UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listing Des Circuits D'autocross Et De Rallycross Et

CIRCUITS ET PARCOURS INTERNATIONAUX INTERNATIONAL CIRCUITS AND COURSES Adresse, localisation, tracé et information concernant les circuits; Listing des circuits d’Autocross et de Rallycross et des parcours de course de côte Tous les dessins de cette section sont strictement le copyright de la FIA et ne peuvent être reproduits sans autorisation écrite préalable. Abréviations L Longueur du circuit S Sens de la course P Pôle W Largeur de référence Prendre note Un circuit ou un parcours est inclus dans cette section sur la base de son activité générale en matière de compétition internationale mais ne signifie pas l’attribution d’un statut particulier ou une quelconque reconnaissance de la part de la FIA. Les détails de la situation géographique des circuits sont fournis sous la forme d’une carte simplifiée (nord en haut, sud en bas). Ces cartes, qui ne sont pas toutes dessinées à la même échelle, n’ont pour but qu’une indication de base, et devraient être lues de concert avec une carte détaillée de la région en question. Circuits: addresses, locations, layouts and information; List of Autocross and Rallycross circuits and Hill-Climb courses All the drawings in this section are strictly the copyright of the FIA and may not be reproduced without prior permission in writing. Abbreviations L Circuit length S Direction of racing P Pole position W Reference width Please note A circuit or course is included in this section on the basis of its general international competition activity, but does not infer any particular status or recognition on the part of the FIA. -

The Creative Artist: a Journal of Theatre and Media Studies, Vol 13, 2, 2017

The Creative Artist: A Journal of Theatre and Media Studies, Vol 13, 2, 2017 MANDARIN CHINESE PINYIN: PRONUNCIATION, ORTHOGRAPHY AND TONE Sunny Ifeanyi Odinye, PhD Department of Igbo, African and Asian Studies Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Pinyin is essential and most fundamental knowledge for all serious learners of Mandarin Chinese. If students are learning Mandarin Chinese, no matter if they are beginners or advanced learners, they should be aware of paramount importance of Pinyin. Good knowledge in Pinyin can greatly help students express themselves more clearly; it can also help them in achieving better listening and reading comprehension. Before learning how to read, write, or pronounce Chinese characters, students must learn pinyin first. This study aims at highlighting the importance of Pinyin and its usage in Mandarin for any students learning Mandarin Chinese. The research work adopts descriptive research method. The work is divided into introduction, body and conclusion. 1. INTRODUCTION Pinyin (spelled sounds) has vastly increased literacy throughout China and beyond; eased the classroom agonies of foreigners studying Mandarin Chinese; afforded the blind a way to read the language in Braille; facilitated the rapid entry of Chinese on computer keyboards and cell phones. "About one billion Chinese citizens have mastered pinyin, which plays an important role in both Chinese language education and international communication," said Wang Dengfeng, vice-chairman of the National Language Committee and director of language department of the Education Ministry. "Hanyu Pinyin not only belongs to China but also belongs to the world. It is now everywhere in our daily lives," Wang said, "Pinyin will continue playing an important role in the modernization of China." (Xinhua News, 2008). -

How Shanghai Does It

How Shanghai Does ItHow DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development Liang, Kidwai, and Zhang Liang, How Shanghai Does It Insights and Lessons from the Highest-Ranking Education System in the World Xiaoyan Liang, Huma Kidwai, and Minxuan Zhang How Shanghai Does It DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development How Shanghai Does It Insights and Lessons from the Highest-Ranking Education System in the World Xiaoyan Liang, Huma Kidwai, and Minxuan Zhang © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

