Shaping the Bund: Public Spaces and Planning Process in the Shanghai International Settlement, 1843-1943

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listing Des Circuits D'autocross Et De Rallycross Et

CIRCUITS ET PARCOURS INTERNATIONAUX INTERNATIONAL CIRCUITS AND COURSES Adresse, localisation, tracé et information concernant les circuits; Listing des circuits d’Autocross et de Rallycross et des parcours de course de côte Tous les dessins de cette section sont strictement le copyright de la FIA et ne peuvent être reproduits sans autorisation écrite préalable. Abréviations L Longueur du circuit S Sens de la course P Pôle W Largeur de référence Prendre note Un circuit ou un parcours est inclus dans cette section sur la base de son activité générale en matière de compétition internationale mais ne signifie pas l’attribution d’un statut particulier ou une quelconque reconnaissance de la part de la FIA. Les détails de la situation géographique des circuits sont fournis sous la forme d’une carte simplifiée (nord en haut, sud en bas). Ces cartes, qui ne sont pas toutes dessinées à la même échelle, n’ont pour but qu’une indication de base, et devraient être lues de concert avec une carte détaillée de la région en question. Circuits: addresses, locations, layouts and information; List of Autocross and Rallycross circuits and Hill-Climb courses All the drawings in this section are strictly the copyright of the FIA and may not be reproduced without prior permission in writing. Abbreviations L Circuit length S Direction of racing P Pole position W Reference width Please note A circuit or course is included in this section on the basis of its general international competition activity, but does not infer any particular status or recognition on the part of the FIA. -

The German-American Bund: Fifth Column Or

-41 THE GERMAN-AMERICAN BUND: FIFTH COLUMN OR DEUTSCHTUM? THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By James E. Geels, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1975 Geels, James E., The German-American Bund: Fifth Column or Deutschtum? Master of Arts (History), August, 1975, 183 pp., bibliography, 140 titles. Although the German-American Bund received extensive press coverage during its existence and monographs of American politics in the 1930's refer to the Bund's activities, there has been no thorough examination of the charge that the Bund was a fifth column organization responsible to German authorities. This six-chapter study traces the Bund's history with an emphasis on determining the motivation of Bundists and the nature of the relationship between the Bund and the Third Reich. The conclusions are twofold. First, the Third Reich repeatedly discouraged the Bundists and attempted to dissociate itself from the Bund. Second, the Bund's commitment to Deutschtum through its endeavors to assist the German nation and the Third Reich contributed to American hatred of National Socialism. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION... ....... 1 II. DEUTSCHTUM.. ......... 14 III. ORIGIN AND IMAGE OF THE GERMAN- ... .50 AMERICAN BUND............ IV. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE BUND AND THE THIRD REICH....... 82 V. INVESTIGATION OF THE BUND. 121 VI. CONCLUSION.. ......... 161 APPENDIX....... .............. ..... 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY......... ........... -

A Neighbourhood Under Storm Zhabei and Shanghai Wars

European Journal of East Asian Studies EJEAS . () – www.brill.nl/ejea A Neighbourhood under Storm Zhabei and Shanghai Wars Christian Henriot Institut d’Asie orientale, Université de Lyon—Institut Universitaire de France [email protected] Abstract War was a major aspect of Shanghai history in the first half of the twentieth century. Yet, because of the particular political and territorial divisions that segmented the city, war struck only in Chinese-administered areas. In this paper, I examine the fate of the Zhabei district, a booming industrious area that came under fire on three successive occasions. Whereas Zhabei could be construed as a success story—a rag-to-riches, swamp-to-urbanity trajectory—the three instances of military conflict had an increasingly devastating impact, from shaking, to stifling, to finally erase Zhabei from the urban landscape. This area of Shanghai experienced the first large-scale modern warfare in an urban setting. The skirmish established the pattern in which the civilian population came to be exposed to extreme forms of violence, was turned overnight into a refugee population, and lost all its goods and properties to bombing and fires. Keywords war; Shanghai; urban; city; civilian; military War is not the image that first comes to mind about Shanghai. In most accounts or scholarly studies, the city stands for modernity, economic prosperity and cultural novelty. It was China’s main financial centre, commercial hub, indus- trial base and cultural engine. In its modern history, however, Shanghai has experienced several instances of war. One could start with the takeover of the city in by the Small Sword Society and the later attempts by the Taip- ing armies to approach Shanghai. -

