War at the Background of Europe: the Crisis of Mali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Operation Serval to Barkhane

same year, Hollande sent French troops to From Operation Serval the Central African Republic (CAR) to curb ethno-religious warfare. During a visit to to Barkhane three African nations in the summer of 2014, the French president announced Understanding France’s Operation Barkhane, a reorganization of Increased Involvement in troops in the region into a counter-terrorism Africa in the Context of force of 3,000 soldiers. In light of this, what is one to make Françafrique and Post- of Hollande’s promise to break with colonialism tradition concerning France’s African policy? To what extent has he actively Carmen Cuesta Roca pursued the fulfillment of this promise, and does continued French involvement in Africa constitute success or failure in this rançois Hollande did not enter office regard? France has a complex relationship amid expectations that he would with Africa, and these ties cannot be easily become a foreign policy president. F cut. This paper does not seek to provide a His 2012 presidential campaign carefully critique of President Hollande’s policy focused on domestic issues. Much like toward France’s former African colonies. Nicolas Sarkozy and many of his Rather, it uses the current president’s predecessors, Hollande had declared, “I will decisions and behavior to explain why break away from Françafrique by proposing a France will not be able to distance itself relationship based on equality, trust, and 1 from its former colonies anytime soon. solidarity.” After his election on May 6, It is first necessary to outline a brief 2012, Hollande took steps to fulfill this history of France’s involvement in Africa, promise. -

Cross-Currents in French Defense and U.S. Interests by Leo G

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 10 Cross-currents in French Defense and U.S. Interests by Leo G. Michel Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: French Army Colonel Eric Bellot des Minières, right, briefs General Stanley A. McChrystal, USA, at Combat Outpost 42 in Tagab Valley, Afghanistan, March 30, 2010. General McChrystal was commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization International Security Assistance Force and U.S. Forces Afghanistan. Photo by Mark O’Donald Cross-currents in French Defense and U.S. Interests Cross-currents in French Defense and U.S. Interests By Leo G. Michel Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 10 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. -

Africa Yearbook

AFRICA YEARBOOK AFRICA YEARBOOK Volume 10 Politics, Economy and Society South of the Sahara in 2013 EDITED BY ANDREAS MEHLER HENNING MELBER KLAAS VAN WALRAVEN SUB-EDITOR ROLF HOFMEIER LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 ISSN 1871-2525 ISBN 978-90-04-27477-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-90-04-28264-3 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents i. Preface ........................................................................................................... vii ii. List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................... ix iii. Factual Overview ........................................................................................... xiii iv. List of Authors ............................................................................................... xvii I. Sub-Saharan Africa (Andreas Mehler, -

Navy Accepts Delivery of Future USS Gravely

® Serving the Hampton Roads Navy Family Vol. 18, No. 30, Norfolk, VA FLAGSHIPNEWS.COM July 29, 2010 Navy accepts delivery of future USS Gravely BY CHRIS JOHNSON Team Ships Public Affairs WASHINGTON — The Navy offi cially ac- cepted delivery of the future USS Gravely from Northrop Grumman Shipbuilding during a ceremony, July 26, in Pascagoula, Miss. Desig- nated DDG 107, Gravely is the 57th ship of the Arleigh Burke class. The ship successfully completed acceptance trials, June 28. Due to the oil spill currently affecting the Gulf of Mexico, the trials were slightly modifi ed, with the ship conducting pierside tests and inspections by the Navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey (INSURV), fol- lowed by a 36-hour underway period to assess the ship’s main propulsion, auxiliary, steering, damage control equipment, navigation sys- tems and deck equipment as well as overall completeness. “Though the oil spill forced us to modify our normal trial schedule, we were still able to de- liver Gravely as originally scheduled,” said Capt. Pete Lyle, DDG 51 class program man- ager in the Navy’s Program Executive Offi ce (PEO) Ships. “That is really a testament to the maturity of the class and the program’s suc- cessful history of delivering ships on time and on schedule.” Gravely is a multi-mission guided-missile Photo by MC2 Corey Truax destroyer designed to operate in multi-threat The Arleigh Burke class guided-missile destroyer USS Gravely (DDG 107) is surrounded by oil containment booms to prevent oil from the air, surface and subsurface environments. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill from reaching it’s hull while pierside in Pascagoula, Miss. -

