Transcript of Interview with Joe Edgette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn 1606-1669 REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN, born 15 July er (1608-1651), Govaert Flinck (1615-1660), and 1606 in Leiden, was the son of a miller, Harmen Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), worked during these Gerritsz. van Rijn (1568-1630), and his wife years at Van Uylenburgh's studio under Rem Neeltgen van Zuytbrouck (1568-1640). The brandt's guidance. youngest son of at least ten children, Rembrandt In 1633 Rembrandt became engaged to Van was not expected to carry on his father's business. Uylenburgh's niece Saskia (1612-1642), daughter Since the family was prosperous enough, they sent of a wealthy and prominent Frisian family. They him to the Leiden Latin School, where he remained married the following year. In 1639, at the height of for seven years. In 1620 he enrolled briefly at the his success, Rembrandt purchased a large house on University of Leiden, perhaps to study theology. the Sint-Anthonisbreestraat in Amsterdam for a Orlers, Rembrandt's first biographer, related that considerable amount of money. To acquire the because "by nature he was moved toward the art of house, however, he had to borrow heavily, creating a painting and drawing," he left the university to study debt that would eventually figure in his financial the fundamentals of painting with the Leiden artist problems of the mid-1650s. Rembrandt and Saskia Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburgh (1571 -1638). After had four children, but only Titus, born in 1641, three years with this master, Rembrandt left in 1624 survived infancy. After a long illness Saskia died in for Amsterdam, where he studied for six months 1642, the very year Rembrandt painted The Night under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the most impor Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). -

National Office Developer Receives Distinguished Performance Award

FOCUS Dr. Lawrence Buck, Michael G. O'Neill and Dr. Eric Brucker National Office Developer Receives Distinguished Performance Award Michael G. 0 ' eill , chairman of Be creati ve. Be sure that yo u are U ni ve rsity and juris doctorate from Preferred Real Estate Inves tments passionate about your wo rk, and Temple U nive rsity School of Law. (PREI), Inc., received the most impo rtantly, be yo urself. " Facul ty awards presen ted at the ban Distingui hed Perfo rmance in The PhiladeltJhia Business J ournal quet included the Di stinguished Manageme nt wa rd at the School o f ranked 0 ' eill' company the sec Graduate Teaching Award to Kenn Business Administrati o n's annual o nd largest commercial real estate Tacchino, pro fessor of taxatio n; th e scholarship banque t. This award is William Zahka Di sLin guished developer in the Philadelphia me t give n each year to individuals who Professor Award to Pe ter Oe hl ers, ropolitan area. Foll owing PREI's have made a significant contribu senio r lecturer of accounting; the success with the redevelopme nt of ti on to the wo rld of busine s. Distinguished Adjunct Teaching the Consho hocke n rive rfro nt, the Awa rd to Lawrence Colfe r, acUunct In his speech at the banque t, Mr. company has embarked o n a plan to pro fessor of ma nageme nt; and, the O 'Neill advised Widener business revitali ze the wate rfront distri ct of J o hn C. Sevi er wa rd for Dedicati o n students in attendan ce to "make Chester with a property call ed the and Service to the School of your greatnes in solving all the Wharf at Ri ve rtown. -

Geographical List of Public Sculpture-1

GEOGRAPHICAL LIST OF SELECTED PERMANENTLY DISPLAYED MAJOR WORKS BY DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH ♦ The following works have been included: Publicly accessible sculpture in parks, public gardens, squares, cemeteries Sculpture that is part of a building’s architecture, or is featured on the exterior of a building, or on the accessible grounds of a building State City Specific Location Title of Work Date CALIFORNIA San Francisco Golden Gate Park, Intersection of John F. THOMAS STARR KING, bronze statue 1888-92 Kennedy and Music Concourse Drives DC Washington Gallaudet College, Kendall Green THOMAS GALLAUDET MEMORIAL; bronze 1885-89 group DC Washington President’s Park, (“The Ellipse”), Executive *FRANCIS DAVIS MILLET AND MAJOR 1912-13 Avenue and Ellipse Drive, at northwest ARCHIBALD BUTT MEMORIAL, marble junction fountain reliefs DC Washington Dupont Circle *ADMIRAL SAMUEL FRANCIS DUPONT 1917-21 MEMORIAL (SEA, WIND and SKY), marble fountain reliefs DC Washington Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln Memorial Circle *ABRAHAM LINCOLN, marble statue 1911-22 NW DC Washington President’s Park South *FIRST DIVISION MEMORIAL (VICTORY), 1921-24 bronze statue GEORGIA Atlanta Norfolk Southern Corporation Plaza, 1200 *SAMUEL SPENCER, bronze statue 1909-10 Peachtree Street NE GEORGIA Savannah Chippewa Square GOVERNOR JAMES EDWARD 1907-10 OGLETHORPE, bronze statue ILLINOIS Chicago Garfield Park Conservatory INDIAN CORN (WOMAN AND BULL), bronze 1893? group !1 State City Specific Location Title of Work Date ILLINOIS Chicago Washington Park, 51st Street and Dr. GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, bronze 1903-04 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, equestrian replica ILLINOIS Chicago Jackson Park THE REPUBLIC, gilded bronze statue 1915-18 ILLINOIS Chicago East Erie Street Victory (First Division Memorial); bronze 1921-24 reproduction ILLINOIS Danville In front of Federal Courthouse on Vermilion DANVILLE, ILLINOIS FOUNTAIN, by Paul 1913-15 Street Manship designed by D.C. -

La Salle Magazine Summer 1974 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Magazine University Publications Summer 1974 La Salle Magazine Summer 1974 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/lasalle_magazine Recommended Citation La Salle University, "La Salle Magazine Summer 1974" (1974). La Salle Magazine. 140. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/lasalle_magazine/140 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Magazine by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUMMER 1974 JONES and CUNNINGHAM of The Newsroom A QUARTERLY LA SALLE COLLEGE MAGAZINE Volume 18 Summer, 1974 Number 3 Robert S. Lyons, Jr., ’61, Editor Joseph P. Batory, ’64, Associate Editor James J. McDonald, ’58, Alumni News ALUMNI ASSOCIATION OFFICERS John J. McNally, ’64, President Joseph M. Gindhart, Esq., ’58, Executive Vice President Julius E. Fioravanti, Esq., ’53, Vice President Ronald C. Giletti, ’62, Secretary Catherine A. Callahan, ’71, Treasurer La Salle M agazine is published quarterly by La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141, for the alumni, students, faculty and friends of the college. Editorial and business offices located at the News Bureau, La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141. Second class postage paid at Philadelphia, Penna. Changes of address should be sent at least 30 days prior to publication of the issue with which it is to take effect, to the Alumni Office, La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141. Member of the American Alumni Council and Ameri can College Public Relations Association. -

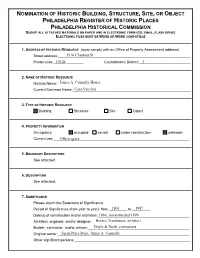

View Nomination

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3910 Chestnut St ________ Postal code:_______________19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________James A. Connelly House ________ Current/Common Name:________Casa Vecchia___________________________________________ ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________Office space ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1806 to _________1987 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1866; reconstructed 1896 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________Horace Trumbauer, architect _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________Doyle & Doak, contractors _________ Original -

Widener University Not to Discriminate on the Basis of Sex

Accredited by the Middle States Associati on of Colleges and Schools. It is the policy of Widener University not to discriminate on the basis of sex. handicap, race, age, color, religion, or national or ethnic origin in its educational programs, admissions policies, employment policies, financial aid, or other school-administered programs. This policy is enforced by federa l law under Title IX oft he Educational Amendments of 1972. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of /964, and Section 504 of the Relwbilitation Act of 1973 . Whi le correct at press time, all statements in thi s publication are subject to change without notice. Upon action of the governing body, facilities may be enlarged or otherwi se altered, courses added or deleted, and the curricula modified or expanded. Bulletin of Widener University Ser ies 1.22 • Number 6 • September 1983 (USPS #074940) Published six times a year by Widener University, once each in June. Jul y, August, and three times in September. Second class postage paid at Chester, PA 19013 . POSTMASTER: Send Fonn 3579 to: Bulletin of Widener Uni versit y, Widener Universi ty, Chester. PA 19013. ) J Bulletin of { Widener University I I 't I 1983-1984 FOR INFORMATION Widener University, Chester, PA 19013 UNIVERSITY POLICY Mr. Robert J. Bruce, President ACADEMIC POLICY Dr. Clifford T. Stewart, Provost Mr. Joseph A. Arbuckle, Assistant Provost fo r the Pennsylvania Campus Dr. Lawrence P. Buck, Dean, College of Art and Sciences Dr. Thoma G . McWill iams, Jr. , Dean, School of Engineering Dr. John T. Meli , Dean, School of Management Dr. Janette L. -

