'Squatting Is a Part of the Housing Movement'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Vision for Social Housing

Building for our future A vision for social housing The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing Building for our future: a vision for social housing 2 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Contents Contents The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing For more information on the research that 2 Foreword informs this report, 4 Our commissioners see: Shelter.org.uk/ socialhousing 6 Executive summary Chapter 1 The housing crisis Chapter 2 How have we got here? Some names have been 16 The Grenfell Tower fire: p22 p46 changed to protect the the background to the commission identity of individuals Chapter 1 22 The housing crisis Chapter 2 46 How have we got here? Chapter 3 56 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 3 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 4 The consequences of the decline p56 p70 Chapter 4 70 The consequences of the decline Chapter 5 86 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 90 Reforming social renting Chapter 7 Chapter 5 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 Reforming social renting 102 Reforming private renting p86 p90 Chapter 8 112 Building more social housing Recommendations 138 Recommendations Chapter 7 Reforming private renting Chapter 8 Building more social housing Recommendations p102 p112 p138 4 Building for our future: a vision for social housing 5 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Foreword Foreword Foreword Reverend Dr Mike Long, Chair of the commission In January 2018, the housing and homelessness charity For social housing to work as it should, a broad political Shelter brought together sixteen commissioners from consensus is needed. -

Beginnings and Endings in Films, Film and Film Studies

Beginnings and Endings in Films, Film and Film Studies Beginnings and Endings in Films, Film and Film Studies, University of Warwick, 13th June 2008 A report by Martin Zeller, University of York, UK This conference, organised by Tom Hughes and James MacDowell (both of University of Warwick), examined the beginnings and endings of individual films and structures of beginnings and endings in films more generally, as well as notions of beginning and ending in film studies as a discipline. With such a wide remit it is not surprising that links between the various presentations were sometimes difficult to establish. However, the wide variety of approaches to the topic ensured lively discussions. The tone for the day was set by the keynote paper delivered by Warwick's own V. F. Perkins. Examining beginnings and endings in the genre of 'multi-story' (or portmanteau) movies, Perkins elucidated the various methods used to make the author the focus of these multi-stranded narratives. Drawing on the literary cachet of their source texts, Quartet, Full House and Le Plaisir make Maugham, O. Henry and Maupassant the respective loci around which their stories revolve. Pointing out that authorial intrusions were, with the exception of Le Plaisir, used only at the beginnings of such films, Perkins suggested the possibility of a largely unexplored narrative technique available in returning to the author at the close of a film. However, it was Professor Perkin's call for, 'an aesthetics of the quite good, of the satisfactorily effective, as well as the extremes: the abject and the sublime,' that seemed to resonate most with the delegates and to become a touchstone for the day's later discussions. -

Kennington Parkpark Thethe Birthplacebirthplace Ofof People’Speople’S Democracydemocracy

KenningtonKennington ParkPark TheThe BirthplaceBirthplace ofof People’sPeople’s DemocracyDemocracy StefanStefan SzczelkunSzczelkun KenningtonKennington ParkPark TheThe BirthplaceBirthplace ofof People’sPeople’s DemocracyDemocracy StefanStefan SzczelkunSzczelkun past tense Published by past tense Originally published 1997. Second edition 2005. This (third) edition 2018. past tense c/o 56a Infoshop 56 Crampton Street, London. SE17 3AE email: [email protected] More past tense texts and other material can be f ound at http://www.past-tense.org.uk http://pasttenseblog.wordpress.com https: twitter.com/@_pasttense_ https: www.facebook.com/pastensehistories The Birthplace of People’s Democracy A short one hundred and fifty years ago Kennington Common, later to be renamed Kennington Park, was host to a historic gathering which can now be seen as the birth of modern British democracy. In reaction to this gathering, the great Chartist rally of 10th April 1848, the common was forcibly enclosed and the Victorian Park was built to occupy the site. History is not objective truth. It is a selection of some facts from a mass of evidences to construct a particular view, which inevitably, reflects the ideas of the historian and their social milieu. The history most of us learnt in school left out the stories of most of the people who lived and made that history. If the design of the Victorian park means anything it is a negation of such a people’s history: an enforced amnesia of what the real Kennington Common, looking South, in 1839. On the right is the Horns Tavern; in the distance on the left is St. Marks Church. 1 importance of this space is about. -

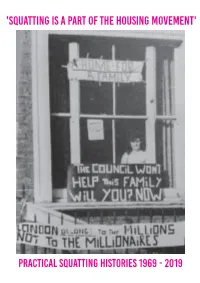

'Squatting Is a Part of the Housing Movement'

