World Bank Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Dams and Reservoirs 1 List of Dams and Reservoirs

List of dams and reservoirs 1 List of dams and reservoirs The following is a list of reservoirs and dams, arranged by continent and country. Africa Cameroon • Edea Dam • Lagdo Dam • Song Loulou Dam Democratic Republic of Congo • Inga Dam Ethiopia Gaborone Dam in Botswana. • Gilgel Gibe I Dam • Gilgel Gibe III Dam • Kessem Dam • Tendaho Irrigation Dam • Tekeze Hydroelectric Dam Egypt • Aswan Dam and Lake Nasser • Aswan Low Dam Inga Dam in DR Congo. Ghana • Akosombo Dam - Lake Volta • Kpong Dam Kenya • Gitaru Reservoir • Kiambere Reservoir • Kindaruma Reservoir Aswan Dam in Egypt. • Masinga Reservoir • Nairobi Dam Lesotho • Katse Dam • Mohale Dam List of dams and reservoirs 2 Mauritius • Eau Bleue Reservoir • La Ferme Reservoir • La Nicolière Reservoir • Mare aux Vacoas • Mare Longue Reservoir • Midlands Dam • Piton du Milieu Reservoir Akosombo Dam in Ghana. • Tamarind Falls Reservoir • Valetta Reservoir Morocco • Aït Ouarda Dam • Allal al Fassi Dam • Al Massira Dam • Al Wahda Dam • Bin el Ouidane Dam • Daourat Dam • Hassan I Dam Katse Dam in Lesotho. • Hassan II Dam • Idriss I Dam • Imfout Dam • Mohamed V Dam • Tanafnit El Borj Dam • Youssef Ibn Tachfin Dam Mozambique • Cahora Bassa Dam • Massingir Dam Bin el Ouidane Dam in Morocco. Nigeria • Asejire Dam, Oyo State • Bakolori Dam, Sokoto State • Challawa Gorge Dam, Kano State • Cham Dam, Gombe State • Dadin Kowa Dam, Gombe State • Goronyo Dam, Sokoto State • Gusau Dam, Zamfara State • Ikere Gorge Dam, Oyo State Gariep Dam in South Africa. • Jibiya Dam, Katsina State • Jebba Dam, Kwara State • Kafin Zaki Dam, Bauchi State • Kainji Dam, Niger State • Kiri Dam, Adamawa State List of dams and reservoirs 3 • Obudu Dam, Cross River State • Oyan Dam, Ogun State • Shiroro Dam, Niger State • Swashi Dam, Niger State • Tiga Dam, Kano State • Zobe Dam, Katsina State Tanzania • Kidatu Kihansi Dam in Tanzania. -

Environmental Challenges and the Quest for Social Justice in Dam Communities of Nigeria

Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology. Volume 10, Number 2. July 2013 80 Environmental Challenges and the Quest for Social Justice in Dam Communities of Nigeria Ali Arazeem Abdullahi1, Usman A. Raheem2, Saliman Tunde Saliman3. Abstract: While the Nigerian government is focusing its attention on building new dams, the problems and challenges posed by the existing dams to the people and environment across dam communities of Nigeria seem to have been neglected or glossed over. This paper examines the environmental challenges posed by existing dams and how these problems have aggravated grassroots activism and the quest for social justice in dam communities of Nigeria. The paper also examines the institutional arrangement that has been put in place by the government of Nigeria to address these agitations and how effective this might be. On the whole, the paper draws on the concept of community participation to interrogate the socio-cultural and ecologic chasm that certain large dam projects appear to have created between the state and local communities. Keywords: environment, environmental degradation, Dams; HYPADEC; Community participation, Nigeria. Background Dams, especially large ones, function to provide water and energy; they are therefore indispensable mechanisms for economic growth. Large dams4 are also centres of attraction for travelers and tourists. They provide employment for the unemployed and are rich sources of fresh fishes. Following the importance attached to large dams, reports have shown that between 30% and 40% of irrigated land worldwide depend on dams while 19% of world electricity is generated from them (World Commission on Dams [WCD], 2000). By the end of the 20th century, as many as 45,000 large dams have been built across the world (WCD, 2000) with a staggering $2 trillion spent on them (International Rivers Network, [IRN], 2003). -

