1.6.5 Box Plots, Quartiles, and the Median a Box Plot Summarizes a Data Set Using five Statistics While Also Plotting Unusual Observa- Tions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing Normality I) Normal Probability Plots : Look for The

Assessing Normality i) Normal Probability Plots: Look for the observations to fall reasonably close to the green line. Strong deviations from the line indicate non- normality. Normal P-P Plot of BLOOD Normal P-P Plot of V1 1.00 1.00 .75 .75 .50 .50 .25 .25 0.00 0.00 Expected Cummulative Prob Expected Cummulative Expected Cummulative Prob Expected Cummulative 0.00 .25 .50 .75 1.00 0.00 .25 .50 .75 1.00 Observed Cummulative Prob Observed Cummulative Prob The observations fall very close to the There is clear indication that the data line. There is very little indication of do not follow the line. The assumption non-normality. of normality is clearly violated. ii) Histogram: Look for a “bell-shape”. Severe skewness and/or outliers are indications of non-normality. 5 16 14 4 12 10 3 8 2 6 4 1 Std. Dev = 60.29 Std. Dev = 992.11 2 Mean = 274.3 Mean = 573.1 0 N = 20.00 0 N = 25.00 150.0 200.0 250.0 300.0 350.0 0.0 1000.0 2000.0 3000.0 4000.0 175.0 225.0 275.0 325.0 375.0 500.0 1500.0 2500.0 3500.0 4500.0 BLOOD V1 Although the histogram is not perfectly There is a clear indication that the data symmetric and bell-shaped, there is no are right-skewed with some strong clear violation of normality. outliers. The assumption of normality is clearly violated. Caution: Histograms are not useful for small sample sizes as it is difficult to get a clear picture of the distribution. -

Fan Chart: Methodology and Its Application to Inflation Forecasting in India

W P S (DEPR) : 5 / 2011 RBI WORKING PAPER SERIES Fan Chart: Methodology and its Application to Inflation Forecasting in India Nivedita Banerjee and Abhiman Das DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND POLICY RESEARCH MAY 2011 The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) introduced the RBI Working Papers series in May 2011. These papers present research in progress of the staff members of RBI and are disseminated to elicit comments and further debate. The views expressed in these papers are those of authors and not that of RBI. Comments and observations may please be forwarded to authors. Citation and use of such papers should take into account its provisional character. Copyright: Reserve Bank of India 2011 Fan Chart: Methodology and its Application to Inflation Forecasting in India Nivedita Banerjee 1 (Email) and Abhiman Das (Email) Abstract Ever since Bank of England first published its inflation forecasts in February 1996, the Fan Chart has been an integral part of inflation reports of central banks around the world. The Fan Chart is basically used to improve presentation: to focus attention on the whole of the forecast distribution, rather than on small changes to the central projection. However, forecast distribution is a technical concept originated from the statistical sampling distribution. In this paper, we have presented the technical details underlying the derivation of Fan Chart used in representing the uncertainty in inflation forecasts. The uncertainty occurs because of the inter-play of the macro-economic variables affecting inflation. The uncertainty in the macro-economic variables is based on their historical standard deviation of the forecast errors, but we also allow these to be subjectively adjusted. -

Finding Basic Statistics Using Minitab 1. Put Your Data Values in One of the Columns of the Minitab Worksheet

Finding Basic Statistics Using Minitab 1. Put your data values in one of the columns of the Minitab worksheet. 2. Add a variable name in the gray box just above the data values. 3. Click on “Stat”, then click on “Basic Statistics”, and then click on "Display Descriptive Statistics". 4. Choose the variable you want the basic statistics for click on “Select”. 5. Click on the “Statistics” box and then check the box next to each statistic you want to see, and uncheck the boxes next to those you do not what to see. 6. Click on “OK” in that window and click on “OK” in the next window. 7. The values of all the statistics you selected will appear in the Session window. Example (Navidi & Monk, Elementary Statistics, 2nd edition, #31 p. 143, 1st 4 columns): This data gives the number of tribal casinos in a sample of 16 states. 3 7 14 114 2 3 7 8 26 4 3 14 70 3 21 1 Open Minitab and enter the data under C1. The table below shows a portion of the entered data. ↓ C1 C2 Casinos 1 3 2 7 3 14 4 114 5 2 6 3 7 7 8 8 9 26 10 4 Now click on “Stat” and then choose “Basic Statistics” and “Display Descriptive Statistics”. Click in the box under “Variables:”, choose C1 from the window at left, and then click on the “Select” button. Next click on the “Statistics” button and choose which statistics you want to find. We will usually be interested in the following statistics: mean, standard error of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, range, first quartile, median, third quartile, interquartile range, mode, and skewness. -