'Squatting Is A Part OF The HousinG Movement' PRACTICAL SQUATTING HISTORIES 1969 - 2019 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘...I learned how to crack window panes with a hammer muffled in a sock and then to undo the catch inside. Most houses were uninhabit- able, for they had already been dis- embowelled by the Council. The gas and electricity were disconnected, the toilets smashed...Finally we found a house near King’s Cross. It was a disused laundry, rather cramped and with a shopfront window...That night we changed the lock. Next day, we moved in. In the weeks that followed, the other derelict houses came to life as squatting spread. All the way up Caledonian Road corrugated iron was stripped from doors and windows; fresh paint appeared, and cats, flow- erpots, and bicycles; roughly printed posters offered housing advice and free pregnancy testing...’ Sidey Palenyendi and her daughters outside their new squatted home in June Guthrie, a character in the novel Finsbury Park, housed through the ‘Every Move You Make’, actions of Haringey Family Squatting Association, 1973 Alison Fell, 1984 Front Cover: 18th January 1969, Maggie O’Shannon & her two children squatted 7 Camelford Rd, Notting Hill. After 6 weeks she received a rent book! Maggie said ‘They might call me a troublemaker. Ok, if they do, I’m a trouble maker by fighting FOR the rights of the people...’ 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘Some want to continue living ‘normal lives,’ others to live ‘alternative’ lives, others to use squatting as a base for political action. -

Me, Myself & Mine: the Scope of Ownership

ME, MYSELF & MINE The Scope of Ownership _________________________________ PETER MARTIN JAWORSKI _________________________________ May, 2012 Committee: Fred Miller (Chair) David Shoemaker, Steven Wall, Daniel Jacobson, Neil Englehart ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is an attempt to defend the following thesis: The scope of legitimate ownership claims is much more narrow than what Lockean liberals have traditionally thought. Firstly, it is more narrow with respect to the particular claims that are justified by Locke’s labour- mixing argument. It is more difficult to come to own things in the first place. Secondly, it is more narrow with respect to the kinds of things that are open to the ownership relation. Some things, like persons and, maybe, cultural artifacts, are not open to the ownership relation but are, rather, fit objects for the guardianship, in the case of the former, and stewardship, in the case of the latter, relationship. To own, rather than merely have a property in, some object requires the liberty to smash, sell, or let spoil the object owned. Finally, the scope of ownership claims appear to be restricted over time. We can lose our claims in virtue of a change in us, a change that makes it the case that we are no longer responsible for some past action, like the morally interesting action required for justifying ownership claims. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Much of this work has benefited from too many people to list. However, a few warrant special mention. My committee, of course, deserves recognition. I’m grateful to Fred Miller for his many, many hours of pouring over my various manuscripts and rough drafts. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Squatting – the Real Story

Squatters are usually portrayed as worthless scroungers hell-bent on disrupting society. Here at last is the inside story of the 250,000 people from all walks of life who have squatted in Britain over the past 12 years. The country is riddled with empty houses and there are thousands of homeless people. When squatters logically put the two together the result can be electrifying, amazing and occasionally disastrous. SQUATTING the real story is a unique and diverse account the real story of squatting. Written and produced by squatters, it covers all aspects of the subject: • The history of squatting • Famous squats • The politics of squatting • Squatting as a cultural challenge • The facts behind the myths • Squatting around the world and much, much more. Contains over 500 photographs plus illustrations, cartoons, poems, songs and 4 pages of posters and murals in colour. Squatting: a revolutionary force or just a bunch of hooligans doing their own thing? Read this book for the real story. Paperback £4.90 ISBN 0 9507259 1 9 Hardback £11.50 ISBN 0 9507259 0 0 i Electronic version (not revised or updated) of original 1980 edition in portable document format (pdf), 2005 Produced and distributed by Nick Wates Associates Community planning specialists 7 Tackleway Hastings TN34 3DE United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1424 447888 Fax: +44 (0)1424 441514 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nickwates.co.uk Digital layout by Mae Wates and Graphic Ideas the real story First published in December 1980 written by Nick Anning by Bay Leaf Books, PO Box 107, London E14 7HW Celia Brown Set in Century by Pat Sampson Piers Corbyn Andrew Friend Cover photo by Union Place Collective Mark Gimson Printed by Blackrose Press, 30 Clerkenwell Close, London EC1R 0AT (tel: 01 251 3043) Andrew Ingham Pat Moan Cover & colour printing by Morning Litho Printers Ltd. -

Table of Contents Perspectives on Anarchist Theory

Table of Contents Introduction 2 Maia Ramnath Atmospheric Dialectics 8 Javier Sethness The Climate Crisis or the Crisis of Climate Politics? 26 perspectives Andre Pusey & Bertie Russell All Power to the People 48 on anarchist Lara Messersmith-Glavin theory Movements for Climate Action 56 Brian Tokar v.12 n.2 What We’re Reading 76 fall 2010 Cindy Crabb, John Duda, & Joshua Stevens Editorial Collective: Lara Messersmith-Glavin, Paul About the Illustrations 80 Messersmith-Glavin, and Maia Call for Submissions 81 Ramnath. Anarchist Interventions 82 Layout & Cover Design: Josh About the IAS 84 MacPhee. Perspectives on Anarchist Theoryis a publication of the Institute for Anarchist Studies (IAS). The views expressed here do not necessarily re- flect the IAS. Contact us at perspectivesmagazine@ Special Thanks: Josh MacPhee, the googlegroups.com. New articles, many artists from Justseeds, Jon Keller, not contained in our print edition, are David Combs, Cindy Crabb, John continually posted on line at our website. Duda, Joshua Stevens, AK Press, and You can see them at Anarchiststudies.org, Charles at Eberhardt Press. just look under “Perspectives.” “The non-sustainability and bankruptcy of the ruling world order is fully evident. The need for alternatives has never been stronger....As we face the double closure of spaces by corporate globalisation and militarised police states, by economic fascism aided by po- litical fascism, our challenge is to reclaim our freedoms and the freedoms of our fellow beings.... At the heart of building alternatives and localising economic and political systems is the recovery of the commons and the reclaiming of community. Rights to natural resources are natural rights. -