Supporting Report 6 Water Resources Management Plan

SUPPORTING REPORT 6 WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PLAN WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PLAN Water Resources Management Plan SR6.1 Operation and Maintenance of Existing Dams SR6.1.1 Enhancement of Dam Management SR6.1.2 Dam Safety Management SR6.1.3 Basic Concept for Dam Modification/Rehabilitation SR6.2 Hydrological Monitoring SR6.2.1 Nigeria Hydrological Service Agency (NIHSA) SR6.2.2 Hydrological Monitoring for Surface Water SR6.3 Consideration of Risk Associated with Climate Change and Trans‐boundary Waters SR6.3.1 Climate Change SR6.3.2 Trans‐boundary Water SR6.3.3 Coping Strategy on Risk associate with Climate Change and Trans‐boundary Water SR6.4 Water Environment Management SR6.4.1 Water Environment Conservation SR6.4.2 Water Quality Management SR6.4.3 Problems and Issues on Water Environment Management SR6.4.4 Proposed Plans for Water Environment Management Improvement SR6.5 Water Allocation and Regulation SR6.5.1 Current Condition and Issues on Water Allocation and Regulation SR6.5.2 Proposed Framework on Water Allocation and Regulation SR6.5.3 Proposed Projects The Project for Review and Update of Nigeria National Water Resources Master Plan Contents Page SR 6.1 Operation and Maintenance of Existing Dams ................................................................. SR6-1 SR6.1.1 Enhancement of Dam Management .................................................................................... SR6-1 SR6.1.2 Dam Safety Management.................................................................................................... SR6-4 -

Contribution of Sokoto Rima River Basin Development Authority to Rural Development in Sokoto State Nigeria

CONTRIBUTION OF SOKOTO RIMA RIVER BASIN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY TO RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN SOKOTO STATE NIGERIA 2005- 2010 BY Mohammed Yabo UMARU Ph. D/Admin/09757/2006-2007 BEING DESSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POST GRADUATE STUDIES AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY ZARIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION MARCH 2016 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation entitled contribution of Sokoto Rima River Basin Development Authority (SRRBDA) to Rural Development in Sokoto State 2005-2010 is the result of my own research work and it has been written by me. The work embodied in this dissertation is original and has not been submitted in part or full for any degree of this University or any other University. All works cited are duly acknowledged. UMARU, MUHAMMED YABO ………………… …………… NAME OF STUDENT SIGNATURE DATE i CERTIFICATION This thesis entitled “Contribution of Sokoto Rima River Basin Development Authority (SRRBDA) to Rural Development in Sokoto State 2005-2010” by Mohammed Yabo UMARU meets the regulations governing the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Public Administration) of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. ____________________________ _____________________ Prof. A.A. Anyebe Date Chairman, Supervisory Committee ____________________________ ___________________ Dr. S.B Abdulkareem Date Member, Supervisory Committee _________________________ _________________ Prof S.A Abdullahi Date Member,Supervisory Committee ___________________________ __________________ Dr. H.A Yusuf Date Head of Department __________________________ _________________ Dr Kabiru Bala Date Dean, School of Post Graduate Studies ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my family, friends and well wishers whose encouragement and moral support inspired me to undertake the study despite the daunting challenges of the moment. -

DEVELOPMENT and CHALLENGES of BAKOLORI IRRIGATION PROJECT in SOKOTO STATE, NIGERIA MOHAMMED KUTA YAHAYA University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Nordic Journal of African Studies 11(3): 411-430 (2002) DEVELOPMENT AND CHALLENGES OF BAKOLORI IRRIGATION PROJECT IN SOKOTO STATE, NIGERIA MOHAMMED KUTA YAHAYA University of Ibadan, Nigeria ABSTRACT The paper examines the Bakolori Irrigation Project in Sokoto State, Nigeria and its impact on the intended beneficiaries of the project. The paper reviewed existing irrigation types in Nigeria and implications for sustainable food security in target communities. Also, it provides an insight into the catalogue of consequences that followed the project. Some of these include farmers’ dispossessed of their productive farmlands, fraudulent reallocation processes, inadequate compensation and destruction of economic trees and crops as a result of the irrigation site. Evidences from the project shows that the project brought about certain positive developments in the lives of the target population. However, it was not devoid of undesirable challenges that require considerable attention in development project planning and implementation. These and many other issues surrounding the Bakolori irrigation project raises question on whether the project was a development or a catastrophe? Consequently, suggestions are made on how to design and implement development programmes with an overall view to improving the existing circumstances of the intended beneficiaries. Keywords: Irrigation, Nigeria, development 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND STATEMENT Development is said to be a complex phenomenon based on several factors that have been alleged to be responsible for under-development. Some of these factors are historical, political, economic as well as cultural. However, there are several synonyms to development such as modernization, improvement and change, liberation etc. Thus, development is multi-faceted and human centered, thus its definition has implication for sustainability and relevance to the people affected by changes inherent in development process. -

Environmental and Social Impacts of Reservoirs: Issues and Mitigation - J

OCEANS AND AQUATIC ECOSYSTEMS - Vol. I - Environmental and Social Impacts of Reservoirs: Issues and Mitigation - J. Manatunge, M. Nakayama and T. Priyadarshana ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACTS OF RESERVOIRS: ISSUES AND MITIGATION J. Manatunge and T. Priyadarshana Saitama University, Japan M. Nakayama Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Japan Keywords: Biodiversity, catchments, environmental impacts, involuntary resettlement, social impacts, sustainability Contents 1. Introduction 2. Impacts of Reservoirs 2.1 Benefits of Reservoirs 2.2 Environmental and Ecosystem Impacts 2.2.1 Effects of the Barrier Caused by the Dam 2.2.2 Alteration of the Natural Flow Patterns of Rivers 2.2.3 Indirect Effects of Reservoirs 2.3 Socioeconomic Impacts 2.3.1 Pre-construction 2.3.2 Involuntary Resettlement 2.3.3 Construction 2.3.4 Post-construction 2.3.5 Health and Welfare 2.4 Interrelations and Implications 3. Responding to these Impacts 3.1 Social Impacts 3.1.1 Mitigation of Social Impacts 3.1.2.Resolving the Problem of Equity 3.1.3.Other Project-affected People 3.1.4.Host Populations 3.1.5.Gender Related Issues 3.2 EnvironmentalUNESCO Impacts – EOLSS 3.2.1.Biodiversity and Fish Migration 3.2.2.Sedimentation 3.2.3.Modifications to Hydrological Regime and Downstream Impacts 3.2.4 AfforestationSAMPLE and Conservation Strategies CHAPTERS 3.2.5 Managing Water Quality in the Reservoir and Downstream 3.3 Health Related Problems 3.4 Big Dams or Small Dams? 3.5 Assessing Impacts 3.5.1 Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) 3.5.2 Sectoral Environmental Assessment (Sectoral EA) 3.5.3.Project-specific Assessments—Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Social Impact Assessment (SIA) 3.5.4.Regional Environmental Assessments ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) OCEANS AND AQUATIC ECOSYSTEMS - Vol. -

