16786 for the Sake of the Choir 3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

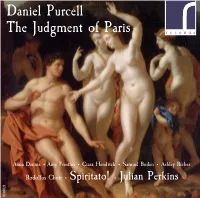

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

Czech Music Culture in London and Post-1989 Developments in Czechoslovakia at the Time

International Journal of Arts and Commerce ISSN 1929-7106 www.ijac.org.uk CZECH MUSIC CULTURE IN LONDON AND POST-1989 DEVELOPMENTS IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA AT THE TIME Markéta Koutná Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, Filozofická Fakulta, Katedra muzikologie Czech Republic E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The study deals with Czech-London musical relations, particularly Czech music culture in London within the context of cultural, social and political change in 1989. An analysis of the opera, chamber music, and symphonic production of Czech music in London between 1984 and 1994 identifies how and whether the Czechoslovak Velvet Revolution affected the firm position that Czech music culture had held in the capital of the United Kingdom. Key words: Czech musical culture, London, emigration, composers, the Velvet Revolution, 1989 The musical relations between the Czechs and London represent an important current issue. As the capital of the United Kingdom, London naturally takes the lead within the British cultural scene. With its population, budget, and institutional capacities, it is one of the world’s major social and cultural centres, and thanks to the high interest of London-based institutions in Czech music, it is also one of the world's top producers of Czech music. The current research examines how, if at all, the events of November 1989 influenced the position of Czech musical culture in London and the relationship between Czech and London musicians. I became interested in this issue while researching data for my dissertation on Czech musical culture in London.1 Using the specific example of interpretations of Czech opera, chamber music and 1 The study is a part of the student grant project IGA_FF_2015_024 Influence of the Velvet Revolution on Czech Musical Culture in London and all the data used in the study draw on the author’s research for her dissertation Czech Musical Culture in London Between 1984 and 1994. -

Abschlussprogramm Master Heft

MASTER ALTE MUSIK - HISTORISCHE TROMPETE Masterabschluss Programm Thomas Neuberth STAATLICHE HOCHSCHULE FÜR MUSIK TROSSINGEN - 14. & 15. Juli 2017 Teil I - 14. Juli 2017 Georg Philipp Telemann 1681-1767 Concerto à 3 ex F William Corbett ca. 1680-1748 Sonata op. 3 Nr. 1 D-Dur (Klausur) Pavel Josef Vejvanovsky ca. 1640-1693 Sonata à 4 Bemollis Tobias Volckmar 1678-1756 Schmücket das Fest mit Maien Gottfried Keller ca. 1650-1704 Sonate Nr. II D-Dur Johann Rosenmüller 1619-1684 O Felicissimus Paradysi Aspectus !2 Teil II - 15. Juli 2017 Christoph Förster 1693-1745 Concerto D-Dur Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber 1644-1704 Sonata Tam Aris Quam Aulis Servientes Nr. I C-Dur Alessandro Melani ca. 1639-1703 Sonata à 5 Pavel Josef Vejvanovsky ca. 1640-1693 Serenada 3 Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto à 3 ex F Georg Philipp Telemann „Ich habe mich nun von so vielen Jahren her ganz marode (1681-1767) war tatsächlich melodiert und etliche tausend mal abgeschrieben wie andere e i n e r d e r p r o d u k t i v s t e n mit mir.“ Dies gesteht Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) auf Komponisten seiner Zeit. Das dem Zenith seiner Karriere Carl Heinrich Graun, dem gilt für seine Zeit als Organist in Hofkapellmeister Friedrichs II. in Berlin. Das hanseatische Leipzig und Sorau (1704-1708), Understatement bedient und ironisiert zugleich das Etikett vom als Konzertmeister in Eisenach „Vielschreiber“, das dem Kantor am Hamburger Johanneum und (1708-1712), als Musikdirektor in Musikdirektor für die fünf Hauptkirchen der Stadt heute gern Frankfurt (1712-1721) und als angehängt wird. -