De Sousa Sinitic MSEA

THE FAR SOUTHERN SINITIC LANGUAGES AS PART OF MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA (DRAFT: for MPI MSEA workshop. 21st November 2012 version.) Hilário de Sousa ERC project SINOTYPE — École des hautes études en sciences sociales [email protected]; [email protected] Within the Mainland Southeast Asian (MSEA) linguistic area (e.g. Matisoff 2003; Bisang 2006; Enfield 2005, 2011), some languages are said to be in the core of the language area, while others are said to be periphery. In the core are Mon-Khmer languages like Vietnamese and Khmer, and Kra-Dai languages like Lao and Thai. The core languages generally have: – Lexical tonal and/or phonational contrasts (except that most Khmer dialects lost their phonational contrasts; languages which are primarily tonal often have five or more tonemes); – Analytic morphological profile with many sesquisyllabic or monosyllabic words; – Strong left-headedness, including prepositions and SVO word order. The Sino-Tibetan languages, like Burmese and Mandarin, are said to be periphery to the MSEA linguistic area. The periphery languages have fewer traits that are typical to MSEA. For instance, Burmese is SOV and right-headed in general, but it has some left-headed traits like post-nominal adjectives (‘stative verbs’) and numerals. Mandarin is SVO and has prepositions, but it is otherwise strongly right-headed. These two languages also have fewer lexical tones. This paper aims at discussing some of the phonological and word order typological traits amongst the Sinitic languages, and comparing them with the MSEA typological canon. While none of the Sinitic languages could be considered to be in the core of the MSEA language area, the Far Southern Sinitic languages, namely Yuè, Pínghuà, the Sinitic dialects of Hǎinán and Léizhōu, and perhaps also Hakka in Guǎngdōng (largely corresponding to Chappell (2012, in press)’s ‘Southern Zone’) are less ‘fringe’ than the other Sinitic languages from the point of view of the MSEA linguistic area. -

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2020 Committee: Zev Handel William Boltz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2020 Grainger Lanneau University of Washington Abstract Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor Zev Handel Asian Languages and Literature Middle Chinese glottal stop Ying [ʔ-] initials usually develop into zero initials with rare occasions of nasalization in modern day Sinitic1 languages and Sino-Vietnamese. Scholars such as Edwin Pullyblank (1984) and Jiang Jialu (2011) have briefly mentioned this development but have not yet thoroughly investigated it. There are approximately 26 Sino-Vietnamese words2 with Ying- initials that nasalize. Scholars such as John Phan (2013: 2016) and Hilario deSousa (2016) argue that Sino-Vietnamese in part comes from a spoken interaction between Việt-Mường and Chinese speakers in Annam speaking a variety of Chinese called Annamese Middle Chinese AMC, part of a larger dialect continuum called Southwestern Middle Chinese SMC. Phan and deSousa also claim that SMC developed into dialects spoken 1 I will use the terms “Sinitic” and “Chinese” interchangeably to refer to languages and speakers of the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. 2 For the sake of simplicity, I shall refer to free and bound morphemes alike as “words.” 1 in Southwestern China today (Phan, Desousa: 2016). Using data of dialects mentioned by Phan and deSousa in their hypothesis, this study investigates initial nasalization in Ying-initial words in Southwestern Chinese Languages and in the 26 Sino-Vietnamese words. -

Traditional Chinese Phonology Guillaume Jacques Chinese Historical Phonology Differs from Most Domains of Contemporary Linguisti

Traditional Chinese Phonology Guillaume Jacques Chinese historical phonology differs from most domains of contemporary linguistics in that its general framework is based in large part on a genuinely native tradition. The non-Western outlook of the terminology and concepts used in Chinese historical phonology make this field extremely difficult to understand for both experts in other fields of Chinese linguistics and historical phonologists specializing in other language families. The framework of Chinese phonology derives from the tradition of rhyme books and rhyme tables, which dates back to the medieval period (see section 1 and 2, as well as the corresponding entries). It is generally accepted that these sources were not originally intended as linguistic descriptions of the spoken language; their main purpose was to provide standard character readings for literary Chinese (see subsection 2.4). Nevertheless, these documents also provide a full-fledged terminology describing both syllable structure (initial consonant, rhyme, tone) and several phonological features (places of articulation of consonants and various features that are not always trivial to interpret, see section 2) of the Chinese language of their time (on the problematic concept of “Middle Chinese”, see the corresponding entry). The terminology used in this field is by no means a historical curiosity only relevant to the history of linguistics. It is still widely used in contemporary Chinese phonology, both in works concerning the reconstruction of medieval Chinese and in the description of dialects (see for instance Ma and Zhang 2004). In this framework, the phonological information contained in the medieval documents is used to reconstruct the pronunciation of earlier stages of Chinese, and the abstract categories of the rhyme tables (such as the vexing děng 等 ‘division’ category) receive various phonetic interpretations. -