RMS Titanic - Wikipedia

RMS Titanic - Wikipedia http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Titanic RMS Titanic Da Wikipedia, l'enciclopedia libera. « Nemmeno Dio potrebbe fare affondare questa RMS Titanic nave. » (Il marinaio A.Bardetta del Titanic alla signora Caldwell, il 10 aprile 1912.) Il RMS Titanic era una nave passeggeri britannica della Olympic Class , divenuta famosa per la collisione con un iceberg nella notte tra il 14 e il 15 aprile 1912, e il conseguente drammatico affondamento avvenuto nelle prime ore del giorno successivo. Secondo di un trio di transatlantici, il Titanic , con le sue Descrizione generale due navi gemelle Olympic e Britannic , era stato progettato per offrire un collegamento settimanale con l'America, e Tipo Transatlantico garantire il dominio delle rotte oceaniche alla White Star Classe Olympic Line. Costruttori Harland and Wolff Cantiere Belfast, Irlanda del Nord. Costruito presso i cantieri Harland and Wolff di Belfast, il Titanic rappresentava la massima espressione della Impostazione 31 marzo 1909 tecnologia navale, ed era il più grande, veloce e lussuoso Completamento 31 marzo 1912 Entrata in transatlantico del mondo. Durante il suo viaggio inaugurale 10 aprile 1912 (da Southampton a New York, via Cherbourg e servizio Queenstown), entrò in collisione con un iceberg alle 23:40 Proprietario White Star Line, (ora della nave) di domenica 14 aprile 1912. L’impatto Amministratore Delegato: (Joseph Bruce Ismay) provocò l'apertura di alcune falle lungo la fiancata destra Destino finale Naufragato il 15 aprile 1912. del transatlantico, che affondò due ore e 40 minuti più tardi (alle 2:20 del 15 aprile) spezzandosi in due tronconi. Caratteristiche generali Dislocamento 52.310 t Nella sciagura, una delle più grandi tragedie nella storia Stazza lorda 46.328 t della navigazione civile, persero la vita 1517 dei 2227 Lunghezza 269 m passeggeri imbarcati. -

\.\Aes Pennsylvania PA "It,- EL~PA S- ~

LYNNEWOOD HALL HABS NO. PA-t314f3 920 Spring Avenue Elkins Park Montgomery County \.\Aes Pennsylvania PA "it,- EL~PA s- ~ PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL A.ND DESCRIPTIVE Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Department of the Intericn:· p_Q_ Box 37l2'i7 Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 I HABs Yt,r-" ... ELk'.'.PA,I HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY $- LYNNEWOOD HALL HABS No. PA-6146 Location: 920 Spring Avenue, Elkins Park, Montgomery Co., Pennsylvania. Significance: Lynnewood Hall, designed by famed Philadelphia architect Horace Trumbauer in 1898, survives as one of the finest country houses in the Philadelphia area. The 110-room mansion was built for street-car magnate P.A.B. Widener to house his growing family and art collection which would later become internationally renowned. 1 The vast scale and lavish interiors exemplify the remnants of an age when Philadelphia's self-made millionaire industrialists flourished and built their mansions in Cheltenham, apart from the Main Line's old society. Description: Lynnewood Hall is a two-story, seventeen-bay Classical Revival mansion that overlooks a terraced lawn to the south. The house is constructed of limestone and is raised one half story on a stone base that forms a terrace around the perimeter of the building. The mansion is a "T" plan with the front facade forming the cross arm of the "T". Enclosed semi circular loggias extend from the east and west ends of the cross arm and a three-story wing forms the leg of the 'T' to the north. The most imposing exterior feature is the full-height, five-bay Corinthian portico with a stone staircase and a monumental pediment. -

The Birmingham Age Herald Number 332 Volume Xnxxi Birmingham, Alabama, Tuesday’ April 23, 19.12 11 Pages