Under Attack

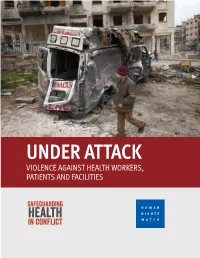

UNDER ATTACK V IOLEN CE A GA INST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Safeguarding HUMAN Health RIGHTS in Conflict WATCH (front cover) A Syrian youth walks past a destroyed ambulance in the Saif al-Dawla district of the war-torn northern city of Aleppo on January 12, 2013. © 2013 JM Lopez/AFP/Getty Images UNDER ATTACK VIOLENCE AGAINST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Overview of Recent Attacks on Health Care ...........................................................................................2 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 Urgent Actions Needed .......................................................................................................................7 Polio Vaccination Campaign Workers Killed ..........................................................................................8 Nigeria and Pakistan ......................................................................................................................8 Emergency Care Outlawed .................................................................................................................10 Turkey ..........................................................................................................................................10 Health Workers Arrested, Imprisoned ................................................................................................12 Bahrain ........................................................................................................................................12 -

Stabilizing Mali Neighbouring States´Poliitical and Military Engagement

This report aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the Stabilising Mali political and security context in which the United Nations’ stabili- sation mission in Mali, MINUSMA, operates, with a particular focus on the neighbouring states. The study seeks to identify and explain the different drivers that have led to fi ve of Mali’s neighbouring states – Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Niger and Senegal – contributing troops to MINUSMA, while two of them – Algeria and Mauretania – have decided not to. Through an analysis of the main interests and incentives that explain these states’ political and military engagement in Mali, the study also highlights how the neighbouring states could infl uence confl ict resolution in Mali. Stabilising Mali Neighbouring states’ political and military engagement Gabriella Ingerstad and Magdalena Tham Lindell FOI-R--4026--SE ISSN1650-1942 www.foi.se January 2015 Gabriella Ingerstad and Magdalena Tham Lindell Stabilising Mali Neighbouring states’ political and military engagement Bild/Cover: (UN Photo/Blagoje Grujic) FOI-R--4026--SE Titel Stabiliser ing av Mali. Grannstaters politiska och militära engagemang Title Stabilising Mali. Neighbouring states’ political and military engagement Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4026--SE Månad/Month Januari/ January Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 90 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Utrikesdepartementet/Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs Forskningsområde 8. Säkerhetspolitik Projektnr/Project no B12511 Godkänd av/Approved by Maria Lignell Jakobsson Ansvarig avdelning Försvarsanalys Detta verk är skyddat enligt lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk. All form av kopiering, översättning eller bearbetning utan medgivande är förbjuden. This work is protected under the Act on Copyright in Literary and Artistic Works (SFS 1960:729). -

Operation Serval. Analyzing the French Strategy Against Jihadists in Mali

ASPJ Africa & Francophonie - 3rd Quarter 2015 Operation Serval Analyzing the French Strategy against Jihadists in Mali LT COL STÉPHANE SPET, FRENCH AIR FORCE* imilar to the events that occurred two years earlier in Benghazi, the crews of the four Mirage 2000Ds that took off on the evening of 11 January 2013 from Chad inbound for Kona in central Mali knew that they were about to conduct a mis- sion that needed to stop the jihadist offensive to secure Bamako, the capital of Mali, and its population. This time, they were not alone because French special forces Swere already on the battlefield, ready to bring their firepower to bear. French military forces intended to prevent jihadist fighters from creating a caliphate in Mali. They also knew that suppressing any jihadist activity there would be another challenge—a more political one intended to remove the arrows from the jihadists’ hands. By answering the call for assistance from the Malian president to prevent jihadists from raiding Bamako and creating a radical Islamist state, French president François Hollande consented to engage his country in the Sahel to fight jihadists. Within a week, Operation Serval had put together a joint force that stopped the jihadist offensive and retook the initiative. Within two months, the French-led coalition had liberated the en- tire Malian territory after destruction of jihadist strongholds in the Adrar des Ifoghas by displaying a strategy that surprised both the coalition’s enemies and its allies. On 31 July 2014, this first chapter of the war on terror in the Sahel officially closed with a victory and the attainment of all objectives at that time. -

