FGM in Liberia: Sande (2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberia BULLETIN Bimonthly Published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Liberia

LibeRIA BULLETIN Bimonthly published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - Liberia 1 October 2004 Vol. 1, Issue No. 4 Voluntary Repatriation Started October 1, 2004 The inaugural convoys of 77 Liberian refugees from Sierra Leone and 97 from Ghana arrived to Liberia on October 1, 2004, which marked the commencement of the UNHCR voluntary repatriation. Only two weeks prior to the beginning of the repatriation, the County Resettlement Assessment Committee (CRAC) pro- claimed four counties safe for return – Grand Cape Mount, Bomi, Gbarpolu and Margibi. The first group of refugees from Sierra Leone is returning to their homes in Grand Cape Mount. UNHCR is only facilitating re- turns to safe areas. Upon arrival, returnees have the option to spend a couple of nights in transit centers (TC) before returning to their areas of origin. At the TC, they received water, cooked meals, health care, as well as a two-months resettlement ration and a Non- Signing of Tripartite Agreement with Guinea Food Items (NFI) package. With the signing of the Tripartite Agreements, which took place in Accra, Ghana, on September 22, 2004 with the Ghanian government and in Monrovia, Liberia, on September 27, 2004 with the governments of Si- erra Leone, Guinea and Cote d’Ivorie, binding agree- ment has been established between UNHCR, asylum countries and Liberia. WFP and UNHCR held a regional meeting on Septem- ber 27, 2004 in Monrovia and discussed repatriation plans for Liberian refugees and IDPs. WFP explained that despite the current food pipeline constraints, the repatriation of refugees remains a priority for the Country Office. -

Baseline Survey | IRC/Lofa County CDD Program

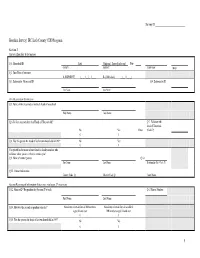

Survey ID _________________________ Baseline Survey | IRC/Lofa County CDD Program Section I Survey Identifier Information Q 1. Household ID: Lofa Voinjama | Zorzor [circle one] PA#: COUNTY DISTRICT TOWN NAME HH # Q 2. Date/Time of Interview: A. (DD/MM/YY) |__|__|/|__|__|/|__|__| B. (24 hr clock) |__|__| : |__|__| Q 3. Enumerator Name and ID: Q 4. Enumerator ID First Name Last Name First Respondent Information Q 5. Name of First respondent (normally head of household) First Name Last Name Q 6. Is first respondent the Head of Household? Q 7. Relation with head of Househod: No Yes If not: (Code P) 0 1 Q 8. Was this person the head of his/her own household in 1989? No Yes 0 1 Can you tell us the name of one friend or family member who will know where you are or how to contact you? Q 9. Name of contact person Q 10 First Name Last Name Relationship [Use Code P] Q 11. Contact Information County Code Q _____ _____ District Code Q ____ ____ ____ ____ Town Name ______________________________ Second Respondent Information (Enter once you begin 2nd interview) Q 12. Name of 2nd Respondent for (Section IV to end): Q 13 Roster Number: First Name Last Name Q 14. How was the second respondent selected? Randomly selected from all HH members Randomly selected from all available aged 18 and over HH members aged 18 and over 0 1 Q 15. Was this person the head of his own household in 1989? No Yes 0 1 1 Survey ID _________________________ II Pre War and Post War Household Roster I want you to think about your household today. -

Subproject Briefs

Liberia Energy Sector Support Program (LESSP) Subproject Briefs 8 July 2013 LESSP Subprojects Introduction • Seven Infrastructure Subprojects – OBJECTIVE 2 – Pilot RE Subprojects • Two hydro (one Micro [15 kW] and one Mini [1,000 kW]) • Two biomass power generation – OBJECTIVE 3 – Support to Liberia Energy Corporation (LEC) • 1000 kW Photovoltaic Power Station interconnected to LEC’s grid • 15 km Electric Distribution Line Extension to University of Liberia (UL) Fendell Campus – OBJECTIVE 3 - Grants – Public Private Partnership • One Biomass Power Generation Research and Demonstration (70 kW) • Total Cost: $ 13.97 Million USD (Engineer’s Estimate) • Service to: More than an estimated 72,000 Liberians (3,600 households and over 160 businesses and institutions) Subprojects Summary Data Project Cost, Service No LESSP Subprojects County kW Beneficiaries USD Population Million Mein River Mini Hydropower Subproject Bong 7.25 Over 3000 households, 150 1 1,000 Over 25,000 businesses and institutions Wayavah Falls Micro Hydropower Subproject Lofa 0.45 150 households and 4-5 2 15 Over 1,000 businesses/institutions Kwendin Biomass Electricity Subproject Nimba 0.487 248 households, a clinic, and a 3 60 Over 2,000 school Sorlumba Biomass Electricity Subproject Lofa 0.24 206 households, 8 institutions 4 35 Over 1,500 and businesses Grid connected 1 MW Solar PV Subproject Montserrado 3.95 5 1,000 LEC grid Over 15,000 MV Distribution Line Extension to Fendell Montserrado 1.12 6 Fendell Campus Over 25,000 Campus Establishment of the Liberia Center for Biomass Margibi 0.467 7 70 BWI Campus, RREA Over 2,200 Energy at BWI TOTAL - 5 counties 13.97 2,161 3,600 households and over 160 Over 72,000 businesses and institutions Liberia Energy Sector Support Program Subproject Brief: Mein River 1 MW Mini-Hydropower Subproject Location Suakoko District, Bong County (7o 8’ 11”N 9o 38’ 27” W) General Site The power house is 3 km uphill from the nearest road, outside the eco- Description tourism area of the Lower Kpatawee Falls. -

Ghana), 1922-1974

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN EWEDOME, BRITISH TRUST TERRITORY OF TOGOLAND (GHANA), 1922-1974 BY WILSON KWAME YAYOH THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY APRIL 2010 ProQuest Number: 11010523 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010523 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 DECLARATION I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for Students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. SIGNATURE OF CANDIDATE S O A S lTb r a r y ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of local government in the Ewedome region of present-day Ghana and explores the transition from the Native Authority system to a ‘modem’ system of local government within the context of colonization and decolonization. -

Transversal Politics and West African Security

Transversal Politics and West African Security By Moya Collett A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences and International Studies University of New South Wales, 2008 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed Moya Collett…………….............. Date 08/08/08……………………….............. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

Nimba's Profile

Nimba’s Profile The Flag of Nimba County: - (Valor, Purity and Fidelity reflected in the stripes) Nimba was part of the central province of Liberia which included Bong and Lofa. It became a full-fledged county in 1964 when President William V.S. Tubman changed the provinces into counties. Nimba became one of the original nine counties of Liberia. Over the years, other sub-divisions have been added making the total of 15 counties. Nimba is located in the North-East Region of the country. The size of Nimba is 4,650 square miles. In his book, Liberia Facing Mount Nimba, Dr. Nya Kwiawon Taryor, Sr. revealed that the name of the county "Nimba", originated from "Nenbaa ton" which means slippery mountain where beautiful young girls slip and fall. Mount Nimba is the highest mountain in Liberia. Nimba is the second largest county in Liberia in terms of population. Before the civil war in 1989, there were over 313,050 people in the county according to the 1984 census. Now Nimba Population has increased to 462,026. Nimba is also one of the richest in Liberia. It has the largest deposit of high grade iron ore. Other natural resources found in Nimba are gold, diamonds, timber, etc. In the late 50's, Nimba's huge iron ore reserve was exploited by LAMCO-the Liberian-American Swedish Mining Company. A considerable portion of Liberia's Gross Domestic Product, GDP, was said to have been generated from revenues from Nimba's iron ore for several years. The Flag of Nimba County: - (Valor, Purity and Fidelity reflected in the stripes) There are negotiations going on for a new contract for the iron ore in Nimba. -

Smallholder Household Labour Characteristics, Its Availability And

V SMAIJJIOLDER HOUSEHOLD LABOUR CHARACTERISTICS, ITS AVAILABILITY AND UTILIZATION IN THREE SETTLEMENTS OF LAIKIPIA DISTRICT, ____ a KENYA. rN AcCl'AvtBD lf0U BY IBS'S r 'S BtE - . a ..... JOHN IE CHRISOSTOM jo PONDO A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Master of Arts (Anthropology) at, the Institute of African studies, University of Nairobi. t+\*4 DECLARATION This is my original work and has not been presented at any other University for the award of a degree. signed ....................... Johnie Chrisostom opondo Date: This work has been presented with my approval as University Supervisor. Date: 13' oh DEDICATION To my parents Cosmas and Sylvia Opondo for their love, incessant support and encouragement in my studies. TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Acknowledgement................................................v Abstract...................................................... vi CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. Background................................................. 1 1.2. Laikipia in retrospect................................... 3 1.3 .Statement of the problem.................................. 5 1.4. The objectives of the study..............................9 1.5. The scope and limitations of the study.................. 9 1.6. The significance of the study.......................... 10 1.7. The synopsis............................................ 12 CHAPTER TWO : LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL ORIENTATION 13 2.0. Introduction.............................................33 2.1. Division of labour in -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

S/2009/299 Security Council

United Nations S/2009/299 Security Council Distr.: General 10 June 2009 Original: English Special report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Liberia I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 1836 (2008), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) until 30 September 2009, and requested me to report on progress made towards achieving the core benchmarks set out in my reports of 8 August 2007 (S/2007/479) and 19 March 2008 (S/2008/183) and, based on that progress, make recommendations on any further adjustments to the military and police components of UNMIL. My report of 10 February 2009 (S/2009/86) provided preliminary recommendations regarding the third stage of the Mission’s drawdown and indicated that precise proposals would be submitted to the Council based on the findings of a technical assessment mission. The present report outlines the findings of that assessment mission and my recommendations for the third stage of the UNMIL drawdown. II. Technical assessment mission 2. The technical assessment mission, which was led by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations and comprised participants from the Department of Field Support, the Department of Political Affairs, the Department of Safety and Security and, in situ, UNMIL and the United Nations country team, visited Liberia from 26 April to 6 May. The mission received detailed briefings from UNMIL and the United Nations country team and consulted a broad cross-section of Liberian and international stakeholders, including -

Where Have All the (Qualified) Teachers Gone?

