Report of the Panel of Experts on Liberia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberia BULLETIN Bimonthly Published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Liberia

LibeRIA BULLETIN Bimonthly published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Liberia 1 October 2004 Vol. 1, Issue No. 4 Voluntary Repatriation Started October 1, 2004 The inaugural convoys of 77 Liberian refugees from Sierra Leone and 97 from Ghana arrived to Liberia on October 1, 2004, which marked the commencement of the UNHCR voluntary repatriation. Only two weeks prior to the beginning of the repatriation, the County Resettlement Assessment Committee (CRAC) pro- claimed four counties safe for return – Grand Cape Mount, Bomi, Gbarpolu and Margibi. The first group of refugees from Sierra Leone is returning to their homes in Grand Cape Mount. UNHCR is only facilitating re- turns to safe areas. Upon arrival, returnees have the option to spend a couple of nights in transit centers (TC) before returning to their areas of origin. At the TC, they received water, cooked meals, health care, as well as a two-months resettlement ration and a Non- Signing of Tripartite Agreement with Guinea Food Items (NFI) package. With the signing of the Tripartite Agreements, which took place in Accra, Ghana, on September 22, 2004 with the Ghanian government and in Monrovia, Liberia, on September 27, 2004 with the governments of Si- erra Leone, Guinea and Cote d’Ivorie, binding agree- ment has been established between UNHCR, asylum countries and Liberia. WFP and UNHCR held a regional meeting on Septem- ber 27, 2004 in Monrovia and discussed repatriation plans for Liberian refugees and IDPs. WFP explained that despite the current food pipeline constraints, the repatriation of refugees remains a priority for the Country Office. -

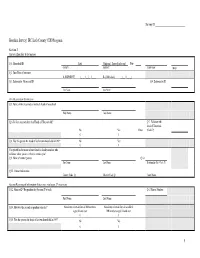

Baseline Survey | IRC/Lofa County CDD Program

Survey ID _________________________ Baseline Survey | IRC/Lofa County CDD Program Section I Survey Identifier Information Q 1. Household ID: Lofa Voinjama | Zorzor [circle one] PA#: COUNTY DISTRICT TOWN NAME HH # Q 2. Date/Time of Interview: A. (DD/MM/YY) |__|__|/|__|__|/|__|__| B. (24 hr clock) |__|__| : |__|__| Q 3. Enumerator Name and ID: Q 4. Enumerator ID First Name Last Name First Respondent Information Q 5. Name of First respondent (normally head of household) First Name Last Name Q 6. Is first respondent the Head of Household? Q 7. Relation with head of Househod: No Yes If not: (Code P) 0 1 Q 8. Was this person the head of his/her own household in 1989? No Yes 0 1 Can you tell us the name of one friend or family member who will know where you are or how to contact you? Q 9. Name of contact person Q 10 First Name Last Name Relationship [Use Code P] Q 11. Contact Information County Code Q _____ _____ District Code Q ____ ____ ____ ____ Town Name ______________________________ Second Respondent Information (Enter once you begin 2nd interview) Q 12. Name of 2nd Respondent for (Section IV to end): Q 13 Roster Number: First Name Last Name Q 14. How was the second respondent selected? Randomly selected from all HH members Randomly selected from all available aged 18 and over HH members aged 18 and over 0 1 Q 15. Was this person the head of his own household in 1989? No Yes 0 1 1 Survey ID _________________________ II Pre War and Post War Household Roster I want you to think about your household today. -

