Early Childhood Care and Development- END of PROGRAMME EVALUATION !

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS

Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Table of Contents Foreword 3 About this report 5 Highlights in Achievements 7 Progress and Achievements 9 ....... Access to services to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV improved 9 ....... Access to services to prevent transmission of HIV in injecting drug use ....... improved 18 ....... Knowledge and attitudes improved 27 ....... Access to services for HIV care and support improved 30 Fund Management 41 ....... Programmatic and Financial Monitoring 41 ....... Financial Status and Utilisation of Funds 43 Operating Environment 44 Annexe 1: Implementing Partners expenditure and budgets 45 Annexe 2: Summary of Technical Progress Apr 2004–Mar 2007 49 Annexe 3: Achievements by Implementing Partners Round II, II(b) 50 Annexe 4: Guiding principles for the provision of humanitarian assistance 57 Acronyms and abbreviations 58 1 Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS 2 Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Foreword This report will be the last for the Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar (FHAM), covering its fourth and final year of operation (the fiscal year from April 2006 through March 2007). Created as a pooled funding mechanism in 2003 to support the United Nations Joint Programme on AIDS in Myanmar, the FHAM has demonstrated that international resources can be used to finance HIV services for people in need in an accountable and transparent manner. As this report details, progress has been made in nearly every area of HIV prevention – especially among the most at-risk groups related to sex work and drug use – and in terms of care and support, including anti-retroviral treatment. -

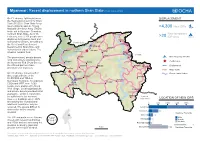

4,300 New Idps >20

Myanmar: Recent displacement in northern Shan State (as of 16 Feb 2016) On 7 February, fighting between DISPLACEMENT the Restoration Council for Shan State (RCSS) / Shan State Army South (SSA-S) and the Ta’ang >4,300 New IDPs National Liberation Army (TNLA) broke out in Kyaukme Township, northern Shan State. As of 16 Monekoe New temporary February, over 3,300 people were >20 IDP sites displaced to Kyaukme town and Konkyan surrounding villages, according to Kachin State Namhkan the Relief and Resettlement Laukkaing Mong Wee Department in Shan State and Tarmoenye humanitarian organizations. The Northern Mabein Lawt Naw Kutkai situation remains fluid. Shan State Hopang Hseni Kunlong CHINA The government, private donors, Manton Pan Lon New tempoary IDP sites local civil society organizations, Mongmit Conflict area the Myanmar Red Cross Society, Namtu the UN and partners have Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Pangwaun Displacement provided relief materials. Tawt San Major roads Mongngawt On 9 February, armed conflict Monglon Rivers / water bodies also erupted between the Hsipaw Namphan RCSS/SSA and TNLA in Kyaukme Tangyan Namhkam Township. According to Mongyai CSOs and WFP, over 1,000 Nawnghkio people were displaced to Mong Wee village. Local organisations Pangsang and private donors provided initial assistance, which is reported to be sufficient for the moment. Matman Eastern However, buildings where IDPs Shan State LOCATION OF NEW IDPS are staying are crowded and 0 500 1000 1500 2000 additional assistance may be required. The area is difficult to Kyaukme 2,400 access due to the security Kho Mone 520 situation. Kyaukme Township Mine Tin 220 The UN and partners are liaising Male closely with relevant authorities Monglon 110 Female No data and CSOs and are assessing the Pain Nal Kon 90 situation to identify gaps and provide further aid if needed. -

Important Facts About the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - Emref

