Africa Yearbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Banjo.Pmd 69 05/09/2007, 11:09 70 Africa Development, Vol

Africa Development, Vol. XXXII, No. 1, 2007, pp.69–87 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2007 (ISSN 0850-3907) The ECOWAS Court and the Politics of Access to Justice in West Africa Adewale Banjo* Abstract Although the creation of the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice (ECJ) was approved in 1991 in pursuant to the provisions of Articles 6 and 15 of the 1993 Revised Treaty of the Economic Community of West African States, it was only set up a decade later in 2001. By utilising a content-analysis method, in addition to extensive personal interviews with the President of the Court, this study describes the emergence, composition, vision and competence/jurisdiction of the ECJ. The paper probes the various challenges currently faced by the ECJ, which include among others, logistics, limited public awareness among ECOWAS citizens, and non use by member states. The inability of ECOWAS citizens to access justice is given prominent emphasis with reference to the case of Afolabi Olajide vs. Federal Republic of Nigeria. The case typifies the extent to which the ECJ’s establishment fulfilled or failed to meet the expectation of ECOWAS citi- zens’ quest for justice. The study’s conclusion examines current efforts at broad- ening access to the court for citizens of the community. Résumé Bien que la Cour de Justice Communautaire de la Cedeao ait été approuvée depuis 1991, elle n’a été mise en place qu’en 2001 – c’est-à-dire une décennie plus tard. Sa création fait suite aux dispositions des Articles 6 et 15 du Traité Révisé de la Communauté économique des États de l’Afrique de l’Ouest de 1993. -

ECOWAS Commission Strategic Plan

WITHOUT PICTORIALS Strategic Plan: 2011- 2015 ECOWAS CEDEAO There is nothing we have achieved as a A PROACTIVE MECHANISM region and there is no challenge yet to come, that we can overcome FOR CHANGE without a strategic look into the future through a proactive mechanism of change and strategic planning of goals and objectives. The process is not only defining the strategy, or direction, but also making decisions on resource allocation to pursue this strategy, including its capital and people. REGIONAL STRATEGIC PLAN (2011 – 2015)1 Strategic Plan: 2011- 2015 ECOWAS CEDEAO Document Authorization Document purpose This document describes a coherent short-medium term rolling plan for the implementation of regional programs by ECOWAS Institutions and other stakeholders. It derives directly from the Long-Term Vision of ECOWAS, the ECOWAS Vision 2020. Distribution control Version Number: 1.0 Copyright owner This document is owned by ECOWAS Commission, the front office of ECOWAS Document Authorization Chairman, Council of Ministers of ECOWAS Signature:---------------------------------------------------------------------------- President, ECOWAS Commission Signature:---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Release 2 Strategic Plan: 2011- 2015 ECOWAS CEDEAO Content A Strategic Plan for the future of ECOWAS Acronyms and Abbreviations Foreword Preface Executive Summary 1. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) 1.1 Background 1.2 Institution and Policy Development Process 1.3 Institutional Capacity 1.4 Achievements to Date 2. ECOWAS Vision 2020 2.1 Restatement of the ECOWAS Vision 2.2 Mission Statement of ECOWAS Institutions 2.3 Core Values of ECOWAS Institutions 2.4 Co-ordination, Collaboration and Co-operation 3. ECOWAS Strategic Plan 3.1 Purpose of the Regional Strategic Plan 3.2 Ground Rules 4. -

Nigerian Foreign Policy: a Fourth Republic Diplomatic Escapade

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 4 (2016 9) 708-721 ~ ~ ~ УДК 323.3(669) Nigerian Foreign Policy: a Fourth Republic Diplomatic Escapade Ebenezer Ejalonibu Lawala and Opeyemi Idowu Alukob* aFederal University Lokoja Kogi State Nigeria bUniversity of Ilorin Kwara State Nigeria Received 14.11.2015, received in revised form 02.12.2015, accepted 19.03.2016 Foreign policy is unpredictable and has no specific domestic or international boundary. The scope is not static; issues in foreign policy are continuous. Therefore, no government consciously design her foreign policy outlook, the focus of any foreign policy would depend heavily on events in and around the nation and Nigeria is not an exception. The concept of Africa as the centre-piece of Nigerian’s foreign policy has emerged as the most consistent theme that runs through her foreign policies in all the various regimes. Foreign policy of Nigeria could be called a three concentric circle, this concentric circle clearly puts Nigeria’s interest first, West African Sub-region second and then the rest of Africa. It is very crucial to note that between 1960 and 1990, eighteen civil wars in Africa resulted in about 7 million deaths and spawned 5 million refugees. Nigeria cannot ignore Africa’s problems rather she must maintain the principle of Afrocentrism. This is so because; one out of every five Africans is a Nigerian. This paper therefore seeks to critically analyze the core issues in Nigerian foreign policy and challenges facing Nigerian foreign policy in the fourth republic, some recommendations will also be suggested. Keywords: Foreign Policy, Diplomacy, United Nation, Africa and Nigeria. -

