Violations on the Part of the United States Government of Indigenous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix E High-Potential Historic Sites

APPENDIX E HIGH-POTENTIAL HISTORIC SITES National Trails System Act, SEC. 12. [16USC1251] As used in this Act: (1) The term “high-potential historic sites” means those historic sites related to the route, or sites in close proximity thereto, which provide opportunity to interpret the historic significance of the trail during the period of its major use. Criteria for consideration as high-potential sites include historic sig nificance, presence of visible historic remnants, scenic quality, and relative freedom from intrusion.. Mission Ysleta, Mission Trail Indian and Spanish architecture including El Paso, Texas carved ceiling beams called “vigas” and bell NATIONAL REGISTER tower. Era: 17th, 18th, and 19th Century Mission Ysleta was first erected in 1692. San Elizario, Mission Trail Through a series of flooding and fire, the mis El Paso, Texas sion has been rebuilt three times. Named for the NATIONAL REGISTER patron saint of the Tiguas, the mission was first Era: 17th, 18th, and 19th Century known as San Antonio de la Ysleta. The beauti ful silver bell tower was added in the 1880s. San Elizario was built first as a military pre sidio to protect the citizens of the river settle The missions of El Paso have a tremendous ments from Apache attacks in 1789. The struc history spanning three centuries. They are con ture as it stands today has interior pillars, sidered the longest, continuously occupied reli detailed in gilt, and an extraordinary painted tin gious structures within the United States and as ceiling. far as we know, the churches have never missed one day of services. -

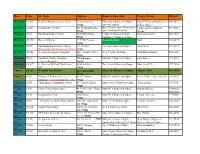

Community Service Worksheet

Place Code Site Name Address Hours of Operation Contact Person Phone # Westside CS116 Franklin Mountains State Park Transmountain Mon-Sun 8:00am to 5:00pm Robert Pichardo/Raul Gomez 566-6441 79912 MALES ONLY & Erika Rubio Westside CS127 Galatzan Rec Center 650 Wallenberg Dr. Mon - Th 1pm to 9pm; Friday 1pm to Carlos Apodaca Robert 581-5182 79912 6pm; Saturday 9am to 2pm Owens Westside CS27 Don Haskins Rec Center 7400 High Ridge Fridays 2:00pm to 6:00pm Rick Armendariz 587-1623 79912 Saturdays 9:00am to 2:00pm Westside CS140 Rescue Mission 1949 W. Paisano Residents Only Staff 532-2575 79922 Westside CS101 Environmental Services (West) 121 Atlantic Tue-Sat 8:00am to 4:00pm Jose Flores 873-8633 Martin Sandiego/Main Supervisor 472-4844 79922 Westside CS142 Westside Regional Command 4801 Osborne Drive Wed 7:00am-10:00am Orlando Hernandez 585-6088 79922 Canutillo CS111 Canutillo County Nutrition 7361 Bosque Mon-Fri 9:00am to 1:00pm Irma Torres 877-2622 (close to Westside) 79835 Canutillo CS117 St. Vincent De Paul Thrift Store 6950 3rd Street Tues-Sat 10:00am to 6:00pm Mari Cruz P. Lee 877-7030 (W) 79835 Vinton CS143 Westside Field Office 435 Vinton Rd Mon-Fri 8:00am to 6:00pm. Support Staff 886-1040 79821 Vinton CS67 Village of Vinton-(close to 436 E. Vinton Mon-Fri 8:00am to 4:00pm Perch Valdez, José Alarcón 383-6993 Anthony) avail for light duty- No 79821 Central- CS53 Chihuahuita Community Center 417 Charles Road Mon - Fri 11:00am to 6:00pm Patricia Rios 533-6909 DT 79901 Central- CS11 Civic Center Maintenance #1 Civic Center Plaza Mon-Fri 6:00am to 4:00pm Manny Molina 534-0626/ DT 79901 534-0644 Central- CS14 Opportunity Center 1208 Myrtle Mon-Fri 6:00am to 6:00p.m. -

