Sexual Gender-Based Violence and Health Facility Needs Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberia BULLETIN Bimonthly Published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Liberia

LibeRIA BULLETIN Bimonthly published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Liberia 1 October 2004 Vol. 1, Issue No. 4 Voluntary Repatriation Started October 1, 2004 The inaugural convoys of 77 Liberian refugees from Sierra Leone and 97 from Ghana arrived to Liberia on October 1, 2004, which marked the commencement of the UNHCR voluntary repatriation. Only two weeks prior to the beginning of the repatriation, the County Resettlement Assessment Committee (CRAC) pro- claimed four counties safe for return – Grand Cape Mount, Bomi, Gbarpolu and Margibi. The first group of refugees from Sierra Leone is returning to their homes in Grand Cape Mount. UNHCR is only facilitating re- turns to safe areas. Upon arrival, returnees have the option to spend a couple of nights in transit centers (TC) before returning to their areas of origin. At the TC, they received water, cooked meals, health care, as well as a two-months resettlement ration and a Non- Signing of Tripartite Agreement with Guinea Food Items (NFI) package. With the signing of the Tripartite Agreements, which took place in Accra, Ghana, on September 22, 2004 with the Ghanian government and in Monrovia, Liberia, on September 27, 2004 with the governments of Si- erra Leone, Guinea and Cote d’Ivorie, binding agree- ment has been established between UNHCR, asylum countries and Liberia. WFP and UNHCR held a regional meeting on Septem- ber 27, 2004 in Monrovia and discussed repatriation plans for Liberian refugees and IDPs. WFP explained that despite the current food pipeline constraints, the repatriation of refugees remains a priority for the Country Office. -

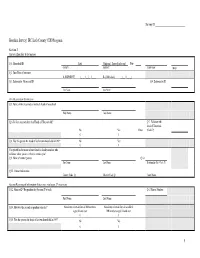

Baseline Survey | IRC/Lofa County CDD Program

Survey ID _________________________ Baseline Survey | IRC/Lofa County CDD Program Section I Survey Identifier Information Q 1. Household ID: Lofa Voinjama | Zorzor [circle one] PA#: COUNTY DISTRICT TOWN NAME HH # Q 2. Date/Time of Interview: A. (DD/MM/YY) |__|__|/|__|__|/|__|__| B. (24 hr clock) |__|__| : |__|__| Q 3. Enumerator Name and ID: Q 4. Enumerator ID First Name Last Name First Respondent Information Q 5. Name of First respondent (normally head of household) First Name Last Name Q 6. Is first respondent the Head of Household? Q 7. Relation with head of Househod: No Yes If not: (Code P) 0 1 Q 8. Was this person the head of his/her own household in 1989? No Yes 0 1 Can you tell us the name of one friend or family member who will know where you are or how to contact you? Q 9. Name of contact person Q 10 First Name Last Name Relationship [Use Code P] Q 11. Contact Information County Code Q _____ _____ District Code Q ____ ____ ____ ____ Town Name ______________________________ Second Respondent Information (Enter once you begin 2nd interview) Q 12. Name of 2nd Respondent for (Section IV to end): Q 13 Roster Number: First Name Last Name Q 14. How was the second respondent selected? Randomly selected from all HH members Randomly selected from all available aged 18 and over HH members aged 18 and over 0 1 Q 15. Was this person the head of his own household in 1989? No Yes 0 1 1 Survey ID _________________________ II Pre War and Post War Household Roster I want you to think about your household today. -

River Gee County Development Agenda

River Gee County Development Agenda Republic of Liberia 2008 – 2012 River Gee County Development Agenda bong County Vision Statement River Gee: a unified, peaceful and well-governed County with robust socio-economic and infrastructure development for all. Core Values Building on our core competencies and values, we have a mission to support Equal access to opportunities for all River Gee Citizens; Assurance of peace, security and the rule of law; Transparent and effective governance; Sustainable economic growth; and Preservation of natural resources and environment. Republic of Liberia Prepared by the County Development Committee, in collaboration with the Ministries of Planning and Economic Affairs and Internal Affairs. Supported by the UN County Support Team project, funded by the Swedish Government and UNDP. Table of Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS........! iii FOREWORD..........................................................................! iv PREFACE!!............................................................................. vi RIVER GEE COUNTY OFFICIALS............................................! vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................! ix PART ONE - INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1.!Introduction................................................................................................! 1 1.2.!History........................................................................................................! 1 1.3.!Geography..................................................................................................! -

Appeal E-Mail: [email protected]

150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Tel: 41 22 791 6033 Fax: 41 22 791 6506 Appeal e-mail: [email protected] Coordinating Office Liberia Assistance to IDPs and Returnees - AFLR11 Appeal Target: US$ 297,628 Geneva, March 30, 2001 Dear Colleagues, The fighting in Liberia’s Kolahun District in Lofa between the Liberian Government troops and the rebels have caused great suffering to tens of thousands of people and responsible for the destruction of infrastructures including private homes, public buildings, schools, hospitals and clinics. The belligerents in the war have destroyed and looted homes and responsible for a number of people who have been killed. In addition to the 20,000 people who were displaced in the October, 2000 fighting another over 5,000 people have been displaced in the latest fighting this February, and have taken refugee in the districts of Kongba, Gbarma and Tubmanburg city in Bomi county. Lutheran World Federation / World Service (LWF/WS) proposes to assist IDPs in Lofa and Bomi Counties, affected by the current hostilities especially in the district of Salayea. Special attention will be given to the internally displaced numbering 25,000. The assistance will include: · Food distribution · Non Food Items (mainly blankets, and clothes) · Health (Support to Clinics) · Water & Sanitation · Seeds and Tools ACT is a worldwide network of churches and related agencies meeting human need through coordinated emergency response. The ACT Coordinating Office is based with the World Council of Churches (WCC) -

Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone

Special mVAM Regional Bulletin #2: December 2014 Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone In spite of seasonal declines, negative coping remains high in areas exposed to EVD WFP/ Fabio Bedini Fabio WFP/ Tracking food security during the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak Fighting Hunger Worldwide Highlights Households are continuing to rely on high levels of negative coping mechanisms in Kailahun, Sierra Leone, and in Lofa County, Liberia – areas that were food-secure before the crisis. Ebola-induced food insecurity remains a serious concern. In the Nzerekore Region of Guinea and in the central zone of Liberia, households are using fewer negative coping strategies compared to November. In other zones, levels of negative coping strategies have remained constant over the past month. Generally, local rice prices are in seasonal decline and imported rice prices are stable or falling. Palm oil prices are stable or increasing in Liberia as markets resume, but they are falling in Sierra Leone, contrary to usual seasonal trends. While wage-to-rice terms of trade are improving in most areas of Guinea and in southern and eastern Sierra Leone, they are declining in Liberia and in areas of Sierra Leone that are experiencing continued EVD transmission. Source: WFP mVAM EVD incidences remain intense in Sierra Leone In Sierra Leone, EVD incidence rates remain intense. Freetown, the capital, continues to be the worst-affected area, however incidence rates remain high in much of the country, except for the south. Table 1: Reported new incidences of EVD In Guinea, incidences of EVD have been increasing slightly since early October, with between 75 and 148 new confirmed cases Guinea Week to Nov 30 77 reported each week over the last six months. -

LIBERIA War in Lofa County Does Not Justify Killing, Torture and Abduction

LIBERIA War in Lofa County does not justify killing, torture and abduction “One of the ATU [Anti-Terrorist Unit] told the others ‘He is going to give us information on the rebel business’. They took me to Gbatala. I saw many holes in which prisoners were held. I could hear them crying, calling for help and lamenting that they were hungry and they were dying.” Testimony of a young man detained at Gbatala military base in August 2000. Introduction The continuation of hostilities in Liberia cannot be used as a justification for killing, torture and abduction. Unarmed civilians are again the main victims of fighting in Liberia – a country still bearing the scars of its seven-year civil war when massive human rights abuses were committed by all sides with impunity. Since mid-2000, dozens of civilians have allegedly been extrajudicially executed and more than 100 civilians, including women, have been tortured by the Anti-Terrorist Unit (ATU) and other Liberian security forces. People have been tortured while held incommunicado, especially at the military base in Gbatala, central Liberia, and the ATU cells behind the Executive Mansion, the office of the presidency in Monrovia, the capital. Women and young girls have been raped by the security forces. All these victims were suspected of backing the armed incursions by Liberian armed opposition groups from Guinea into Lofa County, the northern region of Liberia bordering with Guinea and Sierra Leone. The security forces have mostly targeted members of the Mandingo ethnic group whom they associate with ULIMO-K 1 , a predominantly Mandingo warring faction in the 1989-1996 Liberian civil war, accused by the Liberian government of being responsible for the armed incursions into Lofa County in 1999, notably in April and August of that year and since July 2000. -

Newsletter ISSUE # 16 for Media Internews

http://www.usaid.gov/ https://www.internews.org/ http://www.healthcommcapacity.org/ Media Newsletter Information Saves Lives Issue #16 - June 27-July 3 http://on.fb.me/1NM9DKt/internewsliberia Welcome to the Internews Newsletter for media in Liberia. This newsletter is created with the intent to support the work of local media in reporting about Ebola and Ebola-related issues in Liberia. Internews welcomes feedback, comments and suggestions from all media receiving this newsletter and invites them to forward, share and re-post this newsletter as widely as possible. Three confirmed Ebola cases and 237 contacts in Margibi County This week one Ebola death and two additional live virus]. The Ministry of Health also does not rule out Ebola cases were confirmed in Liberia. Two individuals the possibility that the boy had sex with an Ebola were transported from Nedowein community to the survivor that transmitted the virus. Ebola Treatment Unit at ELWA. This makes the total of The Minister of Health, Bernice Dahn disclosed that three confirmed cases in Liberia. In total, 237 contacts when the boy began showing symptoms he visited a of the victims have been listed by the Ebola Task Force of Montserrado District four. According to Deputy clinic and got tested for malaria. He was tested positive Minister Nyenswah, there is no reason for panic as ‘the for malaria and was sent to his mother’s house in outbreak has been contained locally in the Nedowein Nedowein community. The boy appears to be moved community in Mama-Gaba district in Margibi County’. from his mother’s house to his father’s house in Smell th Five households are considered ‘high risk’ by the No Taste, where he died on the 28 . -

There Are Two Systems of Surveillance Operating in Burundi at Present

LIVELIHOOD ZONING ACTIVITY IN LIBERIA - UPDATE A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM NETWORK (FEWS NET) May 2017 1 LIVELIHOOD ZONING ACTIVITY IN LIBERIA - UPDATE A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM NETWORK (FEWS NET) April 2017 This publication was prepared by Stephen Browne and Amadou Diop for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), in collaboration with the Liberian Ministry of Agriculture, USAID Liberia, WFP, and FAO. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Page 2 of 60 Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................................... 5 Background and Introduction......................................................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 8 National Livelihood Zone Map .......................................................................................................12 National Seasonal Calendar ..........................................................................................................13 Timeline of Shocks and Hazards ....................................................................................................14 -

Republic of Liberia 2017 Annual Integrated Disease

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA 2017 ANNUAL INTEGRATED DISEASE SURVEILLANCE AND RESPONSE (IDSR) Preventing and Controlling BULLETIN Public Health Threats JANUARY – DECEMBER 2017 39 3 Disease Humanitarian Outbreaks Events Division of Infectious Disease and Epidemiology National Public Health Institute of Liberia Table of Contents EDITORIAL……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 I. OVERVIEW OF IDSR IN LIBERIA………………………………………………………………………………………………... 3 II. IDSR PERFORMANCE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 A. Reporting Coverage…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….3 B. Selected IDSR Performance Indicators…………………………………………………………………………………………6 C. National IDSR Supervision………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 D. IDSR Immediately Reportable Diseases/Events………………………………………………………………………………9 E. IDSR Monthly Reportable Diseases/Conditions………………………………………………………………………………10 III. OUTBREAKS AND HUMANITARIAN EVENTS………………………………………………………………………………… 11 A. Introduction……………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………11 B. Measles……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….12 C. Lassa fever…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..14 D. Human Monkeypox……………………………………………………………………………………………………….………..17 E. Meningococcal Disease…………………………………………………………………………………………………………...21 F. Floods/Mudslides…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...22 G. Chemical Spills………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………23 IV. DISEASES/CONDITIONS OF PUBLIC HEALTH IMPORTANCE…………………………………………………………….. 24 V. PUBLIC HEALTH DIAGNOSTICS……………………………………………………………………………………………….. -

