You(Tube), Me, and Content ID: Paving the Way for Compulsory Synchronization Licensing on User-Generated Content Platforms Nicholas Thomas Delisa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFLUENCE Music Marketing Meets Social Influencers COVERFEATURE

06-07 Tools Kombie 08-09 Campaigns YACHT, Radiohead, James Blake 10-14 Behind The Campaign Aurora MAY 18 2016 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 157 UNDER THE INFLUENCE music marketing meets social influencers COVERFEATURE In the old days, there were a handful of gatekeepers – press, TV and radio – and getting music in front of them was hard, UNDER THE INFLUENCE but not impossible. Today, traditional media still holds significant power, but the number of influencers out there has shot up exponentially with the explosion of social media in general and YouTube in particular. While the world’s largest video service might be under fire over its (low) royalty rates, the music industry is well aware that its biggest stars offer a direct route to the exact audiences they want their music to reach. We look at who these influencers are, how they can be worked with and the things that will make them back or blank you. etting your act heard used to be, if not exactly easy, then at least relatively Gstraightforward for the music business: you’d schmooze the radio playlist heads, take journalists out to a gig and pray for some TV coverage, all while splashing out on magazine and billboard advertising. The digital era – and especially social media – have shaken this all up. Yes, traditional media is still important; but to this you can add a sometimes bewildering list of “social influencers”, famous faces on platforms like YouTube, Snapchat and Instagram, plus vloggers, Viners and the music marketing meets rest, all of whom (for now) wield an uncanny power over youthful audiences. -

Circular 1 Copyright Basics

CIRCULAR 1 Copyright Basics Copyright is a form of protection Copyright is a form of protection provided by the laws of the provided by U.S. law to authors of United States to the authors of “original works of authorship” that are fixed in a tangible form of expression. An original “original works of authorship” from work of authorship is a work that is independently created by the time the works are created in a a human author and possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity. A work is “fixed” when it is captured (either fixed form. This circular provides an by or under the authority of an author) in a sufficiently overview of basic facts about copyright permanent medium such that the work can be perceived, and copyright registration with the reproduced, or communicated for more than a short time. Copyright protection in the United States exists automatically U.S. Copyright Office. It covers from the moment the original work of authorship is fixed.1 • Works eligible for protection • Rights of copyright owners What Works Are Protected? • Who can claim copyright • Duration of copyright Examples of copyrightable works include • Literary works • Musical works, including any accompanying words • Dramatic works, including any accompanying music • Pantomimes and choreographic works • Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works • Motion pictures and other audiovisual works • Sound recordings, which are works that result from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds • Architectural works These categories should be viewed broadly for the purpose of registering your work. For example, computer programs and certain “compilations” can be registered as “literary works”; maps and technical drawings can be registered as “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works.” w copyright.gov note: Before 1978, federal copyright was generally secured by publishing a work with an appro- priate copyright notice. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

The Constitutional Law of Intellectual Property After Eldred V. Ashcroft

The Constitutional Law of Intellectual Property After Eldred v. Ashcroft By Pamela Samuelson* I. Introduction The past decade has witnessed an extraordinary blossoming of scholarship on the constitutional law of intellectual property,1 much of which focuses on copyright law.2 Had the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Eldred’s challenge to the constitutionality of the Copyright Term Extension Act,3 this body of scholarship would have undoubtedly proliferated with alacrity. Many scholars would have been eager to offer interpretations of implications of an Eldred-favorable decision for other intellectual property disputes.4 Given the Ashcroft-favorable outcome, some may expect the Eldred decision to “deconstitutionalize” intellectual property law and reduce to a trickle further scholarly * Chancellor’s Professor of Law and Information Management, University of California at Berkeley. Research support for this article was provided by NSF Grant No. SES 9979852. I wish to thank Eddan Katz for his exceptional research assistance with this article. 1 See, e.g., Dan L. Burk, Patenting Speech, 79 Tex. L. Rev. 99 (2000); Paul J. Heald and Suzanna Sherry, Implied Limits on the Legislative Power: The Intellectual Property Clause as an Absolute Constraint on Congress, 2000 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1119 (2000); Robert Patrick Merges and Glenn Harlan Reynolds, The Proper Scope of the Copyright and Patent Power, 37 J. Legis. 45 (2000); Mark A. Lemley, The Constitutionalization of Technology Law, 15 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 529 (2000); Malla Pollack, Unconstitutional Incontestability? The Intersection Of The Intellectual Property And Commerce Clauses Of The Constitution: Beyond A Critique Of Shakespeare Co. v. -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Free Views Tiktok