The Reconstruction of Proto-Yue Vowels

W O R K I N G P A P E R S I N L I N G U I S T I C S The notes and articles in this series are progress reports on work being carried on by students and faculty in the Department. Because these papers are not finished products, readers are asked not to cite from them without noting their preliminary nature. The authors welcome any comments and suggestions that readers might offer. Volume 40(2) 2009 (March) DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA HONOLULU 96822 An Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Institution WORKING PAPERS IN LINGUISTICS: UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA, VOL. 40(2) DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS FACULTY 2009 Victoria B. Anderson Byron W. Bender (Emeritus) Benjamin Bergen Derek Bickerton (Emeritus) Robert A. Blust Robert L. Cheng (Adjunct) Kenneth W. Cook (Adjunct) Kamil Ud Deen Patricia J. Donegan (Co-Graduate Chair) Emanuel J. Drechsel (Adjunct) Michael L. Forman (Emeritus) George W. Grace (Emeritus) John H. Haig (Adjunct) Roderick A. Jacobs (Emeritus) Paul Lassettre P. Gregory Lee Patricia A. Lee Howard P. McKaughan (Emeritus) William O’Grady (Chair) Yuko Otsuka Ann Marie Peters (Emeritus, Co-Graduate Chair) Kenneth L. Rehg Lawrence A. Reid (Emeritus) Amy J. Schafer Albert J. Schütz, (Emeritus, Editor) Ho Min Sohn (Adjunct) Nicholas Thieberger Laurence C. Thompson (Emeritus) ii A RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-YUE VOWELS KAREN HUANG This paper presents an alternative reconstruction of Proto-Yue vowels in the literary stratum. Opposed to previous studies, the rhyme categories are not considered. I analyze the literary stratum of eighteen Yue dialects and reconstruct the vowel system based on the comparative method. -

Shanghai Before Nationalism Yexiaoqing

East Asian History NUMBER 3 . JUNE 1992 THE CONTINUATION OF Papers on Fa r EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie Barme Assistant Editor Helen 1.0 Editorial Board John Clark Igor de Rachewiltz Mark Elvin (Convenor) Helen Hardacre John Fincher Colin Jeffcott W.J.F. Jenner 1.0 Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Business Manager Marion Weeks Production Oahn Collins & Samson Rivers Design Maureen MacKenzie, Em Squared Typographic Design Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the second issue of EastAsian History in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. The journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, EastAsian History Division of Pacific and Asian History, Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia Phone +61-6-2493140 Fax +61-6-2571893 Subscription Enquiries Subscription Manager, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Rates Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Politics and Power in the Tokugawa Period Dani V. Botsman 33 Shanghai Before Nationalism YeXiaoqing 53 'The Luck of a Chinaman' : Images of the Chinese in Popular Australian Sayings Lachlan Strahan 77 The Interactionistic Epistemology ofChang Tung-sun Yap Key-chong 121 Deconstructing Japan' Amino Yoshthtko-translat ed by Gavan McCormack iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ���Il/I, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Kazai*" -a punishment -

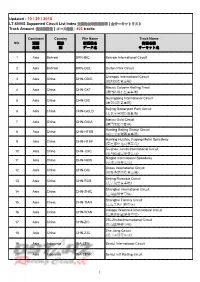

Updated : 10 / 29 / 2018 LT-6000S Supported Circuit List Index 支援的全球賽道清單│全サーキットリスト Track Amount 賽道總數量│コース総数 : 623 Tracks

Updated : 10 / 29 / 2018 LT-6000S Supported Circuit List Index 支援的全球賽道清單│全サーキットリスト Track Amount 賽道總數量│コース総数 : 623 tracks Continent Country File Name Track Name NO. 洲別 國家 賽道檔名 賽道名稱 地域 国 データ名 サーキット名 1 Asia Bahrain BRN-BIC Bahrain International Circuit 2 Asia Bahrain BRN-OUL Oulton Park Circuit Chengdu International Circuit 3 Asia China CHN-CDIC (成都國際賽車場) Macau Coloane Karting Track 4 Asia China CHN-CKT (澳門路環小型賽車場) Guangdong International Circuit 5 Asia China CHN-GIC (廣東國際賽車場) Beijing Goldenport Park Circuit 6 Asia China CHN-GOLD (北京金港國際賽車場) Macau Guia Circuit 7 Asia China CHN-GUIA (澳門東望洋賽道) Hunting Beijing Shunyi Circuit 8 Asia China CHN-HTBS (豪庭北京順義賽車場) Hunting Huizhou Fugang Motor Speedway 9 Asia China CHN-HTHF (豪霆惠州福岗赛车场) Guizhou Junchi International Circuit 10 Asia China CHN-JCIC (贵州骏驰国际赛车场) Ningbo International Speedway 11 Asia China CHN-NBIS (宁波国际赛车场) Ordos International Circuit 12 Asia China CHN-OIC (鄂爾多斯國際賽車場) Beijing Ruisiclub Circuit 13 Asia China CHN-RUS (北京銳思賽車場) Shanghai International Circuit 14 Asia China CHN-SHIC (上海國際賽車場) Shanghai Tianma Circuit 15 Asia China CHN-TIAN (上海天馬山賽車場) Jiangsu Wantrack International Circuit 16 Asia China CHN-WAN (江蘇萬馳國際賽車場) ZIC-Zhuhai International Circuit 17 Asia China CHN-ZIC (珠海國際賽車場) Zhe Jiang Circuit 18 Asia China CHN-ZJC (浙江国际赛车场) 19 Asia Indonesia INA-SEN Sentul International Circuit 20 Asia Indonesia INA-SENK Sentul Int'l Karting circuit 1 Continent Country File Name Track Name NO. 洲別 國家 賽道檔名 賽道名稱 地域 国 データ名 サーキット名 21 Asia India IND-BUD Buddh International Circuit 22 Asia India IND-KMS Kari -