American Indians in Texas: Conflict and Survival Phan American Indians in Texas Conflict and Survival

American Indians in Texas: Conflict and Survival Texas: American Indians in AMERICAN INDIANS IN TEXAS Conflict and Survival Phan Sandy Phan AMERICAN INDIANS IN TEXAS Conflict and Survival Sandy Phan Consultant Devia Cearlock K–12 Social Studies Specialist Amarillo Independent School District Table of Contents Publishing Credits Dona Herweck Rice, Editor-in-Chief Lee Aucoin, Creative Director American Indians in Texas ........................................... 4–5 Marcus McArthur, Ph.D., Associate Education Editor Neri Garcia, Senior Designer Stephanie Reid, Photo Editor The First People in Texas ............................................6–11 Rachelle Cracchiolo, M.S.Ed., Publisher Contact with Europeans ...........................................12–15 Image Credits Westward Expansion ................................................16–19 Cover LOC[LC–USZ62–98166] & The Granger Collection; p.1 Library of Congress; pp.2–3, 4, 5 Northwind Picture Archives; p.6 Getty Images; p.7 (top) Thinkstock; p.7 (bottom) Alamy; p.8 Photo Removal and Resistance ...........................................20–23 Researchers Inc.; p.9 (top) National Geographic Stock; p.9 (bottom) The Granger Collection; p.11 (top left) Bob Daemmrich/PhotoEdit Inc.; p.11 (top right) Calhoun County Museum; pp.12–13 The Granger Breaking Up Tribal Land ..........................................24–25 Collection; p.13 (sidebar) Library of Congress; p.14 akg-images/Newscom; p.15 Getty Images; p.16 Bridgeman Art Library; p.17 Library of Congress, (sidebar) Associated Press; p.18 Bridgeman Art Library; American Indians in Texas Today .............................26–29 p.19 The Granger Collection; p.19 (sidebar) Bridgeman Art Library; p.20 Library of Congress; p.21 Getty Images; p.22 Northwind Picture Archives; p.23 LOC [LC-USZ62–98166]; p.23 (sidebar) Nativestock Pictures; Glossary........................................................................ -

7-American Indians

AMERICAN INDIANS An interactive journey back in time, our AMERICAN INDIANS course exposes students to the American Indian culture by hands-on learning and examination through the eyes of the early explorers. During the class, students will: • “Join” Rene-Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle as the first European explorers to enter East Texas. • “Meet” woodland and plains Indians and learn how they lived before the influence of European culture. • Compare and contrast the structure of a tipi and a wigwam. • Taste samples of foods eaten by many American Indian tribes. • Learn to hunt with a bow and arrow. • Hold tools crafted with bone, stone, and sinew. • Make a bead bracelet and learn how paints were developed and used. • Experience a Pow Wow and receive an individual tribal name. • Observe a native winter count and learn how to create their own. American Indians LS LaSalle VL Villiage Life TEKS Blueprint WT Weapons Tools Readiness TEKS Student Expectation LS VL WT Supporting Identify American Indian groups in Texas and North America before European exploration such as the Readiness 4.1 B Lipan Apache, Karankawa, Caddo, and Jumano. Describe the regions in which American Indians lived and identify American Indian groups remaining in Supporting 4.1 C Texas such as the Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo, Alabama-Coushatta, and Kickapoo. Compare the ways of life of American Indian groups in Texas and North America before European Supporting 4.1 D exploration. Summarize motivations for European exploration and settlement of Texas, including economic opportunity, Readiness 4.2 A competition, and the desire for expansion. -