How Shanghai Does It

How Shanghai Does ItHow DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development Liang, Kidwai, and Zhang Liang, How Shanghai Does It Insights and Lessons from the Highest-Ranking Education System in the World Xiaoyan Liang, Huma Kidwai, and Minxuan Zhang How Shanghai Does It DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development How Shanghai Does It Insights and Lessons from the Highest-Ranking Education System in the World Xiaoyan Liang, Huma Kidwai, and Minxuan Zhang © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

Regeneration and Sustainable Development in the Transformation of Shanghai

Ecosystems and Sustainable Development V 235 Regeneration and sustainable development in the transformation of Shanghai Y. Chen Department of Real estate and Housing, Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology Abstract Globalisation has had an increasing impact on the transformation of Chinese cities ever since China adopted the open door policy in 1978. Many cities in China have been struggling with the challenges of urban regeneration created by the restructuring of the traditional economy and increasing competition between cities for resources, investment and business. The closure of docks, warehouses and industries, and the deteriorating position of traditional urban centres not only created problems but also created exceptional opportunities to reshape cities and create new functions. But this kind of process also generates a series of physical, economic and social consequences for cities to tackle. In many cases the problems exceed the capacity of the local community to adapt and respond. This paper examines a number of urban regeneration projects in Shanghai, in the hope of providing a better understanding of the process of urban regeneration in China and how best to ensure that such regeneration is sustainable. The paper reassesses the aims of regeneration, the mechanisms involved in the regeneration process and its physical, economic and social consequences, discusses how to achieve sustainable development in urban regeneration and makes recommendations for future action. 1 Introduction Global market forces and increasing globalisation are clearly playing a role in the transformation of cities and towns. In most countries urban systems are experiencing dramatic changes brought about by economic restructuring, continuous mass migration and the arrival of immigrants. -

World Expo – Building the Foundations for Shanghai’S Future Shanghai Has Spent Over USD 95 Billion on Developments

April 2010 World Expo – Building the Foundations for Shanghai’s Future Shanghai has spent over USD 95 billion on developments. In addition, the Expo has given infrastructure investment in preparation for the Shanghai an opportunity to implement stricter 2010 World Expo. To reflect the theme of “Better environmental protection and an occasion to City, Better Life” – the Expo investments will make beautify its surroundings, making the city a more Shanghai a more integrated and more accessible attractive place to live, visit, and conduct business. city. The real legacy of the event will come from the opportunities that this new infrastructure The making of a better city creates across Shanghai in all commercial The Expo has played a central role in driving and residential property sectors. Indeed, the the infrastructure build out which is transforming foundations for a new decade of growth and Shanghai. Similar to Beijing’s experience with expansion for the city of Shanghai have been put the Olympics, the Shanghai government has in place. mobilised enormous resources to ensure that all projects are completed on time, and the city can In this paper, we seek to answer three questions: show its best face to the world. As of November • What opportunities does the 2010 World Expo 2008, the total infrastructure investment committed hold for Shanghai real estate? through 2010 was estimated at RMB 500 billion • What are the specific impacts on each (USD 73 billion). Another RMB 150 billion (USD property sector? 22 billion) were newly allocated by the Shanghai government in conjunction with the Central • What are the longer term opportunities that government’s 2008/2009 fiscal stimulus plan – part result from the city’s infrastructure investment? of the response to the global financial crisis. -

Shanghai Before Nationalism Yexiaoqing

East Asian History NUMBER 3 . JUNE 1992 THE CONTINUATION OF Papers on Fa r EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie Barme Assistant Editor Helen 1.0 Editorial Board John Clark Igor de Rachewiltz Mark Elvin (Convenor) Helen Hardacre John Fincher Colin Jeffcott W.J.F. Jenner 1.0 Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Business Manager Marion Weeks Production Oahn Collins & Samson Rivers Design Maureen MacKenzie, Em Squared Typographic Design Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the second issue of EastAsian History in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. The journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, EastAsian History Division of Pacific and Asian History, Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia Phone +61-6-2493140 Fax +61-6-2571893 Subscription Enquiries Subscription Manager, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Rates Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Politics and Power in the Tokugawa Period Dani V. Botsman 33 Shanghai Before Nationalism YeXiaoqing 53 'The Luck of a Chinaman' : Images of the Chinese in Popular Australian Sayings Lachlan Strahan 77 The Interactionistic Epistemology ofChang Tung-sun Yap Key-chong 121 Deconstructing Japan' Amino Yoshthtko-translat ed by Gavan McCormack iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ���Il/I, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Kazai*" -a punishment -