TEMPERED LIKE STEEL the Economic Community of West African States Celebrated Its 30Th Anniversary in May, 2005

ECOWAS 30th anniversary and roughly for the same reasons: economic cooperation among of the 15 members have met the economic convergence criteria. member states and collective bargaining strength on a global level. However, it is an instrument whose time has come and it seems cer- Ecowas was an acknowledgement that despite all their differ- tain that the Eco will make its appearance in the near future. ences, the member states were essentially the same in terms of needs, One of Ecowas’ successes has been in allowing relatively free resources and aspirations. It was also an acknowledgement that the movement of people across borders. Passports or national identity integration of their relative small markets into a large regional one documents are still required but not visas. Senegal and Benin issue was essential to accelerate economic activity and therefore growth. Ecowas passports to their citizens. The founders of the organisation were just as convinced that artifi- The Ecowas Secretariat in Abuja is working on modalities to allow cial national barriers, created on old colonial maps, were cutting across document-free movement of people and goods. This might take time, ancient trade routes and patterns and that these barriers had to go. as other regulations, such as residence and establishment rights have However, this came about at a time when sub-regional organisa- to be put in place first. tions were looked on with a degree of suspicion and African coun- One of the organisation's most vital arms is Ecomog, its peace- tries, encouraged by Cold War politics, had become inward-looking keeping force. -

BTI 2018 Country Report Liberia

BTI 2018 Country Report Liberia This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Liberia. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Liberia 3 Key Indicators Population M 4.6 HDI 0.427 GDP p.c., PPP $ 813 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 2.5 HDI rank of 188 177 Gini Index 33.2 Life expectancy years 62.0 UN Education Index 0.454 Poverty3 % 73.8 Urban population % 50.1 Gender inequality2 0.649 Aid per capita $ 243.2 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Liberia’s development has been broadly positive. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Allenson 1 Clare Allenson Global Political Economy Honors Capstone Word Count: 8,914 April 14, 2009 the Evolution of Economic I

Allenson 1 Clare Allenson Global Political Economy Honors Capstone Word Count: 8,914 April 14, 2009 The Evolution of Economic Integration in ECOWAS I. Introduction Since gaining political independence in the 1960s, African leaders have consistently reaffirmed their desire to forge mutually beneficial economic and political linkages in order to enhance the social and economic development of Africa’s people. Their desire to achieve greater economic integration of the continent has led to the “‘creation of the most extensive network of regional organizations anywhere in the world 1.’” Regional networks in Africa are not a recent phenomenon, but have an historic roots as the historian Stanislas Adotevi states that “those who deny that Africans have much to trade among themselves ignore the history of precolonial trade, which was based on the exchange of good across different ecological zones, in a dynamic regional trading system centered on the entrepot markets that sprang up at the interstices of these zones 2.” He argues that colonialism disrupted these linkages that could have resulted in commercial centers of regional integration. These historical networks were rekindled in 1975, when fifteen nations, mostly former British and French colonies formed the regional organization, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) with the objective of increasing regional trade, improving free movement of labor, and developing policy harmonization 3. Throughout the 1980s the regional community struggled to create a coherent policy of integration until the early 1990s, when political cooperation increased as a result of a joint 1 Buthelezi, xiv 2 Lavergne, 72 3 Ibid, 133 Allenson 2 regional peacekeeping operation in Liberia and in 1993, member states signed a revised treaty with the goal of accelerating integration. -

Under Attack

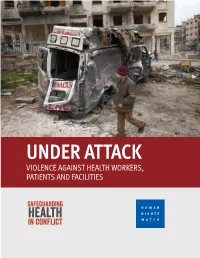

UNDER ATTACK V IOLEN CE A GA INST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Safeguarding HUMAN Health RIGHTS in Conflict WATCH (front cover) A Syrian youth walks past a destroyed ambulance in the Saif al-Dawla district of the war-torn northern city of Aleppo on January 12, 2013. © 2013 JM Lopez/AFP/Getty Images UNDER ATTACK VIOLENCE AGAINST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Overview of Recent Attacks on Health Care ...........................................................................................2 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 Urgent Actions Needed .......................................................................................................................7 Polio Vaccination Campaign Workers Killed ..........................................................................................8 Nigeria and Pakistan ......................................................................................................................8 Emergency Care Outlawed .................................................................................................................10 Turkey ..........................................................................................................................................10 Health Workers Arrested, Imprisoned ................................................................................................12 Bahrain ........................................................................................................................................12 -

