Carl Jung, Folklore, and the Caduceus and Ouroboros in Alchemy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Argonautica, Book 1;

'^THE ARGONAUTICA OF GAIUS VALERIUS FLACCUS (SETINUS BALBUS BOOK I TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY H. G. BLOMFIELD, M.A., I.C.S. LATE SCHOLAR OF EXETER COLLEGE, OXFORD OXFORD B. H. BLACKWELL, BROAD STREET 1916 NEW YORK LONGMANS GREEN & CO. FOURTH AVENUE AND 30TH STREET TO MY WIFE h2 ; ; ; — CANDIDO LECTORI Reader, I'll spin you, if you please, A tough yarn of the good ship Argo, And how she carried o'er the seas Her somewhat miscellaneous cargo; And how one Jason did with ease (Spite of the Colchian King's embargo) Contrive to bone the fleecy prize That by the dragon fierce was guarded, Closing its soporific eyes By spells with honey interlarded How, spite of favouring winds and skies, His homeward voyage was retarded And how the Princess, by whose aid Her father's purpose had been thwarted, With the Greek stranger in the glade Of Ares secretly consorted, And how his converse with the maid Is generally thus reported : ' Medea, the premature decease Of my respected parent causes A vacancy in Northern Greece, And no one's claim 's as good as yours is To fill the blank : come, take the lease. Conditioned by the following clauses : You'll have to do a midnight bunk With me aboard the S.S. Argo But there 's no earthly need to funk, Or think the crew cannot so far go : They're not invariably drunk, And you can act as supercargo. — CANDIDO LECTORI • Nor should you very greatly care If sometimes you're a little sea-sick; There's no escape from mal-de-mer, Why, storms have actually made me sick : Take a Pope-Roach, and don't despair ; The best thing simply is to be sick.' H. -

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Alchemical Journey Into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales

Studia Religiologica 51 (1) 2018, s. 33–45 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.18.003.9492 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Alchemical Journey into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales Emilia Wieliczko-Paprota https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8662-6490 Institute of Polish Language and Literature University of Gdańsk [email protected] Abstract This article demonstrates the importance of alchemical symbolism in Victorian fairy tales. Contrary to Jungian analysts who conceived alchemy as forgotten knowledge, this study shows the vivid tra- dition of alchemical symbolism in Victorian literature. This work takes the readers through the first stage of the alchemical opus reflected in fairy tale symbols, explains the psychological and spiritual purposes of alchemy and helps them to understand the Victorian visions of mystical transforma- tion. It emphasises the importance of spirituality in Victorian times and accounts for the similarity between Victorian and alchemical paths of transformation of the self. Keywords: fairy tales, mysticism, alchemy, subconsciousness, psyche Słowa kluczowe: bajki, mistyka, alchemia, podświadomość, psyche Victorian interest in alchemical science Nineteenth-century fantasy fiction derived its form from a different type of inspira- tion than modern fantasy fiction. As Michel Foucault accurately noted, regarding Flaubert’s imagination, nineteenth-century fantasy was more erudite than imagina- tive: “This domain of phantasms is no longer the night, the sleep of reason, or the uncertain void that stands before desire, but, on the contrary, wakefulness, untir- ing attention, zealous erudition, and constant vigilance.”1 Although, as we will see, Victorian fairy tales originate in the subconsciousness, the inspiration for symbolic 1 M. Foucault, Fantasia of the Library, [in:] Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, D.F. -

The Symbolism of the Dragon

1 THE SYMBOLISM OF THE DRAGON Chinese flying dragon (courtesy of dreamstime.com Ensiferrum 7071168) THE PRIMORDIAL SEVEN, THE FIRST SEVEN BREATHS OF THE DRAGON OF WISDOM, PRODUCE IN THEIR TURN FROM THEIR HOLY CIRCUMGYRATING BREATHS THE FIERY WHIRLWIND. The Stanzas of Dzyan Out of the whirlwind spoke the voice that ignites, that sounds like no voice ever heard. It is, instead, a flame that swirls down out of yawning darkness and scorches the flanks of the trembling world. Amongst the clouds gathered in storm, its fiery curves are sometimes glimpsed and the scraping of its taloned feet echo up the blackened caverns leading to the bowels of the earth. These are aspects of its voice . extensions of its flaming breath. They shine like glittering scales spiralling through the atmosphere. They project forth in the wake of that thunderous tone which issues from the depths of the very source of sound, from the primordial throat which opens out to another world. Thus it is that dragons float at the edge of the universe and near the apertures leading to unknown but frightening realms. Their fiery breath resounds and their reptilian form expands and contracts into myriad shapes described in thousands of stories the world over. But their exact nature remains a mystery and, despite their legendary reputation, for many persons they have never existed. It has been held that the dragon, "while sacred and to be worshipped, has within himself something still more of the divine nature of which it is better to remain in ignorance". Something double-edged is suggested here, and the question of the existence of the dragon deepens to become one of how to approach the Divine without being incinerated by its lower emanations. -