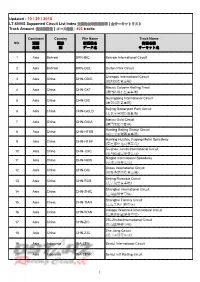

Updated : 10 / 29 / 2018 LT-6000S Supported Circuit List Index 支援的全球賽道清單│全サーキットリスト Track Amount 賽道總數量│コース総数 : 623 Tracks

Updated : 10 / 29 / 2018 LT-6000S Supported Circuit List Index 支援的全球賽道清單│全サーキットリスト Track Amount 賽道總數量│コース総数 : 623 tracks Continent Country File Name Track Name NO. 洲別 國家 賽道檔名 賽道名稱 地域 国 データ名 サーキット名 1 Asia Bahrain BRN-BIC Bahrain International Circuit 2 Asia Bahrain BRN-OUL Oulton Park Circuit Chengdu International Circuit 3 Asia China CHN-CDIC (成都國際賽車場) Macau Coloane Karting Track 4 Asia China CHN-CKT (澳門路環小型賽車場) Guangdong International Circuit 5 Asia China CHN-GIC (廣東國際賽車場) Beijing Goldenport Park Circuit 6 Asia China CHN-GOLD (北京金港國際賽車場) Macau Guia Circuit 7 Asia China CHN-GUIA (澳門東望洋賽道) Hunting Beijing Shunyi Circuit 8 Asia China CHN-HTBS (豪庭北京順義賽車場) Hunting Huizhou Fugang Motor Speedway 9 Asia China CHN-HTHF (豪霆惠州福岗赛车场) Guizhou Junchi International Circuit 10 Asia China CHN-JCIC (贵州骏驰国际赛车场) Ningbo International Speedway 11 Asia China CHN-NBIS (宁波国际赛车场) Ordos International Circuit 12 Asia China CHN-OIC (鄂爾多斯國際賽車場) Beijing Ruisiclub Circuit 13 Asia China CHN-RUS (北京銳思賽車場) Shanghai International Circuit 14 Asia China CHN-SHIC (上海國際賽車場) Shanghai Tianma Circuit 15 Asia China CHN-TIAN (上海天馬山賽車場) Jiangsu Wantrack International Circuit 16 Asia China CHN-WAN (江蘇萬馳國際賽車場) ZIC-Zhuhai International Circuit 17 Asia China CHN-ZIC (珠海國際賽車場) Zhe Jiang Circuit 18 Asia China CHN-ZJC (浙江国际赛车场) 19 Asia Indonesia INA-SEN Sentul International Circuit 20 Asia Indonesia INA-SENK Sentul Int'l Karting circuit 1 Continent Country File Name Track Name NO. 洲別 國家 賽道檔名 賽道名稱 地域 国 データ名 サーキット名 21 Asia India IND-BUD Buddh International Circuit 22 Asia India IND-KMS Kari -

Yangpu Trip Booklet.Indd

Century of the Pacific The How, When and Why of Expanding in China Plus, celebrate the opening of the Bay Area Business Community’s China Landing Pad June 13-18, 2010 Shanghai, China Why Now? There are many reasons why Bay Area companiess have decided now is the time to expand in China. With China’s stunning economic growth, its rapidlyy expanding middle class, the pull of existing customers to move there, the threat of competitorss getting there fi rst, the escalating demand and premiummium price for Bay Area or “American” products and services,vices, a potential prolonged local recession, and the need to bebe inin China in this evermore “global” business world – it’st’s no wonder. Like any new market, business in China comes with challenges. Relationship management is a critical competence, as are strategies to get comfortable with a new business culture and operate in a different language. That said, numerous Bay Area businesses have already braved China and found it an exhilarating, profi table experience. China wants and needs your products and services. They want to build an econ- omy modeled more and more on the Bay Area’s innovation economy. Recogniz- ing the mutual benefi t for our two regions in the coming Century of the Pacifi c, the Bay Area business community is partnering with the business and government community of Shanghai to roll out the red carpet and build a Bay Area landing pad in Shanghai’s dynamic Yangpu District. We hope you join us on this historic trip as we learn how to successfully expand in China, use the Yangpu District as an in depth case study of how to grow in China from the ground up, see one of the most incredible cities humanity has ever built, plus, have a good time. -

China International Import Expo Presentation of Investment Promotion Activities in Hongkou District

