INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Adventures of the Amazing Revelators

The Adventures of the Amazing Revelators "I don't see this as a greatest hits recording, more an opportunity to pay homage to some of the great writers of our time. The Revelators were formed out of a desire to keep this music alive. Some of these songs have been with us for some time - others we were drawn to because of their charm.... and every word is true." Joe Camilleri These were the words that graced The Revelators' 1991 debut CD release. 'Debut' is an odd word to use for a group of musicians who have been an integral part of the Australian music scene for so long. The Revelators The Revelators story started in the late 80's when Joe Camilleri, along with friends James Black and Joe Creighton, took to the stage as 'The Delta Revelators' . Their desire was to blow out the serious days' work with people who shared the same interest in music and who simply wanted to play it. On stage with Pete Luscombe on drums (Black Sorrows, Paul Kelly, Rebecca's Empire) and Jeff Burstin on guitar (Black Sorrows, Vika & Linda) the word spread that this was a great band. Soon the occasional gig was not enough to keep the punters happy. Regular sessions at ID's (now The Continental) and The Botanical Hotel had the fans asking 'When are you going to do a CD?' 'Amazing Stories' 'Amazing Stories' was released in 1991 and everyone in the band agreed it was the best album they had ever made. The fans felt the same and the CD is still eagerly sought after by roots music aficionados. -

Jerry Williams Jr. Discography

SWAMP DOGG - JERRY WILLIAMS, JR. DISCOGRAPHY Updated 2016.January.5 Compiled, researched and annotated by David E. Chance: [email protected] Special thanks to: Swamp Dogg, Ray Ellis, Tom DeJong, Steve Bardsley, Pete Morgan, Stuart Heap, Harry Grundy, Clive Richardson, Andy Schwartz, my loving wife Asma and my little boy Jonah. News, Info, Interviews & Articles Audio & Video Discography Singles & EPs Albums (CDs & LPs) Various Artists Compilations Production & Arrangement Covers & Samples Miscellaneous Movies & Television Song Credits Lyrics ================================= NEWS, INFO, INTERVIEWS & ARTICLES: ================================= The Swamp Dogg Times: http://www.swampdogg.net/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/SwampDogg Twitter: https://twitter.com/TheSwampDogg Swamp Dogg's Record Store: http://swampdogg.bandcamp.com/ http://store.fastcommerce.com/render.cz?method=index&store=sdeg&refresh=true LIVING BLUES INTERVIEW The April 2014 issue of Living Blues (issue #230, vol. 45 #2) has a lengthy interview and front cover article on Swamp Dogg by Gene Tomko. "There's a Lot of Freedom in My Albums", front cover + pages 10-19. The article includes a few never-before-seen vintage photos, including Jerry at age 2 and a picture of him talking with Bobby "Blue" Bland. The issue can be purchased from the Living Blues website, which also includes a nod to this online discography you're now viewing: http://www.livingblues.com/ SWAMP DOGG WRITES A BOOK PROLOGUE Swamp Dogg has written the prologue to a new book, Espiritus en la Oscuridad: Viaje a la era soul, written by Andreu Cunill Clares and soon to be published in Spain by 66 rpm Edicions: http://66-rpm.com/ The jacket's front cover is a photo of Swamp Dogg in the studio with Tommy Hunt circa 1968. -

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

Biography 2002

THE BLACK SORROWS Biography 2002 Joe Camilleri is an Australian legend who has given his life to music. In the mid 80s following the success of his first band, Jo Jo Zep and The Falcons, Joe Camilleri gathered together a group of musician friends and dubbed them The Black Sorrows. The band began playing for the fun of it, recording independent albums and selling them out of the boot of his car. When radio picked up the classic track, 'Mystified',The Black Sorrows really took flight. They signed to CBS and proceeded to release some of Australia's most successful albums including the multi-platinum sellers Hold On To Me, Harley & Rose and The Chosen Ones. Over the past fifteen years, The Black Sorrows have toured Australia more times than anyone can remember, played sell out shows across Europe, won the ARIA for 'Best Band' and sold more than a million albums world-wide. Joe Camilleri's songs have become part of our lives. The Sorrows' string of hits is seemingly endless: Dear Children, Country Girls, Snake Skin Shoes, Harley & Rose, The Chosen Ones, Mystified, Ain't Love The Strangest Thing, Better Times, Never Let Me Go, Chained To The Wheel, Daughters of Glory, Stir It Up, New Craze... and he's certainly not done yet. Look around the world and you have to put Joe in the same company as people like Eric Clapton and Van Morrison - legends, performers whose careers span decades, transcending all styles and fads, performers who are loved for the fact that they're obviously in it for the music. -