The Phonological Domain of Tone in Chinese: Historical Perspectives

THE PHONOLOGICAL DOMAIN OF TONE IN CHINESE: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES by Yichun Dai B. A. Nanjing University, 1982 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGRFE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the pepartment of Linguistics @ Yichun Dai 1991 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1991 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Yichun Dai DEGREE: Master of Arts (Linguistics) TITLE OF THESIS : The Phonological Domain of Tone in Chinese: Historical Perspectives EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman: Dr. R. C. DeArmond ----------- Dr. T. A. Perry, Senior ~aisor Dr. N. J. Lincoln - ................................... J A. Edmondson, Professor, Department of foreign Languages and Linguistics, University of Texas at Arlington, External Examiner PARTIAL COPYR l GHT L l CENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University L ibrary, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay Author: (signature) (name 1 Abstract This thesis demonstrates how autosegmental licensing theory operates in Chinese. -

LANGUAGE CONTACT and AREAL DIFFUSION in SINITIC LANGUAGES (Pre-Publication Version)

LANGUAGE CONTACT AND AREAL DIFFUSION IN SINITIC LANGUAGES (pre-publication version) Hilary Chappell This analysis includes a description of language contact phenomena such as stratification, hybridization and convergence for Sinitic languages. It also presents typologically unusual grammatical features for Sinitic such as double patient constructions, negative existential constructions and agentive adversative passives, while tracing the development of complementizers and diminutives and demarcating the extent of their use across Sinitic and the Sinospheric zone. Both these kinds of data are then used to explore the issue of the adequacy of the comparative method to model linguistic relationships inside and outside of the Sinitic family. It is argued that any adequate explanation of language family formation and development needs to take into account these different kinds of evidence (or counter-evidence) in modeling genetic relationships. In §1 the application of the comparative method to Chinese is reviewed, closely followed by a brief description of the typological features of Sinitic languages in §2. The main body of this chapter is contained in two final sections: §3 discusses three main outcomes of language contact, while §4 investigates morphosyntactic features that evoke either the North-South divide in Sinitic or areal diffusion of certain features in Southeast and East Asia as opposed to grammaticalization pathways that are crosslinguistically common.i 1. The comparative method and reconstruction of Sinitic In Chinese historical -

Shaping the Bund: Public Spaces and Planning Process in the Shanghai International Settlement, 1843-1943

14th IPHS CONFERENCE 12-15 July 2010 Istanbul-TURKEY SHAPING THE BUND: PUBLIC SPACES AND PLANNING PROCESS IN THE SHANGHAI INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENT, 1843-1943 Yingchun LI, PhD. Student The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong [email protected] Wang WEIJEN, Associate Professor The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong ABSTRACT The Shanghai Bund is the classic symbol of Chinese economic strength and vigor in the early twentieth century. It was one of the most attractive waterfront public open spaces in Asia, and constituted the heart of communal life for both foreign and Chinese communities. This paper investigates the history of the public space of the Shanghai Bund,in terms of its shaping, representing and using. It unveils the four major social parties which had involved in shaping the street gridiron,the public buildings, the public parks, and the waterfront promenade. First to be the British colonial authority that had occasionally compromised to the demands of the Chinese to secure the trade profit. Second is the Chinese authority that had struggled for it conceptual and instrumental control over the foreign settlement. Third is the small group of powerful people called the “Bund Lot Holders” that had demanded the exclusive rights over the Bund. Finally is the ordinary Foreign Land Renters, with the Municipal Council has their Trustee, who had sought to make the Bund into an orderly public spaces for recreation amenity. The paper concludes that the landscape of the Shanghai Bund should not simply be considered as a symbol of “Western modernity”.It also reflected the complicated processes of conflict and compromise among various social parties, in which each party must be seen as participants in the same historical trajectory.