nobody uses Subversion anymore False. A myth. Despite all the marketing buzz related to Git, such notable open source projects as FreeBSD and LLVM continue to use Subversion as the main version control system. About 47% of other open source projects use Subversion too (while only 38% are on Git). (2016) https://svnvsgit.com/ Git popularity (2018) Git UI/UX Yes, it’s a mess. -

Common Tools for Team Collaboration Problem: Working with a Team (Especially Remotely) Can Be Difficult

Common Tools for Team Collaboration Problem: Working with a team (especially remotely) can be difficult. ▹ Team members might have a different idea for the project ▹ Two or more team members could end up doing the same work ▹ Or a few team members have nothing to do Solutions: A combination of few tools. ▹ Communication channels ▹ Wikis ▹ Task manager ▹ Version Control ■ We’ll be going in depth with this one! Important! The tools are only as good as your team uses them. Make sure all of your team members agree on what tools to use, and train them thoroughly! Communication Channels Purpose: Communication channels provide a way to have team members remotely communicate with one another. Ideally, the channel will attempt to emulate, as closely as possible, what communication would be like if all of your team members were in the same office. Wait, why not email? ▹ No voice support ■ Text alone is not a sufficient form of communication ▹ Too slow, no obvious support for notifications ▹ Lack of flexibility in grouping people Tools: ▹ Discord ■ discordapp.com ▹ Slack ■ slack.com ▹ Riot.im ■ about.riot.im Discord: Originally used for voice-chat for gaming, Discord provides: ▹ Voice & video conferencing ▹ Text communication, separated by channels ▹ File-sharing ▹ Private communications ▹ A mobile, web, and desktop app Slack: A business-oriented text communication that also supports: ▹ Everything Discord does, plus... ▹ Threaded conversations Riot.im: A self-hosted, open-source alternative to Slack Wikis Purpose: Professionally used as a collaborative game design document, a wiki is a synchronized documentation tool that retains a thorough history of changes that occured on each page. -

CSE Student Newsletter

CSE Student Newsletter August 26, 2021 – Volume 11, Issue 18 Computer Science and Engineering University of South Florida Tampa, Florida http://www.cse.usf.edu Dear CSE Students: Welcome to the first newsletter of the Fall 2021 semester. Message from the UG Advisor: Add/drop week ends on 8/27. Schedules need to be final by 5:00PM on August 27. Students are responsible for the tuition and fees for any classes they are registered for after add/drop, even if they drop them later. August 27- TUITION PAYMENTS DUE to avoid late fees and cancellation of registration for non-payment. Tuition waiver forms are due to me for students appointed as TA/RA. September 20 - Deadline to apply for graduation in OASIS and send me your paperwork. October 8 - Tuition payments due for graduate assistants with tuition waivers, students with billed Florida prepaid tuition plans or with financial aid deferments to avoid $100 late payment fee. Please see the attached emails for more information. Message from the Grad Program Assistant: Add/drop week ends on 8/27. Schedules need to be final by 5:00PM on August 27. Students are responsible for the tuition and fees for any classes they are registered for after add/drop, even if they drop them later. August 27- TUITION PAYMENTS DUE to avoid late fees and cancellation of registration for non-payment. Tuition waiver forms are due to me for students appointed as TA/RA. September 20 - Deadline to apply for graduation in OASIS and send me your paperwork. October 8 - Tuition payments due for graduate assistants with tuition waivers, students with billed Florida prepaid tuition plans or with financial aid deferments to avoid $100 late payment fee. -

Letter, If Not the Spirit, of One Or the Other Definition

Producing Open Source Software How to Run a Successful Free Software Project Karl Fogel Producing Open Source Software: How to Run a Successful Free Software Project by Karl Fogel Copyright © 2005-2021 Karl Fogel, under the CreativeCommons Attribution-ShareAlike (4.0) license. Version: 2.3214 Home site: https://producingoss.com/ Dedication This book is dedicated to two dear friends without whom it would not have been possible: Karen Under- hill and Jim Blandy. i Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................. vi Why Write This Book? ............................................................................................... vi Who Should Read This Book? ..................................................................................... vi Sources ................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... viii For the first edition (2005) ................................................................................ viii For the second edition (2021) .............................................................................. ix Disclaimer .............................................................................................................. xiii 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