Important Facts about the 2015 Myanmar General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 2015 October Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF 1 Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF ENLIGHTENED MYANMAR RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT FOUNDATION (EMReF) This report is a product of the Information Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation EMReF is an accredited non-profit research Strategies for Societies in Transition program. (EMReF has been carrying out political-oriented organization dedicated to socioeconomic and This program is supported by United States studies since 2012. In 2013, EMReF published the political studies in order to provide information Agency for International Development Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010- and evidence-based recommendations for (USAID), Microsoft, the Bill & Melinda Gates 2012). Recently, EMReF studied The Record different stakeholders. EMReF has been Foundation, and the Tableau Foundation.The Keeping and Information Sharing System of extending its role in promoting evidence-based program is housed in the University of Pyithu Hluttaw (the People’s Parliament) and policy making, enhancing political awareness Washington's Henry M. Jackson School of shared the report to all stakeholders and the and participation for citizens and CSOs through International Studies and is run in collaboration public. Currently, EMReF has been regularly providing reliable and trustworthy information with the Technology & Social Change Group collecting some important data and information on political parties and elections, parliamentary (TASCHA) in the University of Washington’s on the elections and political parties. performances, and essential development Information School, and two partner policy issues. -

Translated from the Hmannan Yazawin Dawgyl

Burmese I11vasions of Siam, Translated from the Hmannan Yazawin DawgyL ...T . Preface. 'l' he materials for the subject of this paper ·were ch awn almost entirely from the Hmn.nn a 11 Yazawin Dclwg·yi, a H istory of Burm a. in Burmese co1npil eLl by order of King Dagyict <l W of Burma i11 the ycn.r 1 101 B unnese era., A. D . 182!J . The nn t.ive work lms be en closely ac1l1erec1 to in tl1i · pnper, so nmch so that it may he co nsidered a free translat ion ( lr the original coveri 11g t he ~_J e r i o d treated of. A resume of the whole of '\vhat i · containea h re IYill lJe found in Sir A. rtlnu Phayre's llislory of Bul'lna . J n hi s l1 ist ory Sir Art hur Phayre has <Li so f ollowetl t lJ e Hmanua n Yazawin L irly closely, a nd he has utilized a1l th e in fonnat.ion IYh i.ch tl~e 1mt. ire work can offer t hat is worthy of a place in a history w rit t<~ n on European lines aml an::mgo cl it, at least tLS regards the p t·e-Alaungpric period, alm ost in the ordet· it is give n in the orig· in al. But what a, wide difference t here is between history written according to nnti ve ideas and that wr itten ou E nropoa.n principles, a. nd how far Si r Ar thur Phayre has sifted nud coudensed tl1e infon nat.ion co ntained in the original may be imagined when fi fteen pages, each containi ng t wenty eigltt lines of print in the nati1 e hist ory are wo rl.: ed into thirty one lines in Sir Arthur P ha:r re'::; . -

Shan State - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SHAN STATE - MYANMAR Mohnyin 96°40'E Sinbo 97°30'E 98°20'E 99°10'E 100°0'E 100°50'E 24°45'N 24°45'N Bhutan Dawthponeyan India China Bangladesh Myo Hla Banmauk KACHIN Vietnam Bamaw Laos Airport Bhamo Momauk Indaw Shwegu Lwegel Katha Mansi Thailand Maw Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Konkyan Cambodia 24°0'N Muse 24°0'N Muse Manhlyoe (Manhero) Konkyan Namhkan Tigyaing Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Laukkaing Mabein Tarmoenye Takaung Kutkai Chinshwehaw CHINA Mabein Kunlong Namtit Hopang Manton Kunlong Hseni Manton Hseni Hopang Pan Lon 23°15'N 23°15'N Mongmit Namtu Lashio Namtu Mongmit Pangwaun Namhsan Lashio Airport Namhsan Mongmao Mongmao Lashio Thabeikkyin Mogoke Pangwaun Monglon Mongngawt Tangyan Man Kan Kyaukme Namphan Hsipaw Singu Kyaukme Narphan Mongyai Tangyan 22°30'N 22°30'N Mongyai Pangsang Wetlet Nawnghkio Wein Nawnghkio Madaya Hsipaw Pangsang Mongpauk Mandalay CityPyinoolwin Matman Mandalay Anisakan Mongyang Chanmyathazi Ai Airport Kyethi Monghsu Sagaing Kyethi Matman Mongyang Myitnge Tada-U SHAN Monghsu Mongkhet 21°45'N MANDALAY Mongkaing Mongsan 21°45'N Sintgaing Mongkhet Mongla (Hmonesan) Mandalay Mongnawng Intaw international A Kyaukse Mongkaung Mongla Lawksawk Myittha Mongyawng Mongping Tontar Mongyu Kar Li Kunhing Kengtung Laihka Ywangan Lawksawk Kentung Laihka Kunhing Airport Mongyawng Ywangan Mongping Wundwin Kho Lam Pindaya Hopong Pinlon 21°0'N Pindaya 21°0'N Loilen Monghpyak Loilen Nansang Meiktila Taunggyi Monghpyak Thazi Kenglat Nansang Nansang Airport Heho Taunggyi Airport Ayetharyar -