2019 Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo Year End Report

YSLETA DEL SUR PUEBLO 2019 YEAR-END REPORT YSLETA DEL SUR PUEBLO 2019 YEAR-END REPORT The 2019 Year-End Report highlights eight traditional recipes, each steeped in Tigua culture and history. The featured dishes range from albondigas to verdolagas and classic tigua bread—many of which are not only served in tribal homes, but also prepared for the St. Anthony’s Feast. All of the recipes hold agricultural and historical ties to Pueblo lands and people. Tigua harvests and indigenous crops, such as corn, beans, squash, chilies, and tomatoes, determined what was prepared and consumed on the Pueblo. Tigua planting cycles followed the phases of the moon. A new field, for example, would be planted four days before the new moon on the third month (i.e., March) of the new year. All of the featured recipes were contributed and prepared by Tribal members. Thank you to all those who made this project possible. THE RECIPES 2019 YEAR-END REPORT ALBONDIGAS 6 Published by Ysleta del Sur Pueblo BISCOCHOS 16 119 S. Old Pueblo Rd. Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, TX 79907 CALABASAS 26 915.859.7913 www.ysletadelsurpueblo.org CHILE COLORADO 34 RED CHILE & PEA SOUP 52 The Year-End Report is compiled under the direction of Tribal Operations. Electronic copies of the report are SOPA DE PAN 58 available on the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo website (http://www.ysletadelsurpueblo.org/) under the TIGUA BREAD 64 Tribal Council section. VERDOLAGAS 76 Printed and assembled in El Paso, Texas by Tovar Printing May 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE GOVERNOR 4 PUBLIC SAFETY 54 Tribal -

Brief of Amici Curiae National Congress of American Indians, Et

No. 19-403 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- ALABAMA-COUSHATTA TRIBE OF TEXAS, Petitioner, v. STATE OF TEXAS, Respondent. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The U.S. Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE NATIONAL CONGRESS OF AMERICAN INDIANS FUND, NATIONAL INDIAN GAMING ASSOCIATION, AND USET SOVEREIGNTY PROTECTION FUND IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR CERTIORARI --------------------------------- --------------------------------- DANIEL LEWERENZ DERRICK BEETSO Counsel of Record NCAI FUND JOEL WEST WILLIAMS 1516 P Street NW NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS FUND Washington, DC 20005 1514 P Street NW, Suite D Telephone: (202) 466-7767 Washington, DC 20005 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: (202) 785-4166 GREGORY A. SMITH E-mail: [email protected] HOBBS STRAUS DEAN & E-mail: [email protected] WALKER, LLP STEVEN J. GUNN 1899 L Street NW, 1301 Hollins Street Suite 1200 St. Louis, MO 63135 Washington, DC 20037 Telephone: (314) 920-9129 Telephone: (202) 822-8282 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: gsmith@hobbs Counsel for National straus.com Indian Gaming Association Counsel for USET SPF ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL -

The National Congress of American Indians Resolution #ABQ-10-031

N A T I O N A L C O N G R E S S O F A M E R I C A N I N D I A N S The National Congress of American Indians Resolution #ABQ-10-031 TITLE: Requesting the Federal Trustee Assist the Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo in Its Efforts to Secure Its Sovereign Right to Engage in Economic Development Including Gaming E XECUTIVE C OMMITTEE WHEREAS, we, the members of the National Congress of American Indians PRESIDENT of the United States, invoking the divine blessing of the Creator upon our efforts and Jefferson Keel Chickasaw Nation purposes, in order to preserve for ourselves and our descendants the inherent sovereign FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT rights of our Indian nations, rights secured under Indian treaties and agreements with Juana Majel Dixon Pauma Band – Mission Ind i a n s the United States, and all other rights and benefits to which we are entitled under the RECORDING SECRETARY laws and Constitution of the United States, to enlighten the public toward a better Matthew Wesaw Pokagon Band of Potawatomie understanding of the Indian people, to preserve Indian cultural values, and otherwise TREASURER promote the health, safety and welfare of the Indian people, do hereby establish and W. Ron Allen Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe submit the following resolution; and REGIONAL V ICE-PRESIDENTS ALASKA William Martin WHEREAS, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) was Central Council Tlingit & Haida established in 1944 and is the oldest and largest national organization of American EASTERN OKLAHOMA Cara Cowan Watts Indian and Alaska Native tribal governments; -

July 6, 2020 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL Roger Goodell, Commissioner

July 6, 2020 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL Roger Goodell, Commissioner National FootBall League 280 Park Avenue New York, NY 10017 [email protected] Dear Mr. Goodell, The undersigned are Native American leaders and organizations that have worked tirelessly and substantively for over half a century to change the racist name of the Washington team. We appreciate the statements made in recent days regarding the league and the team’s intention to revisit the name, But we are deeply concerned that the process or decision to rename is Being made in aBsence of any discussion with the concerned leadership. Specifically, we, the undersigned, request that the NFL immediately: 1. Require the Washington NFL team (Owner- Dan Snyder) to immediately change the name R*dsk*ns, a dictionary defined racial slur for Native Peoples. 2. Require the Washington team to immediately cease the use of racialized Native American Branding By eliminating any and all imagery of or evocative of Native American culture, traditions, and spirituality from their team franchise including the logo. This includes the use of Native terms, feathers, arrows, or monikers that assume the presence of Native American culture, as well as any characterization of any physical attributes. 3. Cease the use of the 2016 Washington Post Poll and the 2004 National AnnenBerg Election Survey which have Been repeatedly used By the franchise and supporters to rationalize the use of the racist r-word name. These surveys were not academically vetted and were called unethical and inaccurate By the Native American Journalist Association as well as deemed damaging By other prominent organizations that represent Native Peoples. -

National Trails Intermountain Region FY 2011 Superintendent's Annual

National Trails Intermountain Region FY 2011 Superintendent’s Annual Report Aaron Mahr, Superintendent P.O. Box 728 Santa Fe, New Mexico, 87504 Dedication for new wayside exhibits and highway signs for the Santa Fe National Historic Trail through Cimarron, New Mexico Contents 1 Executive Summary 2 Administration and Stafng Organization and Purpose Budgets Staf NTIR Funding for FY11 4 Core Operations Partnerships and Programs Feasibility Studies California and Oregon NHTs El Camino Real de los Tejas NHT El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro NHT Mormon Pioneer NHT Old Spanish NHT Pony Express NHT Santa Fe NHT Trail of Tears NHT 23 NTIR Trails Project Summary Challenge Cost Share Program Summary ONPS Base-funded Projects Projected Supported with Other Funding 27 Content Management System 27 Volunteer-in-Parks 28 Geographic Information System 30 Resource Advocacy and Protection 32 Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program Route 66 Cost Share Grant Program 34 Tribal Consultation 35 Summary Acronym List BEOL - Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site BLM - Bureau of Land Management CALI - California National Historic Trail CARTA - El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Association CAVO - Capulin Volcanic National Monument CCSP - Challenge Cost Share Program CESU - Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit CMP/EA - comprehensive management plan/environmental assessment CTTP - Connect Trails to Parks DOT - Department of Transportation EA - environmental assessment ELCA - El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail ELTE - El Camino -

Amicus Brief

Case: 18-40116 Document: 00514921390 Page: 1 Date Filed: 04/18/2019 No. 18-40116 In the United States Court of Appeals For the Fifth Circuit ______________________________ STATE OF TEXAS, Plaintiff – Appellee, v. ALABAMA-COUSHATTA TRIBE OF TEXAS, Defendant – Appellant On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, Lufkin Division, No. 9:01-cv-299 BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE NATIONAL CONGRESS OF AMERICAN INDIANS AND USET SOVEREIGNTY PROTECTION FUND IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTFF-APPELLANT’S PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC Daniel Lewerenz Derrick Beetso NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS FUND NATIONAL CONGRESS OF 1514 P Street NW, Suite D AMERICAN INDIANS Washington, DC 20005 1516 P Street NW Telephone: (202) 785-4166 Washington, DC 20005 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: (202) 466-7767 Counsel of record E-mail: [email protected] Gregory A. Smith HOBBS STRAUS DEAN & WALKER, LLP 2120 L Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20037 Telephone: (202) 822-8282 E-mail: [email protected] Counsel for USET SPF Case: 18-40116 Document: 00514921390 Page: 2 Date Filed: 04/18/2019 CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS State of Texas v. Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, No. 18-40116 The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following listed persons and entities as described in the fourth sentence of 5th Cir. R. 28.2.1 have an interest in the outcome of this case. These representations are made in order that the judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal. PLAINTIFF – APPELLEE: State of Texas COUNSEL FOR PLAINTIFF – APPELLEE: Ken Paxton Jeffrey C. -