Protecting the Crown: a Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park

Protecting the Crown A Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement H2380040001 (WASO) RM-CESU Task Agreement J1434080053 Theodore Catton, Principal Investigator University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Diane Krahe, Researcher University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Deirdre K. Shaw NPS Key Official and Curator Glacier National Park West Glacier, Montana 59936 June 2011 Table of Contents List of Maps and Photographs v Introduction: Protecting the Crown 1 Chapter 1: A Homeland and a Frontier 5 Chapter 2: A Reservoir of Nature 23 Chapter 3: A Complete Sanctuary 57 Chapter 4: A Vignette of Primitive America 103 Chapter 5: A Sustainable Ecosystem 179 Conclusion: Preserving Different Natures 245 Bibliography 249 Index 261 List of Maps and Photographs MAPS Glacier National Park 22 Threats to Glacier National Park 168 PHOTOGRAPHS Cover - hikers going to Grinnell Glacier, 1930s, HPC 001581 Introduction – Three buses on Going-to-the-Sun Road, 1937, GNPA 11829 1 1.1 Two Cultural Legacies – McDonald family, GNPA 64 5 1.2 Indian Use and Occupancy – unidentified couple by lake, GNPA 24 7 1.3 Scientific Exploration – George B. Grinnell, Web 12 1.4 New Forms of Resource Use – group with stringer of fish, GNPA 551 14 2.1 A Foundation in Law – ranger at check station, GNPA 2874 23 2.2 An Emphasis on Law Enforcement – two park employees on hotel porch, 1915 HPC 001037 25 2.3 Stocking the Park – men with dead mountain lions, GNPA 9199 31 2.4 Balancing Preservation and Use – road-building contractors, 1924, GNPA 304 40 2.5 Forest Protection – Half Moon Fire, 1929, GNPA 11818 45 2.6 Properties on Lake McDonald – cabin in Apgar, Web 54 3.1 A Background of Construction – gas shovel, GTSR, 1937, GNPA 11647 57 3.2 Wildlife Studies in the 1930s – George M. -

32Principles and Practices to Successfully Transition To

32 PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES TO SUCCESSFULLY TRANSITION TO U.S. DOD CLOUD COMPUTING DATA CENTERS Tra·di·tion·al • Da·ta • Cen·ters (trə-dĭsh′ə-nəl • dā′tə • sĕn′tərz′). Centralized capital-intensive information technology (IT) assets, which include land, security fences, buildings, power-space-and-cooling, networks, computers, storage devices, operating systems, middleware, databases, development tools, and monitoring systems. Oftentimes, traditional IT applications were assembled one computer, server, rack elevation, or server farm at a time. That is, a computer system with a microprocessor, memory, motherboard, disk drives, network interfaces, operation systems, and input-output devices such as display screens, printers, and portable or removable tape, disk, or solid-state media. Traditional physical computer systems ranged in size from small to extremely large or monolithic. For instance, a computer system may be a laptop, desktop computer, Unix workstation, small rack elevation, small server farm with multiple racks, a building with many server farms, or even a monolithic collection of buildings with multiple data centers or high-performance computing equipment for massively parallel processing applications. About 80% to 90% of IT data centers are in the small to medium-sized range that sit underneath desks, or in conference room corners, hallway closets, or small conference rooms. Typically, small to medium-sized IT data centers were engineered to host a single information system or small ecosystem of highly interrelated applications. Rack elevations allowed engineers to assemble their computer systems one high-performance component at a time for high-performance computing needs, multitasking and multi-user systems, reliability and fault-tolerance, or fast network delivery. -

Why the Human Factor Is Still the Central Issue

April/May 2017 datacenterdynamics.com Why the human factor is still the central issue 10 beautiful data centers Finding new frontiers Re-shaping servers Here are some facilities that manage to Building a data center is hard They looked solid and unchanging, but get their work done, and still impress us enough. Building one in Angola now servers are being remolded by the with their looks is even tougher creative minds of the industry Contents April/May 2017 27 ON THE COVER 18 Powered by people NEWS 07 Top Story Vantage bought by investment consortium 07 In Brief 14 NTT to develop data centers for connected cars FEATURES 24 Tying down the cloud 27 New data center frontiers 37 Re-shaping servers OPINION 40 23 Data centers are fired by a human heart 46 Max Smolaks is a ghost in a shell REGIONAL FEATURES 14 LATAM Open source IoT protects Mexican bank 18 16 APAC Indonesia ups its game 37 DCD COMMUNITY 40 Dreaming of Net Zero energy The best discussion from DCD Zettastructure, for your delectation 42 Preview: DCD>Webscale and EnergySmart Find out what we have up 24 our sleeves EDITOR’S PICK 30 Top 10 beautiful data centers Data centers don’t have to be boring sheds. These ten facilities paid attention to their looks, and we think it paid off. Nominate your favorite for a new 16 30 DCD Award! Issue 21 • April/May 2017 3 HEAD OFFICE From the Editor 102–108 Clifton Street London EC2A 4HW % +44 (0) 207 377 1907 Let's hear it for MEET THE TEAM Peter Judge Global Editor the humans! @Judgecorp Max Smolaks News Editor mazon's S3 storage We aren't looking just for @MaxSmolax service went down architectural excellence. -

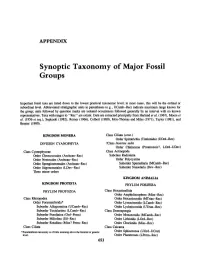

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Software Studies: a Lexicon, Edited by Matthew Fuller, 2008

fuller_jkt.qxd 4/11/08 7:13 AM Page 1 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• S •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••new media/cultural studies ••••software studies •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• O ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• F software studies\ a lexicon ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• T edited by matthew fuller Matthew Fuller is David Gee Reader in ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• This collection of short expository, critical, Digital Media at the Centre for Cultural ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• W and speculative texts offers a field guide Studies, Goldsmiths College, University of to the cultural, political, social, and aes- London. He is the author of Media ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• thetic impact of software. Computing and Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and A digital media are essential to the way we Technoculture (MIT Press, 2005) and ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• work and live, and much has been said Behind the Blip: Essays on the Culture of ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• -