Governance Transfer by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

Governance Transfer by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) A B2 Case Study Report Christof Hartmann SFB-Governance Working Paper Series • No. 47 • December 2013 DFG Sonderforschungsbereich 700 Governance in Räumen begrenzter Staatlichkeit - Neue Formen des Regierens? DFG Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 700 Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood - New Modes of Governance? SFB-Governance Working Paper Series Edited by the Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 700 “Governance In Areas of Limited Statehood - New Modes of Gover- nance?” The SFB-Governance Working Paper Series serves to disseminate the research results of work in progress prior to publication to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the Working Paper Series should not limit publication in any other venue. Copyright remains with the authors. Copyright for this issue: Christof Hartmann Editorial assistance and production: Clara Jütte/Ruth Baumgartl/Sophie Perl All SFB-Governance Working Papers can be downloaded free of charge from www.sfb-governance.de/en/publikationen or ordered in print via e-mail to [email protected]. Christof Hartmann 2013: Governance Transfer by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). A B2 Case Study Report, SFB-Governance Working Paper Series, No. 47, Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 700, Berlin, December 2013. ISSN 1864-1024 (Internet) ISSN 1863-6896 (Print) This publication has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). DFG Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 700 Freie Universität Berlin Alfried-Krupp-Haus Berlin Binger Straße 40 14197 Berlin Germany Phone: +49-30-838 58502 Fax: +49-30-838 58540 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.sfb-governance.de/en SFB-Governance Working Paper Series • No. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms international A Ben & Howell information Company 300 North Z eeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 40106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 INSTITUTIONAL REFORM OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS IN SENEGAL, MALI AND GHANA: THE INTERPLAY OF STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT AND INTERNATIONAL POLICY DIFFUSION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Cheikh Tidiane Gadio, Licence, Maltrise, D.E.A. -

Conflict Analysis of Liberia

Conflict analysis of Liberia February 2014 Siân Herbert About this report This rapid review provides a short synthesis of the literature on conflict and peace in Liberia. It aims to orient policymakers to the key debates and emerging issues. It was prepared for the European Commission’s Instrument for Stability, © European Union 2014. The views expressed in this report are those of the author, and do not represent the opinions or views of the European Union, the GSDRC, or the partner agencies of the GSDRC. The author extends thanks to Dr Mats Utas (The Nordic Africa Institute), who acted as consultant and peer reviewer for this report. Expert contributors Dr Thomas Jaye (Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre) Diego Osorio (former United Nations Mission in Liberia) Dr Sukanya Podder (Cranfield University) Dr Alexander Ramsbotham (Conciliation Resources) Eric Werker (Harvard Business School) Craig Lamberton (USAID) Julia Escalona (USAID) Tiana Martin (USAID) Suggested citation Herbert, S. (2014). Conflict analysis of Liberia. Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham. About GSDRC GSDRC is a partnership of research institutes, think-tanks and consultancy organisations with expertise in governance, social development, humanitarian and conflict issues. We provide applied knowledge services on demand and online. Our specialist research team supports a range of international development agencies, synthesising the latest evidence and expert thinking to inform policy and practice. GSDRC, International Development Department, College of Social Sciences University of Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK www.gsdrc.org [email protected] Conflict analysis of Liberia Contents 1. Overview 1 2. Conflict and violence profile 2 3. Principal domestic actors 4 3.1 Political personalities and parties 3.2 Principal security actors 3.3 Ex-combatants and ex-commanders 3.4 Civil society organisations 4. -

If Our Men Won't Fight, We Will"

“If our men won’t ourmen won’t “If This study is a gender based confl ict analysis of the armed con- fl ict in northern Mali. It consists of interviews with people in Mali, at both the national and local level. The overwhelming result is that its respondents are in unanimous agreement that the root fi causes of the violent confl ict in Mali are marginalization, discrimi- ght, wewill” nation and an absent government. A fact that has been exploited by the violent Islamists, through their provision of services such as health care and employment. Islamist groups have also gained support from local populations in situations of pervasive vio- lence, including sexual and gender-based violence, and they have offered to restore security in exchange for local support. Marginality serves as a place of resistance for many groups, also northern women since many of them have grievances that are linked to their limited access to public services and human rights. For these women, marginality is a site of resistance that moti- vates them to mobilise men to take up arms against an unwilling government. “If our men won’t fi ght, we will” A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Confl ict in Northern Mali Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad FOI-R--4121--SE ISSN1650-1942 November 2015 www.foi.se Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad "If our men won't fight, we will" A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Conflict in Northern Mali Bild/Cover: (Helené Lackenbauer) Titel ”If our men won’t fight, we will” Title “Om våra män inte vill strida gör vi det” Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4121—SE Månad/Month November Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 77 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Utrikes- & Försvarsdepartementen Forskningsområde 8.