Dam Structures and Types in Nigeria: Sustainability and Effectiveness

Water Conservation and Management (WCM) 3(1) (2019) 20-26 Water Conservation & Management (WCM) DOI: http://doi.org/10.26480/wcm.01.2019.20.26 ISSN: 2523-5664 (Print) ISSN: 2523-5672 (Online) CODEN: WCMABD REVIEW ARTICLE DAM STRUCTURES AND TYPES IN NIGERIA: SUSTAINABILITY AND EFFECTIVENESS Youdeowei, P.O1; Nwankwoala, H.O2*, Desai, D.D3 1Institute of Geosciences and Space Technology, Rivers State University, Nkpolu-Oroworukwo, Port Harcourt, Nigeria 2Department of Geology, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria 3Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Rivers State University, Nkpolu-Oroworukwo, Port Harcourt, Nigeria *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History: This paper focused on the various dams in Nigeria, their effectiveness with respect to configuration and purpose, sizes, lifespan and sustainability. The study observed the causes of dam failures and also compared their lifespans Received January 2019 to their configuration, location and objectives. The results obtained from this study shows that Nigeria has large, Accepted 2 February 2019 medium and small dams which are also single and multipurpose. The dam structures will live out their lifespan as Available 04 2019 estimated from the designs, work effectively and sustainably except for action of some factors such as change in the 1 hydrology of the dam location, changes in the design criteria and natural disasters. The need to know the degree to Online 27 February which dam structures achieve its expected result or purpose, the lifespan of each dam before rehabilitation and the sustainability of the dams in Nigeria, bringing the attention of the government and private owners to the need of dam construction and maintenance is the basis of this paper. -

World Bank Document

Annex 4 PROCUREMENT PLAN General Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Project Information: Nigeria: Transforming Irrigation Management in Nigeria 2. Bank’s approval Date of the Procurement Plan: May 2014 3. Period covered by this procurement plan: 18 months II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement Public Disclosure Authorized Method Threshold Prior Review Procurement Method US$ Threshold ICB (Goods and Non-consulting Equal to and above 1. services) 5,000,000 All NCB (Goods and Non- Equal to or above 2. Consulting Services) Below 5,000,000 US$ 1,000,000 Equal to or above 3 ICB (Works) 20,000,000 All Equal to or above Public Disclosure Authorized 4. NCB (Works) Below 20,000,000 10,000,000 Shopping (Goods) Below US$ 100,000 None Shopping (Vehicles) - From 1st line distributors Below US$ 500,000 None 5. Shopping (Works) Below US$ 200,000 None Public Disclosure Authorized 2. Summary of the Procurement Packages planned during the first 18 months after project effectiveness 3. Procurement Packages with Methods 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ref Description Estimated Procureme Domestic Review Comments . Cost nt Preferen by Bank No. US$ Method ce (Prior / million (yes/no) Post) 01 Rehabilitation of 115 ICB No Prior Bakalori Dam and Rehabilitation/Impr ovement of Bakalori Irrigation Scheme 02 Rehabilitation and 85 ICB No Prior Improvement of Kano Irrigation Scheme 03 Rehabilitation and 60 ICB No Prior Extension of Hadejia Valley Irrigation Scheme 04 Rehabilitation of 6 40 ICB No Prior No. -

Hadejia-Nguru Wetlands 2003.Pdf

AN OVERVIEW OF THE CONTEXT OF THE JEWEL PROJECT: ACCESS RIGHTS AND CONFLICT OVER COMMON POOL RESOURCES IN THE HADEJIA-NGURU WETLANDS Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This report was prepared for ITAD Ltd., the consultancy company managing the JEWEL Project in the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands for DFID, Nigeria. Cambridge, 20 August 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................................................................1 TABLES .................................................................................................................................................1 FIGURES................................................................................................................................................1 PHOTOS.................................................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................1 1. The global and African context of wetlands .......................................................................................1 2. Background to the Hadejia-Nguru Wetlands......................................................................................2 3. -

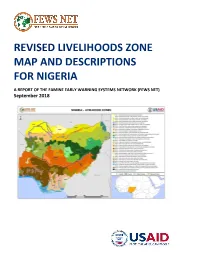

Nigeria Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions 2018

REVISED LIVELIHOODS ZONE MAP AND DESCRIPTIONS FOR NIGERIA A REPORT OF THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) September 2018 NIGERIA Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions September 2018 Acknowledgements and Disclaimer This report reflects the results of the Livelihood Zoning Plus exercise conducted in Nigeria in July to August 2018 by FEWS NET and partners: the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMA&RD) and the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the United Nations World Food Program, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, and various foundation and non-government organizations working to improve the lives and livelihoods of the people of Nigeria. The Livelihood Zoning Plus workshops whose results are the subject of this report were led by Julius Holt, consultant to FEWS NET, Brian Svesve, FEWS NET Regional Food Security Specialist – Livelihoods and Stephen Browne, FEWS NET Livelihoods Advisor, with technical support from Dr. Erin Fletcher, consultant to FEWS NET. The workshops were hosted and guided by Isa Mainu, FEWS NET National Technical Manager for Nigeria, and Atiku Mohammed Yola, FEWS NET Food Security and Nutrition Specialist. This report was produced by Julius Holt from the Food Economy Group and consultant to FEWS NET, with the support of Nora Lecumberri, FEWS NET Livelihoods Analyst, and Emma Willenborg, FEWS NET Livelihoods Research Assistant. This report will form part of the knowledge base for FEWS NET’s food security monitoring activities in Nigeria. The publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006, Task Order 1 (AID-OAA-TO-12- 00003), TO4 (AID-OAA-TO-16-00015). -

Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Irrigated Rice Productivity in Nigeria

THE NIGERIAN RICE ECONOMY IN A COMPETITIVE WORLD: CONSTRAINTS, OPPORTUNITIES AND STRATEGIC CHOICES Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Irrigated Rice Productivity in Nigeria By M. Kebbeh, S. Haefele and S. O. Fagade1 September 2003 West Africa Rice Development Association (WARDA)2 Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire 1 The authors are respectively production economist , WARDA-Saint Louis, Senegal, agronomist, IRRI (former agronomist, WARDA-Saint Louis, Senegal) and consultant.. 2 The study is part of a USAID-funded project implemented by WARDA. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or WARDA. Table of contents 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Goal and Objectives ...............................................................................................................2 2 Study Methodology .........................................................................................................................2 2.1 Sample Selection....................................................................................................................2 2.2 Data collection........................................................................................................................3 3 Overview of Study Sample..............................................................................................................4 3.1 South Chad Irrigation Project -

Operational Performance of Ikere-Gorge Dam in Iseyin Local Government Area of Oyo State, South-Western Nigeria

International Journal of Advanced Academic Research | Arts, Humanities & Education | ISSN: 2488-9849 Vol. 2, Issue 8 (August 2016) OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF IKERE-GORGE DAM IN ISEYIN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF OYO STATE, SOUTH-WESTERN NIGERIA OYEDEMI OYELEKAN ADEYEMO Department of Geography, College of Education, Lanlate, Oyo State, Nigeria. ABSTRACT This paper assessed the Operational Performance of Ikere Gorge Dam in Iseyin Local Government Area of Oyo State. In achieving this aim, the primary data were collected through personal visitation to the site of the dam, direct observation, oral interview and the administration of 300 questionnaire in the eight selected settlement of Ikere and its environs, and middle Ogun-Osun irrigation scheme as well as Iseyin metropolis. The simple random sampling technique was used. Secondary data were sourced from internet, journals, Ogun- Osun River Basin Development Authority. The findings revealed that, Ikere dam is being under-utilized in areas of fishing, tourism and irrigation. It was further revealed that the potentials of the dam were not tapped at all in the areas of power generation and water supply. Based on the findings, the following recommendations were made: Rehabilitation of the road leading to the dam site from Iseyin, private investors’ participation in the tapping of the dam’s potentials, provision of steady supply of electricity to pump water for irrigation. Others are procurement and maintenance of irrigation equipments to ensure all year round farming. Keywords: Ikere dam, irrigation and potentials BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY The Ikere Gorge Dam is a major earth fill dam in Iseyin Local Government Area of Oyo State in the South West of Nigeria.