African Educational Research Journal Vol. 6(2), pp. 30-47, April 2018 DOI: 10.30918/AERJ.62.18.013 ISSN: 2354-2160 Full Length Research Paper Where have all the (qualified) teachers gone? Implications for measuring sustainable development goal target 4.c from a study of teacher supply, demand and deployment in Liberia Mark Ginsburg*, Noor Ansari, Oscar N. Goyee, Rachel Hatch, Emmanuel Morris and Delwlebo Tuowal 1University of Maryland, USA. 2Universidad de Ciencias Pedagógicas Enrique José Varona, Cuba. Accepted 3 April, 2018 ABSTRACT This paper analyzes data collected in the 2013 Liberian Annual School Census undertaken as part of the Educational Management Information System and supplemented by information gathered from teacher education program organizers as well as from samples of graduates from preservice and inservice C- Certificate granting programs undertaken in Liberia in during 2007 to 2013. The authors report that the percentage of “qualified” primary school teachers (that is, those with at least a C-Certificate, which Liberian policy sets as the minimum qualification) expanded dramatically after the education system was decimated during the years of civil war (1989 to 2003). We also indicate that in government primary schools in 2013, the pupil-teacher ratio (24.8) and even the pupil-qualified teacher ratio (36.2) was lower – that is, better – than the policy goal of 44 pupils per teacher. However, teacher hiring and deployment decisions led to large inequalities in these input measures of educational quality. At the same time, the authors discovered that the findings from the analysis of Liberia’s 2013 EMIS data did not fully answer the question of where the (qualified) teachers are, in that we were not able to locate in the EMIS database substantial numbers of graduates of the various C-Certificate teacher education programs. -

Liberia Electricity Corporation (Lec) and Rural and Rrenewable Energy Agency (Rrea)

Public Disclosure Authorized LIBERIA ELECTRICITY CORPORATION (LEC) AND RURAL AND RRENEWABLE ENERGY AGENCY (RREA) Public Disclosure Authorized Liberia Electricity Sector Strengthening and Access Project (LESSAP) Resettlement Policy Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Draft Report November 2020 SQAT: January 12, 2021 Public Disclosure Authorized Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................ 1 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 2 1.1 Project Description ......................................................................................... 3 1.2 Objective and Rationale of the Resettlement Policy Framework .................. 7 1.3 Project Locations, Beneficiaries and Project Affected People ...................... 8 1.4 Institutional Capacity ................................................................................... 10 1.5 Baseline Information Required for Projects ................................................. 10 1.5.1 Overview ........................................................................................................ 10 1.5.2 Montserrado County ...................................................................................... 12 1.5.3 Grand Bassa County ...................................................................................... 12 1.5.4 Margibi County .............................................................................................. 13 1.5.5 -

2008 National Population and Housing Census: Preliminary Results

GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA 2008 NATIONAL POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS: PRELIMINARY RESULTS LIBERIA INSTITUTE OF STATISTICS AND GEO-INFORMATION SERVICES (LISGIS) MONROVIA, LIBERIA JUNE 2008 FOREWORD Post-war socio-economic planning and development of our nation is a pressing concern to my Government and its development partners. Such an onerous undertaking cannot be actualised with scanty, outdated and deficient databases. Realising this limitation, and in accordance with Article 39 of the 1986 Constitution of the Republic of Liberia, I approved, on May 31, 2007, “An Act Authorizing the Executive Branch of Government to Conduct the National Census of the Republic of Liberia”. The country currently finds itself at the crossroads of a major rehabilitation and reconstruction. Virtually every aspect of life has become an emergency and in resource allocation, crucial decisions have to be taken in a carefully planned and sequenced manner. The publication of the Preliminary Results of the 2008 National Population and Housing Census and its associated National Sampling Frame (NSF) are a key milestone in our quest towards rebuilding this country. Development planning, using the Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS), decentralisation and other government initiatives, will now proceed into charted waters and Government’s scarce resources can be better targeted and utilized to produce expected dividends in priority sectors based on informed judgment. We note that the statistics are not final and that the Final Report of the 2008 Population and Housing Census will require quite sometime to be compiled. In the interim, I recommend that these provisional statistics be used in all development planning for and in the Republic of Liberia.