November 2020 Chamber Music Series I

Chamber Music Series Harmonies with Harpsichord | November 7th, 2020 Program Notes by Anna Norris HANDEL Suite in D major HWV 341 George Frideric Handel has always been a composer's composer. For all that he was popular with the public during his lifetime and is still popular (for at least a few of his works!) to the present day, it is the esteem that other great composers of the past hold him in that truly gives a glimpse of his character. "Handel was the greatest composer that ever lived," wrote Beethoven; "I would uncover my head and kneel before his tomb." Once, when Haydn received a compliment on the quality of his recitatives, he brushed it off with, "Ah, [the recitative] Deeper and Deeper in [Handel's] Jephtha is far beyond that!" Mozart said that "Handel understands affect better than any of us. When he chooses, he strikes like a thunder bolt." One of Handel's other notable qualities, which was perhaps better-understood by his fellow composers who experienced the pressures of producing works explicitly intended to please patrons, was his looseness and expansiveness with regards to which works could truly be said to have been written "by" him. Even in comparison to the norms of the era, Handel's propensity for borrowing and remixing both his own and others' works was prodigious; modern musicologist Richard Taruskin has summarized him as "the champion of all parodists." Copyright law, of course, was in its very infancy when Handel was an established middle-aged composer, so the idea of "intellectual property" tying one specific work to one specific person had no presence in his mind the way it does in our modern consciousness, with all of our pesky ideas of authorship and ownership. -

Introduction

IV Introduction Gottfried Finger was born in 1655 in Olmütz in Mo- Flassig, attracted attention:3 In Sünching Castle, lo- ravia (today Olomouc, Czech Republic). Very little cated near Regensburg, an extensive manuscript is known about his career in Moravia, but it is quite with works for viola da gamba was found.4 It con- certain that he was a viola da gamba player in the sists of two part books, bound in leather, with the renowned ensemble of Bishop Liechtenstein- inscription VIOLA DI GAMB: i and ii, respectively. Castelcorno, since Finger’s viol music displays the The collection is anonymous, but thanks to numer- influence of the famous viol and violin virtuoso ous concordances, Fred Flassig and Robert Rawson Heinrich Ignaz Biber, who was active at the were able to show that it exclusively contains works bishop’s court.1 Around the mid 1680s, Finger went by Finger, which are indeed even autographs.5 On to London, where he became a member of the re- the basis of dated concordances, it can be concluded nowned Catholic Chapel Royal in 1687. Although that the Sünching manuscript was written around King James II went into exile in 1688, Finger re- 1670, thus before Finger’s arrival in London. mained in London and began a freelance career, In the first part, the manuscript contains nineteen composing music for numerous operas, singspiele, sonatas, two intradas, and five suites for two viols. masques, instrumental suites, songs, and choral The second part is made up of seven suites for the works of which some were even published. -

The Musical Tradition of Central European Intengible Heritage

The Musical Tradition of Central European Intangible Heritage Wojciech M. Marchwica The Fryderyk Chopin Institute, Warsaw / Institute of Musicology, Jagiellonian University, Krakow (Poland) Problem with Definition Discussing the question of European heritage – at both national and pan‑national levels – we often concentrate on the material that remains, like bricks, trees, urban resources, design and art, etc. Very often, we forget about the results of spiritual or emotional results of human think‑ ing, about the intangible heritage, including music, instead paying at‑ tention mostly to visible artefacts. According to romantic aesthetics like Wilhelm Schlegel and others, music is the highest of the fine arts just because it does not need any kind of media to be perceived, and does not need any material form to transcribe an artist’s idea into any lis‑ tener’s mind. I am afraid that at the moment we have lost such an under‑ standing of art and – under the reign of “picture civilisation” – it is no longer valid. However, it is worth noticing that people most often associ‑ ate the term “heritage” with tangible and immovable heritage (mostly “monuments”). Recent research (concerning the role of “affectivity” and “time” in cultural understanding and social memory) underlines the role of feelings and intangible traces of cultural memory within the process of social self‑definition.1 I would like to describe such a small example of (Central) European cultural heritage within the area of music – to show the increasing complications that arise when defining the borders of mu‑ sical heritage, but also to find some solutions – describing the specific case of the pastorella. -

Doctor of Philosophy June 2008 the Candidate Confirms That the Work Submitted Is His Own and That Appropriate Credit Has Been Gi

THE TRIO SONATA IN RESTORATION ENGLAND (1660-1714) MIN-JUNG RANG Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music June 2008 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements benefited from During the writing of this dissertation, I have the advice and Dr Andrew Ashbee encouragement of many people. I am grateful particularly to and information Dr Nicholas Bell of the British Library who generously supplied me with like Dr Robert on the manuscripts on which I have been working. I would also to thank Thompson who allowed me to photograph his microfilms which saved much time and effort. I have I would also like to thank staff of the various libraries I visited, where been met with unfailing help and courtesy: the British Library, London; Bodleian Library, Oxford; Christ Church Library, Oxford; the Cathedral Library, Durham; and Leeds University Library. During the course of this project I have been fortunate in receiving great from support and encouragement from my family and friends. I met warm hospitality Prof Richard Rastall's family during my staying in Leeds, especially at Christmas time. I was extremely fortunate to receive much support from my parents. Without their financial support and faithful assistance, it would have been impossible for me to finish the work. -