Betts Et Al 2018

Citation for published version: Betts, HC, Puttick, MN, Clark, JW, Williams, TA, Donoghue, PCJ & Pisani, D 2018, 'Integrated genomic and fossil evidence illuminates life’s early evolution and eukaryote origin', Nature Ecology & Evolution, vol. 2, pp. 1556-1562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0644-x DOI: 10.1038/s41559-018-0644-x Publication date: 2018 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in Nature Ecology and Evolution. The final authenticated version is available online at: 10.1038/s41559-018-0644-x University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1 Integrated genomic and fossil evidence illuminates life’s early evolution and 2 eukaryote origins 3 4 Holly C. Betts1, Mark N. Puttick1, James W. Clark1, Tom A. Williams1,2, Philip C. J. Donoghue1, Davide 5 Pisani*1,2 6 7 Schools of Earth1 and Biological2 Sciences, University of Bristol, Life Sciences Building, Tyndall 8 Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TQ, UK 9 * Author for correspondence Email: [email protected] 10 11 Establishing a unified timescale for the early evolution of Earth and Life is challenging and mired in 12 controversy because of the paucity of fossil evidence, the difficulty of interpreting it, and dispute 13 over the deepest branching relationships in the tree of life. -

Bill Laboon Friendly Introduction Version Control: a Brief History

Git and GitHub: A Bill Laboon Friendly Introduction Version Control: A Brief History ❖ In the old days, you could make a copy of your code at a certain point, and release it ❖ You could then continue working on your code, adding features, fixing bugs, etc. ❖ But this had several problems! VERSION 1 VERSION 2 Version Control: A Brief History ❖ Working with others was difficult - if you both modified the same file, it could be very difficult to fix! ❖ Reviewing changes from “Release n” to “Release n + 1” could be very time-consuming, if not impossible ❖ Modifying code locally meant that a crash could take out much of your work Version Control: A Brief History ❖ So now we have version control - a way to manage our source code in a regular way. ❖ We can tag releases without making a copy ❖ We can have numerous “save points” in case our modifications need to be unwound ❖ We can easily distribute our code across multiple machines ❖ We can easily merge work from different people to the same codebase Version Control ❖ There are many kinds of version control out there: ❖ BitKeeper, Perforce, Subversion, Visual SourceSafe, Mercurial, IBM ClearCase, AccuRev, AutoDesk Vault, Team Concert, Vesta, CVSNT, OpenCVS, Aegis, ArX, Darcs, Fossil, GNU Arch, BitKeeper, Code Co-Op, Plastic, StarTeam, MKS Integrity, Team Foundation Server, PVCS, DCVS, StarTeam, Veracity, Razor, Sun TeamWare, Code Co-Op, SVK, Fossil, Codeville, Bazaar…. ❖ But we will discuss git and its most popular repository hosting service, GitHub What is git? ❖ Developed by Linus Torvalds ❖ Strong support for distributed development ❖ Very fast ❖ Very efficient ❖ Very resistant against data corruption ❖ Makes branching and merging easy ❖ Can run over various protocols Git and GitHub ❖ git != GitHub ❖ git is the software itself - GitHub is just a place to store it, and some web-based tools to help with development. -

Fossilizing Netbsd: the Road to Modern Version Control

Fossilizing NetBSD: The road to modern version control J¨orgSonnenberger <[email protected]> October 3, 2011 Abstract This paper discusses cvs2fossil, a new repository conversion tool for CVS. It gives an overview of how different CVS features are handled and discusses some issues found in real world repositories. The second part analyses the performance of Fossil and compares it to other VCSs. 1 Introduction The NetBSD project has successfully deployed CVS for over one and a half decades. The main modules, pkgsrc and src, provide a huge challenge for any replacement. The pkgsrc module challenges scalability by having over 60,000 files per working copy and a total of over 100,000 files in the repository. The src module challenges scalability both in terms of raw size (4.3GB of RCS files) and the large history of 240,000 change sets. Over the last three years a number of attempts to provide conversions to modern version control systems (VCS) have been made. The different VCS and the associated conversion tools all have different shortcomings and no clean consensus could be reached to move into one direction or another. One important tool is Simon Schubert's fromcvs. 1 It was the only option for continously replicating the CVS changes into Git without breaking the normal updating process of the target VCS. This raised the question of how much work a RCS/CVS conversion tool would be that fits the requirements of NetBSD: • Be faithful: honour RCS keywords. • Be smart: properly deal with vendor branches and magic CVS revisions. • Be fast: finish in much less than a day on reasonable modern hardware.