Advancing Freedom of Information in Seven Liberian Counties

Freedom of Freedom of Information in Information in Action: Action: Advancing Freedom Advancing Freedom of Information in of Information in Seven Liberian Seven Liberian Counties Counties “...access to information is indispensable to genuine democracy and good governance and… no limitation shall be placed on the public right to be informed about the government and its functionaries.” Preamble, 2010 Liberian Freedom of Information Act This guide is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of The Carter Center and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. Photo Credits Pewee Flomoku: cover, pages 4,7,9 Deb Hakes: page 16 Catherine Schutz: page 12 Alphonsus Zeon: county coordinator photos on pages 7-9, 13-16 The Carter Center: pages 2, 9, 10, 11, 15 “...access to information is indispensable to genuine democracy and good governance and… no limitation shall be placed on the public right to be informed about the government and its functionaries.” Preamble, 2010 Liberian Freedom of Information Act Table of Contents Introduction 5 Grand Gedeh County: Poor Communities Benefit from County Development Funds 7 River Gee County: Freedom of Information Provides Avenues for Understanding 8 Bong County: FOI Compels Provision of Information on Development Projects 9 Meet George Toddy 10 New Bridges for the Community 11 Lofa County: Freedom of Information Enables Meaningful Participation and Action 13 Grand Bassa: Demand Leads to Automatic Publication of County Expenditures 14 Rural Montserrado County: FOI Request Accelerates Hospital Construction 15 Nimba County: FOI Request Exposes Illegal School Fee Collection 16 Introduction Liberia’s Freedom of Information Act, signed into law on September 16, 2010, provides all persons the right of access to public information. -

Report of the Panel of Experts on Liberia

United Nations S/2011/757 Security Council Distr.: General 7 December 2011 Original: English Letter dated 30 November 2011 from the Chairman of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1521 (2003) concerning Liberia addressed to the President of the Security Council On behalf of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1521 (2003) concerning Liberia, and in accordance with paragraph 6 (f) of Security Council resolution 1961 (2010), I have the honour to submit herewith the final report of the Panel of Experts on Liberia. I would appreciate it if the present letter, together with its enclosure, could be brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Nawaf Salam Chairman Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1521 (2003) concerning Liberia 11-60582 (E) 141211 *1160582* S/2011/757 Enclosure Letter dated 18 November 2011 from the Panel of Experts on Liberia addressed to the Chairman of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1521 (2003) concerning Liberia The members of the Panel of Experts on Liberia have the honour to transmit the final report of the Panel, prepared pursuant to paragraph 6 of Security Council resolution 1961 (2010). (Signed) Christian Dietrich (Coordinator) (Signed) Augusta Muchai (Signed) Caspar Fithen 2 11-60582 S/2011/757 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Liberia submitted pursuant to paragraph 6 (f) of Security Council resolution 1961 (2010) Summary Arms embargo The Panel of Experts identified one significant arms embargo violation committed by Liberian mercenaries and Ivorian combatants in River Gee County in May 2011. -

Empowering Youth, Opening up Perspectives - Employment Promotion As a Contribution to Peace Consolidation in South-East Liberia

SLE Publication Series – S… SLE Publication Series – S251 Seminar für Ländliche Entwicklung (SLE) – Centre for Rural Development Study commissioned by Welthungerhilfe in collaboration with the German Financial Cooperation-funded Reintegration and Recovery Program (RRP) and its partners IBIS and medica mondiale Liberia Empowering Youth, Opening up Perspectives - Employment Promotion as a Contribution to Peace Consolidation in South-East Liberia Dr. Ekkehard Kürschner (Teamleader), Joscha Albert, Emil Gevorgyan, Eva Jünemann, Elisabetta Mina, Jonathan Julius Ziebula Monrovia / Berlin, December 2012 Foreword i Foreword SLE Publication Series S251 For 50 years, the Centre for Rural Development (SLE - Seminar für Ländliche Entwicklung), Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, trains young professionals for the field of German and international development cooperation. Editor Humboldt Universität zu Berlin Three-month practical projects conducted on behalf of German and international Seminar für Ländliche Entwicklung (SLE) organisations in development cooperation form an integral part of the one-year Hessische Straße 1-2 postgraduate course. In interdisciplinary teams and under the guidance of an 10115 Berlin experienced team leader, young professionals carry out assignments on innovative Tel.: 0049-30-2093 6900 future-oriented topics, providing consultant support to the commissioning FAX: 0049-30-2093 6904 organisations. Involving a diverse range of actors in the process is of great [email protected] importance here, i.e. surveys from household level to decision makers and experts at www.sle-berlin.de national level. The outputs of this “applied research” directly contribute to solving specific development problems. Editorial Dr. Karin Fiege, SLE The studies are mostly linked to rural development (incl. management of natural resources, climate change, food security or agriculture), the cooperation with fragile or least developed countries (incl.