Secret Traditions in the Modern Tarot: Folklore and the Occult Revival

Secret Traditions in the Modern Tarot: Folklore and the Occult Revival I first encountered the evocative images of the tarot, as no doubt many others have done, in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. This led to Pamela Coleman Smith’s tarot deck, and from there to the idiosyncratic writings of A.E. Waite with its musings on the Grail, on ‘secret doctrines’ and on the nature of mystical experience. Revival of interest in the tarot and the proliferation of tarot decks attests to the vibrancy of this phenomenon which appeared in the context of the eighteenth century occult revival. The subject is extensive, but my topic for now is the development of the tarot cards as a secret tradition legend in Britain from the late 1880’s to the 1930’s. (1) During this period, ideas about the nature of culture drawn from folklore and anthropological theory combined with ideas about the origins of Arthurian literature and with speculations about the occult nature of the tarot. These factors working together created an esoteric and pseudo-academic legend about the tarot as secret tradition. The most recent scholarly work indicates that tarot cards first appeared in Italy in the fifteenth century, while speculations about their occult meaning formed part of the French occult revival in the late eighteenth century. (Dummett 1980, 1996 ) The most authoritative historian of tarot cards, the philosopher Michael Dummett, is dismissive of occult and divinatory interpretations. Undoubtedly, as this excellent works points out, ideas about the antiquity of tarot cards are dependent on assumptions made at a later period, and there is a tendency among popular books to repeat each other rather than use primary sources. -

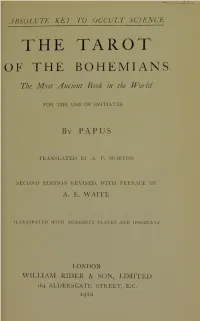

The Tarot of the Bohemians : the Most Ancient Book in the World

IBSOLUTE KET TO OCCULT SCIENCE THE TAROT ÜF THE BOHEMIANS The Most Ancient Book in the World FOR THE USE OF INITIATES By papus TRANSLATED BY A. P. MORTON SECOND EDITION REVISED, WITH PREFACE B Y A. E. WAITE ILLUSTRATED WITH N UMEROU S PLATES AND WOODCUTS LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LIMITED 164 ALDERSGATE STREET, E.C. 1910 Absolute Key to Oocult Science Frontispicce 2) BVÜ W Wellcome Libraty i forthe Histôry standing Il and ififcteï -, of Medi Printed by Ballantyne, HANSON &* Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION An assumption of some kind being of common con- venience, that the line of least résistance may be pursued thereafter, I will open the présent considéra- tion by assuming that those who are quite unversed in the subject hâve referred to the pages which follow, and hâve thus become aware that the Tarot, on its external of that, side, is the probable progenitor playing-cards ; like these, it has been used for divination and for ail but that behind that is understood by fortune-telling ; this it is held to hâve a higher interest and another quality of importance. On a simple understanding, it is of allegory; it is of symbolism, on a higher plane; and, in fine, it is of se.cret doctrine very curiously veiled. The justification of these views is a different question; I am concerned wit>h ihe statement of fact are and this being said, I can that such views held ; pass to my real business, which" is in part critical and in part also explanatory, though not exactly on the elementary side. -

The Story of the Three Women Who Created ARAS

ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2020 Figure 1 The view from Eranos: the mountains over Lago Maggiore. (Photographer: Catherine Ritsema. © Eranos Foundation, Ascona. All rights reserved) The Story of the Three Women Who Created ARAS Ami Ronnberg (ARAS, Curator of Special Projects) The images in this paper are strictly for educational use and are protected by United States copyright laws. 1 Unauthorized use will result in criminal and civil penalties. ARAS Connections Issue 4, 2020 ARAS, The Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism has a long history, reaching back to the early 1930s in Switzerland. Many known and unknown contributors have been part of making ARAS what it is today, a national organization with centers in New York City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, as well as ARAS Online, serving visitors from many other countries. But it all began with three remarkable women who dedicated their lives to exploring the transformations of the psyche – and creating an actual place to do this, each in her own way. Figure 2 Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn at Eranos in the 1930s-1940s. (Photographer Margarethe Fellerer. © Eranos Foundation, Ascona. All rights reserved) The time is the beginning of the 20th century when we first meet Olga-Froebe- Kapteyn, the first woman of the ARAS lineage. Olga (I hope she and the other women would allow me to use their first names) – Olga was born in 1881 in London. Her parents were Dutch. Her father Albert Kapteyn was an inventor, a photographer and The images in this paper are strictly for educational use and are protected by United States copyright laws. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Bollingen Series, –