Barbara Ann Mejia Anderson Life Sketch

Barbara Ann Mejia Anderson Life Sketch Barbara Ann Mejia was born on March 2, 1943 to Fulgencio Lagera Mejia and Marina Hendrickson, in the Queen of Angels Hospital, Los Angeles, California. Fulgencio was born and raised in the Philippines in the little town of San Nicolas. He came to America because it was the land of opportunity. He found himself in Los Angeles, California where he met Marina. Marina was from the little town of Four Mile Kentucky. It was against the law for Filipinos to marry Caucasian women at that time in California, so they had to travel to New Mexico to be married. Fulgencio joined the army during World War II and was sent overseas shortly after Barbara’s birth. Barb was three when he returned after the war, and she had no idea who her dad was. She quickly warmed up to him and they grew very close. Barb’s mom and dad both had to work two jobs each to make ends meet. When Barb was really young, she remembered being woken up at 4:30 in the morning and her mom wrapping her up in a blanket and taking her to her “Black Mammy” as Barb called her. As she grew up, a neighbor down the street watched her while her parents were at work. When Barb was young, she had a cat named Lucky. She loved her cat and it followed her wherever she went around the neighborhood. One day Lucky got into a fight with another cat, and her luck ran out. Barb and her friends buried her in a shoebox near the railroad tracks. -

Record World

record tWODedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Music & Record Industry x09664I1Y3 ONv iS Of 311VA ZPAS 3NO2 ONI 01;01 3H1 June 21, 1970 113N8V9 NOti 75c - In the opinion of the eUILIRS,la's wee% Tne itmuwmg diCtie SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK EPIC ND ARMS CAN EVER HOLD YOU CORBYVINTON Kenny Rogers and the First Mary Hopkin sings Doris Nilsson has what could be Bobby Vinton gets justa Edition advise the world to Day'sphilosophicaloldie, his biggest, a n dpossibly littlenostalgicwith"No "TellItAll Brother" (Sun- "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever hisbest single,a unique Arms Can Ever Hold You" beam, BMI), and it's bound WillBe, WillBe)" (Artist, dittyofhis own devising, (Gil, BMI),whichsounds tobe theirlatestsmash ASCAP), her way (A p p le "Down to the Valley" (Sun- just right for the summer- (Reprise 0923). 1823). beam, BM!) (RCA 74-0362). time (Epic 5-10629). SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK SORRY SUZANNE (Jan-1111 Auto uary, Embassy BMI) 4526 THE GLASS BOTTLE Booker T. & the M. G.'s do Canned Heat do "Going Up The Glass Bottle,a group JerryBlavat,Philly'sGea something just alittledif- the Country" (Metric, BMI) ofthreeguysandthree for with the Heater,isal- ferent,somethingjust a astheydo itin"Wood- gals, introduce themselves ready clicking with "Tasty littleliltingwith"Some- stock," and it will have in- with "Sorry Suzanne" (Jan- (To Me),"whichgeators thing" (Harrisongs, BMI) creasedmeaningto the uary, BMI), a rouser (Avco andgeatoretteswilllove (Stax 0073). teens (Liberty 56180). Embassy 4526). (Bond 105). ALBUM PICKS OF THE WEEK DianaRosshasherfirst "Johnny Cash the Legend" "The Me Nobody Knows" "The Naked Carmen" isa solo album here, which is tributed in this two -rec- isthe smash off-Broadway "now"-ized versionofBi- startsoutwithherfirst ord set that includes' Fol- musical adaptation of the zet's timeless opera. -