Free Views Tiktok Free Views Tiktok CLICK HERE TO ACCESS TIKTOK GENERATOR tiktok auto liker hack In July 2021, "The Wall Street Journal" reported the company's annual revenue to be approximately $800 million with a loss of $70 million. By May 2021, it was reported that the video-sharing app generated $5.2 billion in revenue with more than 500 million users worldwide.", free vending machine code tiktok free pro tiktok likes and followers free tiktok fans without downloading any apps The primary difference between Tencent’s WeChat and ByteDance’s Toutiao is that the former has yet to capitalize on the addictive nature of short-form videos, whereas the latter has. TikTok — the latter’s new acquisition — is a comparatively more simple app than its parent company, but it does fit in well with Tencent’s previous acquisition of Meitu, which is perhaps better known for its beauty apps.", In an article published by The New York Times, it was claimed that "An app with more than 500 million users can’t seem to catch a break. From pornography to privacy concerns, there have been quite few controversies surrounding TikTok." It continued by saying that "A recent class-action lawsuit alleged that the app poses health and privacy risks to users because of its allegedly discriminatory algorithm, which restricts some content and promotes other content." This article was published on The New York Times.", The app has received criticism from users for not creating revenue and posting ads on videos which some see as annoying. The app has also been criticized for allowing children younger than age 13 to create videos. -

Youtube Yrityksen Markkinoinnin Välineenä

Lassi Tuomikoski Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulu Tradenomi Liiketalouden koulutusohjelma Opinnäytetyö Lokakuu 2014 Tiivistelmä Tekijä Lassi Tuomikoski Otsikko Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnin välineenä Sivumäärä 47 sivua + 2 liitettä Aika 9.11.2014 Tutkinto Tradenomi Koulutusohjelma Liiketalous Suuntautumisvaihtoehto Markkinointi Ohjaaja lehtori Raisa Varsta Tämän opinnäytetyön tarkoituksena oli luoda ohjeistus oman sisällön luomiseen Youtubessa aloittelevalle yritykselle. Työn toisena tavoitteena on osoittaa, miten yritys pystyy hyödyntämään videonjakopalvelu Youtubea omassa liiketoiminnassaan muiden markkinoinnin keinojen avulla. Työn viitekehyksessä käydään läpi keskeisimmät käsitteet ja termit ja esitellään Youtube yrityksenä sekä videonjakopalveluna. Työssä kerrotaan, millä eri tavoin yritys voi näkyä Youtubessa ja Youtube yrityksen markkinoinnissa. Toiminnallisena osana työtä tuotettiin konkreettisten esimerkkien pohjalta ohjeistus Youtuben parissa aloittelevalle yritykselle siitä, kuinka päästä alkuun tehokkaassa ja yritykselle lisäarvoa tuottavassa sisällöntuottamisessa. Mitä asiota oman sisällön luomisessa täytyy ottaa huomioon ja millä keinoilla Youtubessa voidaan menestyä. Opinnäytetyön johtopäätöksenä todettiin, että ennen oman sisällön luomista on yrityksen sisältöstrategian oltava kunnossa. Sisällön tärkeyttä ei voi oman sisällön luomisessa tarpeeksi korostaa. Sisällön on oltava merkityksellistä asiakkaan kannalta. Avainsanat youtube, sisältömarkkinointi, sosiaalinen media Abstract -

Youtube Decade: Cultural Convergence in Recorded Music∗

YouTube Decade: Cultural Convergence in Recorded Music∗ Lisa M. George Christian Peukert Hunter College and University of Zurich the Graduate Center, CUNY June 17, 2016 Abstract Digital technology has the potential to impact the diffusion of new goods both within and across markets. The net effect of technology on globalization is thus an empirical question. We study the role of YouTube in globalizing the market for recorded music. We consider the US, Germany and Austria, exploiting a natural experiment that has blocked official music videos on YouTube in Germany since 2009. We document a causal link between YouTube access and both global and local outcomes. YouTube increases overlap with US weekly top charts, a globalizing effect, but also induces greater chart penetration of domestic music, a local effect. We show that the dual result is driven in part by the dynamics of the market: YouTube increases chart turnover, which expands the market for domestic titles. Our results indicate that global platforms need not advantage global culture. Keywords: Digitization, Trade, Globalization, Media, Superstars, Natural Experiment JEL No.: L82, O33, D83 ∗The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of this research by the NET Institute, http://www.NETinst.org. Lisa M. George, Department of Economics, Hunter College, 695 Park Ave., New York, NY 10065. Email: [email protected]. Christian Peukert, Chair for Entrepreneurship, University of Zurich, Affolternstrasse 56, 8050 Z¨urich, Switzerland. Email: [email protected]. 1 Introduction Twentieth century innovations in media technology influenced the adoption and diffusion of new goods, and in some cases the industrial organization of product markets themselves. -

Cyber Piracy: Can File Sharing Be Regulated Without Impeding the Digital Revolution?

CYBER PIRACY: CAN FILE SHARING BE REGULATED WITHOUT IMPEDING THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION? Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester Michael Robert Filby School of Law University of Leicester May 2012 Cyber Piracy: Can File Sharing be Regulated without Impeding the Digital Revolution? Abstract This thesis explores regulatory mechanisms of managing the phenomenon of file sharing in the online environment without impeding key aspects of digital innovation, utilising a modified version of Lessig’s modalities of regulation to demonstrate significant asymmetries in various regulatory approaches. After laying the foundational legal context, the boundaries of future reform are identified as being limited by extra-jurisdictional considerations, and the regulatory direction of legal strategies to which these are related are linked with reliance on design-based regulation. The analysis of the plasticity of this regulatory form reveals fundamental vulnerabilities to the synthesis of hierarchical and architectural constraint, that illustrate the challenges faced by the regulator to date by countervailing forces. Examination of market-based influences suggests that the theoretical justification for the legal regulatory approach is not consistent with academic or policy research analysis, but the extant effect could impede openness and generational waves of innovation. A two-pronged investigation of entertainment industry-based market models indicates that the impact of file sharing could be mitigated through adaptation of the traditional model, or that informational decommodification could be harnessed through a suggested alternative model that embraces the flow of free copies. The latter model demonstrates how the interrelationships between extant network effects and sub-model externalities can be stimulated to maximise capture of revenue without recourse to disruption. -

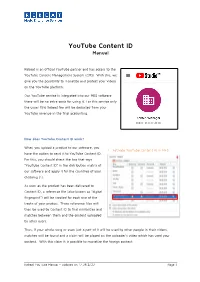

Manual Youtube Content ID

YouTube Content ID Manual Rebeat is an official YouTube partner and has access to the YouTube Content Management System (CMS). With this, we give you the possibility to monetize and protect your videos on the YouTube platform. Our YouTube service is integrated into our MES software – there will be no extra costs for using it. For this service only the usual 15% Rebeat fee will be deducted from your YouTube revenue in the final accounting. How does YouTube Content ID work? When you upload a product to our software, you 1. Activate YouTube Content ID in MES have the option to send it to YouTube Content ID. For this, you should check the box that says “YouTube Content ID” in the distribution matrix of our software and apply it for the countries of your choosing (1). As soon as the product has been delivered to Content ID, a reference file (also known as “digital fingerprint”) will be created for each one of the tracks of your product. These reference files will then be used by Content ID to find similarities and matches between them and the content uploaded by other users. Thus, if your whole song or even just a part of it will be used by other people in their videos, matches will be found and a claim will be placed on the uploader’s video which has used your content. With this claim it is possible to monetize the foreign content. Rebeat YouTube Manual – updated on 17.08.2020 Page 1 With the help of Content ID we can also claim any of your content manually. -

Here Are So Many People, Decisions and Steps in Between That Are Rarely Discussed

** SCHEDULE OF SPECIAL EVENTS AND INDUSTRY PANELS BELOW BY DATE** (***Additions to Be Announced asap***) THURSDAY, JUNE 24 EPSTEIN’S SHADOW: GHISLAINE MAXWELL (Peacock; June 24)-OPENING NIGHT EVENT In Attendance: Barbara Shearer (Director & Executive Producer), Jennifer Harkness, Nina Burleigh and Emma Cooper (Executive Producers) The documentary series will investigate the powerful, connected, and mysterious Ghislaine Maxwell, who was once the heiress to the Maxwell fortune but whose life takes a sordid downturn when she meets Jeffrey Epstein, the serial sex offender. This investigative series will reveal a complicated story of power, sex, and money, which leads to Ghislaine Maxwell’s arrest awaiting trial in November 2021. The series, titled “Ghislaine Maxwell: Epstein’s Shadow,” will also premiere on Sky Documentaries and streaming service NOW in the UK on June 28. Deadline INSIDE LOOK: THE DAILY SHOW WITH TREVOR NOAH (Comedy Central; Weeknights)- PANEL In Attendance: Desi Lydic and Dulcé Sloan (Correspondents), Jen Flanz (Executive Producer and Showrunner), Zhubin Parang (Supervising Producer and Writer), and Dan Amira (Head Writer and Producer) Between a global pandemic and countless social justice crises this past year, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah offered both levity and crucial commentary on some of today’s most uncomfortable truths. Sit down with The Daily Show’s creative team to discuss how the show works behind the scenes to tackle tough conversations, elevate underrepresented voices and navigate the unforeseen challenges of 2020—all while making the audience laugh. Veteran creatives and correspondents share their insight on what it takes to make a successful show and keep audiences engaged 24/7 with not just the program, but also more broadly with the world around them. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. •>- I The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrougb, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.