Sexual Gender-Based Violence and Health Facility Needs Assessment

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION SEXUAL GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE AND HEALTH FACILITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT (LOFA, NIMBA, GRAND GEDEH AND GRAND BASSA COUNTIES) LIBERIA By PROF. MARIE-CLAIRE O. OMANYONDO RN., Ph.D SGBV CONSULTANT DATE: SEPTEMBER 9 - 29, 2005 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AFELL Association of Female Lawyers of Liberia HRW Human Rights Watch IDP Internally Displaced People IRC International Rescue Committee LUWE Liberian United Women Empowerment MSF Medecins Sans Frontières NATPAH National Association on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Womn and Children NGO Non-Governmental Organization PEP Post-Exposure Prophylaxis PTSD Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder RHRC Reproductive Health Response in Conflict SGBV Sexual Gender-Based Violence STI Sexually Transmitted Infection UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund WFP World Food Programme WHO World Health Organization 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Problem Statement 1.1. Research Question 1.2. Objectives II. Review of Literature 2.1. Definition of Concepts 2.2. Types of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence 2.3. Consequences of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence 2.4. Sexual and Gender-Based Violence III. Methodology 3.1 Sample 3.2 3.3 Limitation IV. Results and Discussion A. Community Assessment results A.1. Socio-Demographic characteristics of the Respondents A.1.a. Age A.1.b. Education A.1.c. Religious Affiliation A.1.d. Ethnic Affiliation A.1.e. Parity A.1.f. Marital Status A.2. Variables related to the study 3 A.2.1. Types of Sexual Violence A.2.2. Informing somebody about the incident Reaction of people you told A.2.3. Consequences of Sexual and Gender Based Violence experienced by the respondents A.2.3.1. -

BTI 2018 Country Report Liberia

BTI 2018 Country Report Liberia This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Liberia. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Liberia 3 Key Indicators Population M 4.6 HDI 0.427 GDP p.c., PPP $ 813 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 2.5 HDI rank of 188 177 Gini Index 33.2 Life expectancy years 62.0 UN Education Index 0.454 Poverty3 % 73.8 Urban population % 50.1 Gender inequality2 0.649 Aid per capita $ 243.2 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Liberia’s development has been broadly positive. -

President Richard Nixon's Daily Diary, July 16-31, 1969

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest 7/30/1969 A 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest from Don- 7/30/1969 A Maung Airport, Bangkok 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/23/1969 A Appendix “B” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/24/1969 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/26/1969 A Appendix “B” 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/27/1969 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-3 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary July 16, 1969 – July 31, 1969 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) rnc.~IIJc.I'" rtIl."I'\ttU 1"'AUI'4'~ UAILJ UIAtU (See Travel Record for Travel Activity) ---- -~-------------------~--------------I PLACi-· DAY BEGA;'{ DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) JULY 16, 1969 TIME DAY THE WHITE HOUSE - Washington, D. -