Country Christmas ...2 Rhythm

1 Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 10. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 10th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 10. Janu ar 2005 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. day 10th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken wir uns für die gute mers for their co-opera ti on in 2004. It has been a Zu sam men ar beit im ver gan ge nen Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY CHRISTMAS ..........2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................86 COUNTRY .........................8 SURF .............................92 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............25 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............93 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......25 PSYCHOBILLY ......................97 WESTERN..........................31 BRITISH R&R ........................98 WESTERN SWING....................32 SKIFFLE ...........................100 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................32 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............100 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................33 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........33 POP.............................102 COUNTRY CANADA..................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................108 COUNTRY -

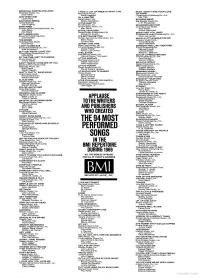

Billboard 1970-06-06-OCR-Page-0081

ABRAHAM, MARTIN AND JOHN I TAKE A LOT OF PRIDE IN WHAT I AM RUBY, DONT TAKE YOUR LOVE Roznique Music, Inc. Blue Book Music TO TOWN Dick Holler Merle Haggard Cedarwood Publishing Co., Inc. AND WHEN I DIE I'M A DRIFTER Mel Tillis Laura Nyro Detail Music, Inc. RUNNING BEAR BAD MOON RISING Bobby Goldsboro Big Bopper Music Co. Jondora Music IN THE GHETTO J. P. Richardson John Fogerty B -n -B Music, Inc. SCARBOROUGH FAIR BORN FREE Elvis Presley Music, Inc. Charing Cross Music Screen Gems- Columbia Music, Inc. Mac Davis s John Barry IN THE YEAR 2525 Arthur Garfunkel Don Black Zerlud Music Enterprises Ltd. SINCE I MET YOU, BABY BOTH SIDES NOW Richard S. Evans Progressive Music PublishingCO., Inc. Siquomb Publishing Corp. IT'S GETTING BETTER Ivory Joe Hunter Joni Mitchell Screen Gems -Columbia Music, Inc. SMILE A LITTLE SMILE FOR ME THE BOXER Barry Mann Janua Charing Music Cynthia Weil Tony Macaulay Simoose JOHNNY ONE TIME Geoff Stephens A BOY NAMED SUE Blue Crest Music, Inc. SOMEDAY WELL BE TOGETHER Evil Eye Publishing Co., Inc. Hill and Range Songs, Inc. Fuqua Publishing Co. Sher Silverstein Dallas Harvey Fuqua Leo Owens Bristol BUT YOU KNOW I LOVE YOU Johnny First Edition Productions. Inc. THE LETTER Robert L. Beavers Mike Settle Earl Barton Music, Inc. SON OF A PREACHER MAN Wayne Carson Thompson Tree Publishing Co., Inc. BY THE TIME I GET TO PHOENIX Rivers Music Co. LITTLE ARROWS John Hurley Jimmy Webb Duchess Music Corp. Ronnie Wilkins Albert Hammond STRUT. CANT TAKE MY EYES OFF OF YOU Mike Hazelwood SOULFUL Seasons Four Music Corp. -

THE COUNTRY DANCER Is Published Twice a Year

The magazine of Calendar of Events THE COUNTRY DANCE SOCIETY OF AMERICA EDITOR March 25, 1961 SQUARE DANCE - DICK FORSCHER & CLIFF BULLARD THE May Gadd (in cooperation with the McBurney YMCA), New York C.D.S. ASSISTANT EDITORS April or May C.D.S. THEATER BENEFIT, New York. Details counTRY A.C. King Diana Lockard Maxwell Reiskind to be announced. DAnCER CONTRIBUTING EDITORS April 6 - 8 26th ANNUAL MOUNTAIN FOLK FESTIVAL, Berea, Penn Elizabeth Schrader Evelyn K. Wells Ky. The Festival is affiliated with the J. Donnell Tilghman Roberta Yerkes Country Dance Society o! America. April 14 - 16 C.D.S. SPRING HOUSE PARTY WEEKEND, Hudson ART EDITOR Guild Farm, Andover, New Jersey. Genevieve Shimer April 29 tentative C.D.S. SPRING FrnTIVAL in New York THE COUNTRY DANCER is published twice a year. Subscription is June 2.3 - 26 DANCE WEEKEND at PII{E)iOODS, Boston C.D.S. by membership in the Country Dance Society of America (annual Centre. dues $5, educational institutions and libraries $3.) Inquiries and subscriptions should be sent to the Secretary, Country Dance August 6 - 20 PllmUOODS CAMP: 'lWO DANCE WEEKS, National Society of America, 55 Christopher Street, New York 14, N.Y. C.D.S., Buzzards Bay, Mass. Tel: ALgonquin 5-8895. August 20 - 27 PIN»>OODS CAMP: FOLK MUSIC AND ~ORDER WEEK, Copyright 1961 by the Country Dance Society Inc. National C.D.S., Buzzards Bay, Mass. , Table of Contents lll@llll§lll§lll§lll§lll§lll§lll§ lll§lll§lll§lll§lll§lll§ Page PICTURE CREDITS By Gloria Berchielli, New York: Jack-in-the Calendar of Events •••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 Green, p.8. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

The Beach Boys 100.Xlsx

THE BEACH BOYS 100 Rank Songs 1 Good Vibrations 2 California Girls 3 God Only Knows 4 Caroline No 5 Don't Worry Baby 6 Fun Fun Fun 7 I Get Around 8 Surfin' USA 9 Til I Die 10 Wouldn't It Be Nice 11 I Just Wasn't Made for These Times 12 Warmth of the Sun 13 409 14 Do You Remember 15 A Young Man is Gone 16 When I Grow Up 17 Come Go With Me 18 Girl from New York City 19 I Know There's an Answer 20 In My Room 21 Little Saint Nick 22 Forever 23 Surfin' 24 Dance Dance Dance 25 Let Him Run Wild 26 Darlin' 27 Rock & Roll to the Rescue 28 Don't Back Down 29 Hang on to your Ego 30 Sloop John B 31 Wipeout (w/ The Fat Boys) 32 Wild Honey 33 Friends 34 I'm Waiting for the Day 35 Shut Down 36 Little Deuce Coupe 37 Vegetables 38 Sail On Sailor 39 I Can Hear Music 40 Heroes & Villains 41 Pet Sounds 42 That's Not Me 43 Custom Machine 44 Wendy 45 Breakaway 46 Be True to Your School 47 Devoted to You 48 Don't Talk 49 Good to My Baby 50 Spirit of America 51 Let the Wind Blow THE BEACH BOYS 100 52 Kokomo 53 With Me Tonight 54 Cotton Fields 55 In the Back of My Mind 56 We'll Run Away 57 Girl Don't Tell Me 58 Surfin' Safari 59 Do You Wanna Dance 60 Here Today 61 A Time to Live in Dreams 62 Hawaii 63 Surfer Girl 64 Rock & Roll Music 65 Salt Lake City 66 Time to Get Alone 67 Marcella 68 Drive-In 69 Graduation Day 70 Wonderful 71 Surf's Up 72 Help Me Rhonda 73 Please Let Me Wonder 74 You Still Believe in Me 75 You're So Good to Me 76 Lonely Days 77 Little Honda 78 Catch a Wave 79 Let's Go Away for Awhile 80 Hushabye 81 Girls on the Beach 82 This Car of Mine 83 Little Girl I Once Knew 84 And Your Dreams Come True 85 This Whole World 86 Then I Kissed Her 87 She Knows Me Too Well 88 Do It Again 89 Wind Chimes 90 Their Hearts Were Full of Spring 91 Add Some Music to Your Day 92 We're Together Again 93 That's Why God Made Me 94 Kiss Me Baby 95 I Went to Sleep 96 Disney Girls 97 Busy Doin' Nothin' 98 Good Timin' 99 Getcha Back 100 Barbara Ann.