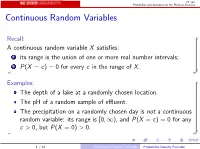

Continuous Random Variables

ST 380 Probability and Statistics for the Physical Sciences Continuous Random Variables Recall: A continuous random variable X satisfies: 1 its range is the union of one or more real number intervals; 2 P(X = c) = 0 for every c in the range of X . Examples: The depth of a lake at a randomly chosen location. The pH of a random sample of effluent. The precipitation on a randomly chosen day is not a continuous random variable: its range is [0; 1), and P(X = c) = 0 for any c > 0, but P(X = 0) > 0. 1 / 12 Continuous Random Variables Probability Density Function ST 380 Probability and Statistics for the Physical Sciences Discretized Data Suppose that we measure the depth of the lake, but round the depth off to some unit. The rounded value Y is a discrete random variable; we can display its probability mass function as a bar graph, because each mass actually represents an interval of values of X . In R source("discretize.R") discretize(0.5) 2 / 12 Continuous Random Variables Probability Density Function ST 380 Probability and Statistics for the Physical Sciences As the rounding unit becomes smaller, the bar graph more accurately represents the continuous distribution: discretize(0.25) discretize(0.1) When the rounding unit is very small, the bar graph approximates a smooth function: discretize(0.01) plot(f, from = 1, to = 5) 3 / 12 Continuous Random Variables Probability Density Function ST 380 Probability and Statistics for the Physical Sciences The probability that X is between two values a and b, P(a ≤ X ≤ b), can be approximated by P(a ≤ Y ≤ b). -

Binomial and Normal Distributions

Probability distributions Introduction What is a probability? If I perform n experiments and a particular event occurs on r occasions, the “relative frequency” of r this event is simply . This is an experimental observation that gives us an estimate of the n probability – there will be some random variation above and below the actual probability. If I do a large number of experiments, the relative frequency gets closer to the probability. We define the probability as meaning the limit of the relative frequency as the number of experiments tends to infinity. Usually we can calculate the probability from theoretical considerations (number of beads in a bag, number of faces of a dice, tree diagram, any other kind of statistical model). What is a random variable? A random variable (r.v.) is the value that might be obtained from some kind of experiment or measurement process in which there is some random uncertainty. A discrete r.v. takes a finite number of possible values with distinct steps between them. A continuous r.v. takes an infinite number of values which vary smoothly. We talk not of the probability of getting a particular value but of the probability that a value lies between certain limits. Random variables are given names which start with a capital letter. An r.v. is a numerical value (eg. a head is not a value but the number of heads in 10 throws is an r.v.) Eg the score when throwing a dice (discrete); the air temperature at a random time and date (continuous); the age of a cat chosen at random. -

On Median and Quartile Sets of Ordered Random Variables*

ISSN 2590-9770 The Art of Discrete and Applied Mathematics 3 (2020) #P2.08 https://doi.org/10.26493/2590-9770.1326.9fd (Also available at http://adam-journal.eu) On median and quartile sets of ordered random variables* Iztok Banicˇ Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, University of Maribor, Koroskaˇ 160, SI-2000 Maribor, Slovenia, and Institute of Mathematics, Physics and Mechanics, Jadranska 19, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia, and Andrej Marusiˇ cˇ Institute, University of Primorska, Muzejski trg 2, SI-6000 Koper, Slovenia Janez Zerovnikˇ Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, University of Ljubljana, Askerˇ cevaˇ 6, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia, and Institute of Mathematics, Physics and Mechanics, Jadranska 19, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia Received 30 November 2018, accepted 13 August 2019, published online 21 August 2020 Abstract We give new results about the set of all medians, the set of all first quartiles and the set of all third quartiles of a finite dataset. We also give new and interesting results about rela- tionships between these sets. We also use these results to provide an elementary correctness proof of the Langford’s doubling method. Keywords: Statistics, probability, median, first quartile, third quartile, median set, first quartile set, third quartile set. Math. Subj. Class. (2020): 62-07, 60E05, 60-08, 60A05, 62A01 1 Introduction Quantiles play a fundamental role in statistics: they are the critical values used in hypoth- esis testing and interval estimation. Often they are the characteristics of distributions we usually wish to estimate. The use of quantiles as primary measure of performance has *This work was supported in part by the Slovenian Research Agency (grants J1-8155, N1-0071, P2-0248, and J1-1693.) E-mail addresses: [email protected] (Iztok Banic),ˇ [email protected] (Janez Zerovnik)ˇ cb This work is licensed under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 2 Art Discrete Appl. -

Boxplots for Grouped and Clustered Data in Toxicology

Penultimate version. If citing, please refer instead to the published version in Archives of Toxicology, DOI: 10.1007/s00204-015-1608-4. Boxplots for grouped and clustered data in toxicology Philip Pallmann1, Ludwig A. Hothorn2 1 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YF, UK, Tel.: +44 (0)1524 592318, [email protected] 2 Institute of Biostatistics, Leibniz University Hannover, 30419 Hannover, Germany Abstract The vast majority of toxicological papers summarize experimental data as bar charts of means with error bars. While these graphics are easy to generate, they often obscure essen- tial features of the data, such as outliers or subgroups of individuals reacting differently to a treatment. Especially raw values are of prime importance in toxicology, therefore we argue they should not be hidden in messy supplementary tables but rather unveiled in neat graphics in the results section. We propose jittered boxplots as a very compact yet comprehensive and intuitively accessible way of visualizing grouped and clustered data from toxicological studies together with individual raw values and indications of statistical significance. A web application to create these plots is available online. Graphics, statistics, R software, body weight, micronucleus assay 1 Introduction Preparing a graphical summary is usually the first if not the most important step in a data analysis procedure, and it can be challenging especially with many-faceted datasets as they occur frequently in toxicological studies. However, even in simple experimental setups many researchers have a hard time presenting their results in a suitable manner. Browsing recent volumes of this journal, we have realized that the least favorable ways of displaying toxicological data appear to be the most popular ones (according to the number of publications that use them). -

The Upper Quartile Point: Below). the Interquartile Range (IQR)

502 Median, quartiles, and percentiles are statistical Sample Application (§) ways to summarize the location and spread of experi- Suppose the mental data. They are a robust form of data reduc- EF0-EF1 tornadoes) are: , where hundreds or thousands of data are rep- tion 1.5, 0.8, 1.4, 1.8, 8.2, 1.0, 0.7, 0.5, 1.2 resented by several summary statistics. Find the median and interquartile range. Compare First, your data from the smallest to largest sort with the mean and standard deviation. values. This is easy to do on a computer. Each data point now has a rank associated with it, such as 1st Find the Answer: (smallest value), 2nd, 3rd, ... nth (largest value). Let x Given: data set listed above. = the value of the rth Find: q r = (1/2)·(n+1)] 0.5 Mean σ is called the median, and the data value x of this middle data point is the median value (q ). Namely, 0.5 First sort the data in ascending order: q = x for n = odd 0.5 Values ( ): 0.5, 0.7, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.5, 1.8, 8.2 If n is an even number, there is no data point exactly in r): 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 the middle, so use the average of the 2 closest points: Middle: ^ q = 0.5· [x + x ] for n = even 0.5 +1 Thus, the median point is the 5th The median is a measure of the location or center data set, and corresponding value of that data point is of the data median = q = z = 1.2 km. -

Length of Stay Outlier Detection Through Cluster Analysis: a Case Study in Pediatrics Daniel Gartnera, Rema Padmanb

Length of Stay Outlier Detection through Cluster Analysis: A Case Study in Pediatrics Daniel Gartnera, Rema Padmanb aSchool of Mathematics, Cardiff University, United Kingdom bThe H. John Heinz III College, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA Abstract The increasing availability of detailed inpatient data is enabling the develop- ment of data-driven approaches to provide novel insights for the management of Length of Stay (LOS), an important quality metric in hospitals. This study examines clustering of inpatients using clinical and demographic attributes to identify LOS outliers and investigates the opportunity to reduce their LOS by comparing their order sequences with similar non-outliers in the same cluster. Learning from retrospective data on 353 pediatric inpatients admit- ted for appendectomy, we develop a two-stage procedure that first identifies a typical cluster with LOS outliers. Our second stage analysis compares orders pairwise to determine candidates for switching to make LOS outliers simi- lar to non-outliers. Results indicate that switching orders in homogeneous inpatient sub-populations within the limits of clinical guidelines may be a promising decision support strategy for LOS management. Keywords: Machine Learning; Clustering; Health Care; Length of Stay Email addresses: [email protected] (Daniel Gartner), [email protected] (Rema Padman) 1. Introduction Length of Stay (LOS) is an important quality metric in hospitals that has been studied for decades Kim and Soeken (2005); Tu et al. (1995). However, the increasing digitization of healthcare with Electronic Health Records and other clinical information systems is enabling the collection and analysis of vast amounts of data using advanced data-driven methods that may be par- ticularly valuable for LOS management Gartner (2015); Saria et al. -