Bollingen Series, – Bollingen Series, named for the small village in Switzerland where Carl Gustav Jung had a private retreat, was originated by the phi- lanthropist Paul Mellon and his first wife, Mary Conover Mellon, in . Both Mellons were analysands of Jung in Switzerland in the s and had been welcomed into his personal circle, which included the eclectic group of scholars who had recently inaugu- rated the prestigious conferences known as the Eranos Lectures, held annually in Ascona, Switzerland. In the couple established Bollingen Foundation as a source of fellowships and subventions related to humanistic scholarship and institutions, but its grounding mission came to be the Bollin- gen book series. The original inspiration for the series had been Mary Mellon’s wish to publish a comprehensive English-language translation of the works of Jung. In Paul Mellon’s words,“The idea of the Collected Works of Jung might be considered the central core, the binding factor, not only of the Foundation’s general direction but also of the intellectual temper of Bollingen Series as a whole.” In his famous Bollingen Tower, Jung pursued studies in the reli- gions and cultures of the world (both ancient and modern), sym- bolism, mysticism, the occult (especially alchemy), and, of course, psychology. The breadth of Jung’s interests allowed the Bollingen editors to attract scholars, artists, and poets from among the brightest lights in midcentury Europe and America, whether or not their work was “Jungian” in orientation. In the end, the series was remarkably eclectic and wide-ranging, with fewer than half of its titles written by Jung or his followers. -

{FREE} the Collected Works of C.G. Jung: Alchemical Studies V. 13

THE COLLECTED WORKS OF C.G. JUNG: ALCHEMICAL STUDIES V. 13 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK C. G. Jung,Gerhard Adler,R. F. C. Hull | 528 pages | 21 Aug 1983 | Princeton University Press | 9780691018492 | English | New Jersey, United States The Collected Works of C.G. Jung: Alchemical Studies v. 13 PDF Book Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review. Judith Chimowitz rated it it was amazing Nov 06, Edward rated it it was amazing Jan 11, With this admission the only thing redeemable from this book is the excellent bibliography. Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. Overall, this book discusses the philosophical and religious aspects of alchemy , as alchemy was introduced more as a religion than a science. Bollingen Tower C. As a current record of all of C. Laura rated it it was amazing Mar 12, Oct 07, Timothy Ball rated it it was amazing Shelves: tim-s-shelf. Alchemical Studies Collected Works of C. Jung, Volume Alchemical Studies C. One thing that struck me was his influence in fields, like folklore studies and the history of religions, concerned with the study of alchemy. Shelves: psychology. Read more Phone: ext. Jung began his career as a psychiatrist. Other Editions This section comes from two lectures delivered by Jung at the Eranos Conference, Ascona, Switzerland in The central theme of the volume is the symbolic representation of the psychic totality through the concept of the Self, whose traditional The psychological and religious implications of alchemy preoccupied Jung during the last thirty years of his life. -

Tensions Between Scientia and Ars in Medieval Natural Philosophy and Magic Isabelle Draelants

The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic Isabelle Draelants To cite this version: Isabelle Draelants. The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic. Sophie PAGE – Catherine RIDER, eds., The Routledge History of Medieval Magic, p. 169-186, 2019. halshs-03092184 HAL Id: halshs-03092184 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03092184 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This article was downloaded by: University College London On: 27 Nov 2019 Access details: subscription number 11237 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Sophie Page, Catherine Rider The notion of properties Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 Isabelle Draelants Published online on: 20 Feb 2019 How to cite :- Isabelle Draelants. 20 Feb 2019, The notion of properties from: The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Routledge Accessed on: 27 Nov 2019 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

The Paracelsians and the Chemists: the Chemical Dilemma in Renaissance Medicine

Clio Medica, Vol7, No.3, pp. 185-199, 1972 The Paracelsians and the Chemists: the Chemical Dilemma in Renaissance Medicine ALLEN G. DEBUS* Accounts of Renaissance iatrochemistry have traditionally emphasized the con flict over the introduction of chemically prepared medicines. The importance of this cannot be denied, but the texts of the period indicate that this formed only part of a broader debate involving the relationship of chemistry to medicine - and indeed, to nature as a whole. The Paracelsian chemists argued forcefully that much - if not all - of the fabric of ancient medicine should be scrapped, and that a new medicine based on a chemical philosophy of the universe should be offered in its place. For them a proper understanding of the macrocosm and the microcosm would indicate to the true physician the correct cures for diseases. Others - who spoke with no less conviction of the benefits of chemistry for medicine - disagreed with the Paracelsians over the application of chemistry to cosmological problems. For these chemists the introduction of the new remedies and the Paracelsian principles were useful and necessary for the physician, but they were properly to be used along with the traditional Aristotelian-Galenic conceptual scheme. The purpose of the present paper is to give some indication of the deep divisions that separated chemical physicians from each other in this crucial period. By way of background it should be noted that most chemical physicians of the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries did not consider their work to be entirely new. They openly drew upon the writings of Islamic physicians and alchemists as well as a host of Latin scholars of the Middle Ages who had turned to chemical operations as a basic tool for the preparation of medicines.