If Our Men Won't Fight, We Will"

“If our men won’t ourmen won’t “If This study is a gender based confl ict analysis of the armed con- fl ict in northern Mali. It consists of interviews with people in Mali, at both the national and local level. The overwhelming result is that its respondents are in unanimous agreement that the root fi causes of the violent confl ict in Mali are marginalization, discrimi- ght, wewill” nation and an absent government. A fact that has been exploited by the violent Islamists, through their provision of services such as health care and employment. Islamist groups have also gained support from local populations in situations of pervasive vio- lence, including sexual and gender-based violence, and they have offered to restore security in exchange for local support. Marginality serves as a place of resistance for many groups, also northern women since many of them have grievances that are linked to their limited access to public services and human rights. For these women, marginality is a site of resistance that moti- vates them to mobilise men to take up arms against an unwilling government. “If our men won’t fi ght, we will” A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Confl ict in Northern Mali Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad FOI-R--4121--SE ISSN1650-1942 November 2015 www.foi.se Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad "If our men won't fight, we will" A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Conflict in Northern Mali Bild/Cover: (Helené Lackenbauer) Titel ”If our men won’t fight, we will” Title “Om våra män inte vill strida gör vi det” Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4121—SE Månad/Month November Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 77 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Utrikes- & Försvarsdepartementen Forskningsområde 8. -

AQIM's Blueprint for Securing Control of Northern Mali

APRIL 2014 . VOL 7 . ISSUE 4 Contents Guns, Money and Prayers: FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Guns, Money and Prayers: AQIM’s Blueprint for Securing AQIM’s Blueprint for Securing Control of Northern Mali By Morten Bøås Control of Northern Mali By Morten Bøås REPORTS 6 AQIM’s Threat to Western Interests in the Sahel By Samuel L. Aronson 10 The Saudi Foreign Fighter Presence in Syria By Aaron Y. Zelin 14 Mexico’s Vigilante Militias Rout the Knights Templar Drug Cartel By Ioan Grillo 18 Drug Trafficking, Terrorism, and Civilian Self-Defense in Peru By Steven T. Zech 23 Maritime Piracy on the Rise in West Africa By Stephen Starr 26 Recent Highlights in Political Violence 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts An Islamist policeman patrolling the streets of Gao in northern Mali on July 16, 2012. - Issouf Sanogo/AFP/Getty Images l-qa`ida in the islamic As a result, even if the recent French Maghreb (AQIM) is military intervention in Mali has occasionally described as pushed back the Islamist rebels and an operational branch of the secured control of the northern cities of Aglobal al-Qa`ida structure. Yet AQIM Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu, a number of should not be viewed as an external al- challenges remain.1 The Islamists have Qa`ida force operating in the Sahel and not been defeated. Apart from the loss of Sahara. For years, AQIM and its offshoots prominent figures such as AQIM senior About the CTC Sentinel have pursued strategies of integration leader Abou Zeid and the reported death The Combating Terrorism Center is an in the region based on a sophisticated of Oumar Ould Hamaha,2 the rest of the independent educational and research reading of the local context. -

Bibliography: Boko Haram

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 13, Issue 3 Bibliography: Boko Haram Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes [Bibliographic Series of Perspectives on Terrorism – BSPT-JT-2019-5] Abstract This bibliography contains journal articles, book chapters, books, edited volumes, theses, grey literature, bibliog- raphies and other resources on the Nigerian terrorist group Boko Haram. While focusing on recent literature, the bibliography is not restricted to a particular time period and covers publications up to May 2019. The literature has been retrieved by manually browsing more than 200 core and periphery sources in the field of Terrorism Stud- ies. Additionally, full-text and reference retrieval systems have been employed to broaden the search. Keywords: bibliography, resources, literature, Boko Haram, Islamic State West Africa Province, ISWAP, Abu- bakar Shekau, Abu Musab al-Barnawi, Nigeria, Lake Chad region NB: All websites were last visited on 18.05.2019. - See also Note for the Reader at the end of this literature list. Bibliographies and other Resources Benkirane, Reda et al. (2015-): Radicalisation, violence et (in)sécurité au Sahel. URL: https://sahelradical.hy- potheses.org Bokostan (2013, February-): @BokoWatch. URL: https://twitter.com/BokoWatch Campbell, John (2019, March 1-): Nigeria Security Tracker. URL: https://www.cfr.org/nigeria/nigeria-securi- ty-tracker/p29483 Counter Extremism Project (CEP) (n.d.-): Boko Haram. (Report). URL: https://www.counterextremism.com/ threat/boko-haram Elden, Stuart (2014, June): Boko Haram – An Annotated Bibliography. Progressive Geographies. URL: https:// progressivegeographies.com/resources/boko-haram-an-annotated-bibliography Hoffendahl, Christine (2014, December): Auf der Suche nach einer Strategie gegen Boko Haram. [In search for a strategy against Boko Haram]. -

2/2013 Misadventure Or Mediation in Mali: the EU’S Potential Role by Paul Pryce

cejiss 2/2013 Misadventure or Mediation in Mali: The EU’s Potential Role By Paul Pryce With a humanitarian crisis mounting in the West African state of Mali, the Council of the European Union has called on the Economic Community of West African States to deploy a stabilisation force to the northern regions of the country. But such a military intervention would have to contend with a plethora of cultural and logistical chal- lenges. A better approach might be for the Council to appoint an EU Special Representative for the Sahel Region, employing the Union’s ci- vilian power to facilitate mediation between the central government in Mali and the Tuareg rebel groups that recently proclaimed a de facto independent state in the north, the Islamic Republic of Azawad. Keywords: European Union, Mali, ECOWAS, conflict prevention, Tu- areg Introduction On 23 July 2012, the Council of the European Union convened in Brussels to discuss a number of issues relating to the EU’s external af- fairs. In a statement released at the conclusion of those proceedings, the Council expressed its concern over the deteriorating situation in Mali and called on the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to deploy a stabilisation force to the country.1 This expres- sion of support for military intervention from the EU Member States comes shortly after calls were issued by some in the American press, such as the Editorial Board of the Washington Post, for NATO to act militarily to stabilize Mali.2 22 However, the Council may have been too hasty in offering its sup- port for the deployment of such an ECOWAS stabilisation force. -

French Defence Policy in a Time of Uncertainties Yves Boyer

FOKUS | 5/2012 French defence policy in a time of uncertainties Yves Boyer Besides the United States the EU is the reasons (historical, societal, diplomatic, In the military domains the French only grouping of nations able to project etc.) explain the many difficulties met by defence organisation, whatever its limits, its influence worldwide. Despite the the Europeans to further their cooperation has been organised to be efficient and current crisis, the EU remains a global in that field and the various ambiguities in to maintain the coherence of the French economic superpower with the highest the conduct of each EU country’s defence defence posture. The Executive (the Pre- GNP worldwide when the various GNP affairs. sident of the Republic) is the head of the of its members are combined. In the armed forces according to the constitu- foreseeable future this situation will be France shares with her EU’s partners, tion. He provides guidance (subsequently preserved, allowing the Union to generate and notably those members of the agreed on by the Parliament) on the financial surpluses which can be used to Eurozone, the dire effects of the financial overall strategy and military organisati- back its policy of global influence based and economic crisis. The debt issue, in on. He carefully controlls their execution on diverse forms of “civilian” power with conjunction with economic stagnation, through his military staff at the Elysée a central position in various international will affect public spending and, notably, palace and directs their implementation networks and a significant role in interna- defence expenditure. However, France through the chairing of the high council tional institutions.