Caddo Indians- Grade 4

Caddo Indians - Grade 4 Created for public use and for TIDES project partner Caddo Mounds State Historic Site by Rhonda Williams, TIDES Curriculum Development team member, 2004. Revised by Rachel Galan, Caddo Mounds State Historic Site, Educator/ Interpreter, February 2014. TEKS updated to the August 2010 revision. Objectives: TEKS §113.15. History, Grade 4. (b) (1) The student understands the origins, similarities, and differences of American Indian groups in Texas and North America before European exploration. The student is expected to: (B) identify American Indian groups in Texas and North America before European exploration such as the Lipan Apache, Karankawa, Caddo, and Jumano; (C) describe the regions in which American Indians lived and identify American Indian groups remaining in Texas such as the Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo, Alabama-Coushatta, and Kickapoo; and (D) compare the ways of life of American Indian groups in Texas and North America before European exploration. TEKS §113.15. History, Grade 4. (b)(4) The student understands the political, economic, and social changes in Texas during the last half of the 19th century. The student is expected to: (D) examine the effects upon American Indian life resulting from changes in Texas, including the Red River War, building of U.S. forts and railroads, and loss of buffalo. TEKS §113.15. Geography, Grade 4. (b)(6) The student uses geographic tools to collect, analyze, and interpret data. The student is expected to: (A) apply geographic tools, including grid systems, legends, symbols, scales, and compass roses, to construct and interpret maps (Map of Texas Forts and Indians 1846-1850); and TEKS §113.15. -

W-452 500 West University El Paso, Texas 79968 Phone 915-747-5672

Guide to Catholic-Related Records in the West about Native Americans See User Guide for help on interpreting entries TEXAS, EL PASO new 2006 C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department, University of Texas at El Paso W-452 500 West University El Paso, Texas 79968 Phone 915-747-5672 http://libraryweb.utep.edu/special/special.cfm Hours: Classes in session, Monday-Tuesday, Thursday-Friday, 8:00-5:00, Wednesday, 8:00-9:00, and Saturday, 10:00-2:00; and intersession, Monday- Tuesday, Thursday-Friday, 8:00-5:00, and Wednesday, 8:00-6:00 Access: No restrictions Copying facilities: Yes Holdings of Catholic-related records about Native Americans: Inclusive dates: 1578-1992 Volume: Approximately .7 cubic foot Description: 15 collections include Native Catholic records. Manuscript and Oral History Collections /1 “C.L. Sonnichsen Papers, Ms 141” Inclusive dates: Between 1861-1991 Volume: Few items Description: Manuscript, photographs, and research notes, re: Apache and Tiwa Indians and Reverend Decorme of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Ysleta) Mission, El Paso; finding aid online. /2 “Oral History Collection” Inclusive dates: 1970, 1977 Volume: 8 sound recordings and 1 transcript Description: a. Tiwa Indians, El Paso, Texas, 1970, 1 sound recording each: No. 102.1, Pablo Carbajal, No. 102.2, Rafael Dominguez, No. 102.3, Guadalupe Garcia, No. 102.4, Trinidad J. Granillo, No. 102.5, Ramona Natai, No. 102.6, Mike Pedraza, and No. 102.7, Pablo Silvas, re: community life and history, which is believed to include Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church b. Yaqui Indians, El Paso, Texas, 1977, 1 sound recording and transcript: No.