A New Collection of Viola D'amore Music from Late 18Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

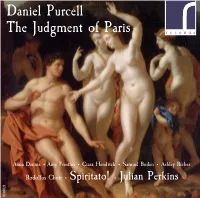

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

The Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society Text Has Been Scanned With

The Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society Text has been scanned with OCR and is therefore searchable. The format on screen does not conform with the printed Chelys. The original page numbers have been inserted within square brackets: e.g. [23]. Where necessary footnotes here run in sequence through the whole article rather than page by page and replace endnotes. The pages labelled ‘The Viola da Gamba Society Provisional Index of Viol Music’ in some early volumes are omitted here since they are up- dated as necessary as The Viola da Gamba Society Thematic Index of Music for Viols, ed. Gordon Dodd and Andrew Ashbee, 1982-, available on-line at www.vdgs.org.uk or on CD-ROM. Each item has been bookmarked: go to the ‘bookmark’ tab on the left. To avoid problems with copyright, some photographs have been omitted. Volume 31 (2003) Editorial, p. 2 Pamela Willetts Who was Richard Gibbon(s)? Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 3-17 Michael Fleming How long is a piece of string? Understanding seventeenth- century descriptions of viols. Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 18-35 David J. Rhodes The viola da gamba, its repertory and practitioners in the late eighteenth century. Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 36-63 Review Annette Otterstedt: The Viol: History of an Instrument, Thomas Munck Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 64-67 Letter (and reprinted article) Christopher Field: Hidden treasure in Gloucester Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 68-71 EDITORIAL It is strange, but unfortunately true, that to many people the term 'musicology' suggests an arid intellectual discipline far removed from the emotional immedi- acy of music. -

Baryton Trios, Vol. 2

Franz Josef Haydn Baryton trios Arranged for two clarinets and bassoon by Ray Jackendoff SCORE Volume 2 Trio 101 in Bb Trio 77 in F Trio 106 in C Franz Josef Haydn ! Baryton trios The baryton was a variation on the viola da gamba, with seven bowed strings and ten sympathetic strings. Haydn’s employer, Prince Nikolaus von Esterházy, played this instrument, and so it fell to Haydn to compose for it. Between 1761 and 1775 he wrote 126 trios for the unusual combination of baryton, viola, and cello, as well as other solo and ensemble works for baryton. As might be expected, many are rather routine. But some are quite striking, and reflect developments going on in Haydn’s composition for more customary ensembles such as the symphony and the string quartet. The six trios selected here are a sampling of the more !interesting among the trios. The trios are typically in three movements. The first movement is often slow or moderate in tempo; the other two movements are usually a fast movement and a minuet in one order or the other. Trio 96 is one of the few in a minor key; Trio 101 is unusual in having a fugal finale, !along the lines of the contemporaneous Op. 20 string quartets. In arranging these trios for two clarinets and bassoon, I have transposed all but Trio 96 down a whole step from the original key. I have added dynamics and articulations that have worked well in performance. We have found that the minuets, especially those that serve as final movements, !work better if repeats are taken in the da capo. -

Vol34-1997-1.Pdf

- ---~ - - - - -- - -- -- JOURNAL OF THE VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY OF AMERICA Volume 34 1997 EDITOR: Caroline Cunningham SENIOR EDITOR: Jean Seiler CONSULTING EDITOR: F. Cunningham, Jr. REVIEW EDITOR: Stuart G. Cheney EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Cbarteris Gordon Sandford MaryCyr Richard Taruskin Roland Hutchinson Frank Traficante Thomas G. MacCracken Ian Woodfield CONTENTS Viola cia Gamba Society of America ................. 3 Editorial Note . 4 Interview with Sydney Beck .................. Alison Fowle 5 Gender, Class, and Eighteenth-Centwy French Music: Barthelemy de Caix's Six Sonatas for Two Unaccompanied Pardessus de Viole, Part II ..... Tina Chancey 16 Ornamentation in English Lyra Viol Music, Part I: Slurs, Juts, Thumps, and Other "Graces" for the Bow ................................. Mary Cyr 48 The Archetype of Johann Sebastian Bach's Chorale Setting "Nun Komm, der Heiden Heiland" (BWV 660): A Composition with Viola cia Gamba? - R. Bruggaier ..... trans. Roland Hutchinson 67 Recent Research on the Viol ................. Ian Woodfield 75 Reviews Jeffery Kite-Powell, ed., A Performer's Guide to Renaissance Music . .......... Russell E. Murray, Jr. 77 Sterling Scott Jones, The Lira da Braccio ....... Herbert Myers 84 Grace Feldman, The Golden Viol: Method VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY OF AMERICA for the Bass Viola da Gamba, vols. 3 and 4 ...... Alice Robbins 89 253 East Delaware, Apt. 12F Andreas Lidl, Three Sonatas for viola da Chicago, IL 60611 gamba and violoncello, ed. Donald Beecher ..... Brent Wissick 93 [email protected] John Ward, The Italian Madrigal Fantasies " http://www.enteract.com/-vdgsa ofFive Parts, ed. George Hunter ............ Patrice Connelly 98 Contributor Profiles. .. 103 The Viola da Gamba Society of America is a not-for-profit national I organization dedicated to the support of activities relating to the viola •••••• da gamba in the United States and abroad. -

Czech Music Culture in London and Post-1989 Developments in Czechoslovakia at the Time

International Journal of Arts and Commerce ISSN 1929-7106 www.ijac.org.uk CZECH MUSIC CULTURE IN LONDON AND POST-1989 DEVELOPMENTS IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA AT THE TIME Markéta Koutná Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, Filozofická Fakulta, Katedra muzikologie Czech Republic E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The study deals with Czech-London musical relations, particularly Czech music culture in London within the context of cultural, social and political change in 1989. An analysis of the opera, chamber music, and symphonic production of Czech music in London between 1984 and 1994 identifies how and whether the Czechoslovak Velvet Revolution affected the firm position that Czech music culture had held in the capital of the United Kingdom. Key words: Czech musical culture, London, emigration, composers, the Velvet Revolution, 1989 The musical relations between the Czechs and London represent an important current issue. As the capital of the United Kingdom, London naturally takes the lead within the British cultural scene. With its population, budget, and institutional capacities, it is one of the world’s major social and cultural centres, and thanks to the high interest of London-based institutions in Czech music, it is also one of the world's top producers of Czech music. The current research examines how, if at all, the events of November 1989 influenced the position of Czech musical culture in London and the relationship between Czech and London musicians. I became interested in this issue while researching data for my dissertation on Czech musical culture in London.1 Using the specific example of interpretations of Czech opera, chamber music and 1 The study is a part of the student grant project IGA_FF_2015_024 Influence of the Velvet Revolution on Czech Musical Culture in London and all the data used in the study draw on the author’s research for her dissertation Czech Musical Culture in London Between 1984 and 1994. -

Abschlussprogramm Master Heft

MASTER ALTE MUSIK - HISTORISCHE TROMPETE Masterabschluss Programm Thomas Neuberth STAATLICHE HOCHSCHULE FÜR MUSIK TROSSINGEN - 14. & 15. Juli 2017 Teil I - 14. Juli 2017 Georg Philipp Telemann 1681-1767 Concerto à 3 ex F William Corbett ca. 1680-1748 Sonata op. 3 Nr. 1 D-Dur (Klausur) Pavel Josef Vejvanovsky ca. 1640-1693 Sonata à 4 Bemollis Tobias Volckmar 1678-1756 Schmücket das Fest mit Maien Gottfried Keller ca. 1650-1704 Sonate Nr. II D-Dur Johann Rosenmüller 1619-1684 O Felicissimus Paradysi Aspectus !2 Teil II - 15. Juli 2017 Christoph Förster 1693-1745 Concerto D-Dur Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber 1644-1704 Sonata Tam Aris Quam Aulis Servientes Nr. I C-Dur Alessandro Melani ca. 1639-1703 Sonata à 5 Pavel Josef Vejvanovsky ca. 1640-1693 Serenada 3 Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto à 3 ex F Georg Philipp Telemann „Ich habe mich nun von so vielen Jahren her ganz marode (1681-1767) war tatsächlich melodiert und etliche tausend mal abgeschrieben wie andere e i n e r d e r p r o d u k t i v s t e n mit mir.“ Dies gesteht Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) auf Komponisten seiner Zeit. Das dem Zenith seiner Karriere Carl Heinrich Graun, dem gilt für seine Zeit als Organist in Hofkapellmeister Friedrichs II. in Berlin. Das hanseatische Leipzig und Sorau (1704-1708), Understatement bedient und ironisiert zugleich das Etikett vom als Konzertmeister in Eisenach „Vielschreiber“, das dem Kantor am Hamburger Johanneum und (1708-1712), als Musikdirektor in Musikdirektor für die fünf Hauptkirchen der Stadt heute gern Frankfurt (1712-1721) und als angehängt wird. -

In Short Tortheater in Vienna

Cello Concerto in C major, Hob. VIIb:1 Joseph Haydn t is more than a little ironic that Haydn’s deposited in the National Museum of Prague. Isplendid Cello Concerto in C major, which The parts were uncovered there by musicol- is today one his most popular concertos, lay ogist Oldřich Pulkert as recently as 1961. in oblivion for almost two centuries. Haydn In the first movement, this work unrolls at did enter it in his Entwurf-Katalog (Draft a spacious pace, without calling attention to Catalogue), an inventory he began around the considerable virtuosity required for its ex- 1765, so the piece must have been written by ecution. Pairs of oboes and horns add body to that year at the latest. This was therefore a the tutti sections, although Haydn limits the work of the composer’s first years at the Es- accompaniment to a string orchestra when terházy Court, which makes sense given the the cello is playing. The wisdom of his deci- prominent solo-cello writing he employed sion to keep the textures light is confirmed in some of his other pieces of that time; the by later cello concertos (by other composers) well-known Symphonies Nos. 6–8 come im- in which the soloist can be seen playing but mediately to mind, as well as the Sympho- can scarcely be heard. Of course, problems nies Nos. 13, 31, 36, and 72 — all, despite their of balance between soloist and orchestra are eventual numbering, from 1765 or earlier. considerably reduced when the “symphonic” The cellist all these works were meant to forces are hardly larger than a chamber group spotlight was Joseph Franz Weigl, one of — as they were when this piece was new. -

Great Organ-Great Artists

THE GREAT ORGAN GREAT SOLO 16 Montre 61 pipes (unenclosed) 16 Quintaten 61 pipes 8 Tuba Major 61 pipes 8 Principal 61 pipes 4 Tuba Clarion 73 pipes-double trebles 8 Diapason 79 pipes- double trebles 8 Viola 61 pipes CHOIR 8 Hohl Flöte 61 pipes 16 Sanftbass 73 pipes 8 Holz Gedeckt 61 pipes 8 Viola Pomposa 73 pipes 8 Erzähler 61 pipes 8 Viola Celeste 73 pipes 8 Quintaten 12 pipes 8 Dulcet II 146 pipes 5 1/3 Quinte 61 pipes 8 Dolcan 73 pipes 4 Principal 85 pipes-double trebles 8 Dolcan Celeste 61 pipes 4 Octave 85 pipes-double trebles 8 Concert Flute 73 pipes 4 Spitzflöte 61 pipes 8 Nason Flute 73 pipes 4 Flute Couverte 61 pipes 4 Principal 73 pipes 3 1/5 Grosse Tierce 61 pipes 4 Koppelflöte 61 pipes 2 2/3 Twelfth 61 pipes 2 2/3 Rohr Nasat 61 pipes 2 Doublette 85 pipes-double trebles 2 Blockflöte 61 pipes 2 Fifteenth 61 pipes 1 3/5 Terz 61 pipes Sesquialtera II 122 pipes 11/3 Larigot 61 pipes Kleine Mixtur IV 244 pipes 1 Sifflöte 61 pipes Grande Fourniture V–VIII 368 pipes Grave Mixtur III 183 pipes Plein Jeu III–V 294 pipes Zimbel III 183 pipes Cymbel III 183 pipes 16 English Horn 73 pipes 16 Fagot 61 pipes 8 Cromorne 73 pipes 8 Clarinet 73 pipes SWELL 4 Trompete 73 pipes 16 Contra Gamba 73 pipes Tremulant 16 Bourdon 73 pipes 8 Tuba Major (Solo) 8 Geigen Prinzipal 73 pipes 4 Tuba Clarion (Solo) 8 Viole de Gambe 73 pipes 8 Viole Celeste 73 pipes PEDAL 8 Salicional 73 pipes 32 Open Bass 12 pipes 8 Voix Celeste 73 pipes 32 Contre Violone 12 pipes 8 Unda Maris II 136 pipes 16 Contre Basse 32 pipes 8 Flauto Dolce 73 pipes 16 Open Bass 32 pipes -