Nonlinearity, Autonomy and Resistant Law

Draft - in Webb, T. and Wheatley, S. (Eds.) Complexity Theory & Law: Mapping an Emergent Jurisprudence, Law, Science and Society Series (Routledge, Forthcoming) 11 Nonlinearity, autonomy and resistant law Lucy Finchett-Maddock* It can be a little difficult to plot a timeline of social centres when you’re dealing outside of linear time. – Interviewee from rampART collective, 2009 in Finchett-Maddock (2016, p. 168) This chapter argues that informal and communal forms of law, such as that of social centres, occupy and enact a form of spatio-temporal ‘nonlinear informality’, as opposed to a reified linearity of state law that occurs as a result of institutionalising processes of private property. Complexity theory argues the existence of both linear and nonlinear systems, whether they be regarding time, networks or otherwise. Working in an understanding of complexity theory framework to describe the spatio-temporality of law, all forms of law are argued as nonlinear, dependent on the role of uncertainty within supposedly linear and nonlinear systems and the processes of entropy in the emergence of law. ‘Supposedly’ linear, as in order for state law to assert its authority, it must become institutionalised, crystallising material architectures, customs and symbols that we know and recognise to be law. Its appearance is argued as linear as a result of institutionalisation, enabled by the elixir of individual private property and linear time as the congenital basis of its authority. But linear institutionalisation does not account for the role of uncertainty (resistance or resistant laws) within the shaping of law and demonstrates state law’s violent totalitarianism through institutionalising absolute time. -

Making Space

Alternative radical histories and campaigns continuing today. Sam Burgum November 2018 Property ownership is not a given, but a social and legal construction, with a specific history. Magna Carta (1215) established a legal precedent for protecting property owners from arbitrary possession by the state. ‘For a man’s home is his ASS Archives ASS castle, and each man’s home is his safest refuge’ - Edward Coke, 1604 Charter of the Forest (1217) asserted the rights of the ‘commons’ (i.e. propertyless) to access the 143 royal forests enclosed since 1066. Enclosure Acts (1760-1870) enclosed 7million acres of commons through 4000 acts of parliament. My land – a squatter fable A man is out walking on a hillside when suddenly John Locke (1632-1704) Squatting & Trespass Context in Trespass & Squatting the owner appears. argued that enclosure could ‘Get off my land’, he yells. only be justified if: ‘Who says it’s your land?’ demands the intruder. • ‘As much and as good’ ‘I do, and I’ve got the deeds to prove it.’ was left to others; ‘Well, where did you get it from?’ ‘From my father.’ • Unused property could be ‘And where did he get it from?’ forfeited for better use. ‘From his father. He was the seventeenth Earl. The estate originally belonged to the first Earl.’ This logic was used to ‘And how did he get it?’ dispossess indigenous people ‘He fought for it in the War of the Roses.’ of land, which appeared Right – then I’ll fight you for it!’ ‘unused’ to European settlers. 1 ‘England is not a Free people till the poor that have no land… live as Comfortably as the landlords that live in their inclosures.’ Many post-Civil war movements and sects saw the execution of King Charles as ending a centuries-long Norman oppression. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THIS COULD ONLY BE HAPPENING HERE: PLACE AND IDENTITY IN GAINESVILLE’S ZINE COMMUNITY By FIONA E STEWART-TAYLOR A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 Fiona E. Stewart-Taylor To the Civic Media Center and all the people in it ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank, first, my committee, Dr. Margaret Galvan and Dr. Anastasia Ulanowicz. Dr. Galvan has been a critical reader, engaged teacher, and generous with her expertise, feedback, reading lists, and time. This thesis has very much developed out of discussions with her about the state of the field, the interventions possible, and her many insights into how and why to write about zines in an academic context have guided and shaped this project from the start. Dr. Ulanowicz is also a generous listener and a valuable reader, and her willingness to enter this committee at a late stage in the project was deeply kind. I would also like to thank Milo and Chris at the Queer Zine Archive Project for an incredible residency during which, reading Minneapolis zines reviewing drag revues, I began to articulate some of my ideas about the importance of zines to build community in physical space, zines as living interventions into community as well as archival memory. Chris and Milo were unfailingly welcoming, friendly, and generous with their time, expertise, and long memories, as well as their vegan sloppy joes. QZAP remains an inspiration for my own work with the Civic Media Center. -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev.