Where's the Fair Use? Participatory Culture, Creativity, and Copyright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youtube Comments As Media Heritage

YouTube comments as media heritage Acquisition, preservation and use cases for YouTube comments as media heritage records at The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision Archival studies (UvA) internship report by Jack O’Carroll YOUTUBE COMMENTS AS MEDIA HERITAGE Contents Introduction 4 Overview 4 Research question 4 Methods 4 Approach 5 Scope 5 Significance of this project 6 Chapter 1: Background 7 The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision 7 Web video collection at Sound and Vision 8 YouTube 9 YouTube comments 9 Comments as archival records 10 Chapter 2: Comments as audience reception 12 Audience reception theory 12 Literature review: Audience reception and social media 13 Conclusion 15 Chapter 3: Acquisition of comments via the YouTube API 16 YouTube’s Data API 16 Acquisition of comments via the YouTube API 17 YouTube API quotas 17 Calculating quota for full web video collection 18 Updating comments collection 19 Distributed archiving with YouTube API case study 19 Collecting 1.4 billion YouTube annotations 19 Conclusions 20 Chapter 4: YouTube comments within FRBR-style Sound and Vision information model 21 FRBR at Sound and Vision 21 YouTube comments 25 YouTube comments as derivative and aggregate works 25 Alternative approaches 26 Option 1: Collect comments and treat them as analogue for the time being 26 Option 2: CLARIAH Media Suite 27 Option 3: Host using an open third party 28 Chapter 5: Discussion 29 Conclusions summary 29 Discussion: Issue of use cases 29 Possible use cases 30 Audience reception use case 30 2 YOUTUBE -

Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21St Century

An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. Robison Margaret Weigel Building the new field of digital media and learning The MacArthur Foundation launched its five-year, $50 million digital media and learning initiative in 2006 to help determine how digital technologies are changing the way young people learn, play, socialize, and participate in civic life.Answers are critical to developing educational and other social institutions that can meet the needs of this and future generations. The initiative is both marshaling what it is already known about the field and seeding innovation for continued growth. For more information, visit www.digitallearning.macfound.org.To engage in conversations about these projects and the field of digital learning, visit the Spotlight blog at spotlight.macfound.org. About the MacArthur Foundation The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private, independent grantmaking institution dedicated to helping groups and individuals foster lasting improvement in the human condition.With assets of $5.5 billion, the Foundation makes grants totaling approximately $200 million annually. For more information or to sign up for MacArthur’s monthly electronic newsletter, visit www.macfound.org. The MacArthur Foundation 140 South Dearborn Street, Suite 1200 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Tel.(312) 726-8000 www.digitallearning.macfound.org An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. -

Make a Mini Dance

OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Parent Guide Read the “Directions” sheets for step-by-step instructions. SUMMARY In this activity children will watch two very short videos online, then create their own mini dances. WHY This activity will get children thinking about the ways their bodies move. They will think about how movements can represent shapes, such as letters in a word. TIME ■ 10–20 minutes RECOMMENDED AGE GROUP This activity will work best for children in kindergarten through 4th grade. GET READY ■ Read Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring together. Ballet for Martha tells the story of three artists who worked together to make a treasured work of American art. For tips on reading this book together, check out the Guided Reading Activity (http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/pdf/dance/dance_reading.pdf). ■ Read the Step Back in Time sheets. YOU NEED ■ Directions sheets (attached) ■ Ballet for Martha book (optional) ■ Step Back in Time sheets (attached) ■ ThinkAbout sheet (attached) ■ Open space to move ■ Video camera (optional) ■ Computer with Internet and speakers/headphones More information at http://americanhistory.si.edu/ourstory/activities/dance/. OurStory: An American Story in Dance and Music Make a Mini Dance Directions, page 1 of 2 For adults and kids to follow together. 1. On May 11, 2011, the Internet search company Google celebrated Martha Graham’s birthday with a special “Google Doodle,” which spelled out G-o-o-g-l-e using a dancer’s movements. Take a look at the video (http://www.google.com/logos/2011/ graham.html). -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Youtube Yrityksen Markkinoinnin Välineenä