A Positive Africa

A POSITIVE AFRICA AHAVI PRESENTATION 2011 • “UNTIL THE LION HAS HIS OWN HISTORIAN, THE HUNTER WILL ALWAYS BE A HERO.” -- African Proverb DID YOU KNOW THAT AFRICA IS NOT ONE COUNTRY? DID YOU KNOW THAT AFRICANS HAD CLOTHES BEFORE EUROPEAN CONTACT? TWO NIGERIAN WOMEN IN TRADTIONAL CLOTHES INDIGO CLOTH, NIGERIA A NORTHERN NIGERIAN GIRL IN TRADITIONAL CLOTHES EX- PRESIDENT OF GHANA WEARING INDIGENOUS CLOTH, KENTE TRADITIONAL MEN’S CLOTHES: GHANA AN ELDERLY GHANAIAN WOMAN IN KENTE CLOTH DANCING GHANAIAN GIRLS IN KENTE CLOTH DANCING GHANAIAN WOMAN IN A LOCAL ATIRE GHANAIANS DRESSED IN OTHER LOCAL CLOTHES: A QUEEN IN THE MIDDLE ADINKRA CLOTH OF GHANA & COTE D’IVOIRE BUBU CLOTHES OF WEST AFRICA MOTHER AND SON DRESSED IN TRADITIONAL GHANAIAN CLOTHES WOMEN IN CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN CLOTHES BOOKSLEEVE BUTTERFLY LOVE KNOTS TULIP FASHION AFRICAN STYLE MODELING AFRICAN FASHION NIGERIAN WOMAN IN TRADITIONAL HEAD BAND GOING TO A WEDDING AFRICAN STYLE WHERE ARE THE TREE HOUSES OF AFRICA? DID YOU KNOW THAT AFRICANS LIVED IN HOUSES BEFORE EUROPEAN CONTACT? The Gurunsi architecture in Ghana and Burkina Faso, known for the beauty of its functional lines, inspired the Swiss vanguard architect Le Corbusier HATA VILLAGE MORE GURUNSI ARCHITECTURE DRAA VALLEY CASBA, MOROCCO GREAT ZIMBABWE CARVED ENTRANCE TO THE PALACE OF THE EMIR IN KANO, NIGERIA AFRICA’S UNDERGROUND TOWNS • During their long war with Ethiopia, the Eritrean soldiers lay low by building amazing underground towns where they could make weapons and tend to their wounded without being spotted by the Ethiopian army. AFRICAN UNIVERSITIES BEFORE COLONIZATION THE GREAT UNIVERSITY OF SANKORE AT TIMBUKTU TIMBUKTU: A UNIVERSITY TOWN IN PRE-COLONIAL WEST AFRICA "Until the lion has his historian, the hunter will always be a hero." --African Proverb Timbuktu was more than merely a great intellectual nucleus of the West African civilizations of Ghana, Mali and Songhai--it was one of the most splendid scientific centers of the time period corresponding to the European Medieval and Renaissance eras. -

Africa Yearbook

AFRICA YEARBOOK AFRICA YEARBOOK Volume 10 Politics, Economy and Society South of the Sahara in 2013 EDITED BY ANDREAS MEHLER HENNING MELBER KLAAS VAN WALRAVEN SUB-EDITOR ROLF HOFMEIER LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 ISSN 1871-2525 ISBN 978-90-04-27477-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-90-04-28264-3 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents i. Preface ........................................................................................................... vii ii. List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................... ix iii. Factual Overview ........................................................................................... xiii iv. List of Authors ............................................................................................... xvii I. Sub-Saharan Africa (Andreas Mehler, -

River Gee County Development Agenda

River Gee County Development Agenda Republic of Liberia 2008 – 2012 River Gee County Development Agenda bong County Vision Statement River Gee: a unified, peaceful and well-governed County with robust socio-economic and infrastructure development for all. Core Values Building on our core competencies and values, we have a mission to support Equal access to opportunities for all River Gee Citizens; Assurance of peace, security and the rule of law; Transparent and effective governance; Sustainable economic growth; and Preservation of natural resources and environment. Republic of Liberia Prepared by the County Development Committee, in collaboration with the Ministries of Planning and Economic Affairs and Internal Affairs. Supported by the UN County Support Team project, funded by the Swedish Government and UNDP. Table of Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS........! iii FOREWORD..........................................................................! iv PREFACE!!............................................................................. vi RIVER GEE COUNTY OFFICIALS............................................! vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................! ix PART ONE - INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1.!Introduction................................................................................................! 1 1.2.!History........................................................................................................! 1 1.3.!Geography..................................................................................................! -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Transcript of Interview with H.E. President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Moderated by Mr

Transcript of Interview with H.E. President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Moderated by Mr. Darryl Ambrose Nmah, Director General, Liberia Broadcasting System On the Super Morning Show Held at the Studios of the Liberia Broadcasting System, Paynesville Monday, July 1, 2013 President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf: I am pleased to be here; good morning to all. DG Nmah: Let me just inform you, Madam President, that by kind courtesy of our partners, this interview is also heard by Liberians across the world. So, if you are there, its www.globalafricradio.com. So, maybe you have a special message for Liberians who are not in the country and are in the Diaspora, this morning. You want to greet them? President Sirleaf: Absolutely. I’d like to say to them that we are thankful to all that they do to support the country through remittances, through connections with their families and their institutions, and we’re just looking forward to many of them who are coming home, even if for just short periods of time, and we hope some of them will think about relocating and joining the process of reconstruction. DG Nmah: Well, that says it for you out there. I’m sure most of you are keen on following – Gerald promised to wake up most of the Liberians in the United States – but those of you in the UK and other parts of Europe who have already started hitting us on the website, you know that the interview is on. Madam President, it’s quite a while, you’ve recently been out in Abuja, Nigeria; before then, you were out in Washington, in New York, in Japan and in Addis. -

Final RREA Breaks Ground for 40Km Road Project in Lofa.19.09.18.Pdf

Rural and Renewable Energy Agency Newport Street, Monrovia Rural & Renewable Energy Agency (RREA) breaks ground for construction and rehabilitation of access roads leading to the proposed Kaiha 2 Hydropower Site, Lukambeh District, Lofa County Voinjama Sept. 6: The Rural and Renewable Energy Agency (RREA) on September 5, 2018, broke grounds for the construction of a 5.5 kilometer road from Mbaloma to the proposed Kaiha 2 Hydropower Sites in Lukambeh District, Lofa County. This ground breaking activity also includes plans for the rehabilitation of the 35 kilometer road that links Mbaloma to Kolahun- Foya Junction. The event brought together local County officials headed by Honorable William Tamba Kamba, Superintendent of Lofa County, officials from the RREA, citizens of the District, and representatives of SSF Entrepreneurs, the road contractor. RREA Executive Director Augustus V. Goanue participates in the ground breaking ceremony The road project is part of the implementation of a $27 million project entitled Liberia Renewable Energy Access Project (LIRENAP), agreed between the World Bank and the Government of Liberia, which is aimed at increasing access to electricity and to foster the use of renewable energy sources, Page 1 of 4 thereby, reducing poverty and boosting shared prosperity. The LIRENAP project will finance the construction of a 2.5 MW mini-hydropower plant, the supply and installation of a 1.8 MW diesel generation plant, as well as transmission and distribution facilities that is expected to connect about 50,000 beneficiaries in major population centers in Lofa County, including Voinjama, Foya, Kolahun, Massambolahun, Bolahun and surrounding small towns and villages. -

Conflict Analysis of Liberia

Conflict analysis of Liberia February 2014 Siân Herbert About this report This rapid review provides a short synthesis of the literature on conflict and peace in Liberia. It aims to orient policymakers to the key debates and emerging issues. It was prepared for the European Commission’s Instrument for Stability, © European Union 2014. The views expressed in this report are those of the author, and do not represent the opinions or views of the European Union, the GSDRC, or the partner agencies of the GSDRC. The author extends thanks to Dr Mats Utas (The Nordic Africa Institute), who acted as consultant and peer reviewer for this report. Expert contributors Dr Thomas Jaye (Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre) Diego Osorio (former United Nations Mission in Liberia) Dr Sukanya Podder (Cranfield University) Dr Alexander Ramsbotham (Conciliation Resources) Eric Werker (Harvard Business School) Craig Lamberton (USAID) Julia Escalona (USAID) Tiana Martin (USAID) Suggested citation Herbert, S. (2014). Conflict analysis of Liberia. Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham. About GSDRC GSDRC is a partnership of research institutes, think-tanks and consultancy organisations with expertise in governance, social development, humanitarian and conflict issues. We provide applied knowledge services on demand and online. Our specialist research team supports a range of international development agencies, synthesising the latest evidence and expert thinking to inform policy and practice. GSDRC, International Development Department, College of Social Sciences University of Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK www.gsdrc.org [email protected] Conflict analysis of Liberia Contents 1. Overview 1 2. Conflict and violence profile 2 3. Principal domestic actors 4 3.1 Political personalities and parties 3.2 Principal security actors 3.3 Ex-combatants and ex-commanders 3.4 Civil society organisations 4.