THE BIRMINGHAM AGE HERALD_ NUMBER 332 VOLUME XNXXI BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA, TUESDAY’ APRIL 23, 19.12 11 PAGES -- ... — --—-------Pi- -- ^ -■-■ ....... ■ ■ ■ n -—-- --—-* THE TITANIC SANK VICE PRESIDENT FRANKLIN ADMITS THERE WERE NOT ENOUGH UNDERWGGD TALKS BELOW WITH SUCCOR ONLY LIFE BOATS ON THE TITANIC—THEY ARE SHOWN BFPARTY’SWORKIN ' FIVE MILES AWAY, DECLARES OFFICER PLANS FOR FUTURE Fourth Officer Tells of Unidentified Steamer That Ignored Frantic Reached Birmingham Last Night to Be Present at Calls Ad- for Help—Franklin His Son’s Wedding mits Lack of Enough Boats Tomorrow Night 22.—With succor five miles Washington, April only away, THINKS the Titanic slid into its watery grave, carrying with it more DEMOCRATS ARE SURE TO WIN than 1600 of its passengers and crew, while an unidentified IN COMING ELECTION steamer that might have saved all, failed or refused to see the frantic signals flashed to it for aid. This phase of the tragic disaster was brought out today before the Senate investigation Expresses Appreciation of Alabama's committee, when ,T. B. Boxhall, fourth officer of the Titanic, Recent Action in Sending Delega- The lack of a sufficient amount of lifeboats on board Is now believed to have tion for Him to Baltimore—In told of his unsuccessful attempts to attract the stranger’s at- been responsible for the frightful loss of life when the giant Titanic plunged to / Excellent Health Except tention. the bottom. The type of lifeboat used on the vessel is also severely criticized. I for a Slight Cold This to could not have been more ship, according Boxhall, They were collapsible and Inadequately equipped for an accident of the kind I than five miles and was toward Titanic. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Philadelphia Georgian: The City House of Samuel Powel and Some of Its Eighteenth-Century Neighbors. By GEORGE B. TATUM. (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1976. xvii, 187 p. Illustrations, bibliography, index. #17.50 hard cover; #4.95 paperback.) George B. Taturn's Philadelphia Georgian is the type of comprehensive study every historic house deserves. Few American buildings are as well documented or as carefully researched as the fine brick house completed in 1766 for Charles Stedman and later owned and embellished by the "patriot mayor," Samuel Powel. Thus, the publication of this volume is a significant event. Mr. Tatum, H. Rodney Sharp Professor of Art History at the University of Delaware, places his description of the Powel House within a context of social and architectural history that underscores the importance of the building itself. While the study concentrates on the Powel House, background information is provided by a survey of Georgian architecture in America as expressed in Philadelphia and its environs. Superb photographs by Cortlandt van Dyke Hubbard illustrate the architectural heritage of the city and enable the reader to compare the Powel House with other remaining eighteenth-century buildings. Samuel Powel epitomized the colonial gentleman. Rich, well-educated, an outstanding citizen, he married Elizabeth Willing in 1769, and their house at 244 South Third Street formed the setting for the sophisticated life they led until his death in 1793. Mrs. Powel sold the house in 1798 to William Bingham; it passed through successive owners in the nineteenth century, but remained intact until 1917, when a paneled room was sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for installation in the American Wing. -

“R.M.S. Titanic” Hanson W

“R.M.S. Titanic” Hanson W. Baldwin I The White Star liner Titanic, largest ship the world had ever known, sailed from Southampton on her maiden voyage to New York on April 10, 1912. The paint on her strakes was fair and bright; she was fresh from Harland and Wolff’s Belfast yards, strong in the strength of her forty-six thousand tons of steel, bent, hammered, shaped, and riveted through the three years of her slow birth. There was little fuss and fanfare at her sailing; her sister ship, the Olympic—slightly smaller than the Titanic— had been in service for some months and to her had gone the thunder of the cheers. But the Titanic needed no whistling steamers or shouting crowds to call attention to her superlative qualities. Her bulk dwarfed the ships near her as longshoremen singled up her mooring lines and cast off the turns of heavy rope from the dock bollards. She was not only the largest ship afloat, but was believed to be the safest. Carlisle, her builder, had given her double bottoms and had divided her hull into sixteen watertight compartments, which made her, men thought, unsinkable. She had been built to be and had been described as a gigantic lifeboat. Her designers’ dreams of a triple-screw giant, a luxurious, floating hotel, which could speed to New York at twenty-three knots, had been carefully translated from blueprints and mold loft lines at the Belfast yards into a living reality. The Titanic’s sailing from Southampton, though quiet, was not wholly uneventful. -

Titanic and the People on Board: a Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking Andrea Bijan Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History Spring 2014 Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking Andrea Bijan Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bijan, Andrea, "Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking" (2014). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 27. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/27 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking By Andrea Bijan Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 4, 2014 Readers Professor Kimberly Jensen Professor David Doellinger Copyright © Andrea Bijan 2014 2 The Titanic was originally called the ship that was “unsinkable” and was considered the most luxurious liner of its time. Unfortunately on the night of April 14, 1912 the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank early the next morning, losing many lives. The loss of life made Titanic one of the worst maritime accident in history. Originally having over 2,200 passengers and crew on board only about 700 survived; most of the survivors being from the upper class.