An Examination of the Seventeenth-Century English Lyra

An examination of the seventeenth-century English lyra viol and the challenges of modern editing Volume 1 of 2 Volume 1 Katie Patricia Molloy MA by Research University of York Music January 2015 Abstract This dissertation explores the lyra viol and the issues of transcribing the repertoire for the classical guitar. It explores the ambiguities surrounding the lyra viol tradition, focusing on the organology of the instrument, the multiple variant tunings required to perform the repertoire, and the repertoire specifically looking at the solo works. The second focus is on the task of transcribing this repertoire, and specifically on how one can make it user-friendly for the 21st-century performer. It looks at the issues of tablature, and the issues of standard notation, and finally explores the notational possibilities with the transcription, experimenting with the different options and testing their accessibility. Volume II is a transliteration of solo lyra viol works by Simon Ives from the source Oxford, Bodleian Library Music School MS F.575. It includes a biography of Simon Ives, a study of the manuscript in question and describes the editorial procedures that were chosen as a result of the investigations in volume I. 2 Contents Volume I Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 6 Declaration 7 Introduction 8 1. The use of the term ‘lyra viol’ 12 2. The organology of the lyra viol 23 3. The tuning of the instrument 38 4. The lyra viol repertoire with specific focus on the solo works 45 5. The transcription of tablature 64 6. Experimentation with notation -

Viol in Oxford Music Online Oxford Music Online

14.3.2011 Viol in Oxford Music Online Oxford Music Online Grove Music Online Viol article url: http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/music/29435 Viol [viola da gamba, gamba] (Fr. viole ; Ger. Gambe ; It. viola , viola da gamba ). A bowed string instrument with frets; in the Hornbostel-Sachs system it is classified as a bowed lute (or fiddle). It is usually played held downwards on the lap or between the legs (hence the name ‘viola da gamba’, literally ‘leg viol’). It appeared in Europe towards the end of the 15th century and subsequently became one of the most popular of all Renaissance and Baroque instruments and was much used in ensemble music ( see CONSORT and CONTINUO ). As a solo instrument it continued to flourish until the middle of the 18th century. In 18th- and 19th-century American usage the term BASS VIOL was applied to a four-string instrument of the violin family. 1. Structure. During its history the viol was made in many different sizes: pardessus (high treble), treble, alto, small tenor, tenor, bass and violone (contrabass). Only the treble, tenor and bass viols, however, were regular members of the viol consort. The pardessus de viole did not emerge until the late 17th century, and the violone – despite its appearance in the 16th century – was rarely used in viol consorts. The alto viol was rarely mentioned by theorists and there is some doubt as to how often it was used. Two small bass instruments called ‘lyra’ and ‘division’ viols were used in the performance of solo music in England ( see LYRA VIOL and DIVISION VIOL ). -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

The English Horn: Its History and Development

37 THE ENGLISH HORN: ITS HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT INTO ORCHESTRAL MUSIC THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Robert E. Stanton, B. M. Denton, Texas January, 1968 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS..................... ....... iv Chapter I. HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH HORN. ......... 1 II. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ENGLISH HORN .............. 26 III. ORCHESTRAL DEVELOPMENT . ........... 44 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............. ........ 64 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figuree Page 1. Alto pommer.. .................... 0...... 4 2. Oboe da caccia -0 . 0 0. I.. 0. 0.0 . 5 3. Tenor Oboe of Bach-Handel Period . 7 4. Hornpipe . 0. 0. *.. 0. 0. 0. 0 . 9 5. (5) Tenor Hautboy; (6) Cor Anglais (Eighteenth century).................. ......... 12 6. Cor Anglais, Curved and Angular Types, (2)and (4) - 0 . .0 .0 . .0 .0 . 13 7. Hautbois Baryton, (4) and (5) . 14 8. Vox Humana ... .. .. 16 9. Fontanelle 17 10. Bulb-bell..... ... ..... 18 11. Hunting Oboe . 20 12. Notation for Cor Anglais . 29 13. Construction of Bent Cor Anglais; (A), (B), (C) . .. 33 14. Bow-drill in use . 36 15. Cor Anglais reeds. ........ 41 16. Range of English Horn.. .... 43 17. Tenoroon 45 18. List of Bach's Use of Oboe da caccia . 47 19. Oboe da caccia Accompaniment, St. Matthew Passion 48 iv Figure Page 20. Oboe da caccia part, St. Matthew Passion...-.-......... ... 50 21. Gluck: Orfeus for Corno Inglese 53 22. Berlioz: Roman Carnival...... ...... 56 23. Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique 57 24. Wagner: Tristan and Isolde 59 25. Dvorak: New World SyMphony 60 V CHAPTER I HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH HORN The English horn has a background of historical con fusion because the instrument was built in many different shapes and was given a new name for each change of form.