Semelejohn Eccles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoughts in Advance of an Interpretation

Professor Hartmut Haenchen Thoughts in advance of an interpretation Reflections on Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro in the light of performance practice Ornaments, cadenzas, lead-ins, dynamics and other points of vocal interest Luigi Bassi1 was a member of the Prague opera company and, as such, played a major part in the overwhelming success of Don Giovanni in Prague, where he sang not only the title role in the very first performance of Mozart's dramma giocoso, but also the Count in the local première of Le nozze di Figaro. Describing a later performance of one of Mozart's operas, he wrote: “There's nothing here, there's none of the animation or freedom that the great maestro wanted in this scene. Under Guardasoni2 we never sang this number the same way in two performances running, we didn't keep such strict time but made new jokes at each performance and paid attention only to the orchestra; everything parlando and virtually improvised - that's how Mozart wanted it.” However much Mozart may have insisted on a regular beat3, he was far from demanding slavish adherence in such matters. The type of freedom described by Bassi is entirely consistent with his own description of 'tempo rubato': “Everyone is amazed that I can always keep strict time. What these people cannot grasp is that in tempo rubato in an Adagio, the left hand should go on playing in strict time. With them the right hand gives in to the rubato.”4 Applying this definition to Bassi's foregoing description, we could say that the orchestra was the “left hand” and the singer, with his freedom of approach, the right hand.5 Bassi's account also touches on all the other questions bound up with a ‘parlando’ treatment of the text, including the various liberties that could be taken, the ornaments and cadenzas sanctioned by contemporary performance practice and the 'animation' that was achieved in various ways, not least of which was the use of extremely finely differentiated dynamics. -

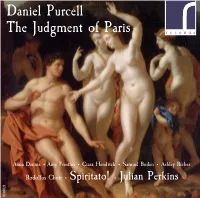

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

Lilypond Music Glossary

LilyPond The music typesetter Music Glossary The LilyPond development team ☛ ✟ This glossary provides definitions and translations of musical terms used in the documentation manuals for LilyPond version 2.23.3. ✡ ✠ ☛ ✟ For more information about how this manual fits with the other documentation, or to read this manual in other formats, see Section “Manuals” in General Information. If you are missing any manuals, the complete documentation can be found at http://lilypond.org/. ✡ ✠ Copyright ⃝c 1999–2021 by the authors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. For LilyPond version 2.23.3 1 1 Musical terms A-Z Languages in this order. • UK - British English (where it differs from American English) • ES - Spanish • I - Italian • F - French • D - German • NL - Dutch • DK - Danish • S - Swedish • FI - Finnish 1.1 A • ES: la • I: la • F: la • D: A, a • NL: a • DK: a • S: a • FI: A, a See also Chapter 3 [Pitch names], page 87. 1.2 a due ES: a dos, I: a due, F: `adeux, D: ?, NL: ?, DK: ?, S: ?, FI: kahdelle. Abbreviated a2 or a 2. In orchestral scores, a due indicates that: 1. A single part notated on a single staff that normally carries parts for two players (e.g. first and second oboes) is to be played by both players. -

Beyond Borealism

Beyond Borealism: New Perspectives on the North eds. Ian Giles, Laura Chapot, Christian Cooijmans, Ryan Foster and Barbara Tesio Norvik Press 2016 © 2016 Charlotte Berry, Laura Chapot, Marc Chivers, Pei-Sze Chow, Christian Cooijmans, Jan D. Cox, Stefan Drechsler, Ryan Foster, Ian Giles, Karianne Hansen, Pavel Iosad, Elyse Jamieson, Ellen Kythor, Shane McLeod, Hafor Medbøe, Kitty Corbet Milward, Eleanor Parker, Silke Reeploeg, Cristina Sandu, Barbara Tesio. Norvik Press Series C: Student Writing no. 3 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-909408-33-3 Norvik Press Department of Scandinavian Studies UCL Gower Street London WC1E 6BT United kingdom Website: www.norvikpress.com E-mail address: [email protected] Managing Editors: Elettra Carbone, Sarah Death, Janet Garton, C.Claire Tomson. Cover design: Sarah Diver Lang and Elettra Carbone Inside cover image: Sarah Diver Lang Layout: Elettra Carbone 2 Contents Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 12 Biographies 13 Editor Biographies 13 Contributor Biographies 15 ECHOES OF HISTORY 21 The Medieval Seal of Reynistaður 22 Stefan Drechsler ‘So Very Memorable a Matter’: Anglo-Danish History and the Encomium Emmae Reginae 41 Eleanor Parker A Similar but Different Boat Tradition: The Import of Boats from Norway to Shetland 1700 to 1872 54 Marc Chivers LINGUISTIC LIAISONS 77 Tonal Stability and Tonogenesis in (North) Germanic 78 Pavel Iosad Imperative Commands in Shetland Dialect: Nordic Origins? 96 Elyse Jamieson 3 ART AND SOCIETY 115 The Battle of Kringen -