The Recorder and Its Music at the Jacobite Courts in England And

The Recorder and its Music at the Jacobite Courts in England and France, 1685–1712 n 1649, Charles I, king of England, instrumentalists rather than singers, By David Lasocki Scotland and Ireland, was convicted including François La Riche, later a ofI high treason and executed. The famous oboist at the Dresden Court. The author writes about woodwind monarchy was abolished and a period Little is known about the reper- instruments, their history, repertory, and of republican rule called the Common- toire of this orchestra—it would have performance practices. His recent book wealth ensued—with first Oliver rehearsed and performed in private, with Richard Griscom, The Recorder: Crom well, then his son Richard, as and the royal archives were destroyed A Research and Information Guide, Lord Protector of the Common wealth. by fire in 1698. Andrew Pinnock and published by Routledge, received the 2014 At the Restoration of the monarchy Bruce Wood (see Resources at the end of Vincent H. Duckles Award from the in 1660, Charles I’s eldest son was this article) suggest that the musicians Music Library Association for the best crowned under the title Charles II. “honed their orchestral skills in the book-length bibliography or reference When he died in 1685, Charles II had court ode repertory above all.” work in music. This collaborative book, no legitimate children to succeed him No fewer than five of these now in its third edition, incorporates on the throne. The next-in-line was musicians were capable of playing the Lasocki’s annual reviews of research his younger brother James (b. -

B (S20) LISTENING LOG: E—L PETER EBEN Laudes Earliest Work

20 B♭ (S ) LISTENING LOG: E—L PETER EBEN Laudes Earliest work on the CD by Czech avant garde organist. Atonal, dissonant, but deals with recognizable motives and gestures. Somewhere there’s a Gregorian theme. There are four movements, the first is agitato. The second begins with extreme low and high pitches, loud rhythmic middle. The third has a weird mute stop. The fourth begins pianissimo, isolated notes on lowest pedals. (Mh17) Hommage à Buxtehude Good-humored toccata, then fantasy on a repeated note motif. Dissonant but light. (Mh17) Job Mammoth 43`organ work in 8 movements, each headed by a verse from Job. The strategy resembles Messiaen`s, but the music is craggier and I suspect less tightly organized. (1) Destiny: Job is stricken. Deep pedals for terror, toccata for agitation. (2) Faith: The Lord gives and takes away: Flutes sound the Gregorian Exsultet interrupted by terrible loud dissonance – agitation has turned to trudging, but ends, after another interruption, with muted Gloria. (3) Acceptance: After another outcry, Job is given a Bach chorale tune, “Wer nur den lieben Gott,” a hymn of faith – wild dissonances followed again by chorale. (4) Longing for Death: a passacaglia builds to climax and ends in whimpering ppp. (5) Despair and Resignation: Job`s questioning and outbursts of anger, followed by legato line of submission. (6) Mystery of Creation: eerie quiet chords and flutings, crescendo – rapid staccato chords, accelerando as if building anger – block chords fortissimo – solo flute question. (7) Penitance and Realization: Solo reed with ponderous pedal – chattering, hardly abject! – final bit based on Veni Creator. -

CHANDOS Early Music Eric Richmond Eric

CHANDOS early music Eric Richmond Eric Duo Dorado A Bohemian in London – Violin Sonatas by Gottfried Finger (1655 – 1730) 1 Sonata, RI 132 [GB-Lbl Add. 31466 No. 53]* 6:16 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur [Allegro] – [ ] Adagio – [] Allegro Adagio – Allegro – Adagio – [Allegro] – Adagio 3 / 2 – 6 / 8 2 Sonata, RI 119 [GB-Lbl Add. 31466 No. 7]† 7:00 in A major • in A-Dur • en la majeur – Adagio – Allegro – Adagio – 12 / 8 3 3 Sonata, RI 129 [GB-Lbl Add. 31466 No. 9]* 6:05 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur [Allegro] Adagio 3 / 2 – [Allegro] 4 Sonata, RI 125 [GB-Lbl Add. 31466 No. 45]* 8:02 in B flat major • in B-Dur • en si bémol majeur 3 / 2 6 / 8 5 Sonata, RI 124 [GB-Lbl Add. 31466 No. 46]† 5:06 in B flat major • in B-Dur • en si bémol majeur [Adagio] [Allegro] 3 / 4 [Adagio] – [ ] [Allegro] – 3 / 4 4 6 Sonata, RI 136 [GB-Lbl Add. 31466 No. 47]† 5:42 in F major • in F-Dur • en fa majeur – 12 / 8 [Allegro] – 3 / 4 – – 3 / 2 – [Presto] 7 Sonata, RI 120 [GB-Lbl Add. 31466 No. 23]* 5:37 in A major • in A-Dur • en la majeur 3 / 2 [Allegro] [Adagio] – 12 / 8 [Presto] – [Adagio] 3 / 2 6 / 8 8 Sonata, RI 122a [GB-Lbl Add. 31466 No. 14]* 6:36 in B minor • in h-Moll • en si mineur [Adagio] – [Allegro] [ ] [Adagio] – 3 / 2 5 9 Sonata, RI 118 [GB-Lbl Add. -

S Bach Festival

THE 24TH ST ANNE' 'S BACH FESTIVAL Friday 19 July 2019 at 1.05 pm LUNCHTIME CONCERT III PRELUDE TO BACH performed by members of THE CITY BACH COLLECTIVE Hazel Brooks baroque violin Poppy Walshaw wiola da gamba Dan Tidhar chamber organ appearing with kind support from White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities *** St Mary- -at-Hill Church, Lovat Lane London EC3R 8EE PERFORMERS' BIOGRAPHIES Hazel Brooks studied at Clare College, Cambridge, then went on to study the violin at the Hochschule fur Musik in Leipzig and the Guildhall School of Music in London, where she specialised in early music. Here she won the Christopher Kite Memorial Prize and the Bankers Trust Pyramid Award, and she was a finalist in the international competitions in York and Antwerp. Hazel now works regularly as a recitalist and in chamber She has given solo recitals in most major venues throughout the UK as well as in Germany, Italy, Russia and Spain. She is musical director of the City Bach Collective, frequently leads orchestras, and has released various solo CDs, .Hazel has an interest in unusual instruments, especially the viola d'amore, and is also in demand as a medieval- -fiddle specialist throughout Europe and America. After a period as an honorary fellow at the University of Southampton, Hazel is now a researcher at the University of Leeds, investigating violin music from seventeenth-century England, sponsored by White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities (WRoCAH) and the Arts & Humanities Research Council. Hazel enjoys turning dusty old manuscripts into living performances. Her ongoing collaboration with keyboard- -player David Pollock to revive early English violin sonatas has led to several ground- -breaking recordings, the latest being sonatas by Gottfried Finger on the Chandos label Poppy Walshaw read Music and Natural Sciences at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, then studied with Alexander Baillie in Bremen, Germany, gaining her postgraduate diploma with the highest possible mark. -

The Detroit Recorder Manuscript

The Detroit Recorder Manuscript (England, c. 1700) 1 David Lasoc~i Introduction attributed to Corelli in another source almost certainly not by him), the ARIOUS ITEMS RELATING TO THE illS l3. ~~~~~~~~ V tory of the recorder in Europe now pieces were written by four composers: rest in American collections. The best Gottfried Finger (nine), James Paisible known are the recorder methods and (seven), William Williams (two), and Ed It·~~E~~~~~ prints of Baroque recorder music in the Li ward Finch (one). Since few recorder play ers will know very much about these com brary of Congress and the instruments in 15.~§@~~~~~~ the Dayton C. Miller collection in the posers, I shall summarize what I have been same institution. One item that seems to able to find out about their lives. This ex have gone unreported in the literature so ercise also sheds light on the background 16.~~§~~~~~~ far is a manuscript volume ofrecorder mu of the manuscript. sic in the possession of the Detroit Public Library.2 The manuscript, a score written Example 1. Incipits of all the compositions in 17. m~~~~~~~~ in a legible hand, is entitled "Sonates pour the Detroit manuscript. une [two words crossed out] fluttes et Basse" on the front cover in a different 18·~~~Ei~~~ Ii hand. The title is misleading in two ways. 1.,& !U.s",:~.8gf1 UE'itl ('fd I IF I First, the manuscript contains not only 11. ~~~~~~Q~ sonatas for alto recorder and basso contin uo-seventeen ofthem-but also two sets l.@~~~~~~~ ofdivisions on ground basses for the same combination and a duet for alto recorders.