Lassi Tuomikoski Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu Tradenomi Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Lokakuu 2014 Tiivistelmä Tekijä Lassi Tuomikoski Otsikko Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Sivumäärä 47 sivua + 2 liitettä Aika 9.11.2014 Tutkinto Tradenomi Koulutusohjelma Liiketalous Suuntautumisvaihtoehto Markkinointi Ohjaaja lehtori Raisa Varsta Tämän opinnäytetyön tarkoituksena oli luoda ohjeistus oman sisällön luomiseen Youtubessa aloittelevalle yritykselle. Työn toisena tavoitteena on osoittaa, miten yritys pystyy hyödyntämään videonjakopalvelu Youtubea omassa liiketoiminnassaan muiden markkinoinnin keinojen avulla. Työn viitekehyksessä käydään läpi keskeisimmät käsitteet ja termit ja esitellään Youtube yrityksenä sekä videonjakopalveluna. Työssä kerrotaan, millä eri tavoin yritys voi näkyä Youtubessa ja Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnissa. Toiminnallisena osana työtä tuotettiin konkreettisten esimerkkien pohjalta ohjeistus Youtuben parissa aloittelevalle yritykselle siitä, kuinka päästä alkuun tehokkaassa ja yritykselle lisäarvoa tuottavassa sisällöntuottamisessa. Mitä asiota oman sisällön luomisessa täytyy ottaa huomioon ja millä keinoilla Youtubessa voidaan menestyä. Opinnäytetyön johtopäätöksenä todettiin, että ennen oman sisällön luomista on yrityksen sisältöstrategian oltava kunnossa. Sisällön tärkeyttä ei voi oman sisällön luomisessa tarpeeksi korostaa. Sisällön on oltava merkityksellistä asiakkaan kannalta. Avainsanat youtube, sisältömarkkinointi, sosiaalinen media Abstract -

The State of the Art and Evolution of Cable Television and Broadband Technology

The State of the Art and Evolution of Cable Television and Broadband Technology Prepared for the City of Seattle, Washington October 9, 2013 Cable and Broadband State-of-the-Art TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Evolution of Underlying Infrastructure ................................................................................... 3 2.1 Infrastructure Upgrades .......................................................................................................... 3 2.1.1 Cable Migration Path ....................................................................................................... 4 2.1.1.1 Upgrade from DOCSIS 3.0 to DOCSIS 3.1 ................................................................... 4 2.1.1.2 Ethernet PON over Coax (EPoC) Architecture ............................................................ 8 2.2 Internet Protocol (IP) Migration and Convergence ............................................................... 10 2.2.1 Converged Cable Access Platform (CCAP) ..................................................................... 10 2.2.2 Migration from IPv4 to IPv6 Protocol ............................................................................ 13 2.2.3 IP Transport of Video on Demand (VoD) ....................................................................... 14 2.2.4 Multicasting—IP Transport of Video Channels .............................................................. 15 2.3 -

2045 the Year Man Becomes Immortal by LEV GROSSMAN Thursday, Feb

2045 The Year Man Becomes Immortal By LEV GROSSMAN Thursday, Feb. 10, 2011 Photo--Illustration by Phillip Toledano for TIME On Feb. 15, 1965, a diffident but self-possessed high school student named Raymond Kurzweil appeared as a guest on a game show called I've Got a Secret. He was introduced by the host, Steve Allen, then he played a short musical composition on a piano. The idea was that Kurzweil was hiding an unusual fact and the panelists — they included a comedian and a former Miss America — had to guess what it was. On the show (see the clip on YouTube), the beauty queen did a good job of grilling Kurzweil, but the comedian got the win: the music was composed by a computer. Kurzweil got $200. (See TIME's photo-essay "Cyberdyne's Real Robot.") Kurzweil then demonstrated the computer, which he built himself — a desk-size affair with loudly clacking relays, hooked up to a typewriter. The panelists were pretty blasé about it; they were more impressed by Kurzweil's age than by anything he'd actually done. They were ready to move on to Mrs. Chester Loney of Rough and Ready, Calif., whose secret was that she'd been President Lyndon Johnson's first-grade teacher. But Kurzweil would spend much of the rest of his career working out what his demonstration meant. Creating a work of art is one of those activities we reserve for humans and humans only. It's an act of self-expression; you're not supposed to be able to do it if you don't have a self. -

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com -

In What Way Is the Rhetoric Used in Youtube Videos Altering the Perception of the LGBTQ+ Community for Both Its Members and Non-Members?

In What Way Is the Rhetoric Used in YouTube Videos Altering the Perception of the LGBTQ+ Community for Both Its Members and Non-Members? NATALIE MAURER Produced in Thomas Wright’s Spring 2018 ENC 1102 Introduction The LBGTQ community has become a much more prevalent part of today's society. Over the past several years, the LGBTQ community has been recognized more equally in comparison to other groups in society. June 2015 was a huge turning point for the community due to the legalization of same sex marriage. The legalization of same sex marriage in June 2015 had a great impact on the LBGTQ community, as well as non-members. With an increase in new media platforms like YouTube, content on the LGBTQ community has become more accessible and more prevalent than decades ago. LGBTQ media has been represented in movies, television shows, short videos, and even books. The exposure of LQBTQ characters in a popular 2000s sitcom called Will & Grace paved the way for LGBTQ representation in media. A study conducted by Edward Schiappa and others concluded that exposure to LGBTQ communities through TV helped educate Americans, therefore reducing sexual prejudice. Unfortunately, the way the LBGTQ community is portrayed through online media such as YouTube has an effect on LGBTQ members and non-members, and it has yet to be studied. Most “young people's experiences are affected by the present context characterized by the rapidly increasing prevalence of new (online) media” because of their exposure to several media outlets (McInroy and Craig 32). This gap has led to the research question does the LGBTQ representation on YouTube negatively or positively represent this community to its members, and in what way is the community impacted by this representation as well as non- members? One positive way the LGBTQ community was represented through media was on the popular TV show Will & Grace. -

Systematic Scoping Review on Social Media Monitoring Methods and Interventions Relating to Vaccine Hesitancy

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy www.ecdc.europa.eu ECDC TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy This report was commissioned by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and coordinated by Kate Olsson with the support of Judit Takács. The scoping review was performed by researchers from the Vaccine Confidence Project, at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (contract number ECD8894). Authors: Emilie Karafillakis, Clarissa Simas, Sam Martin, Sara Dada, Heidi Larson. Acknowledgements ECDC would like to acknowledge contributions to the project from the expert reviewers: Dan Arthus, University College London; Maged N Kamel Boulos, University of the Highlands and Islands, Sandra Alexiu, GP Association Bucharest and Franklin Apfel and Sabrina Cecconi, World Health Communication Associates. ECDC would also like to acknowledge ECDC colleagues who reviewed and contributed to the document: John Kinsman, Andrea Würz and Marybelle Stryk. Suggested citation: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020. Stockholm, February 2020 ISBN 978-92-9498-452-4 doi: 10.2900/260624 Catalogue number TQ-04-20-076-EN-N © European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

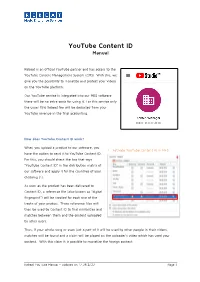

Manual Youtube Content ID

YouTube Content ID Manual Rebeat is an official YouTube partner and has access to the YouTube Content Management System (CMS). With this, we give you the possibility to monetize and protect your videos on the YouTube platform. Our YouTube service is integrated into our MES software – there will be no extra costs for using it. For this service only the usual 15% Rebeat fee will be deducted from your YouTube revenue in the final accounting. How does YouTube Content ID work? When you upload a product to our software, you 1. Activate YouTube Content ID in MES have the option to send it to YouTube Content ID. For this, you should check the box that says “YouTube Content ID” in the distribution matrix of our software and apply it for the countries of your choosing (1). As soon as the product has been delivered to Content ID, a reference file (also known as “digital fingerprint”) will be created for each one of the tracks of your product. These reference files will then be used by Content ID to find similarities and matches between them and the content uploaded by other users. Thus, if your whole song or even just a part of it will be used by other people in their videos, matches will be found and a claim will be placed on the uploader’s video which has used your content. With this claim it is possible to monetize the foreign content. Rebeat YouTube Manual – updated on 17.08.2020 Page 1 With the help of Content ID we can also claim any of your content manually.