China International Import Expo Presentation of Investment Promotion Activities in Hongkou District Shanghai Hongkou District Comm ission of Commerce (Economy) October 1 0, 2018 SHANGHAI HONGKOU Hongkou district is one of the earliest open areas in China, with a deep cultural background and excellent geographical location. On the south side of Hongkou district lies the Huangpu River and the Wusong River. The North Bund of Hongkou district, the old Bund of Huangpu district and the Lujiazui of Pudong New Area form a golden triangle, separated by the Huangpu River. Hongkou district has a total area of 23.48 k㎡, with a resident population of 800,000. 虹 口 上 海 23.4 k㎡ 6340 k㎡ 中 国 9,634,057 k㎡ SHANGHAI HONGKOU Development Planning of Hongkou District Target for 2020 The Northern Science and Technology Innovation Industry Gathering Area mainly includes the Dabaishu Science and Technology Innovation Center, 1.Establish the Shanghai international Fu Dan-Caida Innovation Area, Tongji Innovation Area, etc. We will focus financial center and international shipping on the renewal and utilization of stock plots, industrial plants and industrial parks. center as import ant functional area 2. Establish an influential creative The Central Commercial and Tourist Sports Development Area is mainly including the area of Hongkou football field area, Sichuan entrepreneurial zone North Road Park-Music Valley, and the area of Ruihong Tiandi. The 3. Establish an accessible and diversified key projects include Financial Street Hailun Center etc. Shanghai cultural heritage development zone. Double Loading Area for Financial and Shipping 4. Establish a high quality urban areas that Industry in the North Bund includes the North Bund are suitable for living, working and Business and Cultural District, Zhoushan Road Historical Creative Block ect. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title An Autosegmental-Metrical Model of Shanghainese Tone and Intonation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5hm0n8b7 Author Roberts, Brice David Publication Date 2020 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5hm0n8b7#supplemental Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles An Autosegmental Metrical Model of Shanghainese Tone and Intonation A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Brice David Roberts 2020 © Copyright by Brice David Roberts 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION An Autosegmental-Metrical Model of Shanghainese Tone and Intonation by Brice David Roberts Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor Sun-Ah Jun, Chair This dissertation presents a model of Shanghainese lexical tone and intonation based in the Autosegmental-Metrical framework and develops an annotation system for prosodic events in the language, known as Shanghainese Tones and Break Indices Labeling, or Sh_ToBI. Full- sentence phonetic data from 21 Shanghainese speakers (born 1937-1975) were analyzed. Instead of a syllable tone language with left-dominant sandhi, Shanghainese is analyzed here as a lexical pitch accent language, with three levels of phrasing above the syllable. The lowest level of phrasing is the accentual phrase, which is the domain of the three contrastive pitch accents, H*, L*+H, and L*. These pitch accents are paired with one of two AP-final boundary tones: La/L:a or LHa. La/L:a varies freely between a single low target (La) and a low plateau (L:a), and co-occurs with H* and L*+H. -

Racing Factbook Circuits

Racing Circuits Factbook Rob Semmeling Racing Circuits Factbook Page 2 CONTENTS Introduction 4 First 5 Oldest 15 Newest 16 Ovals & Bankings 22 Fastest 35 Longest 44 Shortest 48 Width 50 Corners 50 Elevation Change 53 Most 55 Location 55 Eight-Shaped Circuits 55 Street Circuits 56 Airfield Circuits 65 Dedicated Circuits 67 Longest Straightaways 72 Racing Circuits Factbook Page 3 Formula 1 Circuits 74 Formula 1 Circuits Fast Facts 77 MotoGP Circuits 78 IndyCar Series Circuits 81 IMSA SportsCar Championship Circuits 82 World Circuits Survey 83 Copyright © Rob Semmeling 2010-2016 / all rights reserved www.wegcircuits.nl Cover Photography © Raphaël Belly Racing Circuits Factbook Page 4 Introduction The Racing Circuits Factbook is a collection of various facts and figures about motor racing circuits worldwide. I believe it is the most comprehensive and accurate you will find anywhere. However, although I have tried to make sure the information presented here is as correct and accurate as possible, some reservation is always necessary. Research is continuously progressing and may lead to new findings. Website In addition to the Racing Circuits Factbook file you are viewing, my website www.wegcircuits.nl offers several further downloadable pdf-files: theRennen! Races! Vitesse! pdf details over 700 racing circuits in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and Austria, and also contains notes on Luxembourg and Switzerland. The American Road Courses pdf-documents lists nearly 160 road courses of past and present in the United States and Canada. These files are the most comprehensive and accurate sources for racing circuits in said countries. My website also lists nearly 5000 dates of motorcycle road races in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Luxembourg and Switzerland, allowing you to see exactly when many of the motorcycle circuits listed in the Rennen! Races! Vitesse! document were used.