The Lower Paleozoic Stratigraphy of Western Part of the Southern Shan State, Burma

Geol. Soc. Malaysia, Bulletin 6, July 1973; pp. 143-163. The Lower Paleozoic Stratigraphy of Western Part of the Southern Shan State, Burma MYINT LWIN THEINl Abstract: Rocks of all periods of the Lower Paleozoic are exposed at the western part of the Southern Shan State, typically at the Pindaya and Bawsaing (formerly known as Mawson) ranges. The Cambrian rocks are recently discovered, the Ordovician and Silurian rocks have been systematically restudied and grouped into formal lithostratigraphical units. The Cambrian (Upper), Molohein Group proposed here as a new lithostratigraphic unit, is essentially made up of clastic sediments, and composed of slightly metamorphosed mica ceous, fine-grained, pinkish to brown sandstones, and light-colored quartzites as principal rock types, and coarse-grained, pinkish sandstones, grits, greywacke, conglomerates and dolomites as minor rock types. These rocks are exposed as the cores of Pindaya Range and Hethin Hill in Bawsaing Range. The discovery of Saukiella and related genera from the mica ceous sandstones enabled the assignment of the unit as Upper Cambrian. The thickness of the group is about 3,500 feet. The lower boundary of the unit in contact with the Chaungmagyi rocks of the pre-Cambrian age (La Touche, 1913) is unconformable, while the upper bound ary in contact with the lower boundary of the Lokepyin Formation (Ordovician) is grada tional. The Ordovician rocks of the Southern Shan State can conveniently be grouped into the Pindaya Group which includes the Pindaya Beds and Mawson Series of Brown and Sondhi (1933). The Pindaya Group, herein, could be differentiated into four newly proposed forma tions, viz., (from lowest to uppermost), Lokepyin Formation (essentially containing grey siltstones), Wunbye Formation (essentially containing bedded limestones with burrowed structures and interbedded grey siltstones), Nan-on Formation (essentially containing yellow to buff color siltstones and mudstones, and Tanshauk Member (containing purplish shales and siltstones) of Nan-on Formation. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Second National Report on Unccd Implementation of the Union of Myanmar ( April 2002 )

SECOND NATIONAL REPORT ON UNCCD IMPLEMENTATION OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR ( APRIL 2002 ) Contents Page 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Background 3 3. The Strategies and Priorities Established within the Framework of 7 Sustainable Economic Development Plans 4. Institutional Measures Taken to Implement the Convention 9 5. Measures Taken or Planned to Combat Desertification 14 6. Consultative Process in Support of National Action Programme 52 with Interested Entities 7. Financial Allocation from the National Budgets 56 8. Monitoring and Evaluation 58 1. Executive Summary 1.1 The main purpose of this report is to update on the situation in Myanmar with regard to measures taken for the implementation of the UNCCD at the national level since its submission of the first national report in August 2000. 1.2 Myanmar acceded to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) in January 1997. Even before Myanmar’s accession to UNCCD, measures relating to combating desertification have been taken at the local and national levels. In 1994, the Ministry of Forestry (MOF) launched a 3-year "Greening Project for the Nine Critical Districts" of Sagaing, Magway and Mandalay Divisions in the Dry Zone. This was later extended to 13 districts with the creation of new department, the Dry Zone Greening Department (DZGD) in 1997. 1.3 The Government has stepped up its efforts on preventing land degradation and combating desertification in recent years. The most significant effort is the rural area development programme envisaged in the current Third Short-Term Five-Year Plan (2001-2002 to 2005-2006). The rural development programme has laid down 5 main activities. -

Evaluation of the Myanmar Coc Dossier and MTLAS

Evaluation of the Myanmar CoC Dossier and MTLAS By Christian Sloth and Kyaw Htun 19 February 2020 Report developed on behalf of European Timber Trade Federation Blank page 2 Contents Contents .............................................................................................................. 3 Acronyms ............................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 5 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 6 1.1 About this report........................................................................................... 6 2 Background .................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Forest governance and legality – a perspective on current situation .................... 9 2.2 Forest resources ......................................................................................... 10 2.3 Forest management and harvesting .............................................................. 14 2.3 Timber trade .............................................................................................. 20 2.4 Applicable forest laws and regulations ........................................................... 24 2.5 Timber sources in Myanmar ......................................................................... 28 2.6 Timber tracking ......................................................................................... -

China Thailand Laos

MYANMAR IDP Sites in Shan State As of 30 June 2021 BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH MYANMAR Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND CHINA List of IDP Sites In nothern Shan No. State Township IDP Site IDPs 1 Hseni Nam Sa Larp 267 2 Hsipaw Man Kaung/Naung Ti Kyar Village 120 3 Bang Yang Hka (Mung Ji Pa) 162 4 Galeng (Palaung) & Kone Khem 525 5 Galeng Zup Awng ward 5 RC 134 6 Hu Hku & Ho Hko 131 SAGAING Man Yin 7 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church) 245 Man Pying Loi Jon 8 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church-2) 155 Man Nar Pu Wan Chin Mu Lin Huong Aik 9 Mai Yu Lay New (Ta'ang) 398 Yi Hku La Shat Lum In 22 Nam Har 10 Kutkai Man Loi 84 Ngar Oe Shwe Kyaung Kone 11 Mine Yu Lay village ( Old) 264 Muse Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan 12 Mung Hawm 170 Nawng Mo Nam Kat Ho Pawt Man Hin 13 Nam Hpak Ka Mare 250 35 ☇ Konkyan 14 Nam Hpak Ka Ta'ang ( Aung Tha Pyay) 164 Chaung Wa 33 Wein Hpai Man Jat Shwe Ku Keng Kun Taw Pang Gum Nam Ngu Muse Man Mei ☇ Man Ton 15 New Pang Ku 688 Long Gam 36 Man Sum 16 Northern Pan Law 224 Thar Pyauk ☇ 34 Namhkan Lu Swe ☇ 26 Kyu Pat 12 KonkyanTar Shan Loi Mun 17 Shan Zup Aung Camp 1,084 25 Man Set Au Myar Ton Bar 18 His Aw (Chyu Fan) 830 Yae Le Man Pwe Len Lai Shauk Lu Chan Laukkaing 27 Hsi Hsar 19 Shwe Sin (Ward 3) 170 24 Tee Ma Hsin Keng Pang Mawng Hsa Ka 20 Mandung - Jinghpaw 147 Pwe Za Meik Nar Hpai Nyo Chan Yin Kyint Htin (Yan Kyin Htin) Manton Man Pu 19 Khaw Taw 21 Mandung - RC 157 Aw Kar Shwe Htu 13 Nar Lel 18 22 Muse Hpai Kawng 803 Ho Maw 14 Pang Sa Lorp Man Tet Baing Bin Nam Hum Namhkan Ho Et Man KyuLaukkaing 23 Mong Wee Shan 307 Tun Yone Kyar Ti Len Man Sat Man Nar Tun Kaw 6 Man Aw Mone Hka 10 KutkaiNam Hu 24 Nam Hkam - Nay Win Ni (Palawng) 402 Mabein Ton Kwar 23 War Sa Keng Hon Gyet Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Nawng Ae 25 Namhkan Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) 338 Si Ping Kaw Yi Man LongLaukkaing Man Kaw Ho Pang Hopong 9 16 Nar Ngu Pang Paw Long Htan (Tart Lon Htan) 26 Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) II 32 Ma Waw 11 Hko Tar Say Kaw Wein Mun 27 Nam Hkam Catholic Church ( St. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions.