European Slave Trading, Abolitionism, and ‘New Systems of Slavery’ in the Indian Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

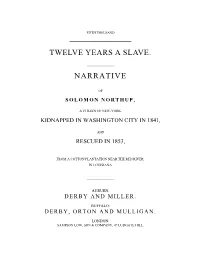

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif

“Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif. Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani To cite this version: Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani. “Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif.. Comparativ, Leipzig University, 2019, 29 (3), pp.41-64. hal-02954571 HAL Id: hal-02954571 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02954571 Submitted on 1 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo, 1890-1914. Debates about abolition of slavery have essentially focused on two interrelated questions: 1) whether nineteenth and early twentieth century abolitions were a major breakthrough compared to previous centuries (or even millennia) in the history of humankind during which bondage had been the dominant form of labour and human condition. 2) whether they express an action specific to western bourgeoisie and liberal civilization. It is true that the number of abolitionist acts and the people concerned throughout the extended nineteenth century (1780- 1914) had no equivalent in history: 30 million Russian peasants, half a million slaves in Saint- Domingue in 1790, four million slaves in the US in 1860, another million in the Caribbean (at the moment of the abolition of 1832-40), a further million in Brazil in 1885 and 250,000 in the Spanish colonies were freed during this period. -

Volume 41, 2000

BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume 41 : No. 1 Spring 2000 I I BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume 41: Numbers 1–4 2000 Original Issues Compiled by Dr. G. Roy Horst, Publisher and Managing Editor of Bat Research News, 2000. Copyright 2011 Bat Research News. All rights reserved. This material is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced, transmitted, posted on a Web site or a listserve, or disseminated in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the Publisher, Dr. Margaret A. Griffiths. The material is for individual use only. Bat Research News is ISSN # 0005-6227. BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume41 Spring 2000 Numberl Contents Resolution on Rabies Exposure Merlin Tuttle and Thomas Griffiths o o o o eo o o o • o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 o o o o o o o o o o o 0 o o o 1 E - Mail Directory - 2000 Compiled by Roy Horst •••• 0 ...................... 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••• 2 ,t:.'. Recent Literature Compiled by :Margaret Griffiths . : ....••... •"r''• ..., .... >.•••••• , ••••• • ••< ...... 19 ,.!,..j,..,' ""o: ,II ,' f 'lf.,·,,- .,'b'l: ,~··.,., lfl!t • 0'( Titles Presented at the 7th Bat Researc:b Confei'ebee~;Moscow :i'\prill4-16~ '1999,., ..,, ~ .• , ' ' • I"',.., .. ' ""!' ,. Compiled by Roy Horst .. : .......... ~ ... ~· ....... : :· ,"'·~ .• ~:• .... ; •. ,·~ •.•, .. , ........ 22 ·.t.'t, J .,•• ~~ Letters to the Editor 26 I ••• 0 ••••• 0 •••••••••••• 0 ••••••• 0. 0. 0 0 ••••••• 0 •• 0. 0 •••••••• 0 ••••••••• 30 News . " Future Meetings, Conferences and Symposium ..................... ~ ..,•'.: .. ,. ·..; .... 31 Front Cover The illustration of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum on the front cover of this issue is by Philippe Penicaud . from his very handsome series of drawings representing the bats of France. -

Women, Slavery, and British Imperial Interventions in Mauritius, 1810–1845

Women, Slavery, and British Imperial Interventions in Mauritius, 1810–1845 Tyler Yank Department of History and Classical Studies Faculty of Arts McGill University, Montréal October 2019 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Tyler Yank 2019 ` Table of Contents ! Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Résumé ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 10 History & Historiography ............................................................................................................. 15 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................... 21 Scope of Study ............................................................................................................................. -

In the Union Territory of Puducherry

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Comparative Study on the Peak Expiratory Flow Rate of School Children(10 – 14 years) in the Union Territory of Puducherry D.Savita * V. Raji Sugumar ** Abstract Peak Expiratory Flow Rate of children has been known to vary with region. The present study aimed to compare Keywords: the airway patency of school children (10 – 14 years)in School children; each of the 4 regions of the Union Territory of peak expiratory flow rate; Puducherry based on PEFR zones. A cross sectional anthropometric study was conducted among 1926 school children measurement; selected by stratified random sampling method. Union Territory of Anthropometric measurements and Peak Expiratory Flow Puducherry; Rate were assessed using .prescribed standardized tools such as stadiometer, weighing machine, non-stretchable flexi tape and Mini Wright peak flow meter. Data was analyzed using SPSS 19.0 version.The results revealed a significant difference in the anthropometric and PEFR * Ph.D. Scholar, PG & Research Department of Home Science,Bharathidasan Govt. College for Women, (Autonomous), Puducherry ** Associate Professor & Head,PG & Research Department of Home Science,Bharathidasan Govt. College for Women, (Autonomous), Puducherry 13 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 values in all the 4 regions. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

Puducherry S.No

Puducherry S.No. District Name of the Address Major Activity Broad NIC Owners Employ Code Establishment Description Activity hip ment Code Code Class Interval 1 01 REGENCY JUNIOR 218 METTAKURU EDUCATION 20 852 2 25-29 COLLEGE 533464 2 01 REGENCY PUBLIC 218 METTAKURU EDUCATION 20 852 2 30-99 SCHOOL 533464 3 01 KHADI SPINNING 033 GOPAL NAGAR, SPINNING 06 131 1 25-29 CENTRE YANAM 533464 4 01 SRI SAI SRI AGRO 1-16-016 DRAKSHA RICE MILLING 06 106 2 10-14 FOODS RAMA ROAD, 533464 5 01 JAWAHAR 01-03-013 HIGHER 20 852 1 30-99 NAVODAYA METTAKUR, YANAM. SECONDARY VIDYALAYA 533464 EDUCATION 6 01 GOVERNMENT 1-3-20 YANAM HIGH SCHOOL 20 852 1 15-19 HIGH SCHOOL 533464 EDUCATION 7 01 M/S.VADIKA INDRA METTAKURU, MANUFACTURING 06 210 2 10-14 LIMITED. YANAM. 533464 OF TABLETS 8 01 M/S. LORD 25 MAIN ROAD, MANUFACTURING 06 210 3 10-14 VENKEY PHARMA METTAKURU, OF TABLETS YANAM, 533464 9 01 VADIKA INDIA 25, MAIN ROAD, MANUFACTURING 06 210 3 10-14 METTAKURU, OF TABLETS YANAM 533464 10 01 SRI LAKSHMI 1-10-031 RICE BROKEN AND 06 106 3 30-99 GANESH MODERN METTAKURU, BROWN BOILED RICE MILL YANAM 533464 11 01 HI-TEC 1-11-004 HIGH PRECISION 06 282 3 30-99 ENGINEERING METTAKURU COMPONENTS(MET PRIVATE LIMITED. YANAM 533464 AL PARTS) 12 01 REGENCY PUBLIC SEETHAMMA PETA EDUCATION 20 852 2 30-99 SCHOOL METTAKURU, YANAM 533464 13 01 GOWTHAMI 1-12-014 AMBEDKAR EDUCATION 20 854 3 20-24 TEACHER NAGAR YANAM TRAINING 533464 INSTITUTE 14 01 D.N.R. -

Abolitionist Movement

Abolitionist Movement The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation. Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity between North and South leading up to the Civil War. The Underground Railroad c.1780 - 1862 The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals -- many whites but predominantly black -- who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year -- according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. Still, only a small percentage of escaping slaves received assistance from the Underground Railroad. An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a "society of Quakers, formed for such purposes." The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed "The Underground Railroad," after the then emerging steam railroads. -

Vol. 22 - Comoros

Marubeni Research Institute 2016/09/02 Sub -Saharan Report Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the focal regions of Global Challenge 2015. These reports are by Mr. Kenshi Tsunemine, an expatriate employee working in Johannesburg with a view across the region. Vol. 22 - Comoros June 10, 2016 It was well known that Marilyn Monroe wore Chanel No. 5 perfume when she went to bed. Did you know that Chanel No. 5’s essence (essential oils) comes from the flower called ylang-ylang, which is found in the African country of Comoros? Comoros is also where the so-called “living fossils”, a rare pre-historic species of fish called coelacanths, discovered in 1938 in South Africa after having thought to be extinct, are mostly found. So this time I would like to introduce the country of Comoros, fascinating like Marilyn Monroe and a little mysterious like the coelacanths. Table 1: Comoros Country Information The Union of the Comoros is an archipelago island nation located off the coast of East Africa east of Mozambique and northwest from Madagascar. 4 main islands make up the Comoros archipelago, Grande Comore, Moheli, Anjouan and Mayotte, with Grande Comore, Moheli, and Anjouan forming the Union of Comoros and Mayotte falling under French jurisdiction as an ‘overseas department” or region. The population of the 3 islands making up the Union of the Comoros is about 800,000, while their total land area comes to 2,236 square kilometers, about the same land size as Tokyo, which makes it quite a small country. Nominal GDP is roughly $600 million, which is second from the bottom among the 45 sub-Saharan African countries, just above Sao Tome and Principe, and its population is the 5th lowest (note 1). -

From the Mascarene Islands

58 New species of Cryptophagidae and Erotylidae (Coleoptera) from the Mascarene Islands New species of Cryptophagidae and Erotylidae (Coleoptera) from the Mascarene Islands GEORGY YU. LYUBARSKY Zoological Museum of Moscow State University, Bolshaya Nikitskaya ulica 6, 125009, Moscow, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] LYUBARSKI G.Yu. 2013. NEW SPECIES OF CRYPTOPHAGIDAE AND EROTYLIDAE (COLEOPTERA) FROM THE MASCARENE ISLANDS. – Latvijas Entomologs 52: 58-67. Abstract: А new species Micrambe reunionensis sp. nov. (Cryptophagidae) is described from the island of La Réunion. Cryptophilus integer (HEER, 1841) and Leucohimatium arundinaceum (FORSKAL, 1775) (Erotylidae) proved new for the Mascarene faunal district. Key words: Cryptophagidae, Erotylidae, Cryptophilus, Leucohimatium, Micrambe, La Réunion, Mascarene Archipelago. Mascarene Islands: natural conditions many recent extinctions. Volcanic islands with higher elevations The Mascarenes is an island group are relatively young. The most /ancient lavas in the south-western Indian Ocean, 700 from La Réunion are dated at 2.1 million km east of Madagascar. Commonly, it is years ago. La Réunion has been suitable subdivided into continental and oceanic for life since about 2–3 million years ago islands, and oceanic islands are further (Thébaud et al. 2009). La Réunion possesses divided into volcanic islands and coral one active and three extinct volcanoes. The islands. The archipelago includes three high island is dissected by huge caldera-like volcanic islands (La Réunion, Mauritius and valleys (cirques) created by heavy rainfall Rodrigues). Mauritius was the former home of erosion, with very deep gorges culminating dodo, the universal symbol of human-caused in narrow outlets to the sea. species extinction on the islands. -

A Global Overview of Protected Areas on the World Heritage List of Particular Importance for Biodiversity

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF PROTECTED AREAS ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE FOR BIODIVERSITY A contribution to the Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites Text and Tables compiled by Gemma Smith and Janina Jakubowska Maps compiled by Ian May UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK November 2000 Disclaimer: The contents of this report and associated maps do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.0 OVERVIEW......................................................................................................................................................1 2.0 ISSUES TO CONSIDER....................................................................................................................................1 3.0 WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY?..............................................................................................................................2 4.0 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................................3 5.0 CURRENT WORLD HERITAGE SITES............................................................................................................4