Les Opéras De Lully Remaniés Par Rebel Et Francœur Entre 1744 Et 1767 : Héritage Ou Modernité ? Pascal Denécheau

Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Pascal Denécheau To cite this version: Pascal Denécheau. Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? : Deuxième séminaire de recherche de l’IRPMF : ”La notion d’héritage dans l’histoire de la musique”. 2007. halshs-00437641 HAL Id: halshs-00437641 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00437641 Preprint submitted on 1 Dec 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. P. Denécheau : « Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur : héritage ou modernité ? » Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Une grande partie des œuvres lyriques composées au XVIIe siècle par Lully et ses prédécesseurs ne se sont maintenues au répertoire de l’Opéra de Paris jusqu’à la fin du siècle suivant qu’au prix d’importants remaniements : les scènes jugées trop longues ou sans lien avec l’action principale furent coupées, quelques passages réécrits, un accompagnement de l’orchestre ajouté là où la voix n’était auparavant soutenue que par le continuo. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

The Fragmentation of Being and the Path Beyond the Void 2185 Copyright 1994 Kent D

DRAFT Fragment 48 THE HOUSE OF BAAL Next we will consider the house of Baal who is the twin of Agenor. Agenor means the “manly,” whereas Baal means “lord.” In Baal is Belus. Within the Judeo- Christian religious tradition, Baal is the archetypal adversary to the God of the Old Testament. No strange god, however, is depicted more wicked, immoral and abominable than the storm god Ba’al Hadad, whose cult appears to have been a great rival to Yahwism at certain times in Israel’s history. In the bible we read how the prophets of Ba’al and Yahweh persecuted and killed one another, and how the kings of Israel wavered in their attitudes to these gods, thereby provoking the jealousy of Yahweh who tolerated no other god beside him. Thus, it appears that the worship of Ba’al Hadad was a greater threat to Yahwism than that of any other god, and this fact, perhaps more than the actual character of the Ba’al cult, may be the reason for the Hebrew aversion against it. The Fragmentation of Being and The Path Beyond The Void 2185 Copyright 1994 Kent D. Palmer. All rights reserved. Not for distribution. THE HOUSE OF BAAL Whereas Ba’al became hated by the true Yahwist, Yahweh was the national god of Israel to whose glory the Hebrew Bible is written. Yahweh is also called El. That El is a proper name and not only the appelative, meaning “god” is proven by several passages in the Bible. According to the Genesis account, El revealed himself to Abraham and led him into Canaan where not only Abraham and his family worshiped El, but also the Canaanites themselves. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz

Classics & Jazz PAID Permit # 79 PRSRT STD PRSRT Late Fall 2020 U.S. Postage Aberdeen, SD Jazz New Naxos Bundle Deal Releases 3 for $30 see page 54 beginning on page 10 more @ more @ HBDirect.com HBDirect.com see page 22 OJC Bundle Deal P.O. Box 309 P.O. 05677 VT Center, Waterbury Address Service Requested 3 for $30 see page 48 Classical 50% Off beginning on page 24 more @ HBDirect.com 1/800/222-6872 www.hbdirect.com Classical New Releases beginning on page 28 more @ HBDirect.com Love Music. HBDirect Classics & Jazz We are pleased to present the HBDirect Late Fall 2020 Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz Catalog, with a broad range of offers we’re sure will be of great interest to our customers. Catalog Index Villa-Lobos: The Symphonies / Karabtchevsky; São Paulo SO [6 CDs] In jazz, we’re excited to present another major label as a Heitor Villa-Lobos has been described as ‘the single most significant 4 Classical - Boxed Sets 3 for $30 bundle deal – Original Jazz Classics – as well as a creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music.’ The eleven sale on Double Moon, recent Enlightenment boxed sets and 10 Classical - Naxos 3 for $30 Deal! symphonies - the enigmatic Symphony No. 5 has never been found new jazz releases. On the classical side, HBDirect is proud to 18 Classical - DVD & Blu-ray and may not ever have been written - range from the two earliest, be the industry leader when it comes to the comprehensive conceived in a broadly Central European tradition, to the final symphony 20 Classical - Recommendations presentation of new classical releases. -

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30Pm, Hall

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30pm, Hall The English Concert Harry Bicket conductor/harpsichord Iestyn Davies Rinaldo Jane Archibald Armida Sasha Cooke Goffredo Joélle Harvey Almirena/Siren Luca Pisaroni Argante Jakub Józef Orli ´nski Eustazio Owen Willetts Araldo/Donna/Mago Richard Haughton Richard There will be two intervals of 20 minutes following Act 1 and Act 2 Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 We appreciate that it’s not always possible to prevent coughing during a performance. But, for the sake of other audience members and the artists, if you feel the need to cough or sneeze, please stifle it with a handkerchief. Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight we welcome back Harry Bicket as delighted by the extravagant magical and The English Concert for Rinaldo, the effects as by Handel’s endlessly inventive latest instalment in their Handel opera music. And no wonder – for Rinaldo brings series. Last season we were treated to a together love, vengeance, forgiveness, spine-tingling performance of Ariodante, battle scenes and a splendid sorceress with a stellar cast led by Alice Coote. -

Module D (June 2015 Session) Page 1 of 12

SECTION A – CASE QUESTIONS Answer 1 DIPN Issued by the IRD, DIPN clarifies the IRD’s viewpoints on particular tax provisions and/or the practice of the IRD in certain given situations. It also outlines the IRD’s respective procedures in administrating relevant provisions of the IRO. Notwithstanding that DIPN has no binding force in law (BOR D54/06, para. 25), the IRD would follow, in general, what has been laid down in the DIPNs, both interpretation of tax provisions and assessing practices. BOR Decisions The BOR is an independent statutory body to determine tax appeals. Decisions made by the BOR are final with regard to the facts of a particular case. In addition, BOR’s decisions are not binding on other BOR cases. With reference to the BOR’s decisions, taxpayers can identify how the relevant provisions in the IRO are interpreted and applied in the circumstances. Local Court Cases for tax In the appeals to the Hong Kong Courts, the judges are required to decide the cases by expressing their opinion in respect of questions of law. If taxpayers or the IRD cannot agree on the interpretation of a provision in the IRO, both parties can use the appeal procedures laid down in the IRO to seek a ruling on a question of law from the Courts. In addition, the decisions of a higher court (e.g. Court of Final Appeal) bind all lower courts and the BOR, i.e. the doctrine of judicial precedent. Answer 2 Under s.4 of the IRO, officers of the IRD shall preserve secrecy with regard to all matters relating to the affairs of any person coming to his knowledge, except in the performance of his duties under the IRO. -

HANDEL Acis and Galatea

SUPER AUDIO CD HANDEL ACIS AND GALATEA Lucy Crowe . Allan Clayton . Benjamin Hulett Neal Davies . Jeremy Budd Early Opera Company CHANDOS early music CHRISTIAN CURNYN GEOR G E FRIDERICH A NDEL, c . 1726 Portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685 – 1749) © De Agostini / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library GeoRge FRIdeRIC Handel (1685–1759) Acis and Galatea, HWV 49a (1718) Pastoral entertainment in one act Libretto probably co-authored by John Gay, Alexander Pope, and John Hughes Galatea .......................................................................................Lucy Crowe soprano Acis ..............................................................................................Allan Clayton tenor Damon .................................................................................Benjamin Hulett tenor Polyphemus...................................................................Neal Davies bass-baritone Coridon ........................................................................................Jeremy Budd tenor Soprano in choruses ....................................................... Rowan Pierce soprano Early Opera Company Christian Curnyn 3 COMPACT DISC ONE 1 1 Sinfonia. Presto 3:02 2 2 Chorus: ‘Oh, the pleasure of the plains!’ 5:07 3 3 Recitative, accompanied. Galatea: ‘Ye verdant plains and woody mountains’ 0:41 4 4 Air. Galatea: ‘Hush, ye pretty warbling choir!’. Andante 5:57 5 5 [Air.] Acis: ‘Where shall I seek the charming fair?’. Larghetto 2:50 6 6 Recitative. Damon: ‘Stay, shepherd, stay!’ 0:21 7 7 Air. Damon: ‘Shepherd, what art thou pursuing?’. Andante 4:05 8 8 Recitative. Acis: ‘Lo, here my love, turn, Galatea, hither turn thy eyes!’ 0:21 9 9 Air. Acis: ‘Love in her eyes sits playing’. Larghetto 6:15 10 10 Recitative. Galatea: ‘Oh, didst thou know the pains of absent love’ 0:13 11 11 Air. Galatea: ‘As when the dove’. Andante 5:53 12 12 Duet. Acis and Galatea: ‘Happy we!’. Presto 2:48 TT 37:38 4 COMPACT DISC TWO 1 14 Chorus: ‘Wretched lovers! Fate has past’.