Skewness and Kurtosis 2

A distribution is said to be 'skewed' when the mean and the median fall at different points in the distribution, and the balance (or centre of gravity) is shifted to one side or the other-to left or right. Measures of skewness tell us the direction and the extent of Skewness. In symmetrical distribution the mean, median and mode are identical. The more the mean moves away from the mode, the larger the asymmetry or skewness A frequency distribution is said to be symmetrical if the frequencies are equally distributed on both the sides of central value. A symmetrical distribution may be either bell – shaped or U shaped. 1- Bell – shaped or unimodel Symmetrical Distribution A symmetrical distribution is bell – shaped if the frequencies are first steadily rise and then steadily fall. There is only one mode and the values of mean, median and mode are equal. Mean = Median = Mode A frequency distribution is said to be skewed if the frequencies are not equally distributed on both the sides of the central value. A skewed distribution may be • Positively Skewed • Negatively Skewed • ‘L’ shaped positively skewed • ‘J’ shaped negatively skewed Positively skewed Mean ˃ Median ˃ Mode Negatively skewed Mean ˂ Median ˂ Mode ‘L’ Shaped Positively skewed Mean ˂ Mode Mean ˂ Median ‘J’ Shaped Negatively Skewed Mean ˃ Mode Mean ˃ Median In order to ascertain whether a distribution is skewed or not the following tests may be applied. Skewness is present if: The values of mean, median and mode do not coincide. When the data are plotted on a graph they do not give the normal bell shaped form i.e. -

Non-Parametric Vs. Parametric Tests in SAS® Venita Depuy and Paul A

NESUG 17 Analysis Perusing, Choosing, and Not Mis-using: ® Non-parametric vs. Parametric Tests in SAS Venita DePuy and Paul A. Pappas, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC ABSTRACT spread is less easy to quantify but is often represented by Most commonly used statistical procedures, such as the t- the interquartile range, which is simply the difference test, are based on the assumption of normality. The field between the first and third quartiles. of non-parametric statistics provides equivalent procedures that do not require normality, but often require DETERMINING NORMALITY assumptions such as equal variances. Parametric tests (OR LACK THEREOF) (which assume normality) are often used on non-normal One of the first steps in test selection should be data; even non-parametric tests are used when their investigating the distribution of the data. PROC assumptions are violated. This paper will provide an UNIVARIATE can be implemented to help determine overview of parametric tests and their non-parametric whether or not your data are normal. This procedure equivalents; what assumptions are required for each test; ® generates a variety of summary statistics, such as the how to perform the tests in SAS ; and guidelines for when mean and median, as well as numerical representations of both sets of assumptions are violated. properties such as skewness and kurtosis. Procedures covered will include PROCs ANOVA, CORR, If the population from which the data are obtained is NPAR1WAY, TTEST and UNIVARIATE. Discussion will normal, the mean and median should be equal or close to include assumptions and assumption violations, equal. The skewness coefficient, which is a measure of robustness, and exact versus approximate tests. -

Understanding and Comparing Distributions

Understanding and Comparing Distributions Chapter 4 Objectives: • Boxplot • Calculate Outliers • Comparing Distributions • Timeplot The Big Picture • We can answer much more interesting questions about variables when we compare distributions for different groups. • Below is a histogram of the Average Wind Speed for every day in 1989. The Big Picture (cont.) • The distribution is unimodal and skewed to the right. • The high value may be an outlier Comparing distributions can be much more interesting than just describing a single distribution. The Five-Number Summary • The five-number summary of a distribution reports its Max 8.67 median, quartiles, and Q3 2.93 extremes (maximum and minimum). Median 1.90 • Example: The five-number Q1 1.15 summary for for the daily Min 0.20 wind speed is: The Five-Number Summary • Consists of the minimum value, Q1, the median, Q3, and the maximum value, listed in that order. • Offers a reasonably complete description of the center and spread. • Calculate on the TI-83/84 using 1-Var Stats. • Used to construct the Boxplot. • Example: Five-Number Summary • 1: 20, 27, 34, 50, 86 • 2: 5, 10, 18.5, 29, 33 Daily Wind Speed: Making Boxplots • A boxplot is a graphical display of the five- number summary. • Boxplots are useful when comparing groups. • Boxplots are particularly good at pointing out outliers. Boxplot • A graph of the Five-Number Summary. • Can be drawn either horizontally or vertically. • The box represents the IQR (middle 50%) of the data. • Show less detail than histograms or stemplots, they are best used for side-by-side comparison of more than one distribution.